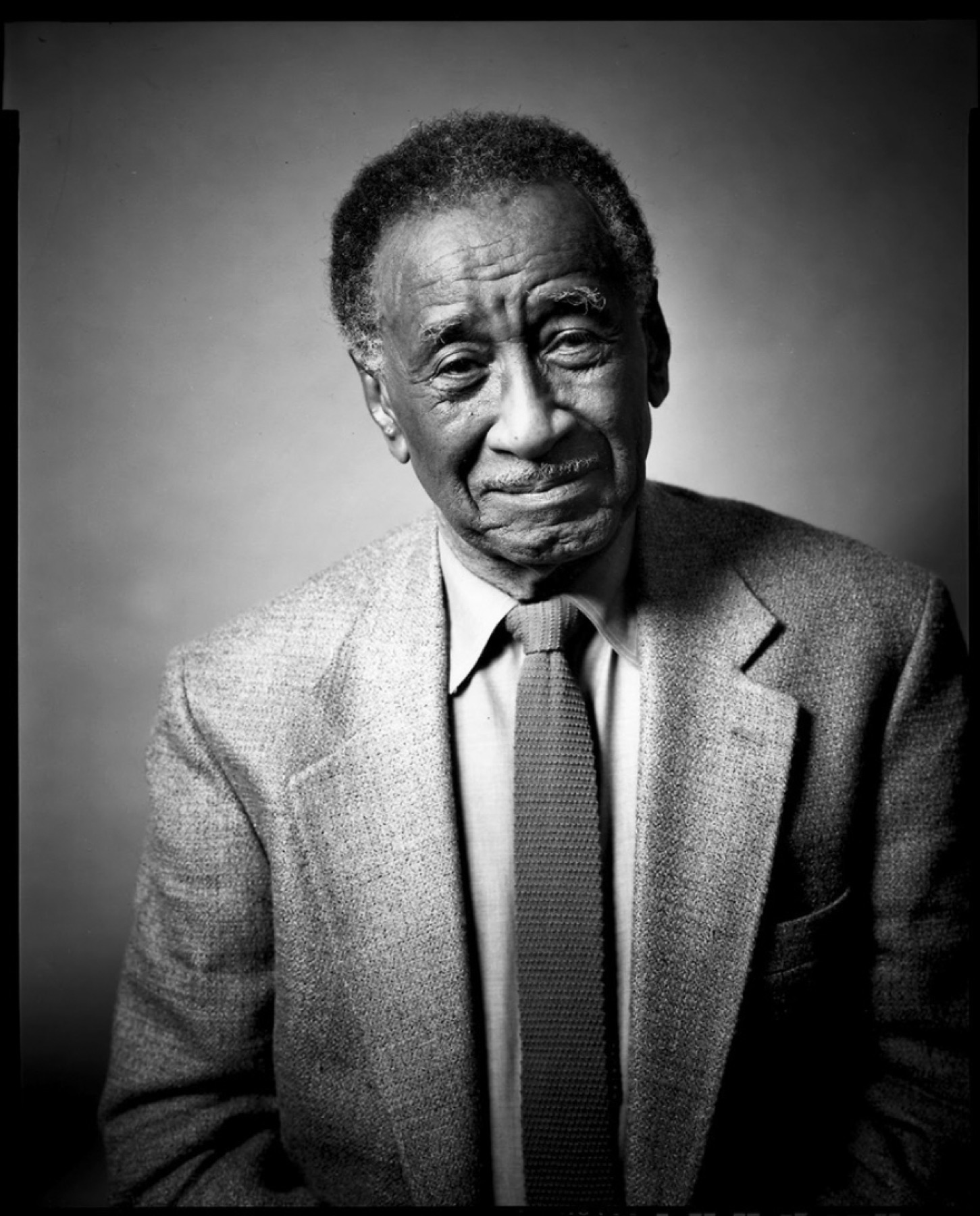

Albert Murray. Photo by Walter Beckham

The Blues Hero in the Spyglass Tree

By Walton Muyumba

Experiencing Albert Murray through his books means accepting the dare of his prose: Read these pages out loud, Basie-swinging from sentence to sentence. Murray’s literary musicality emanates from his fluency in modernist techniques and his blues idiom intelligence. All four of Murray’s novels,The Magic Keys (2005), The Seven League Boots (1996), The Spyglass Tree (1992), and Train Whistle Guitar (1974), deliver his signature high-Southern diction, gumbo-thick. Murray’s recipe takes large chunks of Papa Jo Jones hi-hat cymbal riding and Walter Page ostinato, the flour and fat simmered into a thick roux; an Ellington-Strayhorn arrangement of okra, crab meat, and shrimp for the elegant, sustained ballast; diced, minced, crushed, and ground portions of William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Thomas Mann, Wallace Stevens, Andre Malraux, and Ernest Hemingway for texture and complexity; and heavy doses of also, also, and also, Murray’s personally stylized, Mobile briarpatch seasoning. Call it “Luzana Cholly,” after the gun-toting guitar player in Train Whistle Guitar. Though all his novels are properly mixed, Murray’s cooking is especially succulent in his first:

