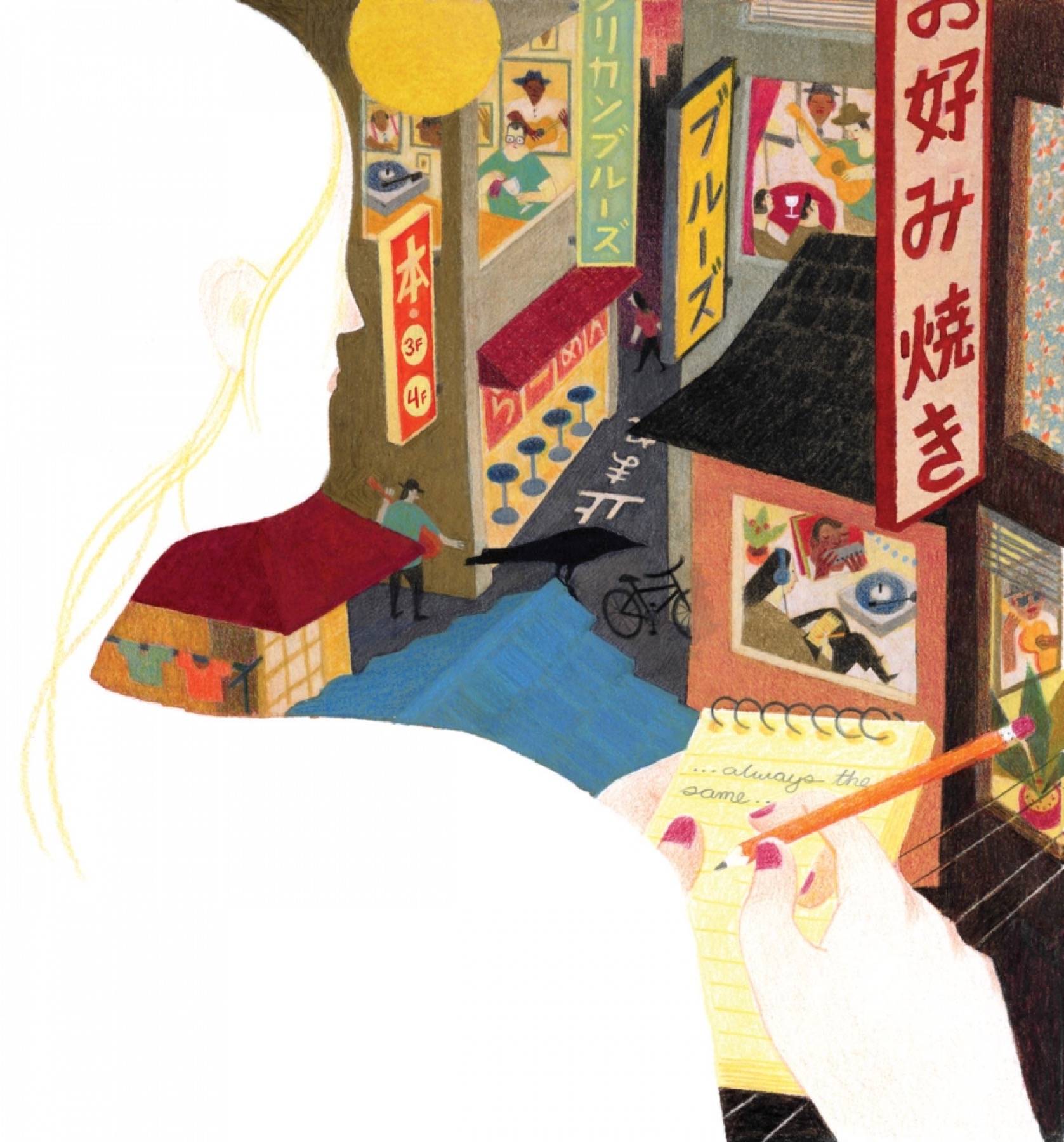

Illustration by Eleanor Davis

Sweet Bitter Blues

By Amanda Petrusich

Encounters in Tokyo

The curling streets and alleyways of Shimokitazawa, a scrappy neighborhood on the western edge of Tokyo, are too narrow to comfortably accommodate an actual automobile. But on foot, a person can easily lose an afternoon wandering its attenuated paths, browsing racks of crinkled vintage t-shirts and shelves of enamel cookware, supping complicated, multi-ingredient cocktails. Tourist guides describe the area as “endearingly haphazard” and “meticulously inelegant.” It is, perhaps, a Japanese approximation of Brooklyn’s approximation of some bohemian European enclave. Young people congregate in its bars and cafés, fiddling with devices, smoking, looking stylishly aggrieved.

