Bitch Baby

By Halle Hill

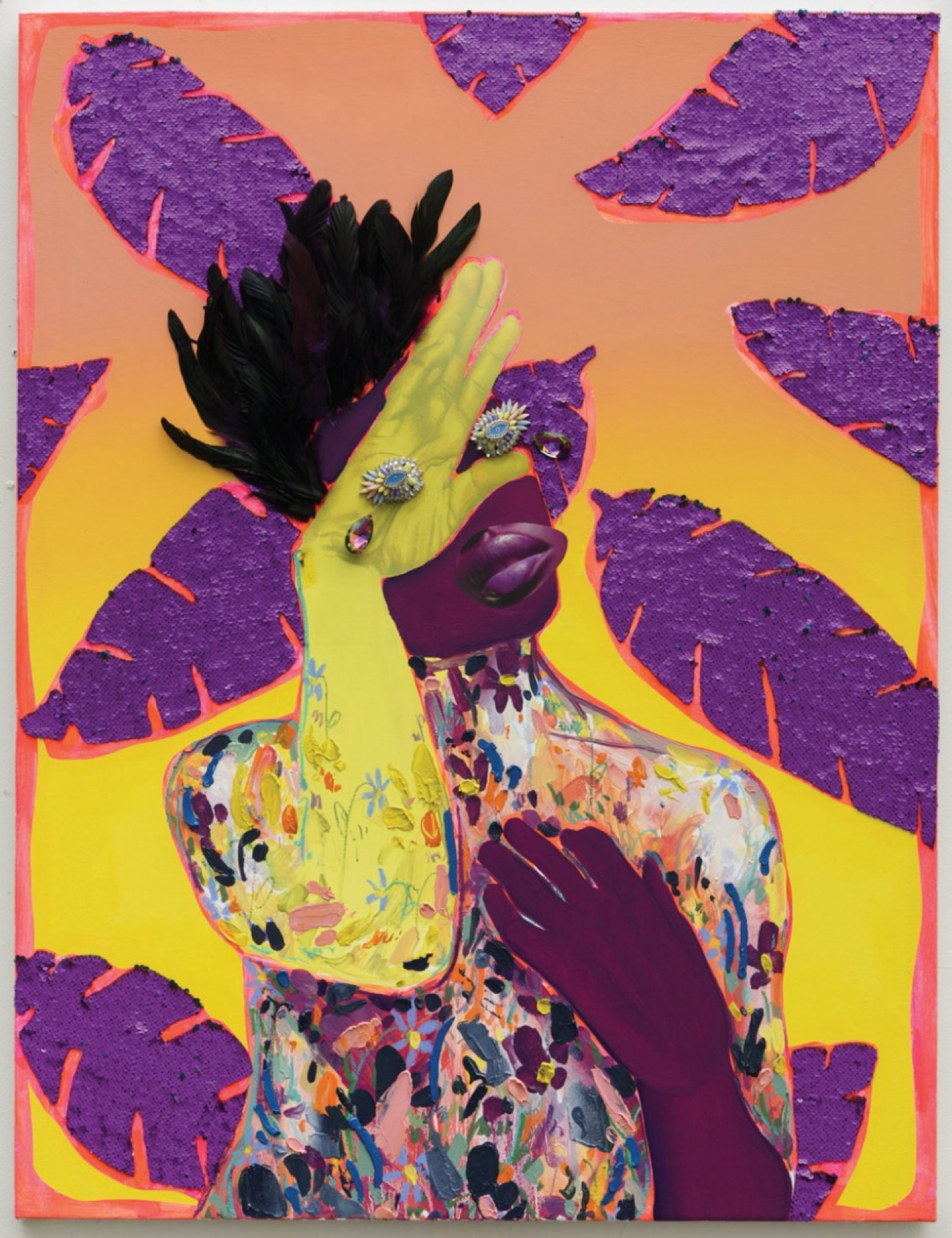

“Crown” (2017), by Devan Shimoyama. Courtesy the artist

Nobody talks about it really. I couldn’t wipe the blood up fast enough; some of it still stained the seats of the car. I felt it dry and gel brown in my hands. I tried to help Reggie the best I could and keep his head upright, so he wouldn’t choke to death.

He was gurgling in the street while I pulled his slumped body into the passenger seat. I was afraid to move too fast. I was afraid the car would come back. I didn’t know yet that Reggie couldn’t see. At the hospital, it took a while for anyone to tend to him. They packed the gash on his skull (the one on his forehead too) to stop the bleeding while he screamed on the gurney, floating in and out.

We thought it was the hysterics, him saying over and over again that he couldn’t see, he couldn’t see. Momma was there and rocked over him and prayed the best she could, even though she knew why Reggie was going down to Savannah in the first place. To do those sweet things. I know that Momma would never say it, but she felt like it happened because of his sin.

“We are the company we keep,” she said to us all the time, giving us a penny if we could recite the scripture right. “He who walks with the wise grows wise, but a companion of fools suffers harm. What happens to you is a result of what you’ve done before, who you really are, who you know. What you do when no one’s watching.”

