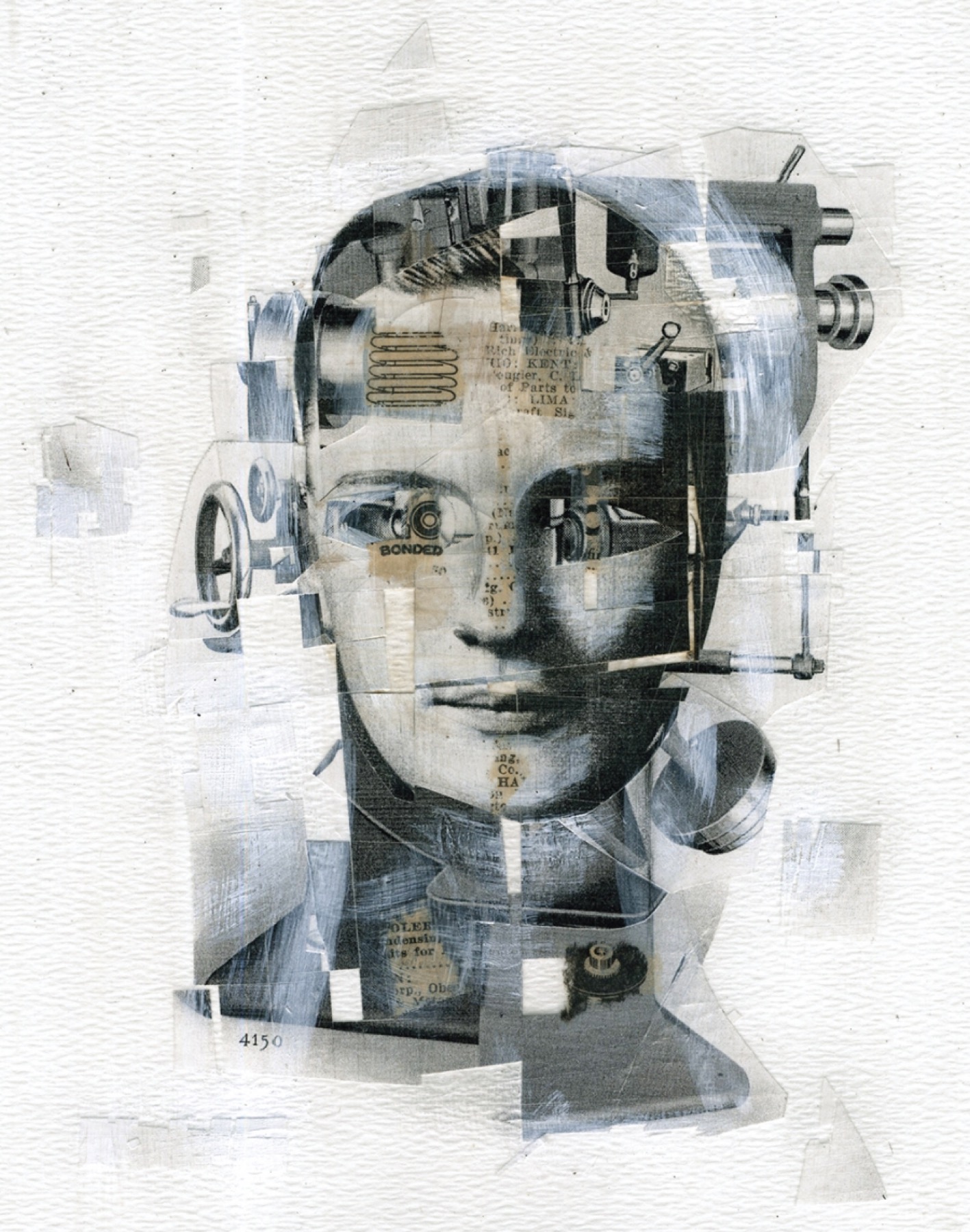

“M-4150,” by David Plunkert. Courtesy of the artist

An Unfinished State

By Wyatt Williams

There’s a story that Lance Ledbetter likes to tell about the history of barbecue in Atlanta. I’ve heard it several times. The short version is that Atlanta’s pitmasters never bothered with developing a local style because many travelers only wanted barbecue that reminded them of home.

