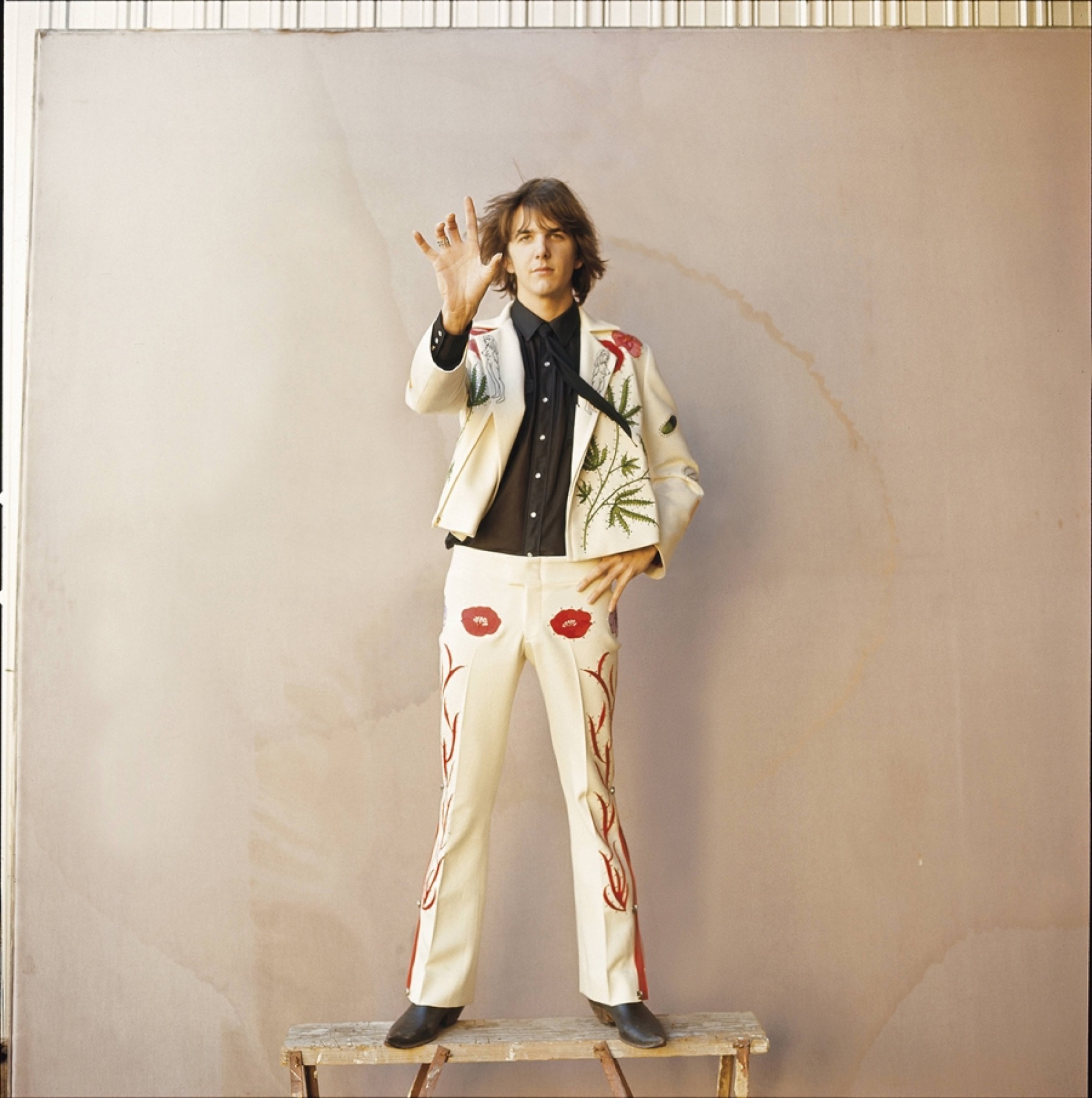

Gram Parsons. © Jim McCrary/Getty Images

Nudie and the Cosmic American

By Elyssa East

The 1960s were coming to a close when rising country rock musician Gram Parsons posed next to Nudie Cohn, the celebrated Western-wear designer more than three times his senior. Raeanne Rubenstein shot their portrait for Show: The Magazine of the Arts at Nudie’s Los Angeles workshop. Over a smooth bare chest and midriff, the twenty-something Parsons wore the suit Nudie designed for him for the cover of the Flying Burrito Brothers’ debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin. Made of white cavalry twill, it was embroidered with crudely rendered naked ladies, rhinestone-studded marijuana leaves, and sequin-dotted poppies. Tuinal and Seconal capsules and sugar cubes laced with LSD decorated the sleeves. On the back shined a giant, gleaming cross. Flames licked the sides of both bell-bottom legs. Rubenstein’s shutter clicked, capturing the near-familial warmth and affection between the two men, neither of whom would have predicted that the suit, which went on to help make Parsons a legend, also foretold of his death.

Nudie, who came to Hollywood in the 1940s and hung his hat as the “Rodeo Tailor,” was legendary for creating what we think of today as an iconic American look: flashy Western high style. Born Nuta Kotlyarenko to a Jewish family in Kiev, then part of the Russian Empire, he immigrated to America in 1913, when he was eleven, and a customs agent on Ellis Island renamed him “Nudie Cohn.” He went on to dress the preponderance of Hollywood’s cowboys—Roy Rogers, Dale Evans, John Wayne—as well as country music’s biggest stars, from Hank Williams to Johnny Cash. Nudie’s first designs depicted classical Western motifs in rhinestones: cactuses, covered wagons, hearts, and roses. In 1957, he designed Elvis’s most famous outfit: the gold lamé suit the King wore on the cover of 50,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong. (The suit cost Elvis $10,000, equivalent to $85,000 today.)