I was in Shimokitazawa to see Steve Gardner, a singer and blues guitarist from Pocahontas, Mississippi, play a tiny club called Lown. American blues performers—purveyors of “black music,” as it is known colloquially here—can find good work in Tokyo and its immediate environs. I’d first gleaned something about the Japanese appreciation for specific tributaries of American vernacular music several years ago, when I was reporting a book about collectors of exceptionally rare 78 rpm records. Artifacts of a certain era tended to drift peaceably but steadily across the Pacific—coaxed east, I was told, by affluent and eager bidders.

I couldn’t quite figure out why Japanese listeners had come to appreciate and savor the blues in the way that they seemed to—lavishly, devotedly. Blues is still an outlier genre in Japan, but it’s revered, topical, present. I’d spent my first couple of days in Tokyo hungrily trawling the city’s many excellent record stores, marveling at the stock. I had shuffled into the nine-story Tower Records in Shibuya (NO MUSIC NO LIFE, a giant sign on its exterior read), past a K-pop band called CLC, an abbreviation for Crystal Clear—seven very-young-looking women in matching outfits, limply performing a synchronized dance, waving their slender arms back and forth before a hypnotized crowd—and ridden an elevator to a floor housing more shrink-wrapped blues CDs than I have ever seen gathered in a single place of retail. I had been to a tiny, quiet bar—JBS, or Jazz, Blues, and Soul—with floor-to-ceiling shelves housing owner Kobayashi Kazuhiro’s eleven thousand LPs, from which he studiously selected each evening’s soundtrack. I had seen more than one person wearing a Sonny Boy Williamson t-shirt. I had heard about audiophiles installing their own utility poles to get “more electricity” straight from the grid to power elaborate sound systems. What I didn’t know was what about this music made sense in Japan—how and why it had come to occupy the collective imagination, what it could offer.

A few hours before Gardner’s set, I ducked into a subterranean restaurant called the Village Vanguard (its name was presumably an homage to the famed New York City jazz club, though I could not discern any literal or even spiritual link between the two establishments). A sign on the door identified it as an “almost hamburger shop.” I ordered the hamburger. Norman Rockwell prints were nailed to the walls, alongside framed pages from Life magazine. “Paradise City” bleated from overhead speakers. The décor evoked the interior of the roadhouse from Thelma and Louise, except the bar itself was tiki-themed, bedecked with lights and plastic tropical flowers. I was trying to develop some richer understanding of how the Japanese metabolize and reiterate notions of Americana, but the cumulative effect was dizzying—an incongruous amalgamation of signifiers. (I am certain that many Japanese-style restaurants in America feel just as insane to the Japanese.) I nibbled a French fry. There were license plates from Illinois and Montana hung above my table.

I’d made arrangements to meet up with the expat writer Michael Pronko, who was born in Kansas City but has lived in Tokyo for the past fifteen years, teaching American literature, culture, film, music, and art at Meiji Gakuin University. Pronko writes and edits for a website called Jazz in Japan, which features reviews, interviews, and essays about Western music in Asia. I eventually found him waiting outside the Shimokitazawa subway station, wearing the hat, glasses, and beard of a man who has traveled extensively—the grizzled-yet-refined comportment of a war correspondent. We repaired to a bar.

I figured Pronko might have ideas about why American blues resonates so strongly for some Japanese audiences. I already knew the rote sociohistorical explanation—how African-American soldiers stationed in Japan during and after World War II had brought their record collections with them, and how an appreciation for those sounds (which were unfamiliar and, for many Japanese listeners, intoxicating) took root, flourished. This, of course, is also the story of every musical diaspora: a song or style travels, via commercially pressed records or sheet music or radio broadcasts or the performers themselves, and we are reminded anew that art transcends geography and that some expressions are so universally human as to be undeniable.

I was curious, though, about how this particular transmigration might be more complicated; blues, after all, is especially indebted to its place of provenance (the Deep South—specifically northwestern Mississippi and parts of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas). To my ears, it is the most essentially American of all the great American idioms, and contains a more literal retelling of its originating landscape than any other genre I can think of—there is a saturation and a heaviness to early blues, a doused but crackling heat, a flatness. This is one reason blues tourism continues to flourish in the Mississippi Delta. Fans share a pervasive belief that this music is perhaps best deciphered by more closely examining its wellspring, by coming to know the earth there, by steering the family sedan to the so-called Devil’s Crossroads in Clarksdale, where Highways 61 and 49 intersect, and where, in the most apocryphal of all the great and concupiscent blues myths, Robert Johnson sold his soul to Satan so he could finger some hotter licks. Dazed-looking blues fans pull over, climb out of their cars, draw a lungful of soggy Southern air, and, maybe, unlock some part of themselves. I’ve done it, is all I’m saying—I’ve gone there looking for answers. I found some.

