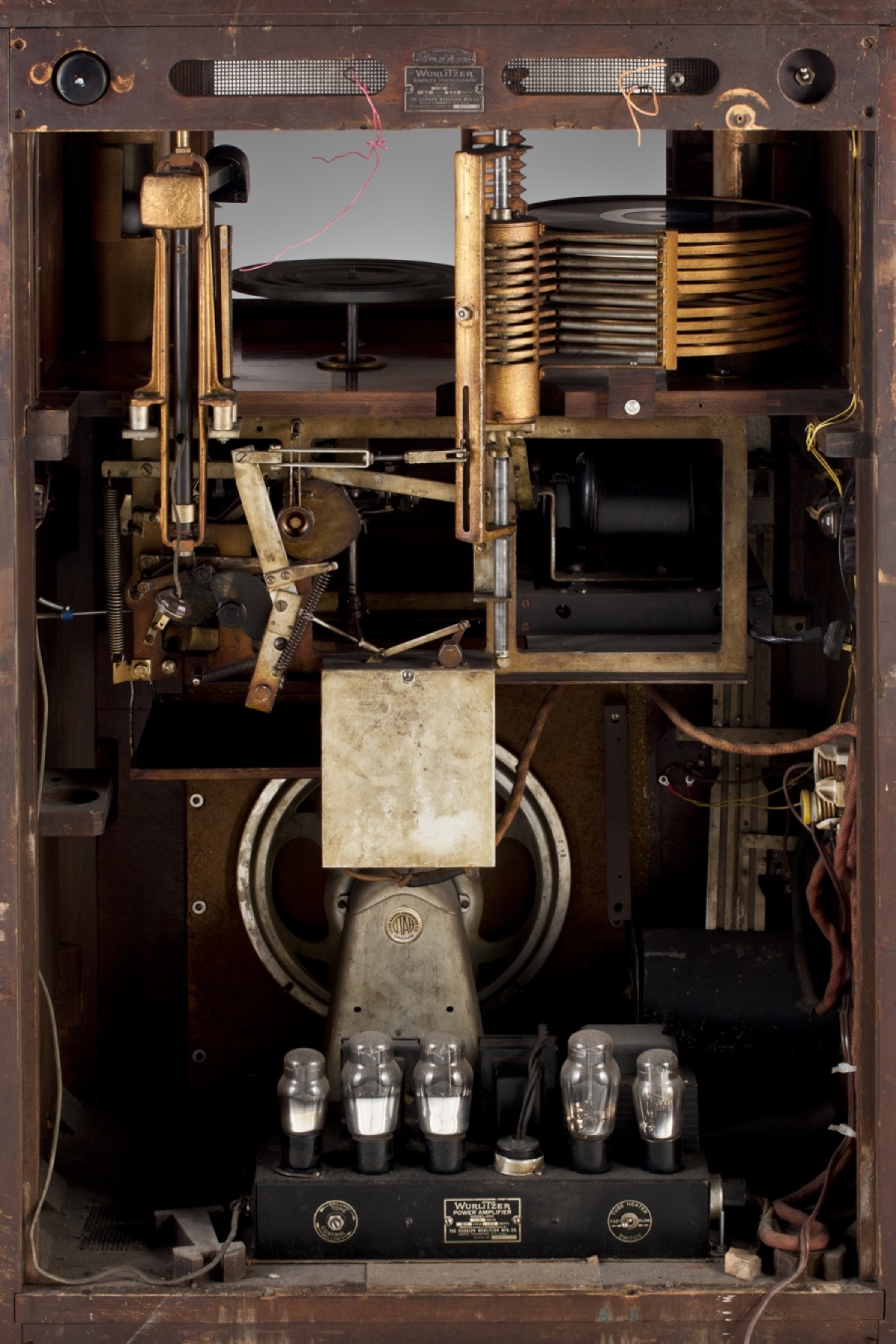

"1935 Wurlitzer P10 Open Rear" by Ken Brown, www.kenbrownart.com

Black Patti 8030

By Amanda Petrusich

Joe Bussard’s personal record collection consists of around 25,000 country, blues, Cajun, jazz, and gospel 78s, nearly all from the 1920s and ’30s, impeccably and mysteriously filed on floor-to-ceiling shelves in an order he knows but isn’t sharing. Bussard, one of the foremost living collectors of pre-war 78 rpm records, lives in a nondescript brick house in Frederick, Maryland, and while the ground floor was in a state of mild disarray on the afternoon I visited—two obese cats lounged amid piles and piles of stuff—the basement was an impeccably appointed oasis, an homage to recorded sound. Every wall was lined with memorabilia: record labels and sleeves, photographs, mementos, newspaper articles, advertisements, a signed letter from the astronaut John Glenn (“Dear Mr. Bussard, Thank you for your interest in and thoughtfulness in writing about the flight of the Friendship 7 spacecraft and for enclosing a token of appreciation”). The floor was carpeted, perhaps to preempt accidental record cracking, should a 78 ever slip from Bussard’s fingers. His record shelves were festooned with little cardboard warnings, typed in all caps on his Smith-Corona: please do not touch records. It never even occurred to me to try.

