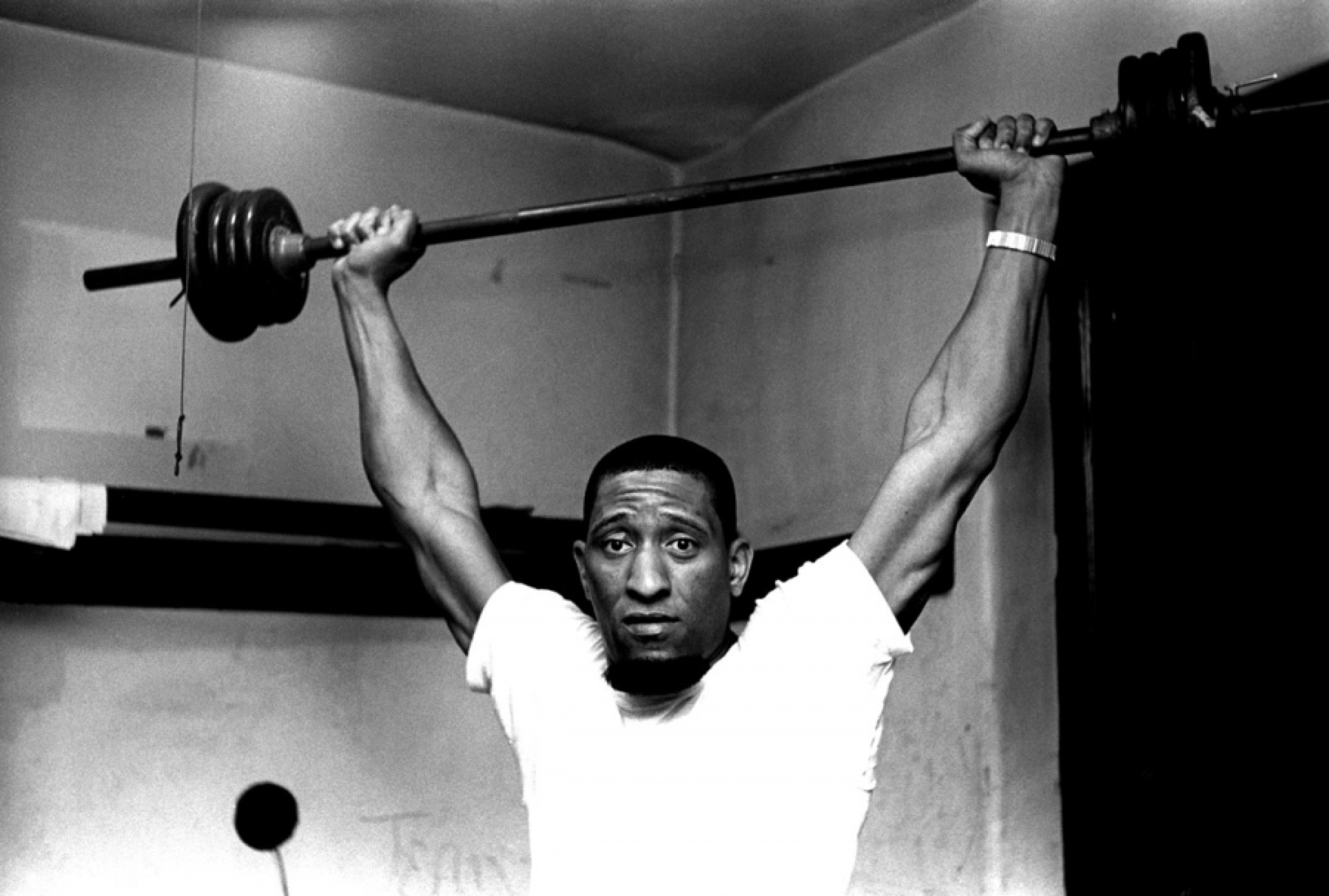

Photo of Sonny Rollins courtesy of Steve Schapiro / Corbis Premium Historical / Getty Images