Pronko and I ordered a round of beers. My theories were rickety, but I charged ahead nonetheless. I asked him about what I understood as a compelling tension between Japanese humility—a pervasive, unwavering stoicism—and the more unfettered spirit of the blues. These were grand, maybe irresponsible generalizations, but even despite my broad strokes, a disconnection felt palpable. “Blues is raw. There’s no filter—[blues musicians] are often saying that they’re angry, they’re depressed,” Pronko agreed. “In Japanese culture, you tend to not express those things. To say, ‘Oh, I feel terrible’ is a burden on the other person, because then they’re obligated to listen to you and take care of you. It’s the same in America, maybe, but that obligation is stronger here,” he continued. “When I play blues to students, I tell them to not listen to the words, but to listen to the feeling of it—to the gut-punch. Do that first, then we’ll get into the words. I think that kind of direct, emotional, uninhibited expression is really appealing to the Japanese, because things are so restrained in Japanese society.”

We finished our beers and eventually made our way to Lown, climbing a couple flights of stairs (Tokyo, unlike most American cities, uses its vertical space in multi-purpose ways; storefronts aren’t only at street-level) into what appeared to be a small living room with a well-stocked bar. “This is what’s called a Live House,” Pronko said. “Musicians rent it, or make a deal with the owners to play here.” He’d mentioned earlier that he was often the only non-Japanese person in the audience at a blues show; watching the crowd gather, I understood what he meant. Pronko introduced me to Samm Bennett, another expat—Bennett was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama—now working in Tokyo as a musician. We took seats along the back wall, in part because we were some of the tallest people in the room.

Steve Gardner was scheduled to play second. He was preceded by a folk duo called Magic Marmalade, who sang a beguiling acoustic song about a cactus named Linda (according to my notes, it included the lyric “Let us merge in the cosmic dance”). After their set, Gardner—a kind and jocular man, wearing jeans, suspenders, and a white porkpie hat—made his way through the crowd and toward the stage, carrying a National steel guitar. His voice is bulbous, rough, loud—equal parts Sam Elliott and Charley Patton. He pulled out a glass slide and opened with a rollicking version of “Shady Grove,” a traditional Appalachian folk song.

Gardner is a natural raconteur, and the crowd absorbed his banter readily. “There really wasn’t any blues until they figured out a way to sell it. Before it was recorded it was just music, and that’s really how it oughta be, you know?” Gardner paused, worked out a few licks. “Lots of great music was recorded by folks who couldn’t see too well. A man named Blind Blake made this song, and I really do like it,” he offered. “It’s an old-time tune called ‘Police Dog Blues.’”

“Police Dog Blues” was recorded in Richmond, Indiana, on August 17, 1929, for Paramount Records, a chair-company-turned-record-label based in Grafton, Wisconsin. Not a whole lot is known about Blake’s life: he was born blind in 1896 in Newport News, Virginia, but also lived in Jacksonville, Florida, and parts of Georgia (it has been suggested that he sometimes spoke in a Geechee dialect, indicating that he may have spent time in the Georgia Sea Islands). He began recording for Paramount in 1926 and made around eighty 78 rpm sides for the company; for a prewar country-blues performer, he was remarkably prolific, which means he was also commercially successful. “Police Dog Blues” is a song at least nominally about knowing when to give up on love. “All my life I’ve been a traveling man,” Blake sings in his sweet, lapping voice, fingerpicking his guitar. “I ship my trunk down to Tennessee, hard to tell about a man like me.”

Gardner’s take was bigger, more spastic. “I met a gal, I couldn’t get her off my mind,” he hollered; there was real desperation in his voice. Hearing it played this way, on the outskirts of Tokyo, sipping a sweating glass of Kentucky bourbon in a room full of rapt Japanese blues fans—it was spiritually rattling. According to my papers, I took only one tired, inscrutable note: “This shit, same old shit, always the same.” The way things move. What makes us human.

When you are an American plotting your first trip to Tokyo and canvassing your network for tips, you will be told that the city is inscrutable to outsiders, and especially to Westerners. You will wonder if your colleagues are being hysterical when they say things like, “The streets don’t have names,” or, “There’s a beautiful club, but I couldn’t possibly tell you how to find it.”