There was a chinaberry tree in the front yard of that house in those days, and in early spring the showers outside that window always used to become pale green again. Then before long there would be chinaberry blossoms. Then it would be maytime and then junebugtime and no more school bell mornings until next September, and when you came out onto the front porch and it was fair there were chinaberry shadows on the swing and the rocking chair, and chinaberry shade all the way from the steps to the gate.When you climbed up to the best place in the chinaberry tree and looked out across Gins Alley during that time of the year the kite pasture, through which you took the short cut to the post office, would be a meadow of dog fennels again. So there would be jimson weeds as well as ragworts and rabbit tobacco along the curving roadside from the sweet gum corner to the pump shed, and pokesalad from there to the AT&N.

Here, in Train Whistle’s opening, “chinaberry” initiates Murray’s lyrical riffing, which extends through a series of echoes and variations of the word—chinaberry tree, chinaberry blossoms, maytime, junebugtime, chinaberry shadows, chinaberry shade—creating a paragraph that reads like both a modernist lyric stanza and an improvised remembrance of springtime growth. Notice how “chinaberry tree” in the second paragraph signals the narrator’s cartographic and botanical knowledge as the section unfolds. The narrator/protagonist, Scooter, maps his surroundings using the indigenous flora (dog fennel, jimson weed, ragwort, rabbit tobacco, sweet gum, and pokesalad) as landmarks, thereby placing the reader geographically and creating a kind of Southern blues pastoral.

This opening is the perfect introduction to Scooter, Murray’s hero (and avatar) from the fictional town of Gasoline Point, Alabama, whose education and maturation drives all four of Murray’s novels. In the many interviews collected in Conversations with Albert Murray, the author describes how blues idiom sensibilities influence both his literary fiction and cultural criticism. Explaining Train Whistle’s construction to Marvin Gelfand, Murray says, “The contemporary literary mind is very subtle and I play in Train Whistle Guitar with the fabulous, with fairytale, memoir, set-piece oration, sermons, shouts. Blues idiom is a context—a framework within which I’m trying to define contemporary heroism. . . . The blues—if we understand them—can help create an American free and improvisatory life style.”

In both his novels and criticism, Murray always begins in the African-American context and its traditions—the enduring types and styles in speech and movement, the narrative arts, visual artistic expression, dance, and musical performance that he calls the blues idiom. In The Hero and the Blues(1973), Murray argues that these common forms of expression have “survived from situation to situation from generation to generation” because Negroes, as he calls them lovingly, have created and refined new ways of expressing the human condition within a racist social arrangement without surrendering their own culture’s traditional practices.

Murray established his literary credentials before Train Whistle with salient critical essays on American politics and literature and African-American aesthetic ingenuity. After retiring from long careers in the Air Force (1943–1962) and teaching at Tuskegee (1940–1951), he moved to New York City in 1962, at the moment when black nationalist rhetoric was emerging as the new vehicle for black self-determination. Murray set himself apart from many black intellectuals by arguing against the exclusive, totalizing theories of black nationalism, claiming that the composite nature of everyday black experiences and black culture, as shown by the blues idiom, exemplified the American democratic ideal. Furthermore, in his cultural criticism,Stomping the Blues (1976), South to a Very Old Place (1971), and The Omni-Americans: Black Experience & American Culture (1970), Murray refutes the notion of the South as an inherently broken place, pointing to Southern African-American experience as the fount for lasting black American modes of self-identification and artistic expression.