The Lexington Cure

By Rebecca Gayle Howell

In Lexington, where I’m from, a federal medical prison stands on the town’s west side. Far off the main road, it does not ask our attention as we drive home from the Kroger’s or Goodwill—another sight among many in our urban pastoral. Not so long ago, this building held the nation’s attention as the world’s leading drug rehabilitation center, constructed to save civilization from the addict, and the addict from himself. Though, if the United States Narcotic Farm is today known for anything other than its eventual failure, it’s for the legendary figures who came there. Alongside average, nameless men recovered the likes of Sammy Davis Jr., William S. Burroughs, William S. Burroughs Jr., Clarence Cooper Jr., Barney Ross—and then there were the jazz musicians: Sonny Rollins, Tadd Dameron, Jackie McLean, Chet Baker, Sam Rivers, Wilbur Ware, Bill Caffey, Sonny Stitt, Red Rodney, Peter Littman, Elvin Jones, Ray Charles, Lee Morgan. The list is dizzying.

Patients, as they all were called, could arrive as incarcerated felons or check themselves in to take the Lexington Cure. Invoking a kind of Jeffersonian modernism, the Cure insisted a soul’s sobriety is what was needed, that a junkie must be healed from the spirit out. The doctors prescribed fresh air, and so the United States Narcotic Farm was indeed a farm—a thousand-acre self-sustaining community, right down to the milk it served. Honest work was to be learned and enjoyed as therapy. Other than farming, patients were given the opportunity to acquire skills such as auto repair and woodworking—skills that could finance their lives on the outside, without crime. Honest play was also logged as therapy, and among sports like baseball, tennis, softball, and bowling were chances to paint, dance, perform theater, and play music. Instruments were offered to the patients, and they were encouraged to practice nearly six hours a day. Soon enough, the doctors understood that, for an artist, practice is not leisure; it’s the only job that matters.

Although the presiding administration built Narco assuming its success, in only fifteen years the New York Times swung from announcing the institution’s messianic qualities to publishing its embarrassments, exposing that the treatment methods did not promote sobriety outside the prison’s walls. Ninety percent of patients returned. Though, it was only from one vantage that Narco failed; by the 1940s, from the addict’s perspective, Narco had become a one-stop network of professional users and criminals, the world’s best place to learn how to get higher.

Still yet, for the jazz musician, Narco became an elite artist’s workshop, a three-month retreat where hours of creative cross-pollination were sponsored by the federal government. Some checked in just so they could learn from the masters. Heroin helped an otherwise severely competitive stage of prodigies relax into their most concentrated Jungian state, that under-mind from which improvisation springs. But at Narco, competition for gigs vanished. The musician no longer needed to worry about food or housing or nightclub owners. All he had to do was arrange for his fix and endure his convalescence. Have an outsider visit you with a gift. Have an outsider throw a packet over the wall. Sleep, wake, eat, get what you need, and play.

Soon, a theater seating a thousand was made available for their purpose. Patients, nurses, doctors, and guards all came together on Saturday nights for the show. The town, too. These concerts, free and open to the public, made Narco the best underground night spot in Lexington. The phenomenon struck a chord with metropolitan jazz-heads and before long they began flying into our then hangar of an airport for a one-night fix of mind-altering music. History has called it “The Greatest Band You’ve Never Heard,” as all recordings, even the one made when Narco patients played Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, have been disregarded, destroyed, lost among the years.

Lexington has always had an unexpected bent toward the avant-garde. In these same years Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the now famously wild-eyed Southern gothic photographer, worked quietly among us as an optician in his little nondescript shop. His friend, the eminent peace activist and first hermit of the American Trappists, Thomas Merton, would catch a ride into town for parties, disguised as a tobacco farmer. James Herndon, known to us as Sweet Evening Breeze or Miss Sweets, was our churchgoing, cross-dressing neighbor, a landmark civil rights activist who today might have called herself black trans, who took an evening promenade through town daily, not only unafraid but celebrated, visiting with beloved friends who honked and waved as they passed. Rock Hudson was among the crowd, Bear Bryant, Henry Faulkner, as was my own father, playing on Coach Rupp’s JV basketball team, learning to drink at the old Saratoga, and earning a BA that he might enter the Marine Corps an officer.

