Scare ’em a Little

By Robert Gordon

When Tav Falco announced his entrance on Memphis’s music scene, his caterwaul hardly seemed like the overture to a multi-decade career. In 1980, for his self-released, 4-song 7" debut, Falco silk-screened each album cover by hand and paid more attention to separating the ink colors than to separating the sounds of the instruments. He christened his band Panther Burns, after Panther Burn, Mississippi, named for the dying, frying yowls of the terrorizing beast they burned alive in a canebrake.

After decades of releases and revolving band members, Panther Burns’ sound has become more refined (if sometimes to their detriment). Falco’s punked-up rockabilly music has influenced The White Stripes, Primal Scream, The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, and many other roots and shade-tree artists.

Born in Gurdon, Arkansas, Falco pulled into Memphis in the early 1970s, leaving behind his career as a brakeman on the Missouri Pacific railroad and quickly finding the city’s bohemian edge. In Memphis, he worked as a photographer, a videographer, and a performance artist. Music became the next incarnation in his unfolding artistic development. “Here was an art form that I could participate in by just picking up the instrument—like a Kodak Instamatic camera,” Falco once told me, referring to the electric guitar at the root of his approach to music. “It was the feeling and aesthetic that mattered, more than musicianship or virtuosity. I didn’t feel hindered by my lack of conventional guitar knowledge. I just went into it full tilt.”

More than thirty years after his musical debut, he’s still tilting, far from center and ever forward. His first book, Ghosts Behind the Sun: Splendor, Enigma & Death: Mondo Memphis Volume 1, is a chronicle not only of his own peregrinations against the grain, but also of the Memphis political radicals, independent-minded artists, and occasional ax murderers who preceded and inspired him. Overall, Ghosts Behind the Sun is delightful and engaging, an innovative work. That it could have used an editor is no surprise; but if Tav Falco ever had an editor, he’d never have had a career. Someone always would have told him, “You can’t do that,” and the world would have been denied his contributions—musical, cinematic, photographic, cultural, and now literary. Like Falco’s music, parts of his book exhilarated me.

As an author, Falco’s technique is to write himself into history—he’s as present during the 1860s as he is during the 1980s. He bears a striking resemblance to Charlie Chaplin, with a touch of Errol Flynn, so it’s not hard to imagine him as from another time, a silent screen star (supported by a squalling, trance-dirge-blues soundtrack). This creative memoir begins with his 1973 arrival in Memphis atop his cherished Norton motorcycle and then shifts into his imagined experiences in the Civil War. Falco writes,

I beheld Memphis on the bluff as I would never see it again—majestic, lofty, and infused with promise, pleasure, grandeur, and every possibility and human act imaginable. . . . My gaze drifted upriver and my thoughts began to penetrate the mists 40 miles north of Memphis to the 1st Chickasaw Bluff. . . . It was during a rain and mud soaked mid-April in 1864, at not more than 16 years of age, that I joined the ranks of a Confederate Cavalry squadron 1,500 strong under the command of Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

He also gives us a first-person account of DeSoto’s sixteenth-century expedition into Tennessee; joins a posse in the late 1700s tracking America’s first serial killers, the Harpe brothers (whose demise will soon give name to Harpe’s Head Road); visits with Jim Canaan during Beale Street’s heyday under E. H. Crump; and offers gun-barrel views of several notorious murderers in action.

When Falco catches up with his own time, the Norton motorcycle (his faithful companion) shifts into high gear. He writes about his introduction to the Arkansas poet and artist Randall Lyon and Lyon’s Big Dixie Brick Company of performance artists at the University of Arkansas, and how they brought avant-garde culture to the campus.

In a farewell burst of histrionic art, we staged a Happening just a few yards off campus. . . . We further enlisted the talent of go-go dancers who had come with [the band Moloch] from Memphis. I appeared with a huge EYE painted on my chest, wearing a black top hat with a large gold hat band emblazoned with the logo that read: FUCK OFF. . . . The finale featured a blond Venus from the art department elevated on an artist model’s dais, wrapped only in a full-length mink coat, which she flamboyantly shed at the appointed moment. Chaos broke loose in the steamy room, but at the height of the frenzied ovation, a posse of city police and sheriff’s deputies came crushing through the front entrance, somehow tipped off that our so-called, and by now notorious, “mime troupe” was performing in the nude. As the fuzz came in through the front entrance, our troop managed to hightail it out the back door, down the fire escape and out into the frosty night air of Washington County—some of us never to return.

