Maternal Health in Arkansas: Introduction to a Crisis

A data-focused overview

By Caroline McCoy

Public Domain, US Center for Disease Control and Prevention

This is the first installment of a new series, "Maternal Health Crisis in Arkansas," a deep-dive into the state of maternal care from the perspectives of women, providers, and advocates working to make Arkansas a safer place for pregnancy and childbirth.

Conversations about maternal health often begin with data. Parsing the numbers—which are collected at various intervals and by an array of federal and state agencies, committees, and organizations—is crucial to understanding pregnancy and birth outcomes, the basic facts of mortality and morbidity.

In Arkansas—a state that consistently ranks among the worst places to be pregnant—the preterm birth rate was 12.1% in 2023, according to the March of Dimes’ most recent state report card. The rate for Black women was one and a half times higher. (For context, the overall preterm birth rate in the United States was 10.4%.) In 2022, the most recent year measured by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, 272 babies died before their first birthday, making Arkansas the third worst state for infant mortality, with a rate of 7.67 per 1,000 live births. Among Black babies, the rate was 12.8. Between 2018 and 2021, 141 women died while pregnant or within a year of giving birth, which equates to a ratio of 97.6 deaths per 100,000 live births. The Arkansas Maternal Mortality Review Committee, which analyzed these deaths in a December 2024 legislative report, concluded that Black women were nearly twice as likely to die pregnancy-associated deaths as white women. Racial disparities were also found among Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders, a group with significant representation in Northwest Arkansas’s Marshallese population. While these women represented 3.5% of births in the state, they accounted for 7.1% of pregnancy-associated deaths.

Acknowledging that the years evaluated in the state’s most recent legislative report span the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, which impacted maternal-care outcomes nationwide, we can look at the committee’s data set another way: Of the 141 deaths in Arkansas, fifty-nine were found to be pregnancy-related—a category that is distinct from “pregnancy-associated” in that it establishes a causal relationship between pregnancy and death. (Pregnancy-associated deaths, on the other hand, represent mortality during pregnancy and within a year of giving birth regardless of cause.) In analyzing those pregnancy-related deaths, the committee cited infection, cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular conditions, hypertension, mental-health conditions, and hemorrhage as the primary causes. Ninety-five percent were found to have been “preventable with at least ‘some chance’ or a ‘good chance’ to alter the outcome.”

Data sets differ across the agencies and review boards tasked with evaluating maternal health outcomes. For example, Arkansas’ Maternal Mortality Review Committee considers deaths that occurred during pregnancy and within a year of giving birth. The United Health Foundation, which tracked maternal mortality nationally over roughly the same time period, 2018-2022, only considers deaths that occur during pregnancy and within forty-two days of giving birth. Such disparities in method can cause subtle shifts in state rankings. But by all metrics, across all reputable reporting bodies, Arkansas ranks among the worst for maternal mortality, sharing space at the bottom with Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Louisiana.

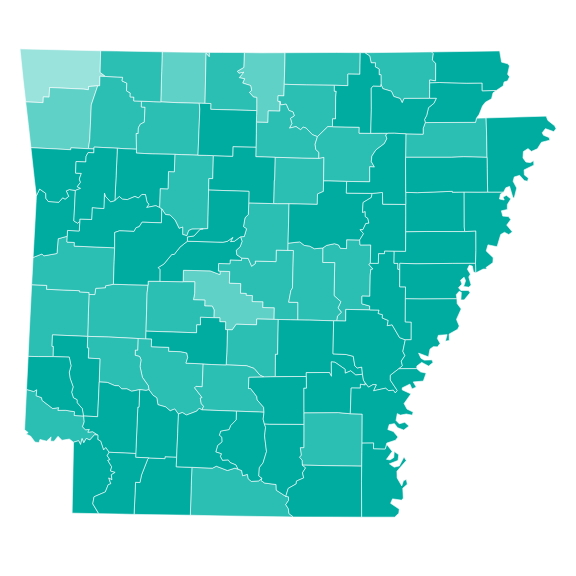

Courtesy of March of Dimes. This map depicts the Maternal Vulnerability Index for Arkansas in 2024, with "Very High" vulnerability represented by the darkest areas.

Data is essential to understanding the statistical outcomes pregnant and postpartum Arkansans face, but the data captures only a fragment of Arkansas’ maternal-health landscape.

It cannot describe what it is like to be a new mother experiencing a birthing-related health event in the only state in the nation that does not provide Medicaid to women beyond sixty days postpartum. It fails to link poor outcomes among Marshallese women with a decades-long legislative oversight that prevented all Marshallese people from accessing basic healthcare through Medicaid. It can’t yet measure the impact—on both pregnant people and their healthcare providers—of the 2022 Dobbs decision or Arkansas’ resulting trigger ban on abortion at all stages of pregnancy. It doesn't describe the transportation-related burdens of seeking pre- and post-natal care in a state where 45.3% of counties are considered maternity-care deserts by the March of Dimes. Years will pass before data can fully quantify the potential benefits of a state-wide push to train 200 doulas, an initiative guided by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, the Ujima Maternity Network, and Birthing Beyond.

These stories are at the core of Arkansas’ complex maternal-health crisis, and they must be told by the people who live them. The data will be here for reference and as support to the voices that it addresses.