So it is not a shock for me to imagine our 1940s, 1950s, 1960s barflies and college students, artists and athletes, driving out to the country for a big night at the prison. Merton was fever-sick for jazz. The only time I saw Dad happy was when he danced. Anyone might have been at Narco on a Saturday night, and I mean anyone—or: all of us, together.

Narco closed the year I was born. The nation that had hailed it as a “New Deal for the Addict” when it opened for business, by the early seventies could not enjoy more the emerging gothic stories of government-sanctioned drug experiments being carried out on Narco’s residents. Senator Edward Kennedy led the investigation while televised news sold the rumors to a people who’d turned a deaf ear to Tuskegee; a people still innocent of CIA-Contra but not above a sadist’s patriotism. Images of human subjects being made over in a likeness less than human—for the sake of the nation—gave the white middle class a story that offered all the allure of a neighborhood lynching.

These secret experiments, which chronicled the effects of certain drugs on the human brain, eventually became known as a larger operation called MK-ULTRA. In Lexington, the effort began after the war—a period of history that, without coincidence, aligned to the rise of white fear in urban areas and the incarcerated population’s ensuing revisions. The doctors offered commissaries of heroin from which residents could draw at any time, in exchange for full and willing contribution to the tests. LSD, ibogaine, psilocin, bufotenine—no, the patients did not know what they were being given. Yes, the CIA was involved.

By the time I was invited to spend a weekend on the inside as a leader of a Christian retreat, the government had rebranded Narco as the Federal Medical Center, and it sat on only a hundred of its original acreage, the rest made over into a city park and a housing development, all ensconced in strip malls. Still, from Narco’s long driveway I was hard-pressed to see anything but the structure itself. Wide, startlingly so, it filled my eye, the center tower entrance flanked by long halls that looked like the wings of a brick and limestone angel returning junkies to her womb.

Or, as William S. Burroughs Jr. wrote, it’s “solid, Jack.”

Art requires of its host a certain degree of separatism. In my own life, it wants as much time as I can give it, time my friends have invested in making money or raising children. To be a ventriloquist to the infinite, as someone like Sonny Rollins is, you’ve got to pay attention.

Poetry had come to me early on, in the form of popularized anthologies like The Best Loved Poems of the American People. I was a lonely child. Reading aloud those verses, all written by those long dead, I knew for the first time a shared song existed among people, that I was not alone. But I had no courage. While I did not ignore art’s entrance into my life, I was afraid of it. Dad would bring the books to me from the trips he took to receive his chemotherapy. Diagnosed at stage four, a few months after my mother finally filed for divorce, Dad was told by his doctor he had little time to live. Naturally, he got saved, began reading the Bible and James Michener, started shopping bookstores. He became, in short order, serious; he became a father.

The problem was that I’d been saved, too. Or, more: I’d joined the Church. A monotheistic God who is both all-knowing and peculiarly focused on loving you is a story that can change a person. Add to that a meet-and-greet of people who feel endowed to know whether you are earning that love, or, worse, to whom you feel you owe a profile of goodness, and a religion predisposed toward serving “the least of these,” rapidly and in a cascading series of complications too slight to track begins serving something else entirely.

In my teens, when the prosperity doctrine had married well to both Clintonian economics and James Dobson assholery, the evangelical subculture was succeeding, building traditional families one cross-decorated McMansion at a time. Pastors began wearing Madonna-headsets, and radio DJs sentenced anyone searching the dial to tin-can sanctified pop. My fifteen-, sixteen-, eighteen-year-old selves found it alluring, this system in which I could earn my keep, in which I could belong. No matter where I was in my day, it told me what kind of person to be, what the rules were. My parents were good parents. But in order for us to pass as middle class, they’d opened a diner and together worked sixteen-hour shifts, seven days a week, three hundred sixty-three days a year. Then, the divorce. Then, the cancer. A developing child needs mirroring to feel secure; the Church became my dealer.