It turns out that the Japanese addressing system is famously idiosyncratic. Tokyo is chockablock with tendrillar, lantern-lit alleyways that seem to circle in perpetuity—thousands of spiraling paths to God-knows-where. Street addresses, on the occasion that they are transcribed in Latin characters, tend to resemble lock combinations, like 2-10-305; this is technically the district, followed by the city block, followed by the house number, followed by a fourth number if your destination is an apartment. In Tokyo’s more obscure pockets, the buildings are not numbered consecutively (so ten might very well precede six). Even locals reference landmarks exclusively when attempting to offer a forgeable path. Like, “Exit the Shibuya Station, take a left when you see three izakaya in a row, take four more rights, take two quick lefts, walk up a steep hill, turn around, find the alleyway, look for a building with a snake in a terrarium in the window, then go to the third floor and knock a couple times—knock pretty hard.”

If you start searching the Internet for help, thinking you are a real crackerjack reporter, you will end up on pages with titles such as, “The Black Art of Finding a Japanese Address” or—and this is in the New York Times—“Tokyo, Where Streets Are Noodles.” That piece includes a telling exchange in which the writer implores a shop owner to divulge some tips. Was there some furtive trick nonlocals could use to navigate the city?

“‘No,’ said the owner, who declined to give his name. ‘You have to just walk around, and that’s the best way.’”

I spent much of my time in Tokyo—eight days in late July—feeling glad but disquieted, perplexed. I am loath to recount any of this, because of course this is precisely how the narrative is always written: an American is set loose in Japan, and she is immediately adrift, rattled, roaming the streets in a kind of bewildered, lonesome daze. The bellwether of this particular canon (and it is staggeringly populous) is Sofia Coppola’s 2003 film Lost in Translation, which recounts the odd, poignant relationship between Charlotte, a recent college graduate, and Bob, a waning film actor, as they wander Tokyo’s opulent and hermetic Park Hyatt hotel, only periodically venturing beyond it. They are both searching intensely for something they can’t, or don’t feel ready to, name.

Charlotte (played by Scarlett Johansson) is in Japan with her husband, a celebrity photographer on assignment; Bob (played by Bill Murray) is filming a series of commercials for Suntory whiskey (“For relaxing times . . . make it Suntory time!”). It’s a beautiful and poetic film about yearning—or at least about reckoning with your own emptiness. It is also a movie about being tired, both literally—there’s at least a thirteen-hour time difference between the east coast of the United States and Japan, meaning the day is rendered fully upside-down, a flipped hourglass—and in more metaphysical ways.

The writer Joe Wood, in the opening paragraphs of his 1997 essay “The Yellow Negro,” about Japan’s relationship to black culture, describes “a sense of isolation” fastening to his brain “like a lump of ice” upon his arrival in Tokyo from New York. I could see how Japan might be a place Americans travel not merely to put distance between themselves and their regular lives, but to render those lives incomprehensible; how, if your very existence has started to feel foreign to you, a satisfying solution might be to go to a place where your life is actually unrecognizable, to make real what you already know in your bones. This could account for the feelings of dissociation and loneliness that so often haunt these stories.

But surely there’s also something about Tokyo’s sheer size—thirteen and a half million people living within the city limits, and thirty-eight and a half million within the region, making it the world’s most populous metropolitan area—that inevitably reminds a person her life is merely one of many lives, a realization that sounds banal, even stupid, but can still trigger a funny kind of existential spiral. Then there’s Japan’s particular insularity: it’s an island nation, culturally homogenous (at last count, in 2010, its population was 98.7 percent Japanese), and often wary of outsiders, or gaijin. Wandering Tokyo, I found it nearly impossible not to be continually reminded that I was a foreigner.

Ergo, that tourist’s glaze: you are exhausted, and instantly recognizable as an interloper, and counting buildings, and walking great and hilarious lengths in the exact wrong direction, and acclimating poorly to the humidity, and bewildered by the language, and feeling sensitive about your life relative to every other life, and, somehow, in that confusion, a kind of cognitive dissociation occurs. A fissure. What emerges from that space is different for everyone. The film critic Elvis Mitchell wrote that Lost in Translation suggests “a moment of evanescence that fades before the participants’ eyes.” Many Western recollections of Tokyo share a similar vestigial quality: it is incomprehensible, liminal, hazy. And then it is gone.