Many consider Parsons’s “Nudie suit” to be the designer’s masterpiece. Nicknamed “Sin City,” after a song on the Burritos’ album, the suit has been called “the Sistine Chapel ceiling of cowboy attire” by Guardian critic John Robinson. It is a study in dualities: vice and sanctity, irony and earnestness, and country music style and rock & roll sensibility. Aesthetically, it is the perfect visual expression of Parsons’s music, which melded country to rock and gave rise to an entirely new sound. Bands such as the Eagles, the Doobie Brothers, and later-generation artists Uncle Tupelo, Whiskeytown, Old 97’s, and Steve Earle—and the entire Americana and alt-country movements—would be inconceivable without the example Parsons set. Contemporary musicians such as Jack White and Jeff Tweedy continue to wear Nudie- and Parsons-inspired looks to this day.

Ingram “Gram” Cecil Connor was born into a family of wealth, thanks to his grandfather’s citrus empire. In his native Waycross, Georgia, he often traveled in chauffeured Cadillacs and journeyed to Florida in plush, private train cars. At age nine, Gram saw Elvis Presley open for Little Jimmy Dickens at the Waycross City Auditorium, an experience that changed the budding musician’s life. In Twenty Thousand Roads, a biography of Parsons, David N. Meyer quotes Gram’s nanny, Louise Cone: “Gram was a sweet child as long as you let him be Elvis Presley.”

Parsons also knew suffering. Two days before Christmas of 1958, when Gram was twelve, his alcoholic father, Ingram Cecil “Coon Dog” Connor, committed suicide with a bullet to his head. Gram moved to his grandparents’ family compound in Winter Haven, Florida, with his mother, Avis, and little sister. A few months later, Avis married a smooth-talking, slickly dressed man named Robert Parsons, and Gram Connor officially became Gram Parsons.

When he was fifteen, Parsons performed in a band called the Legends—they wore matching red blazers and traveled to gigs in a customized VW bus detailed with the band’s name. Parsons, whose family had hired a manager for him, traveled to Greenville, South Carolina, to a solo gig on the Coca-Cola Hi-Fi Club Hootenanny, where he met and joined the Carolina-based, Journeymen-inspired Shilos. The band spent the summer after Parsons’s junior year in New York City playing the legendary folk clubs Café Wha?, Café Rafio, and the Bitter End. Back in Florida, on the day of Parsons’s high school graduation in 1965, his hard-drinking mother died from cirrhosis of the liver.