Falco’s migration to Memphis wasn’t an attempt to assimilate into the big city. Instead, he was captivated by life at the margins. Some of the nonconformists, misfits, radicals, and artists he encountered were wealthy, such as the pioneering color photographer William Eggleston, who hired Falco as his camera assistant. For Eggleston, Falco writes, “every frame was intrinsic and essential in a literary way, yet stood alone as a non-verbal abstraction of deconstructed composition and tones.” Others at the margins were dirt-farm escapees, including musicians Falco introduced to punk and post-punk audiences, like R. L. Burnside, Charlie Feathers, Cordell Jackson, and Othar Turner. What has distinguished the career of Tav Falco and his band is that they’ve seen art where others have seen trash. Theirs is the story of the late twentieth century, of rock & roll, of democratic art in action. In Ghosts, Falco continues to offer keen and celebratory insight into lesser-known artists like Randall Lyon, and like the brooding, beautiful Solip Singers, whose music was “pure gold, deep country folk blues.” Writes Falco, “Johnny Cash nor Bess Hawes nor Woody Guthrie couldn’t have touched [their] exquisite darkness.”

Several pages of the book are simply transcribed interviews with the author, and Falco’s questions elicit unique, intimate responses. Dean Phillips tells about Charlie Rich sleeping in his car in front of her house so that he could play a new song first thing in the morning for her husband, Jud, the brother of Sam Phillips. Or Roland Janes brilliantly summarizes Memphis: “Of course Los Angeles and Nashville both are highly successful, we know about their success. I think Memphis was a more loose location. The music is less inhibited, as are the musicians. I think that’s the basic difference. I think Nashville and Hollywood are more business-as-usual. In Memphis, you never know what to expect.”