In the long version, Ledbetter seems to imagine himself inside the details of the story. You might try that, too. Let’s say the year is 1923. The Atlanta Terminal Station is a massive Beaux Arts beauty flanked by a pair of gilded towers. As a train comes into the station, a horn blares and a cloud of white steam floats from the locomotive. Passengers disembark and stream into the lobby, their tickets punched from states all over, their hats cocked to shade off the sun.

The weather is nice and money is good because the country is between wars and not yet into the Depression. People are walking fast. They’re here on business with Sears-Roebuck, with General Motors, with Atlanta Life. Among the crowd, a man is yelling. He’s trying to get your attention. “Hey Carolina, we got your mustard sauce,” he’s saying. “Hey Carolina, we got your hot vinegar. Hey Kansas City, we’ve got those sweet ribs. Hey Texas, we got your brisket.” Ledbetter likes to tell that detail, his imitation of the barbecue barker.

Lance was born in 1976, four years after the Terminal Station was demolished to make room for a parking lot. He doesn’t really know what anyone hollered outside of barbecue joints a hundred years ago, though the story makes a lot of sense. Historically, Atlanta isn’t thought of as a place where things are from, aside from a bottle of Coke. It’s a train town, a crossroads, a place where people and goods and ideas and history pass through before finally arriving somewhere else. If you ask Lance to talk about Atlanta, to try to explain it, he’ll probably tell you that story about the barbecue. In his estimation, it explains just about everything.

We were eating barbecue, in fact, when Lance told me he’d given up on the Georgia project.

He and his wife, April, and I were having lunch at their house in the Ormewood Park neighborhood of Atlanta, where they live with their two long-haired cats, Louie and Maybelle, and where they run the Dust-to-Digital record company, a small label that specializes in the reissue of music old and obscure. It was summer and the mood was lazy and casual. While dishes of coleslaw, sliced peaches, white bread, and smoky pork were passed around the table, the conversation circled around, too. We gossiped about other record labels, talked about Korean food and where to get the best of it in Atlanta. Some of Bill Ferris’s field recordings played on the stereo. Eventually, I asked Lance if he was ever going to make another masterpiece.

Of course, I didn’t say it like that. The word makes people uncomfortable. But if you’ve made a masterpiece, people generally expect you to make another.

Twelve years ago, Dust-to-Digital released a six-disc compilation box set of spiritual recordings from the first half of the twentieth century called Goodbye, Babylon. The Ledbetters spent four and a half years working on the project and founded their record company for the purpose of releasing it. The set was quickly recognized as a classic. Sasha Frere-Jones described it as “incomparable,” “the ark of the covenant.” It was nominated for two Grammys. Bob Dylan gifted a copy to Neil Young, who called it “the original wealth of our recorded music.” I asked if they had any plans for something similar “in size and scope.”

“When I finished Goodbye, Babylon, I had a few projects on my desk,” Lance said, pausing for a bite of barbecue. “I wanted to make a CD of Christmas music. I wanted to do a sacred harp set. I wanted to recut Fred Ramsey’s Music of the South. And I wanted to do a box set of music from Georgia.” As Lance explained it, the Georgia project had been as ambitious as Goodbye, Babylon. The other projects were all finished now, but Lance said, “I think I’ve given up on Georgia.” April put down her fork and looked at him. She seemed surprised.

