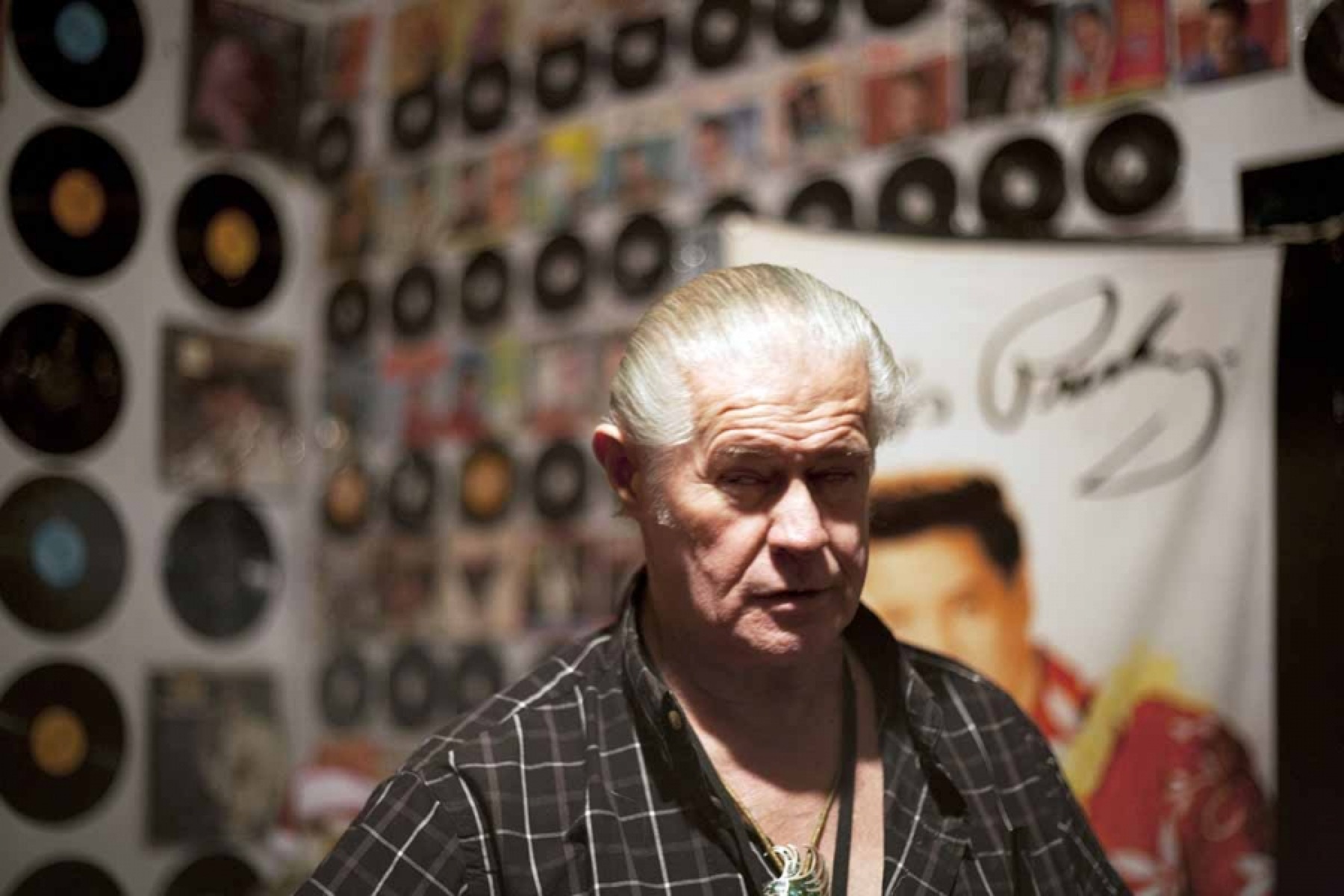

Photo of Paul McLeod by Annie Wentzell, anniewentzell.com

Like a One-Eyed Cat

By M. Randal O’Wain

The year before Paul MacLeod, the owner of Graceland Too, died of natural causes on his porch just two days after he shot and killed a local house painter, I drove my partner, Mesha, down South so that she could experience Paul’s museum firsthand.

A light drizzle fanned down Gholson Avenue that night as Mesha and I pulled up in front of the repurposed antebellum mansion in Holly Springs, Mississippi. We studied the house, engine idling, while my car stereo blared “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” One of the song’s lyrics had been puzzling me for days: “like a one-eyed cat peeping in a seafood store.” Elvis repeats it twice, before finishing the verse. The image in the lyric is cartoonish—a mangy cat sitting atop a trashcan, drooling over salmon fillets that are clearly visible, but inaccessible to him through storefront glass.

