Iguanas! Divisive Conquerors of Key West

The non-native species has invaded South Florida and its culture

By Zack Ford

Photo by Ingrid Siegert

“Yuck,” said the park ranger after I’d said, “Iguanas.” Then she offered, “There was a man down here in one of the parks who used to deep freeze them.” She gesticulated the big box of a top-lidded industrial freezer. “That’s the humane way to kill them. Then he’d use them as chum. But, you can’t kill them, they just . . .”

“Keep coming back,” agreed a man wearing a shirt patterned with jaguars—the kind of shirt Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams would have tittered about over rum cocos. My mother, who painted an acrylic iguana nestled in a sea grape bush on the kitchen wall of my parents’ retirement home, once waited their table at a now-shuttered Italian restaurant on Truman Avenue.

Here in Key West, and up the archipelago into mainland Florida, iguanas are a numinous nuisance: they are hated, but they are also beloved. Odi et amo—the Roman poet Catullus once wrote about a lover—he both hated and loved her. Is there a word for that paradox? Perhaps “obsession” fits. Iguanas are inspirational: Williams wrote the Broadway hit The Night of the Iguana; Shel Silverstein, also a resident of Key West, once poeticized about an iguana in a sauna; and Jimmy Buffett, perhaps the most famous Key Wester of all, once signed a band called The Iguanas to his Margaritaville Records label.

But there’s also a forever-war being waged against these lizards. Sit at Café Marquesa sipping an Orange Sherbert Mimosa, and you might see a man with a bandana over his face popping off rifle pellets like a guerilla rebel. Such soldiers are protecting the fulgent orchids lashed to trees with twine and moss. In addition to devouring carefully cultivated flowers, iguanas also shit in pools, exposing swimmers to salmonella, E. coli, and even hookworm; they also shit on, well, everything. But despite this forever-war, these lizards have also become a localized mascot. On Southard Street, across from the storied Green Parrot Bar, there’s a wheatpasted graffiti on one of the concrete telephone poles depicting an iguana with a paint-roller, comically overpainting the number for an iguana removal service. The message is clear: iguanas are an invasive species, but they’ve also wheedled their way into our hearts and minds.

They are majestic, they are grotesque. There might not be a perfect word for Catullus’ predicament, but there is one for iguanas. It’s iguanas! The salacious cadence of their very name reifies them. (As if to double-down on that point, the scientific name for the common green iguana is: Iguana iguana.) There is an obscenity to their appearance: the prehistoric green rictus may open slightly to allow a glimpse of the soft vaginal pinkness inside. There are sharp teeth in there, serrated like a handsaw. Will they attack? Yes. I confirmed this at the Urgent Care on Roosevelt Boulevard, where they’ve treated at least one iguana bite. But like many things in nature that are dangerous, their appearance is arresting. There’s a gargantuan one who lives down at the post office, with a dorsal crest so vibrantly orange it’ll stop your bike. I named him “grandfather,” gendering him based on his larger notched dewlap and prominent jowls. Am I an iguana sympathizer?

Everyone has a connection to them. At Mallory Square, a sculptor named Ryan uses pliers to bend the semblance of an iguana out of aluminum wire. “I’ve made over a hundred iguanas,” he says. At the Old Town Bakery, a barista named Brooke says, “My dog kills them!” She has a dry-erase tally board at home labeled Iguana Tracker—read, kills. The tallies total eleven. She shows me a picture of her miniature dachshund, licking its chops while standing over a dead one green as money.

They perch on branches above the maloca at Key West Yoga Sanctuary. I wonder what yogis think of them. But you can’t get a straight answer out of a yogi, it’s like they’re media trained on questions of passing judgement. They neither love nor hate iguanas. Lalita, on a scale of 1-10, hates them 0. She has a “healthy respect” for their being so “ancient looking” and feels sorry for them when they fall with thuds from branches, which iguanas do when the temperature drops below fifty degrees Fahrenheit and they go into a cold-stunned state like they’ve peeped Medusa. And like this herpetological gorgon, iguanas are also afraid of their own reflections. Bliss, on a scale of 1-10, likes them 9. Diplomatically, he says he appreciates them, as he would appreciate any animal. Finally, I stop a yogi on her banana-yellow bike on the corner of Whitehead and Eaton. In an aside, Sara admits it, she hates them. “They’re scary,” she says, and repeats it again. I say, “What if I told you iguanas have a functioning third eye? It’s called a parietal eye, and it tracks light and movement.” I think maybe that will make a yogi hate them less, since yogis are always trying to cleanse and open their own third eyes. “No,” she says with emphasis, and rides off.