The Omni-Americans, an especially pugnacious work, takes on all comers, including “the liberal intellectual” who “insists most urgently on being accepted as the U.S. Negro’s very best yes-white friend and sometimes even comes begging forgiveness for the slave trade, which his peasant ancestors (well, they may have been seamen) had very little to do with indeed.” Murray writes, “It is hard to say whether all this goes to show that he has no sense of humor and irony at all, or that he has far too much.” Challenging liberals and nationalists alike for their rigid, confining readings of African-American life and art, Murray argues for a more flexible, encompassing interpretation, one he structures musically:

Art is by definition a process of stylization; and what it stylizes is experience. What it objectifies, embodies, abstracts, expresses, and symbolizes is a sense of life. Accordingly, what is represented in the music, dance, painting, sculpture, literature, and architecture of a given group of people in a particular time, place, and circumstance is a conception of the essential nature and purpose of human existence itself. More specifically, an art style is the assimilation in terms of which a given community, folk, or communion of faith embodies its basic attitudes toward existence.

Murray uses strings of nouns and transitive verbs to illustrate his point, dangling, initially, a single note about art and style, then inching it progressively through an increasingly complex melody, building chordal connotations about all art practices, and he resolves it, finally, with a figure based on the opening note—a folk group’s singular aesthetic style communicates its collective philosophy.

Barbara Baker, a professor at Auburn University and a Murray scholar, claims that Murray’s special significance is that his novels and expert critiques of American aesthetics have been reviewed “through the lens of his Alabama upbringing,” with attention given to what Murray calls “the vernacular imperative,” the artist’s responsibility to convey the idioms of a particular culture while simultaneously “[stylizing] experience within artistic traditions,” revealing the universality of the local metaphor. Baker writes in the introduction of Albert Murray and the Aesthetic Imagination of a Nation that Scooter sits at the center of “Cosmos Murray”—Murray’s own term for his aesthetic philosophy—and functions within two of the author’s other key concepts: “the representative anecdote,” an example of heroic engagement with the common obstacles of human experience, and “antagonistic cooperation,” the necessary, consistent confrontation with unexpected threats and aggravations that generate the necessity for heroic action, which comes through acknowledging that “life is a lowdown dirty shame,” but that suffering can be overcome by “improvising . . . on the exigencies of the predicament.” In form and narrative Murray’s novels argue that blues idiom improvisation is heroic symbolic action in both fiction and real American life.

Although only a single, brief piece by Murray appears in Baker’s collection, his vocal intonations and pronouncements echo throughout the book. Henry Louis Gates Jr. remembers the “independence and ferocity of his voice,” and Carol Friedman claims few things are as seductive as Murray’s presence, with his “rollicking oratory [and] idiosyncratic rasp that places you squarely in the time and place of wherever [his story] lands.” Greg Thomas, a jazz critic and journalist, writes of his informal musicological and intellectual education with Murray and recalls “the Professor” ribbing him occasionally for his black nationalist leanings—such as the time Thomas visited wearing a jacket with an African print: “Man, don’t you know that when Nelson Mandela comes to the United States, he wears a Western suit?” and “I’m the one who got Stanley Crouch out of his dashiki!” and “Don’t you know that we follow Greenwich Mean Time?”

Gates, in “The King of Cats,” refers to Murray as our “most outrageous theorist of American culture,” because his interrogation of American culture and African-American experience challenges all the status quo claims about our cultural products and racial history. Murray’s primary critical assertion, which he shared with his friend and intellectual sparring partner Ralph Ellison, is that black Americans are the truest Americans. In The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement (1996), for example, Murray includes Frederick Douglass along with Emerson and Hawthorne as quintessential American voices. But he writes that it is Douglass who offers “nothing less than an unsurpassed representative anecdote (or epic or basic metaphor) of the American ideal of self-realization through the resistance to tyranny.” Gates writes that Murray understands integration as “an act of introjection” rather than accommodation, thus giving us another way of reading Murray’s works: his books reveal not only the course of his intellectual development and literary acumen, but his oeuvre’s protagonists introject the American political ideal and blues idiom attitudes as a heroic artistic/intellectual act.

Roberta Maguire explores the ways in which Murray’s close study of John Dewey’s Art as Experience helped him develop the notion that playful experimentation, within the guidelines of accepted truths about artistic genres, forms, or principles, leads to the formation of individual style. By reading Murray as a pragmatist, Maguire connects Murray’s favored rhetorical devices in fiction—representative confrontation, improvisation, and existential affirmation—with Kenneth Burke’s argument in “Literature as Equipment for Living.” For Murray, she argues, the blues idiom—its shouts, gospels, laments, and affirmations—is pragmatic, strategic, and fundamental equipment for living. Murray’s ideas beg responses from readers; we ought to argue with his works just as jazz musicians “trade twelves” in performances. “The Soloist: Albert Murray’s Blues People” is the best piece inConversations with Albert Murray. Written by the late Joe Wood, this profile both embraces and argues with Murray’s ideas. In Wood’s copy of The Blue Devils of Nada, Murray wrote, “For Joe Wood. Who plays his own riffs on this stuff.”