Lance and April have built their record company around a peculiar and bold musical vision. They mostly rerelease old, unfashionable music—the kind often known only to musicologists, university lecturers, and connoisseurs of the obscure—and repackage it in a way that is both easily accessible and artfully informed. Since Goodbye, Babylon, the company has focused mostly on other people’s projects: Art Rosenbaum’s field recordings, Jonathan Ward’s collection of early African recordings, David Murray’s Southeast Asian surveys, revisions of Alan Lomax projects, long-lost John Fahey tapes. These are not typical or chart-topping tunes, yet Lance and April have done the seemingly impossible, building the company into a solid business during what might be one of the worst decades for the record industry ever.

When Lance announced that he was giving up, I was intrigued and confused. How could his home state be more beguiling than, say, a compilation of 78-rpm recordings from rural Thailand? I asked Lance why he couldn’t see the Georgia project through. He said he’d take me down to the basement after lunch and show me what went wrong.

The Ledbetters moved into their house a couple years after releasing Goodbye, Babylon. Aside from a brief experiment with office space, they have run the record label from home ever since.

The house has recently been renovated and the rooms are airy, full of natural light, and clean. On the walls hang neatly framed artworks by Art Rosenbaum and photographs by George Mitchell, both iconic folklorists from Georgia and Dust-to-Digital collaborators. In the living room, new built-in shelves hold several hundred old records, some oversized art books, and a polished, gold-plated Gramophone trophy from 2008. Dust-to-Digital’s releases are routinely nominated for the “Best Historical Album” category at the Grammy Awards, as well as for lesser-known honors from organizations like the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, the Living Blues Awards, the Society for Ethnomusicology, and so on.

When I remarked to April that their shelves seemed tidy, she disagreed. “You can’t see what I see,” she said. “There’s no order over there, no organization. We’ll have to take care of that one day.”

If Lance is the visionary, the vigorously creative and abstract brain of Dust-to-Digital, April is the realist. They often work in the living room—sometimes with a third collaborator, a collector or a musicologist or an ambitious intern from Georgia Tech—listening to recordings, making notes, and talking through their projects. “Lance is constantly, totally in his head to a point that you have to snap him out of it sometimes,” she told me. “I tend to be more critical and say no to things and shut it down. I think he looks to me for that.”

Lance and April met while attending Georgia State University, where they both worked at the university’s art-house theatre, selling popcorn and movie tickets, loading the 35mm projector. One thing led to another. It was during that time that Lance started the research that would become Goodbye, Babylon. “When he first mentioned that he wanted to release gospel recordings, it was hard for me to understand,” April said. “I had grown up a Unitarian Universalist—we’re not known for our singing.” Despite that, April insisted that she could help with the project. They celebrated their ninth wedding anniversary this year.

Neither Lance nor April thinks of themselves as collectors. They often have occasion to work with serious collectors, people who have acquired enough recordings or objects or information that the physical mass of it fills their homes and metaphorically overflows their lives. The Ledbetters have seen enough to know that they do not want that for themselves, although that doesn’t mean they don’t constantly buy records or find things that they want to keep. Last year, they purchased the contents of a storage unit with more than twenty thousand records inside. They kept only a few and flipped the rest. By their measure, this kind of behavior means they are not collectors.

The basement, however, is a different story altogether. It’s roughly the same dimensions as the Ledbetters’ kitchen and living room, but the ceilings are low, there is only one window, and the dim space is cramped with boxes and files and ephemera and stacks of I’m not sure what—the unmitigated clutter of running a record label for the past decade. In the furthest, darkest corner is a pile of the well-intentioned, absurd things that most households accrue: tennis ball canisters, yard maintenance equipment, family heirlooms that have no function and yet cannot be thrown away. Lance waded into that area looking for the Georgia boxes.

I sat on a small chair near the window, close to a laundry basket filled with handpicked raw cotton, while he brought out the archives one by one. There were two large cardboard boxes, a lidded white box shaped for holding standard envelopes, and a couple of airtight plastic containers that someone else might use for the transportation of a large casserole. Lance was about to open one of the plastic containers when he changed his mind, leaned over to a desktop computer, and summoned up an old correspondence.

The email, dated April 2004, is addressed to the music historian Tony Russell. Lance read it aloud.

