Waxahatchee: She Lives for the Sake of the Song

Six days on the road and through the past with Katie Crutchfield, a new giant of American songwriting

By Jenn Pelly

Photograph by Molly Matalon

Brother Bryan Park is a two-block stretch of grass and trees circling an abandoned pool on the southside of downtown Birmingham, Alabama. It’s more like a rough-edged town square or the set of a teen movie, seemingly designed for kids to skate in, to wreak secret havoc. When the songwriter Katie Crutchfield was in her early twenties, she penned a taut, suspended ballad called “Brother Bryan,” released in 2013, in memory of her close friend Tripp Norris. Beloved in Alabama punk, Tripp was a quick-witted musician and poet who fronted the hardcore band No Price Paid. He also instigated a high school tradition dubbed “Wretched Wednesdays,” where everyone drank here in this park until dawn. “He was this funny, mythological character, like the Blaze Foley of the Birmingham scene,” Katie says one weekday morning in May of 2024, comparing her late friend to the outlaw country protagonist of “Drunken Angel,” the 1998 Americana standard by her hero, Lucinda Williams. Tripp’s struggles with alcohol and drugs found him dead from a heroin overdose in 2011, at twenty-two.

“Brother Bryan” begins—

I said to you on the night that we met, “I am not well”

Our habits secrete to the sidewalk and street, our civic hell

And we covet the dark, share a cab to the park

And you let me

Speak of bearings undone, silver hair in the sun

We are only thirty percent dead

Before she zooms out—

You can’t hold up a story so heavy

We tell it so rarely

BIRMINGHAM

It’s the first hour of my first day on tour with Waxahatchee, the moniker by which Katie has released six albums since 2012 and the name of the six-piece band she now leads. The group has been on tour for a couple weeks already. I joined them here in Katie’s hometown, where she began writing songs over two decades ago, when she was fourteen, forming bands with her identical twin sister, Allison, in high school. Now thirty-six, Katie has lived many lives. From high school DIY popsmith to feminist punk hero, from indie rock idol to her current status as a giant of heartland poetics, she has ascribed onto music many myths. A punk musician from New York once described witnessing the Crutchfields’ teenage musicking in Alabama as his personal “I saw the Beatles in Hamburg!” moment. Their first acts were as Birmingham legends.

I will spend six days on the tour bus with Waxahatchee from Alabama until Texas, where Katie recorded her latest record, the Grammy-nominated Tigers Blood. For this stretch of the tour, the bus’s twelve bunks are filled with five other band members, a five-person crew, myself, and, for a few days, Katie’s boyfriend of seven years, the songwriter Kevin Morby. Katie’s got her own little room at the back of the bus. With Waxahatchee, I will glimpse an awe-inducing pink sky behind the hundred-year-old Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I will spectate the daily cattle drive outside the venue in Fort Worth, Texas. I will talk with theater managers and security guards across the South about hitchhiking and dropping acid and planetariums and Sid Vicious. I will hear Katie croon along to every word of “Pancho and Lefty” outside of a cowboy hat shop. I will listen to soundcheck covers of Townes and Lucinda and George Jones and the Dead. I will write poetry in the Houston heat on a guitarist’s extra typewriter. I will be awoken in the coffin-like claustrophobia of a bus bunk by one crew member’s horrific night terrors. With four members of Waxahatchee, I will briefly attend my first rodeo.