It was a pivotal year for Parsons, who headed to Harvard, and for American music. That summer, Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival, a move that kicked folk back to the dustbin. Country was readily accessible across the U.S., but as Parsons’s eventual bandmate, guitarist John Nuese, told biographer Meyer, “Nobody was listening to what they’d call redneck country-western shit.”

Parsons dropped out of Harvard after one semester, moved to New York City with his musician friends, and formed the International Submarine Band. While he’d had a strong formative exposure to country in Georgia and Florida, it was Nuese who introduced the band to contemporary twang, including the genre’s older, more obscure ballads and songs. “We were discovering the depths of how impassioned that music is,” said ISB bassist Ian Dunlop. “It’s magnetic and terrifically poetic. It’s the human condition exposed.”

The band spun and studied modern albums by Bakersfield musicians Merle Haggard and Buck Owens, as well as George Jones. Though Parsons didn’t know him yet, Nudie had already dressed all three of these men; as his designs matured, he made special stage suits for artists in celebration of their greatest hits. He embellished a black suit with moonshine bottles and lightning bolts for Jones’s first No. 1 country single, “White Lightning.” For Webb Pierce’s hit version of Jimmie Rodgers’s “In the Jailhouse Now,” Nudie covered the front of a suit with jailhouses and on the back embroidered a picture of Pierce strumming a guitar behind bars.

By the spring of 1967, the ISB moved to Los Angeles, where things finally began to come together musically for Parsons. In 1968, the ISB cut an album, Safe at Home, that had a unique, countrified rock sound informed by the band’s deep study of Americana. But before the album was released, Gram left the group to join the most popular band in the country: the Byrds. He lasted only six months. Still, it was long enough for him to lead them to completely change their sound for Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which Country Music Hall of Fame writer Peter Cooper described as “the gateway drug to country.” Cooper also stated, “Gram turned the Byrds from America’s most popular rock band to one of America’s least popular country bands.” Audiences didn’t yet know what to make of the marriage of the two genres. Parsons called it “Cosmic American Music.”

The divide between rock and country held true in fashion, as well. Pianist David Barry, who was active in the L.A. music scene, said, “People like me wore jeans and boots, which is exactly what real country stars didn’t want to wear because it suggested they came from country’s poor white roots.” The “real” country stars “looked like a Las Vegas joke.”

In the late 1960s, Nudie’s son-in-law and head tailor Manuel Cuevas met Parsons and enticed him into Nudie’s shop. In addition to working for Nudie, Manuel, who goes by his first name professionally, was working on crafting the Grateful Dead’s skeleton-and-roses insignia and designing the suits for the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album. Soon after, Parsons began sporting Nudie’s outlandish creations as the visual corollary to his unique sound. Nudie would hop in his custom Western-themed Cadillac convertible, with pistols for door handles, a hand-tooled leather dashboard covered in silver dollars, horseshoe hood ornaments, and steer horns jutting forth from the front grill, and drive to the clubs to hear the band play. Parsons had started a new band called the Flying Burrito Brothers with Chris Hillman, another ex-Byrd. “Nudie loved seeing Gram up on the stage, sparkling and looking so beautiful in his designs,” said photographer Raeanne Rubenstein. When it came time for the Burritos to record their debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, Nudie was the obvious choice to help put together their look.

Nudie and his staff made outfits for all four of the Burritos, each to their own tastes and whims. Hillman, who played guitar and shared vocals and songwriting credits with Parsons, opted for a lush cobalt blue suit with peacocks on the front and a giant sun on the back. Peter “Sneaky Pete” Kleinow, the band’s pedal steel player, requested a suit embroidered with a pterodactyl and a tyrannosaurus rex. Bassist Chris Ethridge asked that his Edwardian frock coat and pants be covered in a classic motif of red and yellow roses. “We talked for months and months before we put it together,” Manuel told me. He stitched the embroidery on Parsons’s suit himself because Rose Clements, Nudie’s chief embroiderer, refused to sew the pictures of drugs and naked women.