Hey Tony,

How are things? I saw where your discography has been pushed back to summer. As I’m sure many people feel, I can’t wait for its release.

The reason I’m writing is because there has been a bit of a change of plans for the next big release on Dust-to-Digital. . . .

So what’s the project? It’s a box set of artists from Georgia. The blueprint right now is to approach the material by artists’ county origin, but as you know things are always subject to change. The good news is that my preliminary research shows that this could be quite possible.

Anyway, I have assembled a list of Georgia artists and attached it to this message. If you do not mind, I would very much appreciate if you could take a look at it and offer any suggestions/corrections. You’re also invited to assist as much as you want in the annotation phase. I know you’re busy, but I just wanted you to know the invitation is there. . . .

I hope you are still enjoying your copy of Goodbye, Babylon.

Kind regards,

Lance

Russell is one of the world’s foremost experts on old-time music, the big tent of Appalachian folk musics that predate what we call country music today. He founded the now-defunct magazine Old Time Music in 1971. The discography that Lance casually mentions at the beginning of the email is Country Music Records, a 1,200-page book that documents “every commercial country music recording, including unreleased sides, and indicates, as completely as possible, the musicians playing at every session, as well as instrumentation” between the years 1921 and 1942. At the time Lance emailed him, Russell had been working on the discography for twenty years. Oxford University Press published it in September of 2004.

Russell was happy to oblige Lance’s request. “Goodbye, Babylon signaled that there was an enterprising and fresh-thinking new player in the historical-reissue arena,” he recently told me. “I immediately realized that Lance was someone with what seemed to me to be the right attitude to the subject: fascinated, questioning, open-minded, dedicated. We became friends immediately.”

Russell lives in London, but he and Lance quickly started collaborating on the Georgia set by email. Their correspondence is enthusiastic and obscure, full of excitement and praise for this string band and that fiddle player, brimming with long lists of names like Doctor Clayton, South Georgia Highballers, Sloppy Henry, Seven Foot Dilly, and on and on.

Lance also wrote to Joe Bussard, perhaps the best-known 78-rpm record collector in the world, and asked for him to make a copy of every single recording from Georgia in his collection. Like Russell, Bussard obliged. When the package finally arrived, there were forty hours of music inside and it reeked so heavily of cigar smoke, Bussard’s preferred vice, that Lance had to leave it outside to air out before he could listen to the tapes.

The project was starting to loom large. “It was Lance’s idea, with which I agreed,” Russell told me, “that the Georgia set—envisaged at that time as maybe ten CDs—should include all the music made in Georgia in the period under review: old-time, blues, jazz, pop, gospel and sacred music, and so forth.” Even for something so ambitiously all-inclusive, there was the matter of where to draw the borders. “We debated whether we should include only commercial recordings or also embrace field recordings made by folklorists,” Russell said. “We also debated at what point we should cut off. If we confined ourselves to commercial recordings, would we stop with the death of the 78 or carry on through the 45 era?”

Deciding when to chronologically begin a project about the history of recorded music in Georgia is actually quite simple. On Thursday, June 14, 1923, an Okeh Records engineer named Ralph Peer made the first recordings in Atlanta. One of the songs he cut, “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” by Fiddlin’ John Carson, went on to sell nearly a hundred thousand copies, convincing several New York record companies of the financial viability of traveling to Atlanta and other cities to record Southern musicians. As sometimes happens with moments in music history, almost every other detail about that day in 1923 is a matter of debate.