I hit rewind to listen again just as someone tapped on Mesha’s window: Paul MacLeod. He stood in the rain, wearing a money-colored dress shirt unbuttoned down to his stomach, and waved for us to get out of the car.

There was no way Paul could have known we were coming—he had no working phone number or current email address—but it seemed like he was expecting us all the same. We stepped out of the car and I shook Paul’s hand while Mesha snapped photos of two stone lions that stood guard on either side of the porch, each one wrapped in barbed wire. The lions, Paul told Mesha, once belonged to Vernon Presley, Elvis’s father. I asked him about the barbed wire, and he told me how souvenir hunters had been stealing from his yard and his mailbox. He’d started collecting his mail through a slot in the nine-foot fence that runs down the side of his house.

“If you make a video you got to pay,” Paul said, pointing to Mesha’s camera. “I already got contracts.” Paul talked fast, and his thick Southern drawl was made nearly unintelligible by a set of loose dentures that moved up and down with his lips as he spoke.

“Film producers from Sweden, Paris, Germany, ABC, NBC. MTV’s on their way now. Gonna be Graceland Too: The Movie,” he said. “Oxford, Mississippi, is doing two documentaries on me right now.”

I didn’t mention it, but I was already a member of Graceland Too, an honor acquired after I completed three full tours of Paul’s museum fifteen years before, during my teens. Back in those days I’d roll up at 2 a.m. any night of the week to show off Graceland Too to touring bands or groups of scrawny travelers who’d never been to the South before. In the early years of Graceland Too Paul’s son, Elvis Aaron Presley MacLeod, who had an impeccable photographic memory, helped run the museum. Between Elvis MacLeod’s ability to recite the exact date and time of your last visit and Paul’s crooning of “Love Me Tender” through a hot pink microphone, the tours always felt theatrical. Sometimes I’d have to wait for more than an hour as the groups ahead of me finished moving through the collection.

But that night, Paul’s memorial to the King was eerily quiet, and instead of the Pepto-Bismol-colored house I remembered, all but the white porch had been painted deep midnight blue, every windowpane blacked out. The once-fenceless yard was closed off with chain link and barbed wire. A generic OPEN sign hung on the front door.

The day before, Mesha and I toured the original Graceland and went to a Labor Day party with old friends of mine who, unlike me, have stayed in Memphis and entered parenthood and their thirties together. I’d moved to the West Coast over a decade before, and for reasons I can’t articulate my hometown no longer felt accessible to me. The back-alley charms I remember from my old neighborhood have since been traded in for pedigree dogs and yoga pants, hipster bars and upscale restaurants, and as much as the gentrification had to do with these feelings, so too did my own unfair desire for everything to stay exactly the same. Of course the city had changed, as had my friends. But I’d done my growing up away from home and so my relationship to the city was based on pure nostalgia for the past. And perhaps because of this, because I’d been feeling so distant from my younger self—the punk kid who hated Elvis Presley but loved Graceland Too—or perhaps because Paul’s son, the only person who might have recognized me, was no longer around, I lied when Paul asked if I’d been on the tour before. “No,” I said, “first time.”

I wanted to change the subject, but I also wondered what happened to Elvis MacLeod after he’d stopped giving tours back in the late Nineties.

“I heard you have a son,” I said.

“He’s with MTV,” Paul said, as he guided us into the foyer. “On his way here tonight.” He nodded assertively, but as he told us about his son’s talent for total recall he slipped oddly into the past tense. “He could remember your name, birthday, hair, eye, skin color, who you was with, where you was from, what car you drove.”

Inside the cramped entrance hall, I noticed the second-floor staircase was caged off with chicken wire. A life-size cut out of Elvis in an incredibly uncool red sweater—arms outstretched, looking like he just got the shit scared out of him—was visible through the fencing. Tacked to the wall, floor to ceiling, were newspaper clippings and press shots of Elvis. Last time I visited, the second floor was open to the public. It held thirteen TVs prepared to record as many stations in case Elvis was mentioned in any context, as well as a glass gun cabinet that exhibited a baby-blue jumpsuit Paul planned to get buried in.

“Remodeling everything.” Paul lifted his shoulders, and sucked his teeth back into place. “Unpacking eight thousand trunks with five thousand Elvis toys.” The disarray around us seemed to have more to do with stowing away memorabilia than expanding a collection.