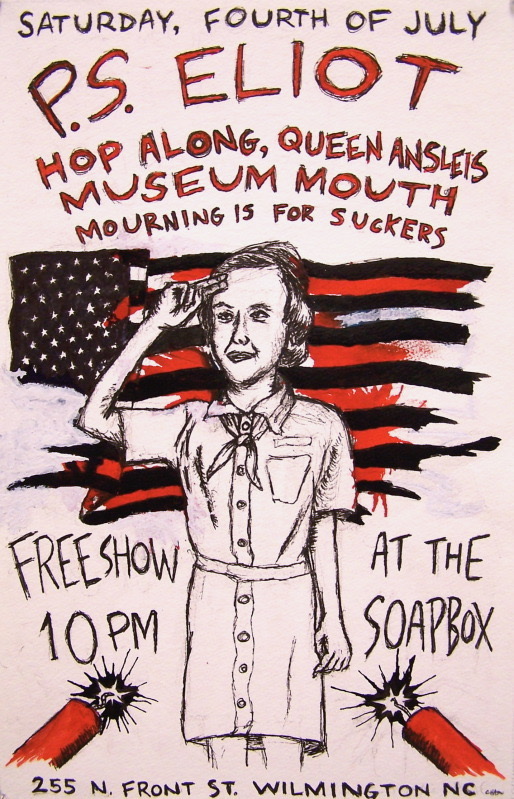

Here in Birmingham, we are, like a Waxahatchee song itself, cutting straight to the heavy stuff: We had to start at Brother Bryan. That’s true of the park as much as the song, its muse as much as its subtext. Katie learned of Tripp’s death while on tour with Bad Banana, a moxie-fueled pop-punk project she co-helmed with Allison—though back then, the Crutchfields were best known in the underground for their raw, wordy rock band P.S. Eliot, whose two whirlwind full-lengths were DIY talismans so filled with language and life that the songs seemed to burst at their tattered seams, the lyrics compressed and blurred, Katie’s sing-shout occasionally ringing clear to say “I’m feeling indestructible” or “I don’t really care about the future” or “I’ve got my whole life ahead of me!”

P.S. Eliot flyer courtesy Waxahatchee

A month and a half before her friend’s passing, during the first week of January 2011, Katie self-recorded her lo-fi debut as Waxahatchee while snowed in at her childhood home in Birmingham. With the unsparing self-examination of a punk Joni Mitchell, she was probing romantic tangles and early-twenties disarray through a haze—lyrics refer to “beer to shotgun,” “little pills,” “whiskey and Sam Cooke songs”—as if creating a lawless armor from candor, invincible. “I was really fucked up when I made that record,” Katie, now seven years sober, tells me at Brother Bryan Park. “I was like, I’m going to be stoned and drunk and make this crazy record in a week. I’m popping Adderall, I was out of my mind. I was trying to be Townes Van Zandt. I really glamorized and attempted to embody this troubled artist, this messy person.” It’s an image she now counters in seemingly every creative decision. When she released American Weekend in January 2012, however, she was self-aware. Her liner notes dedicated its cutting songs to “anyone who had woke up and realized their identity is blurry, has had to clumsily get to know themselves, has hit a bottom, has felt self-deprecating and vagrant and to anyone who has ridden out a shitstorm. . . . Lastly I would like to dedicate all these songs to the memory of my friend Ricky David Norris III.”

Katie’s sobriety coincided with her most widely acclaimed songwriting, beginning with her 2020 masterpiece Saint Cloud, the first Waxahatchee record to foreground the country sensibility that soundtracked her youth, her soulful voice pressing out ecstatic ache like a millennial Emmylou. But in 2011, Tripp’s death had changed her, and her work. The shift was immediately reflected in the depth and severity of her second album, 2013’s Cerulean Salt. “One of my best friends and people in my life who I looked up to the most died of a drug overdose,” she says, with the matter-of-fact certainty of a person who has scrutinized her life’s ruptures and turning points. “I started to look at [addiction] and write about it in a different way after that.” At that point, Tripp was not the only person close to Katie struggling with substances, and she was grappling with it all. “My sister’s eyes flow like rivers or wine in your absence,” Katie sings of her younger sister, Sydney, on “Brother Bryan.”