Watching Bussard listen to records is a spiritually rousing experience. He often appears incapable of physically restraining himself, as if the melody were a call to arms, an incitement it would be immoral if not impossible to ignore: he has to move. He sticks his tongue out, squeezes his eyes shut, and bounces in his seat, waving his arms around like a weather vane shaking in a windstorm, spinning one way, then another. At times it was as if he could not physically stand how beautiful music was. It set him on fire, animated every cell in his body. He only broke to check on me: Did I like it? He didn’t wait to find out.

“All that for a quarter!” he shouted.

“What a beautiful tone! Oh, my God!”

“It’s like they’re right there! You can hear everything!”

We went on like this for a while: Bussard scurrying over to his shelves, putting a record on the turntable, going nuts. He periodically held his hands up midsong, his palms out, like “Stop.”

“Listen to this,” he’d say. His voice was serious. “It’s taking everything.” Whenever I tried to scribble something in my notebook, he’d swat at my hand with a record sleeve, imploring me to pay better attention. To be held in rapture.

A couple hours passed in a haze of playback. Finally, Bussard erupted into his most famous junking story, a tale he clearly relished recounting, even now: the one about how he uncovered a stack of fifteen near-mint Black Patti 78s in a trailer park near Tazewell, Virginia, in the summer of 1966. This was what I’d come—what everyone comes—to hear.

After the record producer Mayo Williams left Paramount Records in 1927, he started a Chicago-based race imprint called Black Patti, named after the African-American soprano Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones, who’d earned the nickname because of her (supposed) similarity to the Italian opera singer Adelina Patti. The Black Patti label was festooned with a big, preening peacock, printed in muted gold ink on dark purple paper. (According to78 Quarterly, the late collector Jake Schneider once described it as “the world’s sexiest label.”) The Black Patti catalog—a total of fifty-five discs—included jazz songs, blues, religious sermons, spirituals, and hokey vaudeville-style skits; it was designed to compete with (and, they hoped, outsell) Paramount’s race series. The performances were recorded at several different studios, then pressed into shellac and shipped from the Gennett Records plant in Richmond, Indiana. Black Patti lasted about seven months. Not much is known about why the label collapsed, although it likely proved financially unsustainable for Williams and his two partners (Dr. Edward Jenner Barrett, the son-in-law of Paramount cofounder Fred Dennett, and Fred Gennett, a manager of Gennett Records), who unceremoniously shrugged off the whole enterprise in September of 1927. Rick Kennedy, the author ofJelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Studios and the Birth of Recorded Jazz, says it was Gennett who ultimately yanked the plug.

Now Black Pattis are wildly desired things, having been pressed in deliciously small quantities of one hundred or fewer each, and sold in just a handful of stores in Chicago and throughout the South. When I told the collector and producer Chris King that I’d spent a few weeks trying to track down sales or distribution records to no avail, he could barely suppress a guffaw: “They didn’t keep ledgers for this material,” he said. With a few exceptions, there are fewer than five extant copies of each Black Patti release, and some have never been found. In 2000, Pete Whelan, one of the earliest collectors of rare blues and jazz 78s, dedicated an entire issue of 78 Quarterly to the Black Patti: its cover features a dark, nearly indiscernible figure with gold eyes, emerging from the shadows and holding two Black Patti labels where her breasts would be. The tagline reads: “The most seductive feature ever!”

Although I’m not sure I find them quite so arousing, Black Pattis are certainly mysterious (that same issue of 78 Quarterly describes them as “historic, bizarre, and idealistic”). Most of the artists Williams recruited are now ciphers, with names like Steamboat Joe and his Laffen’ Clarinet or Tapp Ferman and His Banjo. A pipe organist named—confusingly—Ralph Waldo Emerson recorded five sides for Williams in 1927. Stylistically, the label was something of a mixed bag, but for collectors, its pull is unnerving.