The most-repeated version of the story begins with Polk Brockman, an ambitious, young Atlantan who ran the phonograph section of his grandfather’s furniture store:

Brockman makes a name for himself with Okeh Records by selling more units than any other regional retailer, so the company invites him up to New York for a meeting. On his way to the office, Brockman ducks into a movie theater in Times Square to watch the newsreels and sees a clip of a fiddle competition in Virginia. The light bulb goes on above his head—he decides to convince the record company to come down to Atlanta to record a fiddle player he knows. At the time, record companies were shipping artists up north to record, but none of them had thought to send a record producer down to the South. Brockman’s gambit works. Okeh sends Ralph Peer, who records Fiddlin’ John Carson in a vacant loft on Nassau Street that Brockman rented out for the occasion. Even though Peer thinks Carson is “pluperfect awful,” Okeh presses five hundred copies of the record in time for a fiddle competition at the Atlanta Municipal Auditorium in July. The record sells out in a single day. History is made, the first Southern music recorded in the South. You might could call it the birth of country music records.That’s essentially the story that Archie Green dug up for “Hillbilly Music,” a 1965 article for the Journal of American Folklore. It is a stunning and impressive bit of research, aside from the fact that about half of those details are probably wrong. According to Barry Mazor, whose biography of Ralph Peer was published in 2014, Okeh’s recording session in Atlanta was meant to focus on Warner’s Seven Aces, a society band that played the light dance pop of the time, and it had been planned weeks before the day when Brockman could’ve seen that fiddle player on the newsreel. Carson, Mazor claims, had been an afterthought, and the recording took place on June 19 in a warehouse on Nassau Street, not a vacant loft. As for the “pluperfect awful” quote, the most famous detail of Green’s story, Mazor attributes that to something Brockman said in an interview decades later in reference to Peer’s opinion of the recording equipment. Peer probably never said it.

Green’s research concerned the origins of recorded country music, but what he actually described is quite larger. The same recording session in 1923 that produced Fiddlin’ John Carson’s first record also recorded blues singers Lucille Bogan and Fannie Mae Goosby and the Morehouse College Quartet singing gospel tunes. So what we’re talking about isn’t just the first country music recording session in the South, but the first blues record made in the South and the first gospel record made in the South, too.

When I called Mazor about this, he said, “When people write about the history of country music they leave out the blues and the other way around. They keep it separate even though it wasn’t. People create these imaginary separated worlds, like these musicians were on different planets, when in fact they were standing in the same room, waiting to record their records one after another.”

Histories tend to get shaped more like Green’s version: the easy epiphany, the quotable punch line, any tricky context sifted out. The most durable stories tend to be the least complicated versions. If you ask about the birth of country music records, you’re much more likely to hear about a session in Tennessee in 1927, when the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers first recorded. And if you’re looking for the early days of blues, people tend to point toward more mythical settings: foggy crossroads, disappearing travelers. Mississippi’s crossroads and Nashville’s star-making machine turned out to be durable stories. The birth of Southern music in Atlanta doesn’t get talked about the same way. Nobody has ever even figured out which building on Nassau it happened in. Today, the place is probably a parking lot.

Musicians in Atlanta, ca. 1915. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Dust-to-Digital and Todd Gladson

Musicians in Atlanta, ca. 1915. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Dust-to-Digital and Todd Gladson

While explaining all of this in his basement, Lance had started to unpack boxes. The speakers were tuned to songs from the years following that first recording on Nassau Street. Sloppy Henry’s “Canned Heat Blues” floated around the room, moaning complaints of unforgiving whiskey and alleyways. Lance was trying to explain the chronology of his work on the Georgia set, but the contents of the boxes kept surprising him. He’d be talking about a trip to Oregon that he and April took to visit the researcher Norm Cohen, and then a telegram from Ralph Peer would emerge from one of the boxes, instructing some guy in 1928 to cheat Victor Records out of a contract with a sacred quartet by using fake names.

“Look at this!” he’d say spontaneously. “This is Clayton McMichen talking—this is an interview that somebody did when he moved to Kentucky. He’s one of the great Georgia artists. Oh, and look at this, this is an oral history somebody did with Riley Puckett. Look at all that. Where he was born, where he died, all his children.”