Iguanas are invasive (a loaded word, I know). So, where did they come from? I search out an answer in the Monroe County Public Library on Fleming. Breana, an archivist at the Florida Keys History Center, gasps when I tell her some people hate iguanas, and she makes a heart with her hands, bristling at their bad rep. She feels bad for invasive species in general. “They didn’t ask to populate here,” she says. A 1937 article from the Charlotte Evening Post begins: “‘Monster’ Proves Harmless Iguana—The monster of Ft. Myers Beach was in the city jail today, as authorities sought to halt the sudden scares it has given residents of the vicinity.” A 1935 Atlanta Journal-Constitution article describes an Alabama couple being “paralyzed with fear” at the sight of a “dragon” in the road. Breana and I turn up bad press, but not an origin story.

Photo by Brooke Trammell

Mader says strong winds and rafts of debris have historically pushed iguanas across the water from Mexico and Cuba.

Meanwhile on Duval Street, a police officer draws his gun, and a man on a bike tumbles painfully onto the asphalt. There are people running. A helicopter whirs in a cloud of black smoke. The Conch Train, a trolly for tourists, flies through the air like a child’s toy tossed. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church is under attack—by a giant fire-breathing rooster and an iguana half the size of Godzilla. The oil painting, titled “Keyzillas: Kings Of Destruction,” hangs in the Stone Soup Gallery, where local artist Loren Ilvedson is having a show.