In the summer of ’66, Bussard was on the road, running his usual Appalachian route in a Scout pickup. He thinks he must’ve had a buddy with him, but that bit of the legend is incidental, at least as far as Bussard is concerned. He got lost looking for a flea market. That sort of thing happened to him a lot. “So old dummy, old dumbass, I s’pose I made a right turn instead of a left turn,” he explained. There was a pause. “Best left turn I ever made.”

Bussard was getting into the story now, his blue eyes flashing like two synchronized traffic lights. “So I got down the road about a mile and thought, There’s no flea market down here. There’s an old man walking up the road, and so I ask him, and he says, ‘Yeah, it’s up there up the road.’ I said, ‘You goin’ up? Hop in!’ And I had a tape playing, some strange stuff. He says, ‘You getting that on the radio?’ I said, ‘No, it’s a tape.’ He said, ‘That figures,’ because, you know, he knew damn well there wasn’t anything on the radio any good. And we went up there and walked around and I didn’t find anything, of course. Then I told him what I was looking for.” Bussard was doing all the voices now: his, the old man’s. “He said, ‘I got a gang of them back at the house.’”

He drove the man the twenty-five miles or so to his house, a little shotgun shack behind a trailer park. “Sloppiest-looking place you’d ever seen—looked like a flood had hit it. And we went into this shack,” he continued, “and he goes down a hall, turns left, pulls a box out from under the bed.” Bussard felt that familiar churn of anticipation in his gut, but he knew deals like this could curdle quickly. The records might be garbage, or the man might decide at the last minute—when confronted with a stranger’s barely contained eagerness—that he didn’t want to sell after all.

“[The box] had so much dust on it—like snow, like a blizzard.” Bussard leaned in and mimed blowing the dust off the surface. His cheeks puffed up and deflated, like a cartoon’s. Bussard’s whole life would be changed—nearly defined—by the next five minutes, but he didn’t know that yet. “First record I hit was an Uncle Dave Macon. Average. Carter Family. Charlie Poole. And then the first Black Patti. I went down a little further. Three more! Phew! Finally I got to the bottom of the box, and there were fifteen of ’em. I said, ‘Where’d you get these records from?’ He said, ‘Oh, some guy gave them to my sister in 1927, we didn’t like ’em so we put ’em in the box under the bed.’ I said, ‘What do you want for them?’ and he said, ‘Ten dollars.’ And I said, ‘Ten dollars.’”

Bussard paid the man and booked it back to his truck. Almost immediately after he got back to Frederick, word got out about his find and offers started accumulating. First, Bussard said, was the collector Bernie Klatzko, who drove down from New York City and offered him $10,000 for Black Patti 8030, “Original Stack O’Lee Blues,” performed by Long Cleve Reed and Little Harvey Hull, the Down Home Boys. Although some Black Patti masters were also issued by other labels, like Champion or Gennett, and often with the performer using a different name, “Original Stack O’Lee Blues” was released by Black Patti exclusively, and in 1966, Bussard’s was the only known copy in the world. “So then after that happened, Don Kent called, he came down, offered me more. I had other offers. Went up to twenty thousand dollars, then twenty-five, then thirty, then thirty-five, then up to fifty thousand dollars.” Bussard darted over to the shelves. “Don’t look at where I keep it!” he said, pulling the record down and trotting back to his desk. He held it out to me in a way that suggested, “Take a nice long look, drink it in, but don’t you dare touch.” A mammoth grin spread across his face.

After Bussard felt I’d been sufficiently wowed by the sight of it, he pulled the 78 from its paper sleeve, laid it on his turntable, and wiped the surface with a record cleaning brush that resembled a blackboard eraser. Although Bussard repeatedly told me his was, in fact, still the only surviving copy of “Original Stack O’Lee Blues” on earth, Chris King would later whisper that he’d heard another had been uncovered and was in the possession of an unnamed collector in California.

