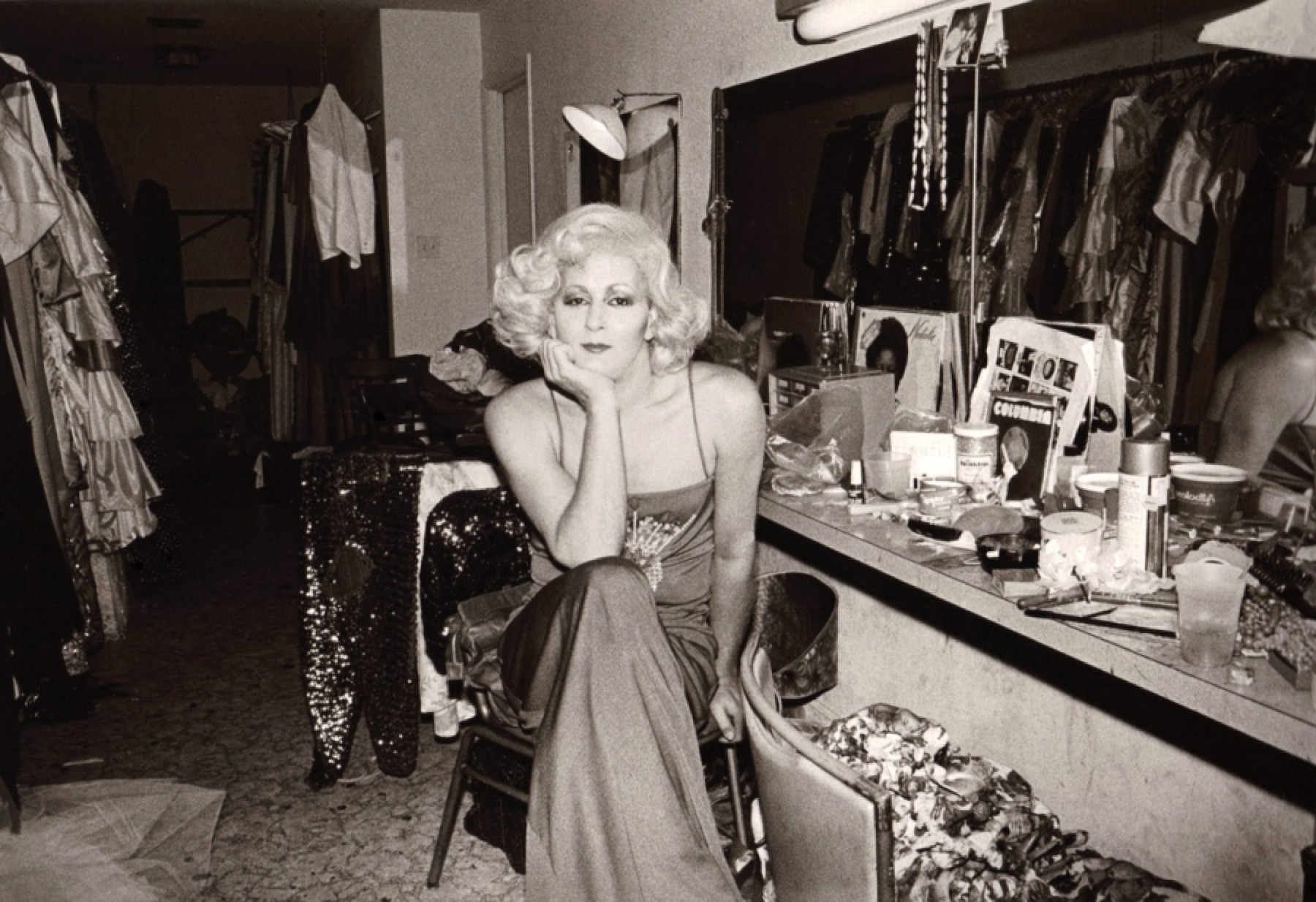

“Performer at Sweet Gum Head,” a photograph by Susan W. Raines. Courtesy the artist, susanrainesphotography.com

Underneath the Sweet Gum Tree

By Martin Padgett

In 1997 I lived a double life in Birmingham, Alabama. My gym had cruisy nooks and hours. Two women who tended a beautiful garden called my neighborhood home. Still, I believed coming out would come with unbearable consequences: I knew Alabama had no work protection for gay people. I knew I could lose my job just for being gay. So I arrowed east each weekend, sometimes at a hundred miles an hour, to Atlanta.