Our retreat crew included a CFO of a major oil company; two Vietnam vets, one Tall, the other Short; and twenty-one-year-old me, the only woman. On our first shared morning at FMC, the men who’d volunteered for the retreat filed into the room, and the now expected and cruel racial demographics of those who live on the inside and those who live on the outside were tidily drawn. A guard gave the count, a requirement for any of our movements, then took his seat in the back. The residents left each other to find seats at the four round tables, at which one seat each was already taken by myself, the CFO, the two veterans. Here, we’d listen to talks and testimonies, break bread, pray, and hold hands. We were not allowed to ask why any of them were incarcerated, though a few offered up. At Short’s table, one old man said he’d robbed a bank. At the CFO’s table, another said he’d killed someone.

Killed someone. Why would he have told the truth? Why wouldn’t he have? What could a lie matter now, in these few hours we had, among his decided years. It was over, his crime; a long-ago story, a past, that either an authorized offender had told about him or he had enacted, set in motion, at the impulse of his own two hands. Likely, he was driving home to his family after a night shift, pulled over for a broken taillight. A few ounces of marijuana “found” under his seat. The thing is: only he knew. It was his story to tell.

What story did I have to tell? I didn’t want one. What I wanted was to disappear into other people’s stories. I entered that weekend a member of a certain spiritual economy, one in which I bartered my own liberty, my own truth and presence in this life, in exchange for a little company. At the time, it felt like a bargain, to barter my silence, which I anyway preferred. Silence is a convenience to the person who wants no responsibility. To tell one’s own story, no matter how wretched or mundane, has consequences. Evangelical Christianity taught me that if I acted righteous, I would be called righteous. Actual Christianity teaches me that no one is righteous, not one.

At my table a young, elegant man sat beside me, and when we prayed, he’d stroke the back of my hand with his thumb. We did not directly speak except once, when he told me he liked to listen to WRFL, a local college station. He asked if I’d ever heard this song, where a guy is playing the keys and singing slurred, The piano has been drinking, the piano has been drinking—

—Not me, not me, I finished. For an uninterrupted moment he and I, we saw each other. Then we looked away and laughed at denial’s joke.

For Saturday night’s final gesture, the CFO had arranged for forty or fifty local believers to come to the prison, stand outside the rec room, and lift lit candles into the dark and starless sky. What did it indicate? That the Church was larger than those walls? That these men were not forgotten? No. These men were forgotten. The federal government had seen to it.

Twenty years later, now that I have learned rather thoroughly I am unjustified, I can see the ceremony carried out that night, its power, its gift, amounted to one thing: showing up. When we heard the voices of those who stood outside singing, the residents and we looked out the windows to find them there, a mass of people who’d shown up for us, who’d tonight cared. The gift they shared was lasting because no false promise of tomorrow was made. There, on the other side of the glass, we stood struck still and sang with them. Then, some of us dry-eyed, others not, we lined up for the count and went our own ways.

Showing up. As I am. That’s what art wants of me. A banal, human devotion. When I decided I would not enter the ministry, but instead become who I was; when I entered, not the Church, but the studio of a local artist for whom I went to work, my friends thinned, and I spent my time increasingly in solitude. Alone again, as I had been when poetry first found me, I was now free to keep company with Rumi and W. S. Merwin, Amiri Baraka and Louise Glück, William Christenberry, Carolyn Forché, Wendell Berry, Tina Modotti, Nikky Finney. Through these artists’ books, I joined another assembly. One that was much more demanding, because it was liberating.

When Sonny Rollins crossed Narco’s door, he’d checked himself in. “I thought at first that [heroin] helped me focus on music,” Rollins told the Atlantic in 1999, “but then I realized it was a trick bag. Soon I didn’t even own a saxophone anymore. Guys I knew were crossing the street when they saw me coming. I was even stealing from my mother.” Rollins wanted to show his friend Charlie Parker, who’d urged him to get clean, that he could return to the music. But the music found him as he was, on the inside. In 1955 Rollins did four months in Lexington, and Parker died while Rollins was still in treatment. In 1956 Saxophone Colossus was born.