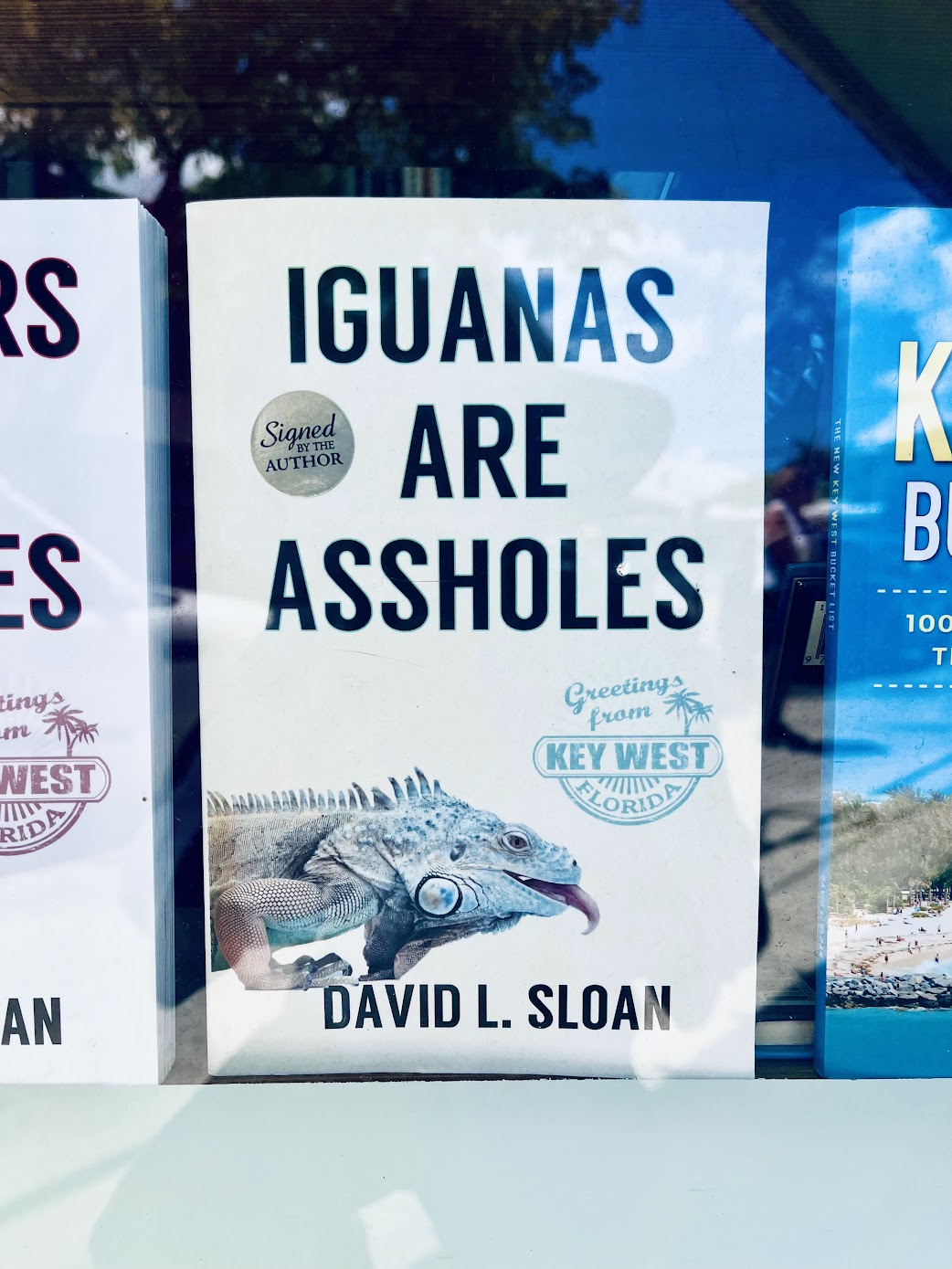

Iguanas have never razed a church tower, but they did once eat Ilvedson’s spinach plants. Almost a century after the Alabama man hit his brakes and almost threw his wife “through the windshield,” iguanas are still getting bad press. But they’ve also become muses, perhaps anti-heroes. And our feelings about anti-heroes are complicated, aren’t they? At Key West Island Books, a signed copy of Iguanas Are Assholes is propped in the front window. But despite the libelous title, if you turn to the back page, in the “About the Author” blurb, David L. Sloan admits to being a “begrudging iguana enthusiast.” Likewise, to be fair, the iguana-loving archivist did admit she doesn’t completely love them, saying, “I do hate they dig the cemetery graves out.”

The sunbaked cemetery up on Solares Hill is a hotbed of iguana mating. Spiked bodies undulate violently like snakes as they sprint around tombstones. Striped reptilian tails slip and disappear into the bunkers of broken cement sarcophagi. Cream-colored eggs the size of ping-pong balls are interred in the ribcages of human corpses. A female iguana can lay between twenty and seventy eggs in a year. In yet another turn of paradox, these extinction-defying dinosaurs explode life from a tableau of death. Horrifying, no?

They live in squalor. And at a talk at the Tennessee Williams Theater at The College of the Florida Keys, Dr. Doug Mader, author of The Vet at Noah’s Ark and the only private veterinarian permitted to treat Key Deer, I get an answer to how iguanas came to the Keys: they arrived in squalor. Hurricanes, to be exact. Some perhaps on floating coconuts. Mader explains there is scientific evidence for this, and says iguanas are naturally invasive, and not exotic invasive like the Burmese Python that was released into the Everglades by negligent owners. Iguanas are incredible swimmers (with the added ability to inflate their bodies to float), and Mader says strong winds and rafts of debris have historically pushed iguanas across the water from Mexico and Cuba. He has all the incontrovertible charts and correlating statistics, demonstrating for instance how Hurricane Wilma drove some Iguana iguanae across the Atlantic into the Dry Tortugas.

“People love iguanas all over the world, but not in the Keys,” Mader says, and a murmur of agreement ripples through the crowd of a hundred. He tells us how sometimes iguanas surpass being muses to become art themselves: breeders have taken to mating iguanas for color, turning their leathery scaled skin into a canvas. A designer canary yellow iguana with swirls of Cheeto-orange once fetched around $30,000. The newest, most unique color morphs score the highest prices.

An advertisement in the Keys Citizen announces like a pithy Terminator one-liner: IGUANAS IN KEY WEST NOW HAVE A NATURAL PREDATOR.

I wondered what the political establishment thought about iguanas. DeeDee Henriquez, mayor of Key West, answered me with slippery evasion, demonstrating that she understood full well how fraught the psyches of her constituents could be about them. “I don’t particularly like iguanas. I am not anti-iguanas,” she finally responded to my several pressing calls and emails. Smart side-step of an answer, I thought, since down here, iguanas are a polarizing, hot-button issue.

Though politicians are noncommittal about them, reverends in south Florida bless them. Daybree Thoms, minister at Unity Church of Key West, says that usually winged creatures are drawn to the vibration of her animal blessings, and though she’s blessed many dogs, cats, and horses, she doesn’t know how she feels about reptiles. But during one such come-one-come-all blessing session two years ago, while she sat on a reed mat under a tree, an iguana approached. She told me she blessed it with good health, long life, and safety, adding gravely, “Even though there are iguana hunters out there.”

And there are. An advertisement in the Keys Citizen announces like a pithy Terminator one-liner: IGUANAS IN KEY WEST NOW HAVE A NATURAL PREDATOR. The company’s voicemail says, “We’re probably out chasin’ giant lizards.” I finally reach Quentin Garcia, who goes by Q, of Invasive Species Removal of Key West, LLC. He’s more than happy to invite me along. He gives me the caveat that he usually likes to vet people a bit before he hands them the rifle, and I say that’s fine.