There, I went to my first gay bar—Hoedowns, on Cheshire Bridge Road, where good-looking men in cowboy hats whirled in line-dance formation. They glanced at me. I stared back at them. I smiled. I belonged.

Two decades before, on the same stretch of road, the dean of Atlanta gay nightlife had opened another country-and-western bar inside an old warehouse and made himself its sheriff. At the County Seat, Frank Powell built a replica of an old Wild West town, complete with wagon wheels, a country store, and a wishing well. And Frank didn’t own just one nightclub—he owned more than a dozen from the late 1960s until 1996, when he died of a heart attack. He opened quiet drinking bars, fancy fern bars, glamorous lesbian bars, hot disco bars, and seedy hustler bars. He named his most famous nightclub after his hometown in Florida. It was the “Showplace of the South,” the Sweet Gum Head.

Sweet gum trees, also known by their lyrical scientific name, Liquidambar, have hidden in their tall trunks a golden essence. They are natural healers. Their leaves can be packed in wounds, and the sap salves skin. The Cherokee chewed sweet gum sap to settle their stomachs; so did white settlers who drove the Cherokee from their home. Brewed as tea, the bark is a tonic for nerves. Hardy and strong, sweet gums grow in river bottoms and valley heads, across a swath of the United States that maps neatly to the South, with the exception of a few finger-like swaths of land that intrude into New Jersey and recede from Appalachia.

While hundreds of small Southern towns draw their names from native trees, mostly pines and oaks, the sweet gum tree has lent its name to just a few, including a tiny place in the Florida panhandle called Sweet Gum Head. Its namesake trees soar to more than a hundred feet tall along the loamy banks of Hurricane Creek.

In this thinly settled but fertile country, the land gave birth to bright yellow corn, deep orange peaches, and blue-purple plums, a rainbow that competed with the gum tree’s colorful fall leaves. The land also teemed with pine stands, where in the early 1900s lumbermen would slash virgin pines with wide blades to release the trees’ sticky rosin and boil it off into turpentine. Steamboats would churn northward on the Choctawhatchee River through earnest belches of soot to claim the bounty, then turn and float toward the crystal waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Yet the lumbermen left the useless sweet gums alone. The tree’s bark is rough like alligator skin, but it hides reddish satin-grain wood that warps easily and decays quickly. Sweet gum trees are soft at heart.

In 1931, James and Vallie Powell welcomed Louie Frank Powell, their fifth child, into a small, tightly knit community with a few dozen homes and a mail stop, but no theater or train station, not even a school.

“It’s not really a town,” Frank explained to a reporter from an Atlanta LGBTQ magazine in 1988, at the peak of the AIDS epidemic. He sat at a round table, near the end of the bar at The Conference Room, which he owned, his cheeks ruddy with drink and his small brown eyes sharp with memory. A photo of him dressed as Bette Davis hung on a wall nearby. The loosely organized community of Sweet Gum Head was, he recalled, “more like a curve in the road—twenty people, no red light, but it had a grocery store, and I decided to put it on the map.”

In Sweet Gum Head, Sunday church sing-alongs were one of the few forms of entertainment. The faithful came from miles around to hear preachers whip crowds into a penitent frenzy, and to open their hymnals and chime in during day-long seven-shape-note singing. They could sing along through the easy-to-learn method, which suppressed wayward voices by reducing their praise to a limited set of notes—do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti—each indicated by a distinct geometric shape.

At this open-air church, where worshippers were instructed to bring their hymnals and to pack a lunch for the long day outdoors, Frank learned that the Bible’s exact words were truth, that dancing and drinking were sins, that homosexuality was perversion, that evolution lied about the origins of man, and that segregation honored Christ. He took those lessons to school, miles away from home. He took them into his heart, when he did his chores on the family’s horse farm. He took them into the woods, where sometimes he would shirk his chores to wander and hide among the sweet gum trees.

Frank was good at hiding. Frank’s father and mother never knew he was gay, and other than his closest sister, no one else in the family did either. Some may have suspected when he enrolled at Bob Jones University, in far-off South Carolina, but homosexuality did not exist at the evangelist college, at least not officially. Frank coded himself and played the part of a righteous Christian soldier; he tamed his wavy brown hair, put on a sober blue blazer, and offered a thin smile for his freshman class photo.

After a year, he refused to go back to the school. His sister Pate says he never returned because he didn’t like it. He had plenty of reasons not to: Bob Jones’s form of religion was filled with hate and had taught Frank that he was sinful and wrong. Rather than return, he began a journey toward acceptance, like the one so many queer Southerners would make, a coming-out that would take him from the rural world he had known all his life to a place with a blank future, one ripe for imprint. He enlisted in the Air Force and left Sweet Gum Head for good, destined to become a different kind of zealot in a different kind of church.