Later that night, after his set, Gardner walked me toward the subway station and repeated the best way back to my accommodations. I suspect he saw on my face that I was the type of exhausted in which new information doesn’t register quickly, or well. After he turned to go back to the club, I encountered an ordinary-looking Japanese man in a dark gray t-shirt, maybe nineteen or twenty years old, with his back to the street. There wasn’t anyone else around; he was standing behind a leafy bush, near a closed grocery store. He’d huddled himself against the side of the building. An acoustic guitar hung from his neck by a length of rope. He was hunched over it, bent a little in the middle, playing a rollicking country-blues lick over and over and over again.

It was such a strange and private moment. I felt like I probably wasn’t supposed to be there; I still don’t know if he knew that I was. His playing was beautiful: sloppy and hot. Gleaming commuter trains passed overhead, reflecting in the storefront window, rumbling up to speed. I held my breath and took a nine-second video with my cell phone. This is the only reason I am certain that this happened.

A couple weeks after I returned to the U.S., Pronko shared some of his students’ writings on the blues singer Bessie Smith, with hopes that their pieces might further resolve some of my questions. Although his students were still learning English, I found their written reactions moving, trenchant. One, responding to Smith’s fleshy “Do Your Duty,” from her final recording session, in New York in 1933, admitted: “In this song, she says ‘Do! Do! Do!’ to her man. If I were her, I can not say because of shameful things. But she say all things what she wants directly to her man with no shame so she is very cool. And these songs of Bessie Smith tell me or us it is OK to be so selfish so I was given courage after listening and studying these songs.”

Before arriving in Tokyo, I’d read about the Japanese phenomenon of karoshi, or death by overworking. In 2008, the Washington Post reported on Japan’s so-called “killer work ethic,” explaining how “overtime rules remain so nebulous and so weakly enforced that the United Nations’ International Labor Organization has described Japan as a country with no legal limits on the practice.” It’s not especially unusual for a salaryman—as white-collar corporate workers are known here—to very suddenly collapse and die, usually after suffering some type of cardiac event, or via self-inflicted wound. Suicide is presently the leading cause of death for men aged twenty to forty-four in Japan, and it is not thought of as a particularly dishonorable or shameful way to die. (Kamikaze pilots, who led suicide attacks on Allied naval vessels, are still understood as heroic figures; this might be in part because the country has little history of Christianity, which declares suicide a sin.)

Pronko said he’d noticed the way Japanese salarymen seem to transform when they listen to music. “Get me out of my thoughts, my obsession with work, and move me into some human experience,” he said. “Let me stop thinking about this bullshit, and start being a person.”

The idea of a deliberately concealed or shifting identity is essential to Japanese cultural history: Noh, which peaked sometime in the mid-1300s, and Kabuki, which began in the early 1600s, are two theatrical traditions that hinge upon the transformative and sometimes bewildering power of a literal mask (or, at least, very heavy makeup). Masks, whether actual or metaphoric, are omnipresent here. “You can see a Japanese person visibly relax when they step into a club,” Pronko continued. “It’s a sacred space in that way. In the States, you also go to hear music to stop your brain, to be different for a while. But it’s less explicit, because the pressure is less—you can be a human being at work in America. You can’t always in Japan. You’re at work and whoever you are is kept inside so you can work. In the States, you’re who you are. You’re a nice person, you’re an asshole—you’re the same at work.”

Was there something inherent to blues music that might facilitate this kind of loosening? It’s a reductive distillation, but if you consider the challenge of Japanese work culture alongside the challenge of being a blues singer in the first few decades of the twentieth century (affluence versus impoverishment, marginalization), the conditions can seem at odds, incompatible. Still, I suspect that unhappiness itself—however it is borne—becomes a kind of password. It transcends its origins. The blues isn’t always sorrowful, but it is usually wanting.

It seems possible to argue that American blues offers a new solution to the Japanese, an idea they maybe hadn’t encountered before, hadn’t realized could work as a balm. It’s not merely a reflection of ennui or despair or confusion, it’s a deep validation of it. It externalizes the internal in a way that allows for catharsis.

But it’s not a universal panacea. Pronko said that sometimes, in his experience, blues music is just too inexplicable for a Japanese listener to really connect to. “It’s a nonformalized experience,” he said. Such things are rare in Japan. “You don’t know what’s gonna happen; you don’t always know how the song is gonna turn out.” Pronko told me that improvisation, as a concept, is novel to his students (I resisted a joke about my own university students, so beautifully capable of spontaneously inventing whole, operatic responses to books they have not read). “It just doesn’t translate. I have to explain it. Just the idea of not following the notes, not even looking at the notes, not even having notes to look at—it blows their minds. What do you mean, he’s just playing it?”