Leaning against one of the walls was a large sandwich board that read: THE UNIVERSES, GALAXYS, PLANETS, WORLDS, ULTIMATE #1 ELVIS FAN. It was a line from Paul’s old spiel. He’d tell you he wanted the quote etched on his tombstone. In an opposite move from Keats’s iconic epitaph, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water,” Paul’s inscription demanded permanence.

We moved deeper into the poorly lit house. Paul cleared his throat, raspy from years of overuse, and slipped into his rehearsed script: “Attended a hundred-twenty Elvis concerts,” Paul said. “Was locked in a mausoleum with Elvis’s body for four and a half hours. Got the last footage of Elvis Presley alive cause I was at his house with my son when Elvis died.”

“You were at Elvis’s house when he died?” I asked.

“With his guards,” Paul said. “Going on the rounds. Every night for a month we was up at his house. Elvis fell off his toilet reading about the Shroud of Turin, burial cloth of Jesus Christ.”

On the grounds of the real Graceland, the first exhibit showcases Elvis Presley’s early 45s, and TVs along the wall track his career through television appearances, including Elvis’s 1957 performance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Sullivan told the nation that night that Elvis was “a real decent, fine boy,” and that they’d “never had a pleasanter experience with a big name.” This after CBS had refused to film young Presley from the waist down—so great was the outcry over his waggling hips.

But in Paul’s Record Room, above the fireplace, there hung one lonely LP on blue vinyl with a blank centerpiece. “There’s the last album Elvis ever done in front of my face,” Paul said. “Moody Blue.”

Back when I was young, Paul claimed this LP was an interview with Presley. I asked Paul if we could listen to it, but he didn’t say yes or no. Rather, he told me he actually had more music than Graceland proper: seventy-five thousand records and twenty-five thousand CDs. None were in sight. Plastic-wrapped 45s did line the walls, but were mostly hidden behind photos of Paul. In one picture, a young Paul poses in front of the Graceland Too fireplace, dressed in a gold lame suit, with thick, greased hair. His sideburns struck wide across his face. In another photo, he sits at a slot machine, biting down on a cigar with a woman perched alongside him—WAITING FOR THE KING, the caption reads.

“That’s my wife,” Paul said, looking at the photo. “She told me to make up my mind—either her or the King and so I handed her a hundred million in cash and said bye.”

I’d been noticing a trend with high numbers, both money and collectibles. I could be led to believe Paul’s got a million dollars’ worth of memorabilia, but a million in cash seems doubtful. Besides, the story used to go, “She told me to make up my mind,” and Paul would pause, scanning the walls and shelves that were covered with Elvis memorabilia and say, “Notice she ain’t around.”

Paul tried to get Mesha’s attention, but she was distracted snapping photos of the blue LP that may or may not have been Moody Blue. He got annoyed. “Come here,” he yelled. She walked over, and he tapped her arm three times before he pointed out a photo of his son, Elvis, black hair sticking straight up. “Remind you of the King or what?”

In the next room, much of Paul’s Elvis memorabilia was hidden beneath stacks of waist-high poster boards that leaned against every sturdy surface, each with seemingly random magazine cutouts and photos pasted to them. Paul grabbed Mesha’s arm, and pointed out a nude woman lying in ocean surf. “Playboy magazine sold sixteen million copies of me. Ten pages with nothing dirty.” Above the naked woman was a picture of Queen Elizabeth. “She might be the Queen of England,” Paul said. “But Elvis is the King of Rock & Roll.”

He flipped through a stack of boards until he found photos of himself, young in gold lame, holding two assault rifles.

“Here you go,” he said, and slapped his chest hard with the flat of his hand. “You’re safer here than you are in Fort Knox, Kentucky, ‘cause we got enough guns to stop Iraq.”

Then the tour ramped up a notch. Like an auctioneer calling bids, his anecdotes jumbled together with no connective tissue: a story about a stranger offering Paul nearly two hundred thousand dollars in cash for a stolen pair of Elvis’s underwear morphed quickly into a story about Muhammad Ali and Charles Bronson building Paul a table that rotated and lit up. A claim that Oxford, Mississippi, gave him a hundred thousand dollars in guns that he kept stored beneath the house bled into—”On the Internet right now, right now this second. Every magazine in the world,” he said. “All on me.”

As for the stolen underwear, Paul said he acquired it while the King was having sex with Barbra Streisand at the International Hotel in Vegas. How he came into possession of Elvis’s underwear wasn’t specified, and so I was forced to imagine a young Paul, plump in gold lame crawling stealthily along the floor of Elvis Presley’s hotel suite.

Paul finally led us into an archival area I didn’t remember from before. A light-up baby Jesus that had KING OF KINGS #1 written in marker across the chest sat atop a row of footlockers that lined the walls. Paul told us the chests held thirty-two thousand binders.