Sweet gum trees bud late, but they make up for lost time. They set autumn fire to the South, torch it with orange and red and golden leaves, then shower the ground with spiky fruit. The heavily armored sweet gum balls protect their seeds through winter, then break open to let their offspring take wing.

Today, I venture proudly and safely into the straight world outside the confines of bars and clubs once designated specifically as “gay” spaces. I can be free. This wouldn’t have been the case a generation ago. Within my lifetime, queer behavior has put people in jail, in exile, and in danger. For many who faced their truth in the decade before Stonewall, often the only safe choice was to leave the small towns where they were shamed and muted and to run away to cities—though even in Atlanta, a town with well over a half million people in 1960, the year Frank arrived, gay bars were dangerous and illicit places. When he moved to Atlanta, Frank found a few places where gay men and women could discreetly discover each other, but it was no New York. It wasn’t even like Kansas City, where he moved after leaving Florida and learned the bar business at the Red Head Lounge, a place coded for its appeal to “particular people.”

A relatively progressive oasis surrounded by ultra-conservative mores, Atlanta didn’t yet have a single skyscraper in the early 1960s; it had onerous sodomy laws and a double standard where heterosexuals regularly “watched the submarine races” at Piedmont Park after dark while queers were harassed for walking there in daylight. Atlanta police once set up a two-way mirror in the men’s restrooms at the public library and arrested dozens for sodomy. Authorities would publish names in the paper, punish some with fines, even send them into exile.

Though other medieval rules applied—back then, Georgia outlawed any sexual intercourse outside of marriage—Atlanta still bloomed as a gay capital. It had a handful of bars that went discreetly gay after dark and a few risky drag shows. Frank skipped from bartending at Piccolo’s Lounge to managing the Joy Lounge, where he hired female impersonators who had to wear two pieces of men’s clothing or face arrest for disorderly conduct or for “masking,” a charge written into law during the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. When the police swooped in, drag queens would run and hide in the Joy Lounge’s cold storage.

Atlanta’s gay bars gave newly minted queers a place where they could mature in ways forbidden at home. They could meet same-sex partners; stumble through mating rituals like kissing and dating; expand their minds with LSD, speed, marijuana, or plain old alcohol; and learn their culture and skewer the outside world through the humor and satire of the city’s emerging drag scene. When Frank opened his first club, The Cove, he pushed the boundaries of what would be allowed; he brought in a DJ and allowed men to dance together.

“In 1968, if two women were seen walking down the street arm-in-arm, no one looked twice or thought anything about it,” he explained. “So why shouldn’t two young men be allowed to express affection in the same way?”

Atlanta’s queer bars remained underground places for a community that surfaced at night—until riots flared at New York’s seedy Stonewall Inn tavern in 1969. Stonewall electrified the growing queer nation, shattering its second-class-citizen status with bottles turned into missiles amid broken glass and fire. It channeled a potent cry for liberation and transformed it into a movement that spread to Atlanta; on August 5, 1969, city police raided a showing of Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys, took pictures of those in attendance, arrested the manager under local obscenity laws, and seized the print of the movie. They cornered one of the lesbian patrons and sneered: Where are your husbands?

The queer backlash only needed a nudge to ignite. The queers, hippies, and bikers that had formed a loose alliance on The Strip clashed with police near Club Centaur, where drag performer Phyllis Killer often sang in long blond curls, swinging an eighteen-foot feather boa as a jump rope and throwing lollipops to the audience. When police forced the Centaur to close, gays and lesbians staked out space within straight Atlanta at the annual Piedmont Park Arts Festival and handed out flyers. They formed a Gay Liberation Front, and some one hundred and twenty-five protestors turned up at 7th and Peachtree on June 27, 1971, for what would become Atlanta’s first Pride march. Denied a permit, they marched anyway on the sidewalks.

While the Gay Liberation Front cried out for public revolution, Frank set his sights on something quieter, but just as radical. Despite the threat of police raids, he wanted to open a show bar, one entirely dedicated to drag. His new club would challenge some of the city’s most strictly enforced codes. In late October 1971, he found the perfect home for it, on Cheshire Bridge Road in an old soul club. The fury of Stonewall had barely cooled; now Frank’s new nightclub would put drag queens on stage, six nights a week, right under the noses of the Atlanta police department. He already had a name in mind. He called it the Sweet Gum Head.