There are several ways to get to Harlem, as Duke Ellington once told Billy Strayhorn. But the best way isn’t always the A train express from Columbus Circle to 125th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, where the stop’s exit puts you in west Harlem facing the Manhattanville post office and a Popeye’s Chicken & Biscuits. Sometimes, if you’re coming from downtown Manhattan in need of the M60 bus to LaGuardia, or if you need to run up to Maysles Cinema to take in a new indie documentary (or had you wanted to have a few more bourbons—straight, no chasers—at Lenox Lounge before its doors were shuttered due to gentrification), the best way to Harlem on public transportation is the 2/3 express into central Harlem, one-two-five and Lenox Avenue.

When I’m in Harlem, I prefer walking. When I was living at 115th and Manhattanville Avenue, I’d walk east on 116th Street, passing the colorful West African immigrant-owned shops and cafés along the way to Lenox Avenue (which, as Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts tells us in Harlem is Nowhere, we ought to call Malcolm X Boulevard), where I’d turn left and head north twenty blocks to do research and write at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Traveling up Lenox’s wide sidewalks I would take in Harlem’s longtime demographic, its African descendants from all parts of the world. Then and now they were woven through, collage-like, with gentrifiers and tourists, Asians and Anglos, newly arrived immigrants, and African Americans who’d returned after long exiles in the outer boroughs and other states. Around 130th Street, with the Lenox Terrace apartment buildings across the street to my right and the brown brick façade of the Schomburg Center five blocks straight ahead, I think, “This is the Afroeurasian eclipse, this is Omni-America.”

Although Murray was raised in Mobile, Alabama, and lived in Tuskegee for many years, it was in Harlem, on Lenox Avenue, in Lenox Terrace, that he prepared, pounded out, polished, and published his novels and critical works. From the south-facing window in his study—in an interview, “The Unsquarest Person Duke Ellington Ever Met,” Murray calls the room his “spyglass tree”—he could take in a panoramic view of Manhattan’s midtown, with sightlines toward the wide terrain of his reimagined South.

The background image for the title pages of Baker’s Albert Murray is a black-and-white photograph of Lenox Avenue, specifically the segment between 132nd and 133rd streets. It shows west Harlem bracketed by the apartment towers of the Lionel Hampton Houses to the left and City College’s white-framed science building to the right. The photograph, taken by Carole Friedman, from Murray’s apartment balcony, captures Lenox Avenue’s mix of commercial and residential buildings, and the sky’s openness as it spreads above the narrow rows of houses squatting in formation along the numbered streets that roll slightly uphill to St. Nicholas Avenue until they hit St. Nicholas Park.

The buildings at the center of Friedman’s photograph are quite famous. In 1971 the artist Romare Bearden used them as inspiration for his majestic, six-panel painting, The Block. Bearden and Murray were close friends and coconspirators: Murray often served as Bearden’s personal art critic, writing exhibition guides for his shows, ghostwriting a few of Bearden’s essays, and even naming some of the artist’s pieces. Murray saw the visual equivalent of his literary theories in Bearden’s work. Bearden, like Murray, used his knowledge of local idiomatic traditions—“regional particulars”—in combination with his personal aesthetics to hone his individual, idiosyncratic interpretation of omni-humanity.

You can watch Murray and Bearden discuss The Block’s creation in the film Bearden Plays Bearden, which Nelson E. Breen shot in the late 1970s, when the two men were in their sixties and in their prime. In the film, the camera follows Bearden’s glance west across Lenox Avenue and cuts back to his hands as they quickly sketch with black marker the basic geometric shapes of this vista. At the end of “The Visual Equivalent to Blues Composition,” Murray uses the example of African-American jazz musicians to explain how Bearden’s collages express a signature improvisational style: “When the blues-oriented listener hears only a few bars of music on the radio or a phonograph and says Ole Louis or says Ole Duke or says Ole Count or says That’s Yardbird or That’s Monk or That’s Miles or says I hear you Trane or I hear you Ornette, he has said it all.” This kind of aural identification, as Murray understands it, is a “sophisticated awareness of art as a playful process of stylization,” and can be applied to visual art. Some art viewers can recognize a Picasso or a Motherwell on sight, and Bearden’s works—with his African mask cutouts, his black construction paper silhouettes, the colorful, mixed-media arrangements on canvas—also possess the distinct, recognizable style of a master. In the same way that one might identify “the essence of the musical statement not by subject matter and title but by how it is played,” one can identify Bearden’s works by how they are painted.