“Only since I got sober have I really thought about writing about addiction—in a way that other people can consume and process—as a bit of a public service,” Katie says, sitting on some brick steps that encircle the park, which is completely empty besides the landscapers working in the distance. “But when Tripp died, I didn’t understand it at all. I remember knowing he was doing heroin, but I didn’t understand how dangerous that was. I knew it was bad, but no part of me thought he was gonna die. I didn’t understand my own mortality, or his mortality. It was so intense and I didn’t know how to handle it. It was more like: This is immediately what’s in front of me, and it’s a very desperate situation. So writing about it was my way of processing it.” As she wrote through brutal reality, she was beginning to depict the entanglements of grief and love in tandem, as they play out in real life, as devastation.

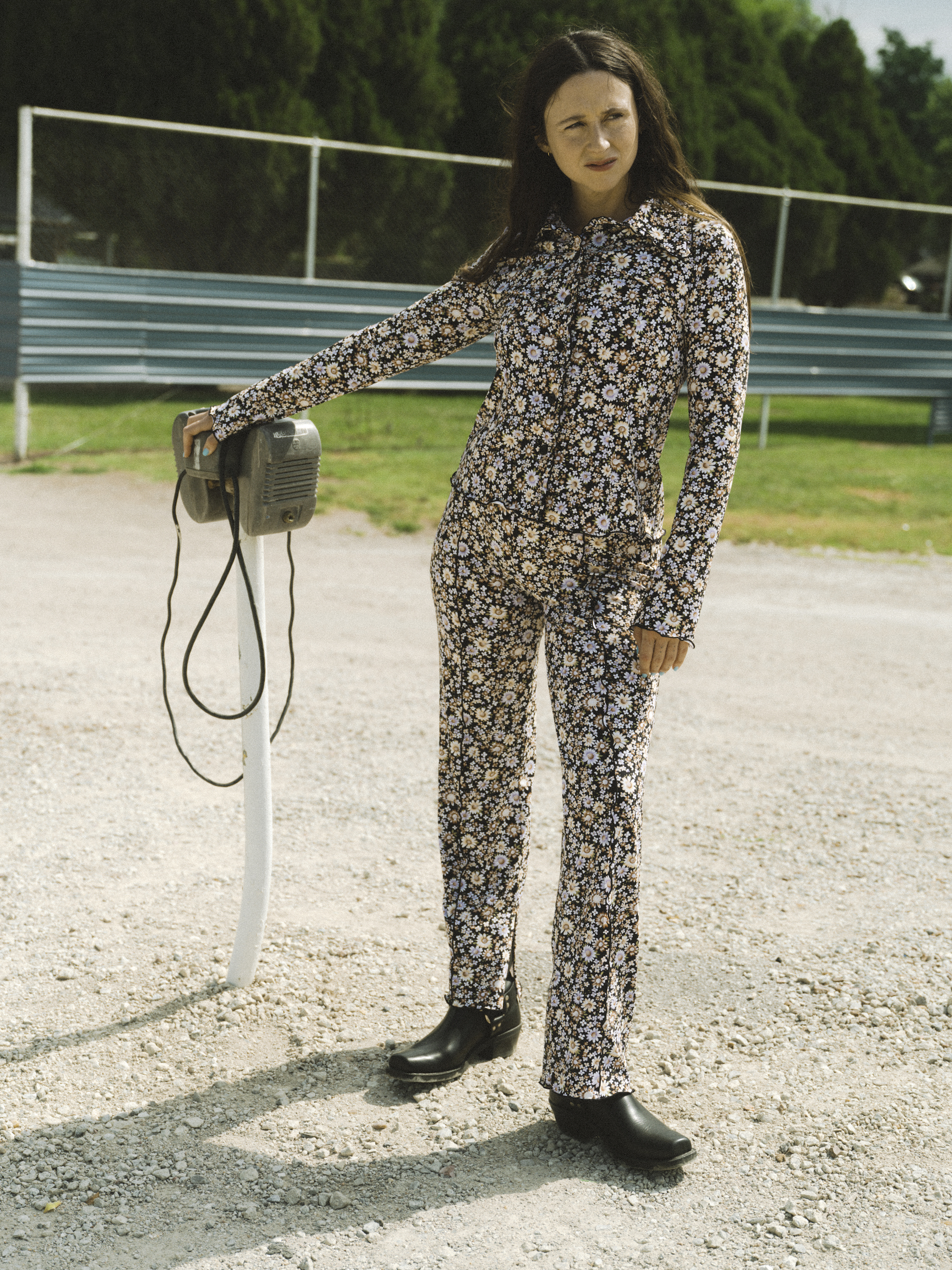

Photograph by Molly Matalon

Katie’s music helped me form a sense of self at twenty-two. I could not imagine then how true that would continue to feel at thirty-five.