Sweet gum trees harbor a little-known talent: The seeds exude a chemical precursor for the psychedelic drug DMT. The “spirit molecule” inspires colorful hallucinations and life-altering experiences, even in minute doses. Users dub themselves psychonauts. They map uncharted territory in the mind. They explore the borders of self, space, and time.

On opening night at the Sweet Gum Head, the spotlight flared as Wendy Grape emceed, as Lavita Allen ripped into Streisand's “Hello Dolly!”, as Allison strutted through the same number in the style of Pearl Bailey. The club sat at the cruisy, electric nucleus of 1970s Atlanta, filled for a while by Frank’s hearty laugh. At the Sweet Gum Head, revelers streamed through a nearly anonymous entrance into a dingy old supper-club space, painted black and lined with red carpet, where a single mirror ball spun over the stage.

The Sweet Gum Head became one of the finest drag showcases in America. British Sterling brought her effortless diction and post-Motown miniskirt look to the Gum Head and brought home the crown in the 1971 Miss Gay Atlanta pageant. Frank’s good friend Danny Windsor applied his Hollywood expertise in leading his troupe to the stage; a former flying monkey in The Wizard of Oz, Windsor enforced a strict regimen of rehearsals on his crew of drag amateurs until they presented a polished, sensational presence.

“It was the first time drag had been done in this city with real production values,” Frank beamed.

Frank labored to keep the club quiet and to keep the police at bay, never putting up a sign, posting a watchman to signal when police circled and swung into the club’s parking lot, but the Sweet Gum Head had already given a home to rebels and freaks and outsiders of all genders, and the Cheshire Bridge strip had become a center of queer life. Inside the club, female impersonators perfected the radical art of drag while activists tried to enlist the night people into their revolution. They tried to raise a crowd to protest during Gay Pride Week in 1972, but Frank rebuffed them. “We don’t want any of that here,” he growled, and had them thrown out.

“Reputable gay people don’t carry signs in the streets,” he said. Rural life and evangelical roots had taught him to hide well. “I see those people on the news and they look like creatures out of a weird movie. I would never do that. I have nephews and nieces in this town, and I don’t want to embarrass them. They must know about me; I’ve opened thirteen bars here and every one has been gay as a goose. But I don’t have to flaunt it.”

I met my future husband just a few months after I moved to Atlanta. I hadn’t come out. We dated quietly, in moments stolen and moments made, in a gray space between old friends and new.

We visited a friend in the hospital, one evening in the months before protease inhibitors became widely available. He had contracted pneumonia. He lay in a bed in the hospital, spirits fine, prognosis mixed. When he was admitted, his T-cell count had fallen to 2. He dubbed those two T-cells “Itsy” and “Bitsy.” They were survivors; as for him, no one could be sure.

This is what being gay will be like, I warned myself, as if it were something I could change.

I spent a lifetime’s worth of panicked sleepless nights negotiating an existence between being true to myself and being frightened that my truth could drive my life away from me, one family member at a time, one T-cell at a time. The choices seemed horribly, asymmetrically unfair.

I chose life anyway. I had run away before, and running away had exhausted me and resolved nothing. I stood fast and brave. I survived.

Soon after I came out, I bought an old Art Deco–style apartment on a cautiously gentrifying stretch of Cheshire Bridge Road, next door to a strip club housed in a building that had once been home to the Sweet Gum Head.

Sweet gum trees band together and form dense cliques to survive. They are excellent at casting shade. They are pioneers that reclaim territory left behind by other trees.

With his Sweet Gum Head, Frank pioneered the seedy Cheshire Bridge drag strip. Other club owners joined him along a road which had become a Confederate soldier’s farm trail after the Cherokee were removed from it, where American soldiers bought tract homes after World War II on the GI Bill, where the new interstate carved a path for white flight to relieve its self-imposed anguish over progress.

Frank operated under the watchful eye of Atlanta Vice. In October 1972, he received a summons for a grand jury investigating organized crime in Atlanta’s nightclubs. When asked about the growing influence of organized crime in the city’s bar scene—in particular, in gay nightclubs—Frank professed ignorance. The inquiry fizzled, but in 1974 he sold the Cove and the Gum Head hastily, telling the city’s new gay newspaper that he needed a break from husbands and bars and showbiz. He left for a getaway on short notice and disappeared.

He lay dormant only a short time. Within a few months he resurfaced and opened the next of the more than a dozen queer clubs he owned over the next two decades, including the country-themed County Seat, where he reigned as the justice of the peace in his fictional Gay County.