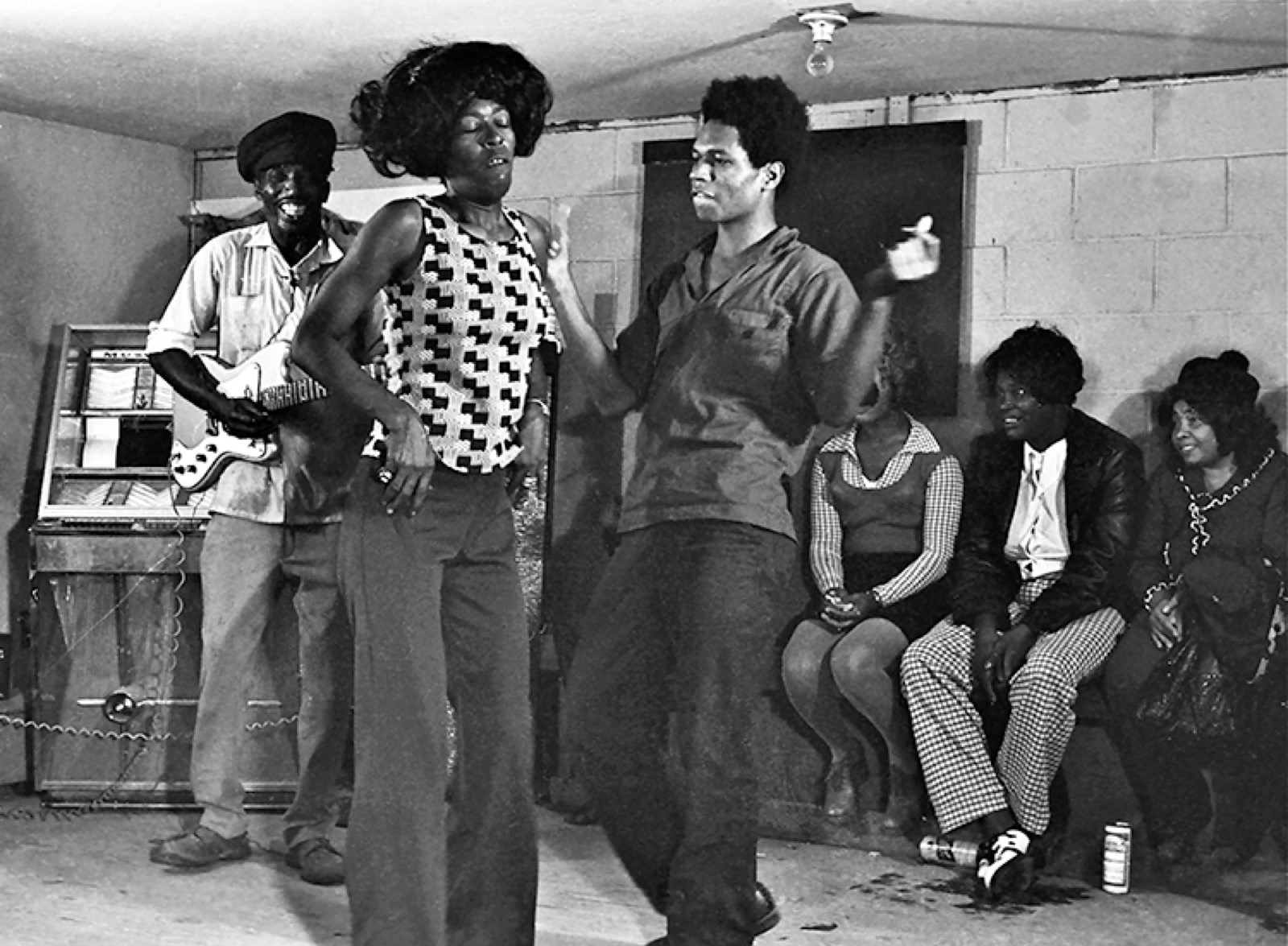

Falco’s transformation from documentarian into musician occurred in the early 1970s while videotaping R. L. Burnside at his honky tonk in the backwoods of Mississippi’s Panola County. In Ghosts, he writes that he “fell then completely under the spell of [Burnside’s] snaking, swamp infested rhythms . . . these darkly melodious strains of erotic yearning and torment that seemed to flow effortlessly from his body and from his battered, de-tuned electric guitar.” The honky tonk itself was “like a secular church,” the scene of “serious merrymaking . . . [where] the tenant farmers and tractor drivers came for the camaraderie, for the chicken frying all night in an iron skillet, for the endless cases of cold Schlitz, and they came from miles around to wager on the vagaries of the tumbling dice shaking in a leather dice horn, and for the girls working the back room.” Subsumed by what he was documenting, Falco began to lose the distinction between the observer and the observed. He found himself in front of the camera instead of behind it, and he found the six-stringed instrument of the devil.

A guy steps out on that stage and does his thing despite all the reasons he shouldn’t. Sometimes that’s when we, as an audience, feel the deepest empathy—when we’re exposed to raw and untutored expression. Falco’s art, whatever the medium, penetrates deeply because it comes from a place of honesty and conviction, rather than a preoccupation with technical skill. Charlie Feathers told him a secret about performing that Falco still uses today: “Now you gotta scare ‘em a little,” Feathers said. “You know, the audience, you gotta scare ‘em just a little.” Perhaps Falco occasionally goes too far; I’ve seen him empty a room full of diehard fans. His motto has always been the same: “You compose ‘em, we decompose ‘em.”

Early in their career, Falco and his band performed for a Memphis morning TV talk show. This was during their noisier days, and the band included a rudimentary synthesizer, a trumpeter, and Alex Chilton on guitar (with a mischievous grin). At the end of the first song—Johnny Burnette’s “Train Kept a-Rollin’”—the hostess said, “That may be the worst sound I’ve ever heard come out on television.” Complimented, Falco steered the discussion to what he saw as Panther Burns’ role within the historical context of Memphis performers, explaining, “[As a society] we can’t see what’s around us. There are blues people here who don’t have exposure, rockabilly artists who don’t have any exposure. They don’t really exist here, they’re part of our environment, we see them every day, yet they’re invisible to us. We take them for granted. It takes a group like us to create contrast, to create focus.” Ghosts Behind The Sun makes visible those heroes whom the shadows have absorbed.