He pulled out a stack of Columbia advertisements and Okeh catalogs and it seemed like every other artist was from Georgia and recorded in Atlanta. “At one point in time, we were the representation of traditional music in the South,” Lance said. “If you bought a country record in 1927, it was probably a Skillet Lickers or Fiddlin’ John Carson record. If you bought a gospel record, it’s probably going to be a J. M. Gates. Those were the ones selling.”

There were old photographs of young men and women posing with their instruments, proud and preening. There were stacks of typewritten interviews, death certificates, radio programming sheets. What Lance had been compiling was not just a collection of songs, but a portrait of a time in which Atlanta had been the thriving center of recorded Southern music.

“For people who overlook or don’t understand what Georgia music sounds like,” he said, “I wanted to put it all together, so that you could understand it. The originators of country and twelve-string blues and gospel preaching on record, they were all in these rooms at the same time in Atlanta waiting to play one after another after another after another. They were at house parties on Hemphill. They were at the barbecue restaurant on Ponce. They were at the furniture store on Nassau.”

But the Atlanta recordings weren’t enough. As Lance had said in his email to Tony Russell, he wanted to create a collection that would contain the whole geography of the state, county by county if possible. Musicians were traveling into Atlanta to record in the twenties, but they were largely from the northern half of the state. There had been one recording session in Savannah from around that time, but that was it.

To cover all of Georgia, he kept extending the years of focus, expanding the styles of recording. He gathered field recordings and 45s of jazz, quartet gospel, field work songs, the Sea Island singers. Still, there wasn’t enough to cover every county. Georgia has 159 of them (only Texas has more), and many are tiny, obscure, barely populated locales. Lance hadn’t anticipated that.

The boxes had been carefully arranged, but Lance couldn’t always remember what the arrangement was. The files were meticulous. Just looking at the neat stacks, the careful preservation, you could see the efforts of a hand trying to keep something very big under control. As we unpacked box after box, file after file, I could see how things had gotten out of hand. There was too much. Even with the necessary knowledge required to make connections that hardly anyone else would notice, connections that would bring these documents to life, the information, the history before us, all under the loose umbrella of state lines—

Don’t your room seem lonesome when your gal pack up and leave?

Don’t your room seem lonesome when your gal pack up and leave?

You may drink your moonshine, but your heart ain’t never pleased.

That was Barbecue Bob interrupting us, reminding us to listen to the music, the tunes coming out of the basement speakers—wasn’t that really the point?

We listened to a commercial jingle, “I Got Your Ice Cold NuGrape,” that somehow possesses the warm depth of a gospel number. Then we listened to a sermon by J. M. Gates admonishing his parishioners, telling them to pay their furniture bills. Then we heard Bobby Grant’s “Lonesome Atlanta Blues,” a tune as lonesome as it was eighty years ago. Gid Tanner and Riley Puckett played “Tanner’s Boarding House,” a dancing song with an off-kilter rhythm that makes your head light like a shot of moonshine would. Music, no matter how old, is always in the present tense. It has the funny effect of taking you into a fully different moment for three minutes at a time.

Lance calls his creative process “focused listening.” It isn’t anything like what we were doing, hanging out, listening to songs and talking. He sits with his eyes closed, computer screen off, headphones on, and listens this way for as long as he can, sometimes hours, making notes on paper, forming connections, looking for the ways that music can explain itself. He worked this way on the Georgia set for some years, until he didn’t anymore.

The short version of Lance and April Ledbetter’s story is that they run a record company. This is true. They spend lots of time acquiring legal rights, designing or approving packaging, scheduling release dates, fulfilling orders, coordinating with distributors, and all of the other logistical tasks that tend to occupy any other record label. Only, the things that make Goodbye, Babylon great have little to do with any of that.

It is a compilation of 135 songs and 25 sermons recorded between the years 1902 and 1960. Rather than organizing songs by genre or chronology or geography or any other familiar rubric of commercial music, the set is arranged by spirit and mood, around concepts of “Judgment” or “Deliverance” or “Salvation.” The line that tends to separate gospel and blues—that is to say, the line between the sacred and profane—is obliterated here, as is the line between pretty much any other form of American vernacular music. To listen to all seven hours of it in one sitting is to experience a new story of American music told through the contours, the ecstatic highs and sorrowful lows, of sermon. The compilation is housed inside a cedar box packed with balls of raw cotton, a design that says, “This is important.”