“It was just like walking into a little town. It was a little world unto itself,” Frank said wistfully. “I wish that one were still around.”

While he started one new club after another, Frank never made himself a stranger at the Sweet Gum Head, which under new owners continued to host drag pageants and launch drag careers. It had acquired an edge that left him an outsider as it branched out into more esoteric forms of queer entertainment: the first Southern showing of John Waters’s Desperate Living, a convincingly cast production of Fortune and Men’s Eyes, and even a live sex show by blond-haired porn stud Jack Wrangler, then just beginning his relationship with quinquagenarian jazz muse Margaret Whiting. Atlanta drag legend Diamond Lil called the Gum Head her tabernacle; the club hosted Sunday shows with drag performers in religious garb, performing gospel favorites, even a full-on production of Jesus Christ Superstar. Frank visited often to judge drag pageants, tipple with managers, keep all his drag protégés close to him. He sat at a front table near the stage on August 30, 1981, when the Sweet Gum Head closed to the strains of performers singing “United We Stand,” just two months after the New York Times noted “a rare and often rapidly fatal form of cancer” that had already claimed the lives of eight gay men.

While AIDS ravaged the queer community, Frank took refuge at a succession of small bars he opened in Atlanta—at Frank Powell’s Place, at Plum Nelly and Plum Butch, and in 1980, at The Conference Room, a holy-looking venue with church pews lining the walls and songbooks from Sunday revivals promising salvation on the bookshelves in the corner. It was Frank’s own tabernacle. Though he had given up on Bob Jones University and evangelism, he never gave up religion, and he was eventually ordained as a minister.

Just fifteen years after opening the Sweet Gum Head, he came to look down on the Cheshire Bridge Road he had helped to create. “The neighborhood’s becoming what the Strip on 10th and Peachtree was: cheap, sleazy and all the other adjectives,” Frank said, aware that he had fathered it all, that it had sprung from his first acts of rebellion. Queer Atlanta could drink together because of him, and dance together because of him, and it was widely known that Atlanta visitors could find the best-looking hustlers at Frank’s clubs.

“That’s probably true,” he chuckled.

Sweet gum trees often stand in place of Dutch elms felled by disease, but they have ills of their own. Fungal infections mark dark brown lesions on bark. Dead tissue cankers. Branches fall. A plight called artist’s conk signals itself long after it infects the wood. Mushroom-like growths break alligator skin; the sweet gum dies from within.

History has given us sagas of world war, the Wild West, the suffragist movement, the civil rights movement. The queer experience has relatively little recorded history, in part because of the ravages of the AIDS epidemic. Those who died took their stories with them. Those who survived now struggle to remember what happened in the brief era between Stonewall and the epidemic.

The need to tell stories of the great gay awakening is more urgent today, as those survivors begin to fade along with the memories of their era of drag, drugs, and disco. It’s urgent, as assimilation has dulled a distinct dimension of the queer experience; we’re being straight-washed, just as an unashamed army of bigots wants to turn back the clock on progress. That progress is fragile and requires regular upkeep and maintenance and, occasionally, righteous anger.

Frank visited Florida on occasion, but he never went back to live there. A year before I moved to Atlanta, he died of a massive heart attack. His obituary places his death at his house near Ansley Park in Atlanta, but his sister believed he fell ill at one of his bars and died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. He is buried back home, hundreds of miles away from Atlanta, in a family plot at the Church of Christ Cemetery, at a bend in the road in the middle of nowhere in the Florida panhandle, where he rests by a sweet gum tree a hundred feet tall.

The town of Sweet Gum Head still exists, but it has no train station, no bus stop, no grocery store. Aside from a church and Ard’s Cricket Ranch, the town is hardly there, and hardly ever was. Though it exists mostly as a hazy recollection of a loose family of farms that dates back less than a century, it serves as a reminder that the queer history of America presents itself everywhere, even in the quiet, empty quarters of the South, where a January fog welcomes me as it clings to the steeple of the Sweet Gum Head Church of Christ. The grayness leaves dew on the granite graves of the Powell family and wraps a blanket around the hundreds of sweet gum balls that hang from nearby branches, ready to cast their seed far and wide. The trees can barely contain themselves in winter as their cycle begins anew. Soon they will burst to life in spring, and they will thrive in the strong spotlight of the summer sun. Their star-shaped leaves will trumpet the fall in a riot of color: crimson reds, glowing golds, vibrant pinks, deep purples, a rainbow.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.