All photographs by Tav Falco

William Eggleston’s legs, 1977

R. L. Burnside on guitar at the Brotherhood Sportsman’s Lodge, near Como, Mississippi, 1974

Lillian entertaining one of her admirers, Memphis, 1976

Charlie Feathers on a 1934 Harley-Davidson VLD

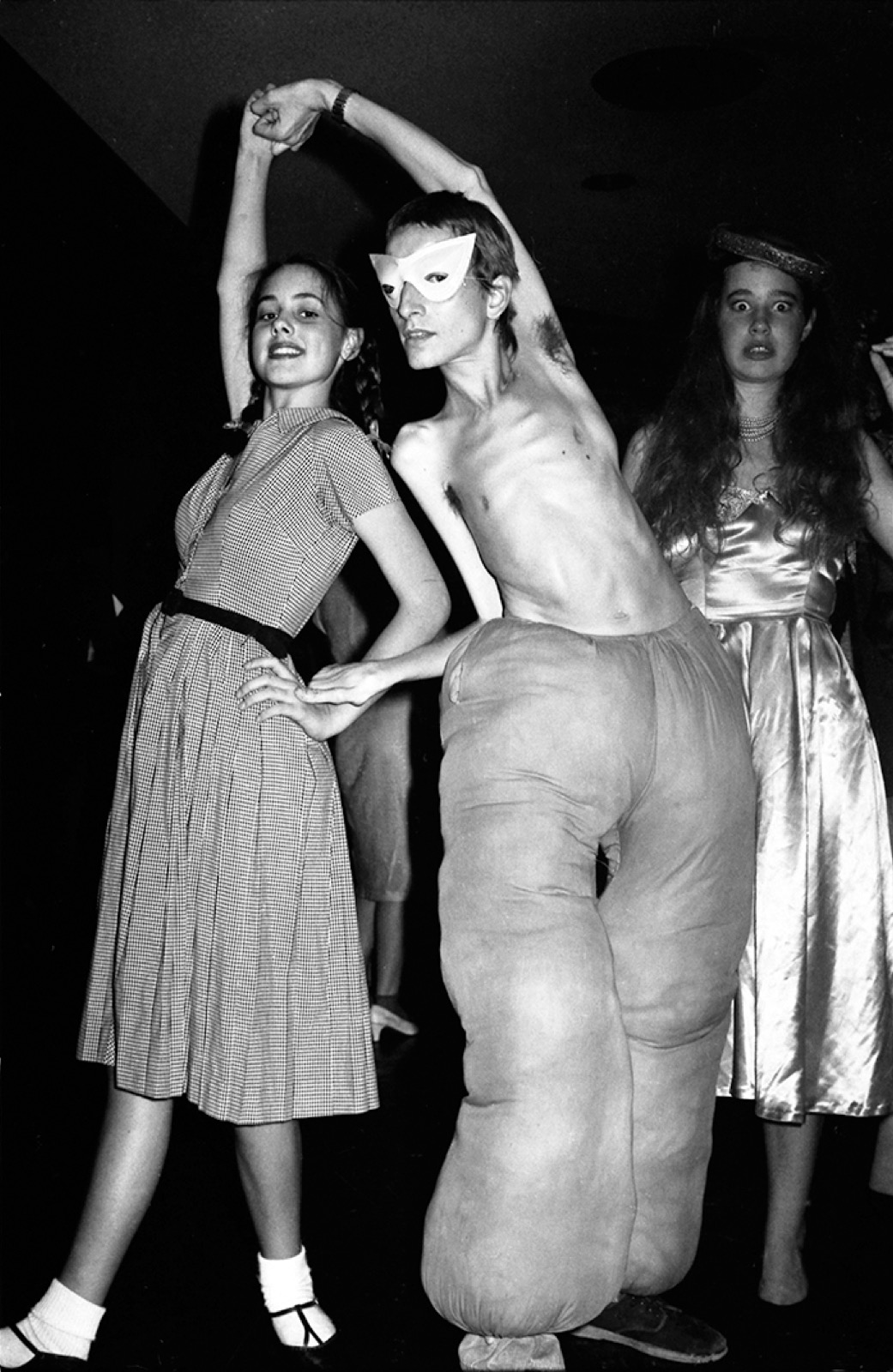

Cyd Fenwick with Rick Ivy at the Memphis Academy of Art’s masked ball, ca. 1980