Katie has wide eyes and long, mermaidy brown hair that she fastened into a loose low bun before heading out for our walk, donning her signature offstage footwear: socks and slides. This is the first time in years I’ve seen Katie out of high-styled stage mode. Today as ever, she’s a person I’m inclined to characterize as a good hang—“both a powerful and easy presence,” as her bandmate Eliana Athayde later puts it to me. Katie has become a woman of boundaried equanimity who eats barbecue and loves basketball and affirmatively says “dude” approximately six times per hour, and who still seems to live by the Beach Boys adage inked to her forearm, among her countless tattoos: i just wasn’t made for these times.

Bracing the heat with us on our downtown Birmingham walk is Katie’s dog, Ernie, a tiny and energetic Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Katie hasn’t explored these streets on foot since she was a teenager. We had headed to Brother Bryan Park from the ornate Lyric Theatre, where, tonight, she’ll play her biggest hometown show to date. We passed the gigantic, blinking marquee of the Alabama Theater, where Katie tap-danced in The Nutcracker as a kid. She points out a small bar called The Black Market, where she played an early high school gig under her original solo moniker, King Everything, a Guided by Voices reference. As we cross a footbridge into quieter south downtown, Katie points below to the train tracks where she and her friends would often post up—they called it “The Spot”—drinking and blasting indie rock (Titus Andronicus, Rilo Kiley) and punk (the Ergs!, Lemuria) from their parked van, which they’d bought off a guy in Huntsville for $900 to use on DIY tours. We walk by the former location of Cave9, the storefront all-ages venue where Katie and Allison learned about punk as high schoolers—how to book shows, make records, screen print shirts—and where their teen band The Ackleys always packed the house.

As a young musician in Alabama, Katie’s ambition was to find her people. But friends who knew her then said it was always obvious she would make her life in songs. “Even when I was fourteen and she was coming across the hallway to knock on my door and play me a song she wrote, I have always been like, ‘That’s the best song I’ve ever heard, this is just what you’re supposed to do,’” says Allison, who, after playing guitar and keys in Waxahatchee and her own band, Swearin’, for years, currently works with Katie as her A&R rep at Anti- Records. Katie left Birmingham because Allison did—first for Tuscaloosa, later Brooklyn, then Philadelphia—often looking to her twin back then for direction or affirmation, always sending Allison the songs she’d written first. “I needed her approval,” Katie says early on our walk. This is a conversation Katie and I have been having for over a decade, a need that—as an identical twin myself—I’ve related to for as long as I’ve known her.

One of the first times I can remember seeing Katie and Allison Crutchfield perform, in Brooklyn, was at a graffitied, straight-edge punk warehouse where bands set up in the kitchen and the audience watched down from a lofted perch, and where I had mostly been for hardcore shows and vegan potlucks and to occasionally crash in a bedroom a few feet away from where the band was playing. We met the following year, in December of 2012—when a scrappier iteration of Waxahatchee played its first full-band set at a metal bar in Brooklyn—but Katie and I had by then spent years in the same DIY punk-feminist subculture. I had downloaded Crutchfield MP3s from the popular punk blog icoulddietomorrow and saw them play at spartan community centers and the post-riot-grrrl Ladyfest and quasi-legal art spaces where there was no barrier between performer and audience. I had witnessed the edges of Katie’s poised howl silence the loudest rooms.