I’d been told a good place to see Japanese musicians playing blues was a club called Blue Heat, in the Yotsuya neighborhood of central Tokyo. When I pulled up in a taxi, around 9 P.M., I saw its big, glowing sign first: LIVE AND BLACK MUSIC BAR BLUE HEAT. When I went inside the building, there was a canary-yellow sticker reading “Real Black Music!!” affixed to its mailbox.

Judging by the signs dividing up the record bins in Tokyo, “black music” is a genre unto itself in Japan, and it encompasses hip-hop, r&b, gospel, soul, funk, blues, and jazz. (This bracketing phenomenon called to mind, for me, the scene in This Is Spinal Tap in which David and Nigel, recounting the spontaneous combustion of their drummer, bicker lightly about whether the festival they were playing was a “jazz-blues festival” or “a blues-jazz festival, really.”) That these are very distinct traditions in America seemed somewhat irrelevant here, perhaps in part because Japan has so few black citizens.

The national census doesn’t inquire about race or ethnicity, merely nationality, so it remains difficult to find precise numbers about the country’s racial makeup. (In my brief time exploring Tokyo, I somehow saw just one black person: the recording artist Ben Harper, strolling through a park with a companion.) In 2015, a half-Japanese, half-American couple—Rachel and Jun Yoshizuki—made a YouTube documentary, Black in Japan, exploring the experience via interviews with seven African Americans and one Jamaican living here. Their subjects’ impressions are largely positive, though they do recount being photographed without permission, having their hair touched by strangers, and being called “Whitney Houston.” Most said they still felt safer in Japan than in America.

Joe Wood, wandering the streets near Tokyo’s Shinjuku Station, met a more unwelcome gaze. “I thought I could detect an ugly fascination in the eyes of the people around me,” he writes in “The Yellow Negro.” “How bizarre that there should be such malevolence toward blacks in a country with almost no black people.” Wood discusses his fear of encountering Sambo, the contentious title character from The Story of Little Black Sambo, a children’s book written and illustrated by the Scottish author Helen Bannerman in 1899, and featuring a young, dark-skinned boy with hugely exaggerated features; until recently, Sambo iconography remained oddly popular in Japan. In 1932, Langston Hughes described the book as “amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word to one who has known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being laughed at.”

The problem with trying to mindfully unpack Japan’s blues fandom is that even the most expansive theories require condensing whole cultures—to say nothing of individual tastes—into representative sums. Occasionally, those sums feel like dangerous projections. In his essay “The White Negro,” Norman Mailer argues that Beat writers were drawn to and impressed by jazz and blues because the players “gave voice to the character and quality of [the musician’s] existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream, and despair of his orgasm.” Through that, they could achieve a kind of proxy freedom, a rejection of what they understood whiteness to be: a buttoned-up, suburban lifestyle in which emotion was stifled or politely presented, rather than loosed and celebrated. This, obviously, is a preposterous and troubling fantasy, hinging on, among other things, the presumption that black Americans are free of inhibitions, unattached, hypersexual, primitive, and inherently better at expressing bodily anguish or ecstasy.

The idea of being attracted to something by virtue of its exoticism has been nothing but trouble, historically (the Japanese themselves have been subject to this for centuries; the social justice activist Andrea Smith once named Orientalism one of the “three pillars of white supremacy”). But because Japanese culture is so insular, and because there are so few other races established here, it seems likely that Japanese music fans might have come to regard American blues musicians—most of whom were indigent, and nearly all of whom were black—as curiosities.

Still, as far as I could tell—and because of the language barrier, many of my conversations with actual Japanese blues fans were mimed interactions; this is not the most sophisticated way to communicate multiform ideas about anything, let alone the blues diaspora—the Japanese are interested in blues and jazz less for their strangeness and more for their complexity. For a non-native English speaker, blues, with its endless idioms and idiosyncrasies, requires work to understand. It demands studiousness.

“Japanese see blues as being this really difficult form to master,” Pronko told me. “It’s hard to play it well, and singing it is even more challenging. I think they respect it for the complex music that it is. The racial aspect is nearly secondary,” he said. The blues, then, becomes a daunting intellectual challenge. “A lot of bands here are called

‘copy bands’—they’ll play the Allman Brothers, or Stevie Ray Vaughan, or the Meters. These are bands that just work on capturing the sound of their particular band. From an American point of view, it seems false—‘copy’ sounds bad in America. But it doesn’t have that feeling here,” he continued. “To play a Stevie Ray Vaughan song well—that’s not so easy! To play well in an imitative way, it isn’t a shameful thing at all. There’s no hesitation to be like somebody.” This helps explain, in part, why karaoke—a Japanese creation—remains so wildly popular in Japan. In the States, cover bands (and karaoke parlors) are certainly present, but that American drive for true, seismic innovation—that frontier spirit, that deep thirst for ownership, the desire to venture where no one has gone before and claim a plot in your name—is paramount.