In “Albert Murray and Visual Art,” Paul Devlin does a good job of explaining how the spontaneous quality of Bearden’s collages and the visual regional detail in Murray’s fiction and criticism come from the men’s shared aesthetic sensibility, which he calls “downhome pragmatic romanticism.” Neither artist fetishized black folklife or believed in an artistic “golden age”; rather, they found that pragmatic experimentation allowed them to choose the most useful elements of the traditions they’d inherited—African, Negro-American, European, and Anglo-American—and stylize them in their own voices.

Devlin, like many other younger writers, spent years sitting at Murray’s knee in Harlem gaining a blues idiom education. One of the fruits of Murray’s tutelage is Rifftide: The Life and Opinions of Papa Jo Jones, Devlin’s edited transcription of Murray’s recorded conversations with Jo Jones, the master jazz drummer and heart of the Count Basie Orchestra’s rhythm section. From 1977 until 1985, Murray and Jones discussed the drummer’s life in jazz, especially his time in Count Basie’s orchestra. Initially these conversations were part of Murray’s research for Good Morning Blues, the as-told-to autobiography he compiled for Count Basie. In 2005, at Murray’s request, Devlin began turning these taped conversations into a book.

Devlin produced eighty-three pages of text from Murray’s tapes. His preface and introduction explain the book’s production and offer a useful biography of Jones to give some context to the musician’s narration. The book contains a section of exceptional snapshots presenting Jones, a dark-skinned, dapper man with a regal bearing, making his way through jazz history. There’s Jones playing behind Ethel Waters or alongside Teddy Wilson and Lester Young. There he is with Hank Jones and Art Blakey and Albert Murray. But don’t let Jones’s philosophical mien or cherubic smile fool you—his voice darts and bops as snappishly as his drumming. In a 1955 letter to Ralph Ellison, Murray writes about a young white drummer’s halting attempt to emulate Jones’s style, and parodies Jones, who had stood by disabusing the neophyte: “‘What you mad about? It’s music, man, music, music. From here man, here, here, here. It’s heart and soul, pardner. Man, you’re distorting the hell out of me.’ Man, that cat didn’t use nothing but brushes the rest of the night.”

Jones’s narrative concludes with him explaining that the Count Basie musicians’ familial, moral, and ethical connections—their willingness to fight for each other—inspired them to play and swing hard for audiences. Describing his own passion for the band, he says, “See there’s two things that can bring violence out of me: my wife and Count Basie. Your ass could be walkin’, ridin’, fartin’, shootin’, or shittin’. When I get out of the hospital, I’ll find ya, I’ll kill ya! Don’t fuck with my wife and don’t fuck with Count Basie. Got it? Every manager that come along says if you can get on the good side of the drummer, you’re all right.”

In Rifftide’s afterword, the jazz historian Phil Schaap writes that beginning in the late 1960s, Jones wanted to produce an autobiography but couldn’t find a suitable partner for the venture. It’s strange to think of Jones struggling to find a collaborator, since he and Murray had known each other for several decades by then. Jones shows up in Murray’s novels The Seven League Boots and The Magic Keys as the character Joe States, a drummer who trains Scooter to perform as a top-shelf bass man and touring musician in the Bossman’s orchestra. States encourages Scooter to pursue a graduate degree to complement his worldly education in jazz—but more importantly, he teaches Scooter how to improvise and survive as an American black man. Schaap, describing his lifelong friendship with the drummer and Jones’s avuncular affection, proudly claims to have earned his jazz studies degree from “Jonathan David Samuel Jones University.”

With Rifftide, Murray, Devlin, Jones, and Schaap have given us a wonderful resource for charting an underexplored section of the cultural map, for broadening our sense of how blues idiom music and attitudes have moved from down-home, up south to Harlem, and back again. But flickering behind Rifftide is a shadow book about Murray. Today Murray is ninety-seven years old; he’s infirm and bedridden, but alive. He deserves a serious critical biography, like Lawrence Jackson’s Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius or Keith Gilyard’s John Oliver Killens: A Life of Black Literary Activism. I’m hoping that Devlin, with his access to Murray’s papers and his deep understanding of the author’s intellectual history and aesthetic development, has already begun preparing for such a work—the Omni-American, gumbo-rich, blues biography of Albert Murray.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.