In some sense our meeting felt predestined. We’re both mirror-image twins, and our birthdays are mirrored: theirs January 4, ours July 4, 1989. Our mothers are both Aries. Our younger sisters—we are both one of three—were born in 1993. We are each the younger, shyer twin to our more outspoken sisters (Allison is two minutes older). In another doubling, twelve years ago, my twin sister Liz went on the road with Waxahatchee, beating me to the punch of writing a tour diary (annoying) when she worked for an alt-weekly and Katie was playing house shows. Through the years, we’ve all discussed how being a twin can steel you with self-belief, a built-in us-against-the-world support structure. As the elder Crutchfield twin once put it, in a zine about P.S. Eliot authored by Liz (welcome to twindom’s house of mirrors): “When Katie and I feel really inspired by something, we can build each other up in this way where we have complete courage in ourselves and complete confidence.”

Photograph of Katie by Allison Crutchfield

Photograph by Jesse Riggins

Photograph courtesy Waxahatchee

Photograph courtesy Waxahatchee

We had done our first interview in Philadelphia a week after we met, and hopping into the passenger seat of Katie’s car at 30th Street Station, she already felt larger than life to me. Inside her shared West Philly rowhouse was evidence of why: walls covered in punk flyers and relics of her already storied musical past; basement filled with gear where she and her bandmates recorded themselves. That day in 2012 we discussed her growing profile, her Southernness, the formative influences of Fiona Apple and Jenny Lewis. The Crutchfields’ existence gave me confidence as a young woman invested in music and language and feminism, longing to hold onto the integrity and discernment of a punk ethic without limiting myself. They seemed to be creating their own world—defiant, honest, literary, emotionally direct—filled with adventure and unvarnished songs narrating the feeling of first discovering how big the world is, and finding your people and your place in it. Language was always paramount: Katie still makes words into instruments, finding the multisyllabic music in “reticent” or “iconoclastic” or “scientific cryptogram” and sending it all in flight as strength. Katie’s music helped me form a sense of self at twenty-two. I could not imagine then how true that would continue to feel at thirty-five.

But this is a lot of history—and today Waxahatchee rarely makes me want to think about the past. When Katie invited me to come on tour, we’d been largely out of touch for about five years—the years she spent getting sober, relocating to the Midwest, logging off, honing her craft, changing her life. I had known a new era of her art was coming. In the fall of 2018, she told me, “I’m not going to put out a new album until I’ve written my Idler Wheel,” referring to Fiona Apple’s 2012 masterpiece. While today Katie laughs that off as “a psycho thing to say,” the comment revealed something undeniable: she was architecting a life to live for the sake of her songs.

Before the tour, I asked Katie if she’d be willing to dig a bit deeper into the stories behind those songs. She said she had already been thinking about it. She wanted to check with her family first.

Making our way back to the Lyric Theater, Katie enthusiastically recounts how it happened that, a couple nights ago at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, she was joined onstage by both Wynonna Judd and Lucinda Williams, two legends she’s befriended in recent years.

Lucinda and her husband Tom were already planning to watch the show before Jake “MJ” Lenderman—the twenty-five-year-old North Carolina indie rocker who sings and plays guitar all over Tigers Blood (and, though not a regular member of the Waxahatchee live band, came along for the Ryman show)—suggested they cover “Abandoned,” Lucinda’s damning 1988 breakup song. “Jake didn’t know anything about Lucinda coming, and I was like, ‘That’s great, you know, she’s probably gonna come, and he was like . . .”—Katie pantomimes jaw-dropping awe.

She texted Lucinda’s husband to give him a heads up about the cover, and he said she’d likely want to join. So Katie texted Lucinda, who she had never sung with before onstage, and “she asked a bunch of questions, but then was like, ‘Yes I want to’—and showed up at soundcheck and blew us all away.” Backstage, Lucinda held court, drinking red wine and sharing stories with the members of Waxahatchee and their opening act for the tour, the Australian six-piece Good Morning. “Jake was nervous—I kept trying to pull him over, ‘Come talk to her,’” Katie recalls.