At Blue Heat, both the crowd and the band were exclusively Japanese. The audience was younger than I’d been expecting: couples who appeared to be in their late twenties or early thirties, crowded around long tables, smiling, smoking, clinking bottles of beer. The men wore skinny ties, and the women were in fashionable dresses and boots. The band, a four-piece—two acoustic guitars, an electric bass, and drums—was called Sweet Bitter Blues, which I only know from the half-English sign I saw posted by the entrance (the same sign also identified the guitarist and lead vocalist’s name as “Blues’n Curtain,” though no other players were ID’d in English). The interior was painted a dull black, and fading posters taped on the walls commemorated blues events of yesteryear. Otis Rush in 1966; the James Cotton Band. There were many shelves of vinyl records.

I took a seat at the bar. After a little banter in Japanese, and titters from the crowd, the band launched into Ray Charles’s “Hallelujah I Love Her So,” a gospel hymn Charles adapted and released in 1956 (it was later covered by Jerry Lee Lewis, Harry Belafonte, Frank Sinatra, and, most famously, the Beatles). Their set was composed mostly of covers. Hearing Allen Toussaint’s “Play Something Sweet (Brickyard Blues),” a hit for Three Dog Night in 1974, sung enthusiastically and in a very strong Japanese accent while an approving crowd claps along, is, I can say now with certainty, a singular musical experience. Blues’n Curtain was wearing a vintage Louisville Cardinals t-shirt and a busker’s cap. His performance was jubilant.

After the show, I stopped for a nightcap in Tokyo’s Golden Gai district, a corner of the Shinjuku neighborhood known for its clustering of tiny bars—six narrow alleyways, some of which barely allow for a whole person to pass through, leading to more than two hundred ramshackle taverns, most containing fewer than a dozen seats. I wandered into a place called Slow Hand, in part because its sign read EVERY DAY I HAVE THE BLUES.

“Oh, buddy,” I murmured to no one in particular.

Inside, I surveyed the ephemera: posters for The Blues Brothers, Eric Clapton, the Butterfield Blues Band, Frank Zappa. A giant, curling portrait of Robert Johnson. I was the only patron. I ordered a Japanese whiskey, which arrived in a heavy, cut-crystal glass. The bartender—and lone employee—set out an ashtray decorated with peace signs and the words HAIGHT-ASHBURY, and began fixing me an octopus and miso salad, although I hadn’t asked for anything to eat. We tried to chat, but mostly we mimed, laughed. He told me a confusing but nonetheless thrilling story about John Mayer and Katy Perry coming in and ordering a bunch of drinks. The punchline was either “Suntory!” or “Katy Perry!” I inexpertly poked at a chunk of octopus with a chopstick. He put on a DVD of Blues Masters, a CBC documentary about a three-day recording session, held in Toronto, in 1966, that included Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, and James Cotton. He said his favorite piano player was Sunnyland Slim, who was born in the Delta but moved to Chicago in 1942, part of the Great Migration of black Southern workers to the industrialized north.

Eventually, he pulled out a ukulele from under the bar and played me a heartbreaking if imperfect version of “What a Wonderful World.” I tried to pretend that some dust had gotten in my eyes.

I’d arranged to meet Samm Bennett in the late afternoon, outside the Shibuya Station. He’d suggested that I wait for him near a bronze statue of an Akita dog named Hachikō. In 1925, a University of Tokyo professor named Hidesaburō Ueno suffered a fatal cerebral hemorrhage in his office. But Hachikō, his steadfast pet, had continued waiting outside the train station for his owner to return home, keeping up the routine for the next nine years, nine months, and fifteen days, before dying himself, of a terminal cancer, on a nearby street. Hachikō is now a folk hero—a symbol of unwavering faithfulness and loyalty. His body was cremated and buried alongside Ueno’s, and his pelt was stuffed and mounted; he remains on permanent display at the National Science Museum of Japan. In 1994, producers from Nippon Cultural Broadcasting somehow came across an audio recording of Hachikō barking, and fifty-nine years after his death, millions of Japanese reportedly tuned in to hear him on the radio.