Parsons may have been going for an authentic country look, but his suit was equally tongue-in-cheek, like some of his songs. The rhinestones and cross are in homage to classic country culture, while the marijuana gave a blatant middle finger to that world. The suit cut the other way, too, celebrating hippie drugs in high redneck style. Nudie’s designs conveyed a subtler narrative—that of the Southern innocent forever corrupted by urban life. In country music, the narrator often ends up calling the past his home, but Parsons’s past offered no solace.

Though now considered a classic, The Gilded Palace of Sin sold dismally. Rolling Stone critic and fellow Waycross native Stanley Booth gave it a rave review and Dylan said the album “instantly knocked me out,” but the Burritos’ music was still too rock for country audiences and too country for the rock set.

At the time, the album’s greatest success belonged to Nudie—four months after Gilded’s release, he was featured on the cover of Rolling Stone. Before long, John Lennon, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, Sly Stone, and Bootsy Collins, among others, would all wear his styles, inspiring Western wear’s popularity in the 1970s. But in early 1968, the Burritos caught flack for their bedazzled attire. “Just because we wear sequined suits doesn’t mean we think we’re great,” Parsons said. “It means we think sequins are great.”

The drugs that decorated “Sin City” eventually began to catch up to Parsons; he had started using barbiturates and heroin. In April of 1970 he released a middling second album with the Burritos, Burrito Deluxe. Two months later, Hillman, who was growing tired of Parsons’s “rock-star games,” fired him on the spot when he showed up late and high to a gig. Afterward, Parsons went to hang out with Keith Richards, with whom he’d developed a friendship solidified by drugs and music, at Nellcote, the French villa where the Stones were recording Exile on Main Street. Today, many attribute the band’s new direction on that album to Parsons’s influence, particularly its twangier numbers, even if the Stones did boot him from their idyll.

Eventually, Parsons got clean enough to cut a solo album, GP, featuring the harmonies of Emmylou Harris, then an unknown. Rolling Stone reviewer Bud Scoppa saw Parsons and Harris perform during their tour, and wrote: “That night—for me, at least—Gram Parsons was transformed into a latter-day Hank Williams: an innovator still revering the past and proud to be bound to it, an anguished genius daring to use his pain as the foundation of his art, no matter what the consequences. He was beautiful, but there was danger in the beauty.”

Hank Williams had been a client of Nudie’s, and the two had grown close before Williams’s tragic death at twenty-nine. Likewise, Parsons and Nudie developed a strong bond. “Nudie took him under his wing like he would a son,” according to the designer’s granddaughter Jamie Lee Nudie. But, she remembers, Nudie’s wife, Bobbie, often said that there was simply something deeply sad about Parsons.

After the tour for GP, Parsons was arrested for getting into a drunken, drug-inspired bar fight, and Nudie bailed him out—but no one, not even Parsons’s closest friends, could save him from himself. “Nudie saw what was happening, and it devastated him,” said Jamie Lee.

In 1973, at twenty-six, Parsons died of an overdose in Joshua Tree, California, right before the release of his follow-up solo effort, Grievous Angel. Gram had traveled far in his short life, but ultimately could not escape the illness that also claimed his parents’ lives: addiction.

Though Parsons is not a Country Music Hall of Fame inductee, his Nudie suit is on display at the museum, where it celebrates Parsons’s and Nudie’s respective revolutionary approaches of conjoining two otherwise opposing aesthetics: country and rock. Filling a glass case between two guitars, the suit also stands as a compelling sartorial portrait of Parsons the man and musician, the sinner and seeker. Like much of his Cosmic American Music, it is made all the more haunting for its irony and beauty, and the story of its grievous angel whose life was shot through with loss.

“Brass Buttons” by Gram Parsons appears on the Georgia Music issue CD

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.