She’d say this in some version, for every which way we went, in the pews before service, in the kitchen with sweat beads on her forehead, biting her nails to the quick as we walked through the aisles at the Piggly Wiggly.

Who are you? said Momma in my head, and Who am I? I wondered. When we were little, Momma worked a lot and couldn’t always watch us, but somehow she always felt present, and so did God, both watching us deeply and knowing who we really were in the heart.

It wasn’t too hard keeping Reggie’s secret, mostly because there wasn’t one to keep. Reggie switched too much and smacked his gum too loud and looked in the mirror too long. People knew before he did. One time I found him in Momma’s bathroom shirtless and rubbing red lipstick on his full mouth. Chet Baker was on the radio and the room smelled like cigarettes, and I watched him from the door frame because he was beautiful and his lips were full enough to carry the color well. I loved the way that Reggie looked at himself and caught his body moving, the slick, taut lines of his chest and shoulders, the grace of him, the full moon of his face.

Reggie and I would lay on the floor of my bedroom while we flipped through copies of Southern Woman and Vogue we stole from the white lady Claudine’s house.

“Celine, just so you know, when I move over there I’m gonna marry the doctor and my house will look just like this,” Reggie said while he flipped through the glossy pictures of cottages.

I wanted to ask him if he would have a room for me, but mostly I just listened to him and wondered if he would make it out there apart from me in the big world. Would he love it or end up like all the others, stripped naked, black and blue, and hung from a tree?

When we cleaned at Claudine’s, sometimes she didn’t really hate us as much. Her dementia made her less like a slave master. More sweet. Sometimes there would be snacks out for us in the kitchen with a Bible note. A slice or two of chocolate chess pie on a napkin atop paper plates, never the good china. Oil leaking off on the paper towel, pooling around the edges. If we wanted water, we would have to grab some from the spigot out back, but Claudine was sure to put the glasses out for us.

When Claudine was out at her bridge appointments, me and Reggie would play in her things. Smothering ourselves in her bath oils, sprays of Chanel No. 5, and long strings of her Oriental pearls. We would prance around the foyer and watch ourselves in the windows, taking turns coming down the staircase.

Claudine’s daughter Mabel was nothing but hateful. She was short and thin like a bird except for a little sliver of fat that stayed around her midsection. Mabel thought it was better for us to be separate from the people we served. She was always pulling her mother to the side, reminding her to let us use the outdoor bathroom and only let us drink water at the house if we brought our own cups.

Mabel was convinced that we would steal things someday, so she set us up often. Something was always a tick off; the silver double polished and close to the door, an emerald ring left on the sink, one hundred dollars casually splayed out across the bedspread, the same pearls we played in dangling off the bed post. But we never took the bait. We just wanted the magazines. We just wanted to make pretend.

One night that summer, we slept over at Claudine’s house to watch it and her grandbabies, Mabel’s daughters, who were twins. Harriet and her sister, Debbie, were loose things, both with grown-women breasts at sixteen and green, sad eyes—just enough woman to get them in trouble. When Claudine would leave for the Tennessee mountains in the summer, her granddaughters would go wild. Older boys would come pick them up after me and Reggie did their makeup and played with their hair. Each strand smelled like shampoo two times over. When we were finished dolling them up, we would walk the girls out to the Continental that was waiting for them. Harriet and Debbie would pull out bottles of Schnapps as they left the driveway, and we would watch them wave goodbye until they were a blip in our sight.

When they made it home, which they always did, we would mend them up. Combing back their dampened hair and walking them to the bathroom, fanning their pink faces as they threw up in between sobs. Vomit spewed out of them, smelling like soured peaches. But what else was there to do? There was no sense in warning them. White women will do anything when they wanna be in love.

Sometimes when the girls were passed out drunk, back at the house we would help lay them in their beds, then take the money out of their pocketbooks, and save it for our big trips down to Savannah.

“We are just charging our babysitting fee!” Reggie would say while he smiled, flashing his teeth.

The tips of the enamel were still little from the first years of his life. His front baby teeth never fell out. When the week came back around and Claudine drove back up to the house, the sisters would be all smiles and back in their goodness. They would have us clean their plates, can you put these in the sink? and when we took them up, they wouldn’t look us in the eye.

But the housecleaning money was good and the time together was better, and Reggie needed the job to keep up. He was in love with Doctor Johnson in town, who was married. Doctor Johnson liked that Reggie would dress up in women’s clothes, padded bra and everything, and meet him at Pinkie’s downtown. It’s not that he wanted to be a woman, he would tell me, but he just liked looking like one sometimes. And Reggie liked to spend the housecleaning money on big tubes of Chanel lipstick. He liked the feeling of velvet all over his lips and how the doctor seemed to really need him. As if he was really something special. As if he was worth looking at.

We had big plans that night. While we cleaned the floorboards with old rags and lye, we kept watching the clock in the living room for eight p.m. It was hot and sticky, late July, when we left Claudine’s. I told Reggie to drop me off so I could get ready and get the reefer I kept under my bed. I usually met up with Victor when we went to Savannah. He was a nice enough guy who was in the service and always offered to buy me drinks. We liked to smoke in his car and dance, while Reggie went off with the doctor at the hotel for the evening. I rushed into the house to get my things, hoping to slip past Momma, who I knew was up. Her room was at the very back of the hallway. She was a night person, perpetually restless, walking back and forth, pacing around her twin-sized bed over nothing and everything all the time.