Hachikō’s popularity is unsurprising, insofar as he embodies two crucial aspects of Japanese culture: he is selfless, and he is adorable. Much has been made of the Japanese preoccupation with cuteness, or kawaii, in which sweet, childlike, and non-threatening things are revered, from small plastic ice cream cones to pink baby-doll dresses to Hello Kitty sex toys. Once, during a thunderstorm, I panicked and took accidental refuge in a store called BABY LOVE, which sold only tiny live animals: kittens and puppies that looked as if they were born mere days ago, snoozing away in little Plexiglas boxes. Of course, I briefly lost my mind—am I not human?—but I did eventually blanch thinking about what might happen when these guys turned a month (or more) old. Infancy, after all, is an impermanent condition.

Bennett and I sat down at the only nearby bar that was open, a British-style pub, and ordered Bloody Marys. Michelle Branch’s “All You Wanted” was playing on the house stereo. Bennett was born in Alabama and weaned on the Allman Brothers, the Beatles. “I grew up in a middle-class suburb. It’s not like there were bluesmen on the corner,” he said, laughing.

In 1995, he moved to Tokyo from New York City, exclusively to play music—jazz, blues, and his own experimental reworkings of both. “I first came here to play concerts in 1986. There was a connection between the downtown New York scene and certain Japanese musicians, and I got invited over to do some shows. After that, I came to Japan about once a year, almost always with a saxophonist named Umezo Kazutoki. We were doing free improvisation—not an extremely austere thing, we did a lot of grooves. The term ‘jam band’ didn’t exist back then, but we were kind of a jam band.”

Bennett was understandably reluctant to make generalizations about why blues remains popular in Japan, but he did acknowledge a gulf. “I think a lot actually gets lost in translation. Really liking something and really ‘understanding’ it are two different things,” he said. “People really love the blues here. That doesn’t mean that they’re catching all the inflections. When Japanese people play the blues themselves—and I hesitate to say this—there’s something almost grafted on. It’s not something that’s entirely . . .” He paused. “The word ‘natural’ is really loaded—everybody has to learn. But the really good players master certain styles instrumentally. Vocally, it’s another thing. Blues, in particular, demands a certain kind of character. Even the best jazz singers aren’t that great when they sing the blues. I think it’s a question of feel.”

After Bennett split to prepare for Drunk Poets See God, the monthly English-language poetry and music show he hosts, I took the train to Nakano City, a ward west of Tokyo proper. I’d been told there was a blues club there called Bright Brown, a kind of epicenter of the scene. I wandered the neighborhood for a while, eating conveyor-belt sushi, drinking cups of sake, popping into izakaya. I tried my luck at one of those bleeping, apocalyptically lit arcades full of claw machines, attempting to fish out (in order): a giant stuffed cat, a giant stuffed banana, a small stuffed donut, and something that looked like an overfed gerbil. I left empty-handed.

By the time I found Bright Brown—this involved walking past it approximately thirty-five times—a Chicago-style blues guitarist named Hurricane Yukawa had just taken the stage. I tried to linger inconspicuously in the back, but a barkeep emerged and kindly led me to an open seat at a table full of young Japanese folks, who immediately offered me the plates of tomato salad and cheese and crackers they’d been sharing. There were framed pictures of American bluesmen on the wall, and a small disco ball hung from the ceiling; the room was warm and crowded and lit by strings of white Christmas lights. I ordered a whiskey.

Yukawa was playing with a pianist, a Japanese woman in a white t-shirt and black jeans who didn’t seem much older than thirty. Her hands appeared to be moving fully independent of the rest of her body—this is the case with all the best blues pianists—her fingers levitating over the keys and then striking suddenly, fiercely, like a snake winding through tall grass. Yukawa was playing a Fender Telecaster and expertly running through the postwar Chicago blues songbook—“Pitch a Boogie Woogie If It Takes Me All Night Long,” the Howlin’ Wolf catalogue. He had slicked-back hair and a generously unbuttoned shirt. Between songs, Yukawa bantered amiably with the audience. The spirit was jovial, easy. During a break in the set, I had what felt like a fairly sophisticated conversation about Rolling Stone magazine with a man wearing a loosened tie, though the only words either of us actually said were “Rolling” and “Stone.” At one point, another of my tablemates, who had seen me scribbling in a notebook, pointed at me and yelled, “American writer!”

Everyone laughed hysterically.

Enjoy this story? Find more blues writing in the 2016 Southern Music Issue: Visions of the Blues and subscribe to the Oxford American.