When I speak with Lenderman later on, he tells me it was “probably one of the biggest moments of my life.” He says working with Katie—as on their Tigers Blood duet “Right Back to It,” a rootsy ode to the beauty and anxiety of long-term love that already feels like a modern classic—has instilled him, too, with confidence. “Her vocal pocket really blows me away . . . the rhythm to how she sings,” Lenderman says. Famously offline herself these days, Katie inspired him to quit social media, which he says “was a huge thing for me” and “cleared out a lot of noise” while writing his own acclaimed 2024 album, Manning Fireworks. “I feel more comfortable saying no to stuff,” he says of Katie’s influence. “I look at her as somebody who’s navigating our line of work in a healthy way, having boundaries and protecting the part of you that people loved in the first place, and staying true to what you want to do.”

After Katie and I conclude our psychogeographical walk through the Birmingham heat, she relaxes before the gig, while Kevin and I decide to catch a ride across town, determined to glimpse a folk art mural dubbed the “Real Alabama Music Hall of Fame”—he says I must see it. It spans a small wall inside the music venue Saturn and includes the likes of Emmylou Harris, Sun Ra, and Brittany Howard. Atop the painted compendium of local heroes, testifying to their stature here, Katie and Allison’s faces preside over the whole wall, first-row and center.

Back in the Lyric’s basement, I am hanging out on some leather couches with Waxahatchee multi-instrumentalists Cole Berggren and Colin Croom when the click-clack of an old typewriter begins to fill the cavernous space. The guys direct my eyes toward the band’s guitarist, Clay Frankel, posted up a few feet away, typing loudly. Apparently he has been toting the typewriter around since the beginning of tour, and in New York he picked up a second. (Alluding to a recent album she loves, Katie has taken to calling Clay the tour’s own “Tortured Poets Department.”) Clay and Colin, best known for their Chicago band Twin Peaks, extend Waxahatchee’s current Midwest contingent. Cole has toured with Katie’s favorites Bonny Doon and played in her short-lived country project Plains. Missing in action at the moment are bassist Eliana, a classically trained L.A. resident who everyone calls Ellie, and Chicago-based drummer Spencer Tweedy (a sometimes collaborator with his father, Jeff). The spring Tigers Blood tour marks this band’s first time playing together, and Katie had to make sure all the musicians knew: She does not like to talk onstage. “I like to keep a very quick pace,” Katie says. “I’ve had to go to each of the boys and be like: ‘Stay sharp. We’re gonna move fast.’”

Night after night, the band takes the stage to hand-picked entrance music, “Southern Girls” by Cheap Trick: “All you Southern girls got a way with your words, and you show it!” The set starts with Tigers Blood opener “3 Sisters,” a slow burner that roils and simmers before elegantly exploding with the friction of its two characters, the poet and the outlaw, bound by history, separated by time. Katie steps off her platform, bites into the phrase try to justify as she tosses one of her endless stash of kc caps into the crowd—her own initials and those of Kansas City, her adopted home base since 2018—always to cheers. When Waxahatchee performs, certain tricks work in Fort Worth, Oklahoma, New York, anywhere: how the deep pause in “Ruby Falls” before Look at us silences the room, how the crowd screams for back home at Waxahatchee Creek, or when the band dives straight from “Ruby Falls” into “The Wolves” like an immaculately sequenced DJ set that makes you hear both songs anew.

In the green room after the show, I sit on folding chairs and talk with Reena Upadhyay, an early bassist in P.S. Eliot who first met the Crutchfields at Cave9. Now she works as a nurse, has a young son who is a huge Waxahatchee fan, and remains one of Katie’s close friends of two decades. “Even at fifteen years old, in her lyrics, she said the shit we were all thinking in a way we could never express,” Reena says with pride. I wonder aloud if there is anything Reena feels she can hear in Katie’s music that others maybe can’t—secrets in the songs she feels privy to due to their long friendship. “Oh yeah, all her shit about her family,” Reena says. “Her sisters are mentioned constantly—‘3 Sisters’ is clearly about her, Allison, and Sydney,” Reena explains, her sureness starkly contrasting the reviewers who sometimes characterize Waxahatchee’s poetry as inscrutable. “Katie writes from her heart,” Reena says. “If you know her well, you know exactly what she’s writing about.”