I lingered in the hallway for a moment to see if she would say anything, I thought I heard her speak up, but she didn’t. I went into my room and pulled on my nice black dress and reached under my bed in the little box where I kept all the things I shouldn’t have. I put my hair up high on my head and sprayed on a little bit of Shalimar perfume and rushed out the door. I tried to slip out and say nothing until I heard her clear her throat. I stopped.

“I’ll be back later, Momma. I left something at Claudine’s.”

She waited awhile until she said, “Okay, love,” with a drop of sadness in her voice.

I paused again. “I’ll make sure Reggie gets home fine, okay?”

She let out a sigh. “Thank you, Celine, I am so glad he has you looking after him.”

Earlier at Claudine’s, Reggie pulled me aside and showed me a new dress he had stuffed down in his cleaning bag. He got the dress from the consignment store. It was silver and beaded, and shimmered at the bottom. He smiled as he laid it across his torso and bounced around. I hadn’t seen him like this in a while. It was nice to see him giddy. He told me he would pick me up at the street light around nine that evening, and then we would be off to Pinkie’s.

Reggie and the doctor were going places. The doctor pumped his head full of European dreams. He told Reggie about France and how people like them could live freely. Reggie swore one day they’d move. The doctor would leave his wife and baby, and Reggie would leave me, and they would start over together.

That night, when Reggie came to get me, he was feeling bold. Under his jacket he was already wearing that dress, it glittered all over him. His hair was fresh with a perm and slicked over to the side, and he was grinning, the tips of his baby teeth showing. Reggie put the windows down and I hopped in and started rolling. I lit the papers and made the car glow red. I passed him the blunt.

It was going fine until we swerved a little. The cop had started following us some time back, and it made Reggie nervous. He drove slowly, deliberately.

“Fucking pigs,” he sighed.

Reggie chewed on his knuckle and tapped his foot. He reached to turn the dial on the radio, and the car dipped to the left. Then the lights came on.

It all happened so quickly. The stop. The pull. The baton. The crack. The blood. The gurgle. My brother’s body laid on the road, gashes all over, and I watched the cop stomp the crown of his scalp, then the back of his head. Reggie screamed and screamed, then stopped altogether. I ran to Reggie. I howled, holding him and rocking him. The officer spit in front of me.

“Leave it and drive on,” he said. “Unless you want a turn, too.”

I tried to pat Reggie’s face to get him to wake up, but I couldn’t make him stay conscious. The blood was running all down his face and in his mouth. He started throwing up blood and bile and teeth.

He muttered over and over again, “I can’t see, Ceiley. Why can’t I see?”

When the cop car was far enough away, I pulled him into the passenger side of our sedan and wiped the blood from around his mouth and eyes. I screamed. His eyes were going in every direction. I drove to the hospital with blood on my good clothes. When they got him on the gurney and he passed out, I found a nurse and asked her for a phone to call who we needed most. Momma rushed there. When she saw him unconscious and bloodied, shining in his silver dress, she didn’t cry. She just reached out to hold his hand and shook her head.

A few weeks after the “accident” Reggie turned twenty-three and Miss Claudine and Mabel came to visit at the hospital. They brought Reggie chicken salad and flowers, a balloon, and a few magazines. After some time, he was finally able to sit upright and eat and talk. Most of his front teeth were missing, and the doctors gave him special tinted glasses to keep over his eyes. When Claudine and Mabel walked in the room, they took pity on my brother. Mabel set the gifts in front of him and patted his hand with her gloved one.

“Reggie, I am just so sorry to hear about your accident,” Claudine cooed, while Mabel grimaced, nodding.

“How are you feeling, dear?” Claudine continued.

“You wanna see what they did to me?” Reggie asked.

Before they could answer, he took his glasses off and his eyes splayed to the side, his pupils turned lazy and went opposite one another. The room fell silent while we all stared at Reggie. Eventually I asked everyone to leave and said my brother needed to rest.

When Reggie was on his pain medicine he kept asking if the doctor was coming to get him, so I started saying soon. Reggie would ask me every morning, Is he coming today? and I would always answer, Soon, Reggie, I promise, soon.

One day before he was discharged, he called me over to his bed and gripped my arm harder than he ever had. He took his glasses off and turned his face to me, his eyes floating all around.

“I need you to tell me, Celine. Am I still beautiful? Do I look like I can see?”

I held his face and he gave a soft grin. I could see the pink of his mouth in between his broken teeth. All the little ones were gone now. I brushed some sleep off his face. I looked at Reggie as hard as I could and tried to imagine my brother before it all got beaten out of him. My words got caught in my mouth, but I pushed them through anyway. He searched my face, waiting for the answer.

“Reggie, you are still the most gorgeous thing.”

His eyes looped around his sockets. He smiled at me.

“And if I hadn’t been there, I wouldn’t even know from looking at you that anything was wrong.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.