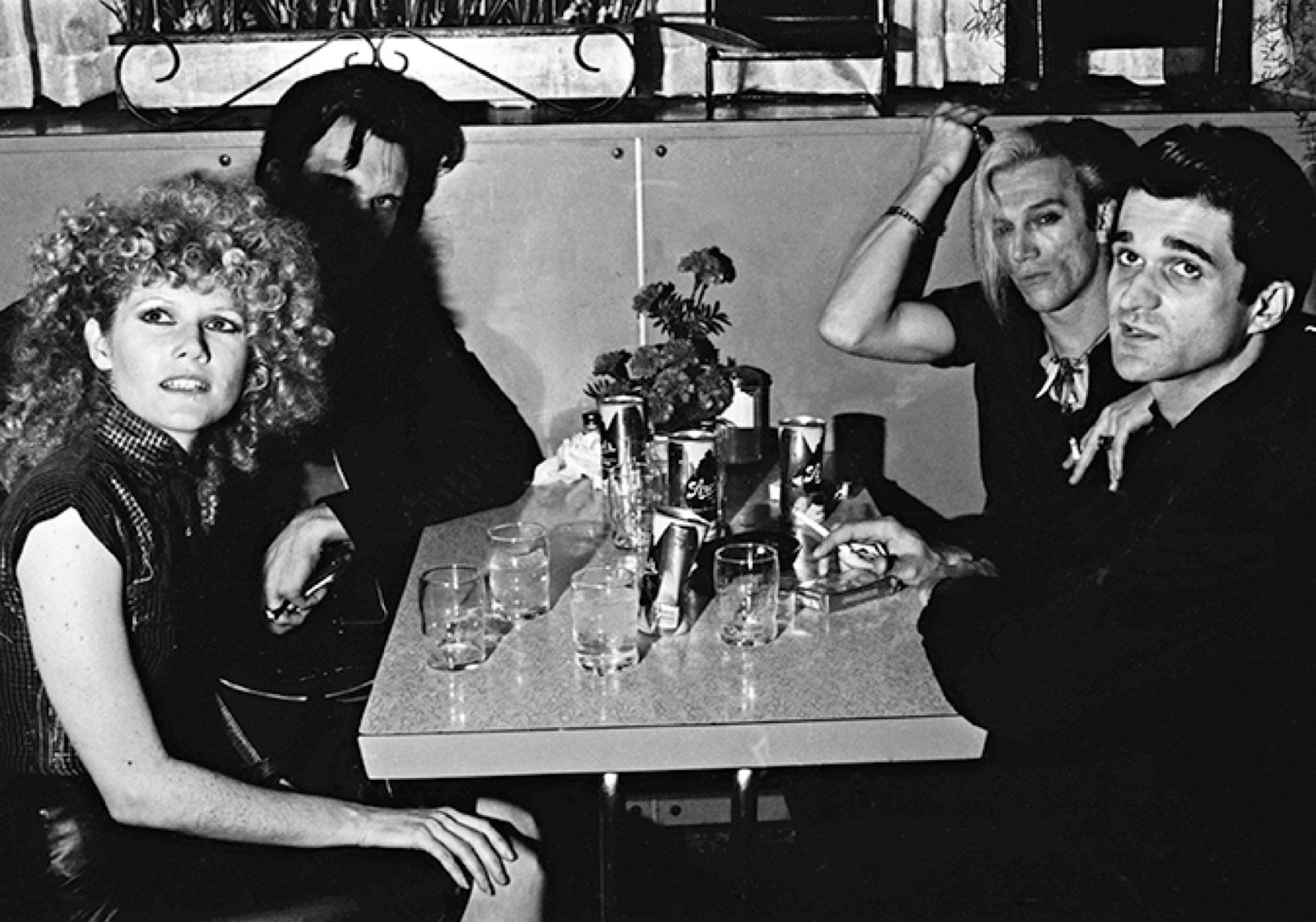

The Cramps at the Arcade Restaurant, Memphis, 1980

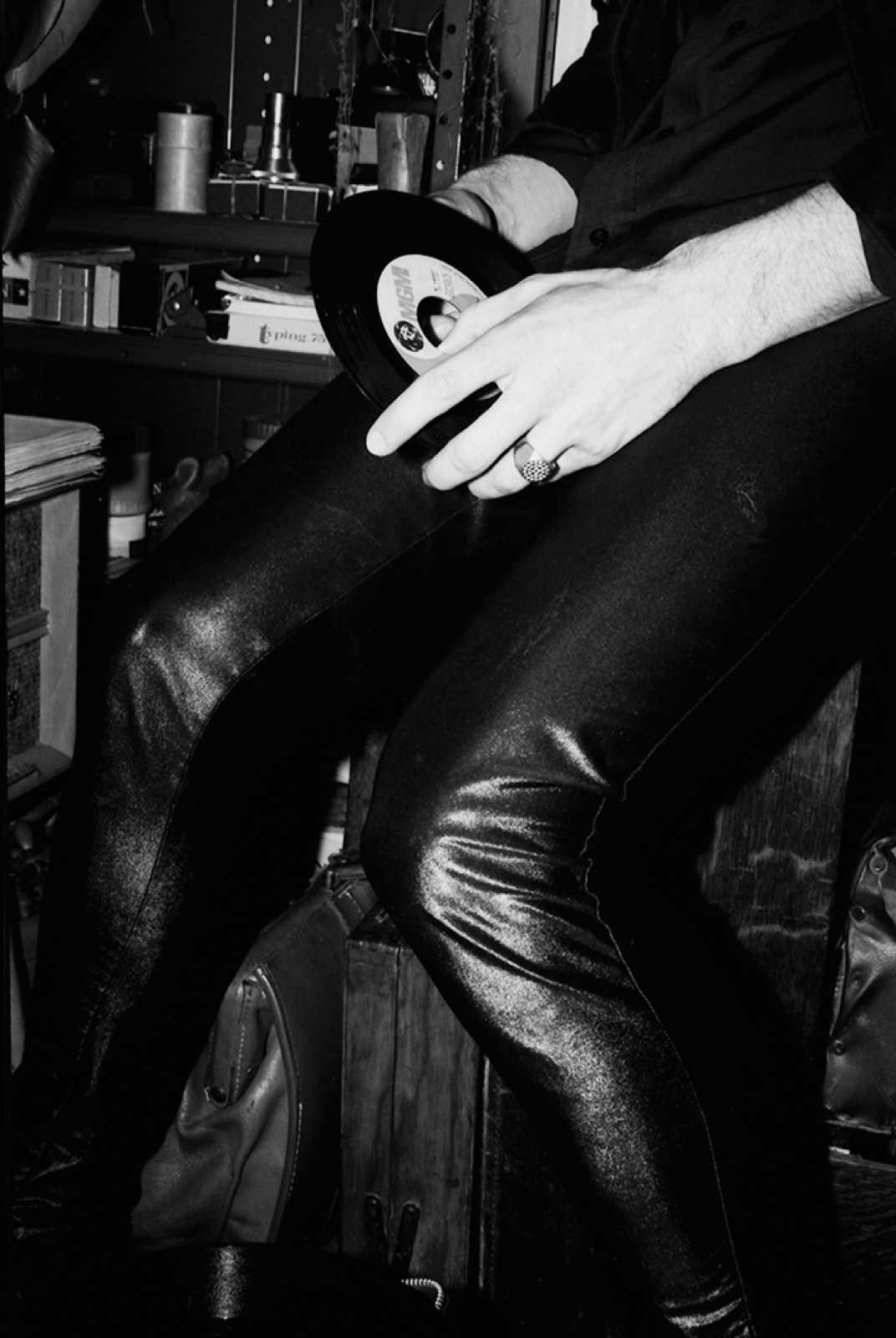

Lux Interior’s ring, 1980

Politician, Memphis, 1976