All anyone knows about Black Patti 8030 is that this particular performance was recorded in a Chicago studio in May 1927. The song itself (also known as “Stagger Lee,” “Stagolee,” “Stack-A-Lee,” and other phonetically similar variants) is a tremendously popular, oft-adapted American murder ballad, first published in 1911—after the folklorist John Lomax acquired a partial transcription from a Texas woman, and the historian Howard Odum submitted it to the Journal of American Folklore—and first recorded in 1923 by Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians. It was likely written sometime in the very late nineteenth century. “Stack O’Lee” tells the story of the Christmas murder of a twenty-five-year-old levee hand named Billy Lyons, who was shot by a St. Louis pimp named Lee Shelton, who also went by the nickname “Stack” or “Stag.” According to Cecil Brown’s Stagolee Shot Billy, Lee was part of a gang of “exotic pimps” called the Macks who “presented themselves as objects to be observed.” They wore specially cut suits made from imported fabric—a nod to Parisian style—and wide-brimmed Stetson hats. The hat was important. As Brown wrote of it, “in that era it was a mark of highest status for blacks, coming to represent black St. Louis itself . . . To hurt a man symbolically, one could do no worse than cut his Stetson.” Brown also points out that Freud believed that at least in dreams, a hat was a symbol of “the genital organ, most frequently the male,” and that knocking someone’s hat off his head functioned as a kind of proxy castration.

That night, Shelton and Lyons were drinking in the Bill Curtis Saloon, a local bar and meetinghouse owned and operated by its namesake. It was also the default headquarters of the Four Hundred Club, a social and political organization composed of influential black men; Shelton was its captain. An 1896 story in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat described Curtis and his operation like this: “Though the Morgue and the City Hospital are regularly supplied with subjects from his headquarters, his popularity never declines, for it is generally conceded that he is acting as a public benefactor in allowing undesirable members of colored society to be dispatched in his place of business.”

Shelton and Lyons were seated at the bar, imbibing, exchanging thoughts. They were colleagues of sorts, if not necessarily pals. The conversation shifted, as it sometimes does, to a contentious topic—politics, maybe—and to augment or possibly accelerate the skirmish, Lyons decided to swipe Shelton’s prized Stetson from his head. Just reached up and swatted it off. It was a power move: childish but humiliating, nearly inconceivable in its hubris. Shelton demanded its return. There is no transcription of this exchange, but I imagine it was heavy. Lyons wouldn’t give it up. So Shelton whipped out his revolver, unloaded a few bullets into Lyons’s stomach, and—rather coolly, and with no outward indication of distress—reached down to collect and reposition his hat. Then he strolled out.

Lyons ultimately died from the wound, and Shelton was tried, convicted, and jailed in 1897. (Curiously, he was pardoned and released in 1909, but was reincarcerated just two years later for robbery and assault, and died in prison, reportedly of tuberculosis.) There is a Tarantino-esque brutality to the story, which has to do with pride, and vengefulness, and retribution, and all the accompanying lines in the sand, and if you were to maybe drink a whiskey and think about it for a bit, you know, what else was Shelton gonna do? Play keep-away with a petulant twenty-five-year-old? In his home bar, with his peers looking on? The narrative was swiftly adapted as a folk song and, as with almost any story, the details change depending on who’s telling it. Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and the Grateful Dead have all recorded notable takes; the Dead’s is set in 1940 and told from the point of view of Billy Lyons’s girl, Delia, who hunted down Stagger Lee on the night of Lyons’s murder and “shot him in the balls.” Beck’s 1996 single “Devil’s Haircut” was also an adapted version of the myth: “I had this idea to write a song based on the Stagger Lee myth. The chorus is like a blues lyric. You can imagine it being sung to a country-blues guitar riff,” he told Rolling Stone’s Mark Kemp in 1997.

There is nothing particularly interesting, from a contextual standpoint, about “Original Stack O’Lee Blues”—it’s just another take on a song everyone was already singing, performed by two people who don’t appear to have had much of a commercial career beyond it, although they did record a few other songs for Gennett, likely in the same session. Bussard’s interest in it was partially because of its scarcity, but had more (according to him, at least) to do with its aesthetic superiority. He thinks everything about it is perfect. Chris King doesn’t quite agree, although he acknowledges the enduring lure of a Black Patti. “I don’t think that the label’s cachet has diminished too much in the last twenty or thirty years,” he told me later. “Probably the only thing that has diminished are those collectors willing to shell out obscene money just for a rare-label disc that may or may not have much musical interest or power.”

Bussard spent a few minutes making sure he had the needle he wanted and then lowered it onto the record. His face went slack. He winced. His shoulders started scrunching up and down. It is, indeed, a lovely performance—particularly when Reed and Hull lean in to harmonize on the chorus, their voices entangled in just the right way. There is something sweet and melancholy in the guitar, a sense that violence is sometimes inevitable, that Billy Lyons and Lee Shelton were destined to destroy each other, like lovers or enemies, like we sometimes do. As soon as it was over, I thanked Bussard for playing it for me, and I meant it.

From Do Not Sell at Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records, by Amanda Petrusich, published by Scribner in July 2014.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.