Knowing Katie only half as long as Reena, and not nearly as well, I also felt I could hear pieces of personal stories in Tigers Blood that intensified its emotional impact each time I listened. As a music journalist, I’m often negotiating these lines: What is the value of knowing what a song is precisely “about”? Does giving too much credence to context undermine art? Does doubting the value of context undermine journalism? I respect the mystery of art. I also prize meaning. In a world where songwriters are often too willing to neatly narrativize their music, it’s been impressive to watch Katie’s songs resonate so widely while retaining some appealing ambiguity. However, I felt strongly in this case that seeking more context, particularly regarding her lyrics that grapple with addiction and codependency, could be purposeful, grounding them in reality. Before the tour, I asked Katie if she’d be willing to dig a bit deeper into the stories behind those songs. She said she had already been thinking about it. She wanted to check with her family first.

MEMPHIS

In the perpetual forward-motion adrenaline rush of tour, the daily rhythms are steady. At night on the bus, Katie burns the same leather, cedar, and iris–scented incense that set the tone in the studio for Tigers Blood. Colin puts orange gaff tape over the interior lights to soften their harsh glow. Clay is the curator of the tour bus library, which includes Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, and a New Age self-knowledge guidebook belonging to Katie titled Human Design, among others. (On the bus one night, post-gig, while wearing a Mazzy Star shirt and feeding popcorn to Ernie, Katie explains to me that, according to Human Design, we both possess the “energy type” of “manifestor.”)

We sleep on the bus (or try to) and wake in a new city. We locate the venue’s entrance each morning, find the green room, use its bathroom to shower. There is a choreography to these bus-dwelling days that becomes innate: flipping a lock near the bus’s door to open the cab below to retrieve suitcases, carrying them through the heat, the slow emergence of the group, everyone knowing their part, respecting the signs on every bus- and dressing-room door reading puppy dog inside: be mindful of doors.

“It’s like Almost Famous—you’re comin’ on the road with us!” Katie had joked on the phone before Birmingham, a line echoed by nearly everyone I told I was going on tour.

“Have you ever seen The End of the Tour?” I asked her, also joking, naming the David Foster Wallace biopic based on the road-trip interviews for a never-realized magazine profile. Katie loves it; she insisted I read the book of Rolling Stone transcripts that the film was based on, David Lipsky’s Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, which I ended up bringing on the trip.

I had been leading to another question about Wallace: I was pretty sure the late Midwest recluse makes a cameo in her Tigers Blood song “Ice Cold,” on which she drawls the words, “This is waaaater,” stretching out the syllables of the last word to ripples at the top of the second verse. When Katie confirmed my suspicion that the lyric references the author’s empathic 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech of the same name, the detail felt like a skeleton key unlocking some bigger Tigers Blood themes. A lot of that speech is about how what we pay attention to ultimately decides our lives, a heavy truth in a world where attention is such a consequential currency that we are constantly at risk of losing. The Wallace speech opens with a parable about a fish in water; the lesson is that the most important realities are often ones that are the hardest to see and talk about. Profound choices lie within the mundanity of what Wallace calls the unspoken parts of adult life—“boredom, routine, and petty frustration”—all subjects of Tigers Blood songs. Katie describes “Ice Cold” itself as a song about “holding onto some old values of what it is to be an artist” and calls it “so existential.” But, zoom out, and Tigers Blood as a whole becomes a tapestry of subtle gestures toward Katie’s current ethos of life, in which questions about attention—how you control it, where you direct it, the links between tedium and awareness—form the ultimate prophecy of what life will be and how free you might feel in it. In disciplining her focus, she says, “I have a strong desire to keep everything really small.”