The Ledbetters’ style belongs to an artistic tradition that began with Harry Smith’s 1952 release Anthology of American Folk Music. The music, recorded between 1926 and 1934, is subtly organized by the classical elements of water, fire, and air. Smith subscribed to some idea of alchemy, the fundamental concept being that certain materials could be combined to create a sum greater than the parts. Base metals into gold. Plain liquids into the elixir of life. Old forgotten songs into a novel vision of American music. The Anthology is, in a way, a template of that idea.

These creations are imaginary experiences, shaped as much by the original recordings as they are by the connections and idiosyncratic knowledge of the curator. Essentially, that’s the method of collage, the dominant art form of the twentieth century. The trouble is that music history tends to prefer oversimplified stories, rubrics like genre or dates or race.

The Georgia set could have been the Ledbetters’ follow-up to Goodbye, Babylon, but, of course, the Georgia set was never finished. Lance and Tony Russell ended up collaborating on other projects, smaller things that have since been completed. The label has released other sets arguably as good—their collection of Art Rosenbaum’s field recordings received a Grammy—but they are other people’s projects, other people’s life works, not Lance and April’s. Neither of them could say exactly why they couldn’t finish the Georgia project. They tried to explain that there were too many counties or that the concept got too big or that it went on for too long and finally lost momentum. Songs that had been obscure or almost impossible to find started appearing on YouTube, on Spotify, places that hadn’t even existed when they started. Lance stopped seeing it as a financially viable release. That’s when it went into the boxes in the back of the basement.

Lance said that admitting he was finally giving up was a way of unburdening himself from the whole thing. So many people had offered to help, to give their own research that they wanted someone else to use, their own collections that they wanted someone else to hear. “There’s a lot of people who have done incredible research over the years that just don’t know what to do with it,” Lance said. “People are burdened by that, by having information but not having an outlet to share it.”

Of course, it is entirely possible that the Georgia set wouldn’t do much to shift the historical record. No matter how well a story is told, there’s no guarantee that people will listen to it. No matter the power and clarity of the music and history that Lance had been able to compile, there’s no guarantee that it would’ve been anything but another box full of CDs in the Dust-to-Digital basement, waiting to be packed away for the slow trickle of mail order.

That isn’t a very optimistic version of the story. Russell told me that he still hoped they could finish it one day. “Between 1923 and 1932, a greater number of first-rate blues, gospel, and old-time music recordings was made in Atlanta than anywhere else,” he said. “This could be a set that blazoned to the world Georgia’s vast contribution to American vernacular music. In my view, the door should be kept open for such a possibility.” Perhaps the Georgia set could have been a revision to the slights of history, a new genesis story for the whole Southern music universe.

It was getting late in the basement. Lance and I had been talking for hours and the conversation had finally gone quiet. We were looking at a photograph of a couple dozen men holding fiddles and banjos, maybe standing outside the Atlanta Municipal Auditorium, maybe somewhere else. The picture must have been taken sometime in the twenties, or earlier. The men wear suits and ties, their hats cocked coolly to the side. They have thousand-mile stares. Maybe they had train tickets in their pockets, maybe they had arrived that day. Lance pointed to Fiddlin’ John Carson. It wasn’t hard to pick out the guy they called Seven Foot Dilly. The other men had names, of course, but they might be lost to history by now. Lance said the picture had never been published anywhere, probably hadn’t been seen by much of anyone since it was taken. He was looking at it intently. He seemed to be able to see it more clearly than I could. Maybe he could imagine himself inside the scene. We were still listening to that old Atlanta music. The past seemed awfully present.

That’s when Lance looked at me and said, “I don’t want to say it will never happen.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.