In 1958 Tadd Dameron took the Cure. There he led a band composed of fellow patients, including the great pianist Kenny Drew; the great saxophonist Sam Rivers; and the early white filcher of Miles Davis’s flow, Chet Baker. Baker would not become sober for another decade still (and it didn’t last), but after Lexington, as his biographer, James Gavin, notes, Baker grew suddenly into “a true jazz singer, capable of vocalizing with the flowing inventiveness of his best playing”—and the former crooner’s first scat was recorded the next year.

The year Sam Rivers walked out of Narco, he took up traveling with a thirteen-year-old Tony Williams and, together, they toured not nightclubs but art museums. Rivers told Michael Cuscuna, the founder of Mosaic Records, decades later:

The professor would stand by paintings by Van Gogh and others and explain the shape and movement of the brush strokes and other things about the painting, and we’d be playing the lines of the painting. That’s how I first became interested in free playing, from a classical point of view, abstraction, creating sound.

After Lexington, Rivers would become so wild in improvisation he challenged Miles Davis’s preference for modal technique and pushed the quartet into new heights during the tour that gave rise to the now much sought-after Miles in Tokyo recordings.

In 1963 entered Lee Morgan, who, after Narco, still on the nod, disappeared into the bathroom during a recording session and emerged holding scraps of toilet paper, on which was written a blues so dynamic he and his bandmates named the record after the new song. The Sidewinder would sell fast; Blue Note rushed to keep it pressed, and the record likely saved the label from economic ruin (even if it did not save Morgan).

The Narcotic Farm was a historic failure as a heroin rehabilitation center. But it seems to me a second, serendipitous Lexington Cure was offered there. For these artists—Morgan, Rivers, Dameron, Baker, Rollins, and how many others—this second cure revealed the way forward. As they moved in and out of Narco’s revolving door, an unimpeded exchange of talents, ideas, and techniques came and went with them. If jazz—born of work songs and blues, of sacred call-and-response, of sex and heroin and New Orleans, of bebop, of the Great Migration and racism’s brutalities and the strategies needed to survive it—if jazz is the one art form that can be truly called American, its revolution fittingly did not arise in New York, but rather at that Mason-Dixon crossroads: the Bluegrass Commonwealth.

Shortly after his time at Narco, Sonny Rollins took his first of two sabbaticals, as they have been called, times in which Rollins abandoned acclaim for practice. From the summer of 1959 to the fall of 1961, at the height of his world fame, he left the stage for the Williamsburg Bridge, where he practiced sixteen hours a day in the din of traffic. In 1968, he again walked away from his public to practice meditation in India. Whitney Balliett wrote for the New Yorker that Rollins’s sound upon his return had become a “whirlwind.”

In a recent interview with Tavis Smiley, Rollins remembered his time at the bridge:

I said, look. I’m going to do what I feel I have to do, which is to practice my horn. And get away, if that’s what I got to do, which is what I had to do. Just get away from the scene, completely. And do what something inside me tells me to do. That’s what I’m most proud of, Tavis. Of my whole life. That I did what something inside me told me to do. Regardless of what everybody was saying. “Oh, he’s great . . .” Bah. I have to know that.

This is the Lexington Cure I took that weekend at FMC, among the ghosts of Narco’s patients and among the living, incarcerated men who knew much about what it takes to get right with oneself. Since that moment I have tried, despite my own compulsory weaknesses, to build a life in which I might be saved by the grace of art, which is to say, by practice. The Church is a trick bag, but being born in a different time or place, I would have made a young career out of pleasing anyone who said they needed me to be pleasing. My father was dying. I had a hole in my heart. But before he went, he gave me two gifts that led me to the God of my own understanding. The first gift was poetry. The second, a love for jazz—born of his own, notably won among his young days in that formative, 1950s Lexington.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.