Q picks me up in the parking lot of the local DQ. His Jeep is the yellowish green of a fire engine. I ask him why not iguana-green, and he assures me he’s buying a green light-rack. The first place we patrol is the National Weather Service building. Iguanas dig burrows like the gophers in the movie Caddyshack, and Q shows me a satellite dish that iguanas once undermined. This knocked out the hurricane tracker for a while. Q says he’s killed at least four hundred of them here, but today we can’t spot one—proof Q is succeeding. We get back in the Jeep. Q says he considers himself an ecologist, and speaking of weather, he doesn’t completely agree with Mader’s assertation that iguanas were blown over. “There weren’t any iguanas down here when I was a kid,” Q says. He’s a fourth-generation Key Wester, and he blames the iguana invasion in large part on Hurricane Andrew smashing a serpentarium in Miami back in the ‘90s, freeing scores of them, though Q concedes perhaps a few caught the wind.

Q has two hundred iguana removal accounts. He’ll never be able to kill them all but culling them is a way to balance the ecosystem. In 2024, he claims over three thousand kills with a ninety percent recovery rate, and that he’s eighty percent effective on one-shot kills. He estimates he gives fifty to a hundred pounds of iguana meat away each week, to people who like to eat it, though he can’t sell it unless he successfully petitions the Department of Agriculture to be allowed to do so. He ate it once, but he grilled it, which apparently is the wrong way to cook it. “I’d put it in a stew next time,” he says, explaining how the meat becomes less rubbery in a boil. He adds, “I’m not going to kill an animal I’m not going to be able to eat.”

Our next stop is the cemetery. I notice a small aquamarine skull on Q’s dash as we pull through the gates. Many of the tombs are cracked and listing from the iguana warrens beneath them. Q gives me a Day-Glo vest, which I put on like a flak jacket as he whips out a Whisper Fusion Mach 2 air rifle, capable of shooting pellets at 1,420 feet-per-second. Q doesn’t like to see the animals suffer. “You want to hit them between the ear and the cheek patch,” he advises. Binoculars to his face, Q spots an iguana on the high branch of a strangler fig tree. I can’t see it, but Q shoots, and then I see a single claw fall limp over a branch with the drama of Citizen Kane dropping the snow globe. It’s still alive, curled around the branch, and Q pops off a few more pellets until the green body flops through the air, hitting every branch on the way down. Q lays the dead body on a concrete parapet, pokes it in the belly with a finger, and says, “It’s full of eggs.”

As destructive and out of place as they were, I’d developed a soft spot for these creatures.

Back in the Dairy Queen parking lot, I thank Q for taking me along, and he gifts me the safety vest, IGUANA REMOVAL emblazoned on the back. When he also gifts me a small gray epoxy skull, his trademark, which he makes, I notice the fingers on my left hand are splattered in blood, from when Q delivered the fatal headshot after the iguana had fallen from the tree.

I calm my nerves with a perspiring pint of reddish Iguana Bait beer. The beer is a purity-rule-bending Kölsch complemented with hibiscus. On their website, the Florida Keys Brewing Company explains, “We named it Iguana Bait because the local iguanas’ favorite meal is big, beautiful hibiscus flowers.” I think and drink. How do I feel about iguanas? I agree iguanas, as a transplanted species, should have their population checked to maintain a balance in the ecosystem. Q told me utility companies had even spent millions shielding transformers from iguanas lying across them and causing power outages. Though the mayor isn’t personally anti, it is legal to kill on sight. But I was also nauseated by the Christmas colors in the hot spring sun, by the red blood pouring down the green leathery face. It was hard to swallow the beer, and I had no appetite at dinnertime. As destructive and out of place as they were, I’d developed a soft spot for these creatures. I thought of what Williams, in his famous play, called “the logic of contradictions.” For him, that cold-blooded iguana scratching around under the on-stage verandah with a rope around its neck was a sanguine symbol for human salvation. Williams had his characters set it free.

Catullus claimed he was “tortured” by his paradox. But in our modern world of 5G-speed reactionary opinions, it’s sometimes a soothing deliverance to just say, “I don’t know.” Sure, I kind of hate them; my dog snarfs up their poop as I pull the leash and curse. I’ve even been shat on by them myself. But I’m also glad Q never offered the gun, and I didn’t shoot one, just as I’d promised the reverend I wouldn’t.

Odi et amo—iguanas, unchanged and unevolved since well before humans began walking in time toward our own demise. Perhaps more meaningful mysteries could save us from our stark certainties. After all, aren’t we humans also a hated-and-loved invasive species?