He picked up a five-inch-thick binder from a cluttered table and handed it to Mesha. “Close your eyes,” he said. “Pick a page at random.”

She opened the binder to the middle and read aloud:

“Elvis Presley, TV. Program:

Crook and Chase, April 10, 1992. 7:00 pm. Times on Elvis, 7:48, 7:54. Channel 30. Network TNN.”

“When did you start tracking these?” I asked.

“Been collecting fifty-nine years.”

He grabbed another binder from a bookshelf, equally as thick as the one that held the TV listings. He didn’t open it right away, but held the book out as if he were taunting us. Then he threw open the binder. Elvis Presley’s name was pasted over and over again on each page in different typefaces and type sizes. The Es and Ps ran across the pages until there were only lines that rose and fell. He said he had thirty-one more books just like that.

“Any mention of Elvis’s name you cut out?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said, drawling it out as if I were slow-witted for not getting it the first time. “It’s Elvis’s name.”

Almost as an afterthought, he pointed out a collection of red-and-green carpet squares preserved behind gilded picture frames hanging on the wall: “From the Jungle Room,” he said. “Selling in Las Vegas right now for one thousand dollars an inch.”

“These are from Graceland?” I asked. The carpet I’ve seen at Graceland is a sort of pea green instead of marble.

“I’m addicted to Coke-Cola,” Paul suddenly proclaimed, his eyes a little extra blue and wild. He turned to us. “You know about that? I got to have it. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, three hundred and sixty-five days a year—ice cold.”

“Paul,” I said. “When do you sleep?”

He ignored the question, and stepped into the Hall of Fame, a hallway lined with pictures of each Graceland Too member wearing the signature leather jacket. The room was impressive, claustrophobic. The repetition of people in the same leather jacket in front of the same fireplace was dizzying. Paul said he had logged half a million visitors. Most of the pictures had fallen off the wall—it seemed he couldn’t keep up with his memberships.

I assumed the photos—like the cutouts of Elvis Presley’s name, like how Paul tapped Mesha’s arm three times, or how he insisted that membership be given after three visits to Graceland Too—comes from a need to control the ever changing world by creating order. Collecting Elvis, for Paul, revolved around this repetition, this ability to return again and again to the moments that define not only Elvis and himself, but also those who frequented his collection.

“I remember you had one of Elvis’s jumpsuits. You still have that?” I asked Paul. I quietly panicked for outing myself. I waited for him to notice, to ask how I’d known about the jumpsuit when I’d never been to the museum. He didn’t flinch.

“My mother made that one. I’m gonna get buried in it,” he said. “And on Halloween night I’ll come back and haunt the hell out of my ex-wife.”

Back out on the front porch, a cop drove slowly by Paul’s house. The police are all members, he told us. Sometimes they brought him food—pizza, shrimp, Chinese.

“What happens to all this when you die?” I asked.

“Smithsonian,” Paul said simply, sitting down in a lawn chair. “White House, Las Vegas, Library of Congress, Graceland, Tupelo, Beale Street. They all want my collection.” Paul wiped sweat from below his eyes. “I’ll do all right by my son.”

A long silence followed. A security light flicked on, and then off again, briefly lighting the barbed wire wrapped around Vernon Presley’s lions. I tried to recall what I felt here when I was younger and Elvis was just a commodity, Paul a curiosity. Back then there was something about the overzealousness of the Elvis fan base and the ubiquity of his image all around town that caused me to dismiss the king of rock & roll and to embrace the strangeness of Graceland Too.

As we left Paul’s house, my mind kept running through those lyrics, “Like a one-eyed cat peeping in a seafood store—” The cat, even half-blind, is intent on the fish. Yet no matter how hungry he is, there will always be that pane of glass between him and the thing he wants. Elvis repeats the lyric twice before he sings, “Well I can look at you and tell you ain’t no child no more.” I’d been so caught up with the one-eyed cat line that I hadn’t paid attention to the lyric that followed. The speaker’s tone is accusatory. There’s an intimation of jealousy. Even with one eye he can see through “the child” and understand that a change has taken place, an irrevocable transformation. His suspicion in the first lines has everything to do with the one that follows, “I believe you’re doing me wrong and now I know,” and it hit me that the one-eyed cat—the man—was not starved, but made desperate by doubt, incapable of looking beyond his obsession. I thought of Paul’s collection, his steadfast dedication to preserving Elvis’s fame, and wondered if such scrutiny of one person, one thing, could ever lead to truth. After a while, I turned off the music and let silence fill the space left by the King.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.