“Something about that speech is trying to hardwire people to have what is, to David Foster Wallace, this very obvious perspective, when it feels like everyone in the world has the opposite perspective and it’s sort of frustrating,” Katie adds. “I always felt inspired by it and how, if you can just shift your thinking ever so slightly, you might actually see the world in a way that makes you way more happy and functional.”

My tour reading material also includes Crimes of the Heart, the Pulitzer-winning 1979 play by Beth Henley from which a simmering Tigers Blood ballad borrows its name. It’s about three sisters in Mississippi, the Magraths. For Katie, Henley’s story is also subtly tied to her song “3 Sisters,” which shares a title with a different play by Chekhov. In Crimes of the Heart, the two older sisters rally in support of the youngest, who finds herself in trouble after shooting her husband. None of the sisters are “good” in the way one might expect of female characters. “As a songwriter in my twenties, I think there was a part of me and my persona that was a little bit righteous and rigid about people being flawed,” Katie tells me. “As I age, what’s interesting to me is that I am so flawed—we are all so flawed. There’s so much contradiction in [Tigers Blood]. I’m like, ‘Take my money, I don’t work that hard’ [on “Evil Spawn”] and two songs later, ‘I get home from workin’ hard.’ I’m consciously contradicting myself, because I think that’s human nature to do.”

Having grown up on stories of complex Southern women, Katie says Crimes of the Heart reminded her of the Dolly Parton and Julia Roberts tearjerker Steel Magnolias, her favorite movie as a kid. “When I think about this newer era of my music, I feel like, in all these different ways, I’m returning to myself before music,” she says. “Sobriety kind of reconnected me with country music. So much of my identity is wrapped up in what I’ve made, and what I do—and who was I before that?” Reflecting on Crimes of the Heart suggested an answer. “I am one of a group of three sisters,” Katie says, “and I have my own complicated relationships with them.”

West Memphis is overcast. Gazing over the Mississippi River from the other side, Katie and I stroll down a grassy walking path along the water. She’s wearing a mint-green, mid-’90s R.E.M shirt and holds Ernie—who I learn is named after the haunted Memphis bar Earnestine and Hazel’s—by a bubblegum-pink leash.

We are not far from the famed daily procession of resident ducks at the Peabody Hotel, where, as a child, Katie stayed with her family on spring break trips to Memphis. Those excursions were instigated by her mom, Tracy, a music enthusiast who wanted her daughters to visit Graceland and the National Civil Rights Museum. At home, she showed them musicals like Singin’ in the Rain and Bye Bye Birdie; also on the collective Crutchfield family mixtape back then was Johnny Cash, the Chicks, Alan Jackson, Shania Twain, and Elvis. (Not to be forgotten, either: the middle school talent show where Katie belted out the Fugees’ “Killing Me Softly” and solidified her tween reputation as a powerhouse singer.) Katie’s dad, Rob, is an insurance broker who Allison described to me as “stoic” but “a very good communicator and very unafraid of emotion.” They once took a childhood trip to his sunny, small, palm tree-lined Florida hometown outside Orlando, called Saint Cloud—“The houses were the exact same but different colors, these teeny cracker-box houses,” Allison told me—decades before it became the namesake of Waxahatchee’s biggest breakthrough.

Photograph of Katie and Allison by Tracy Crutchfield

As Katie and I walk along the Mississippi River, she points our eyes toward the bridge where a significant part of that breakthrough unfolded. In 2019, when she was nearly finished writing Saint Cloud, she and Kevin took a trip to Nashville, then visited Birmingham, before driving through Memphis on the way home to Kansas City. Right as they were leaving Alabama, she started hearing, within her, the loping melody to “Fire.” “It was unlike anything I had really written and it stuck in my head,” Katie says. “It was a really inopportune time to focus.” She held the tune in her mind for hours while driving before she could get it down. “I just kept singing the chorus in my head and humming it. I felt like: If I don’t stay really present with this melody, I’m gonna lose it, or it’s gonna change, it’s gonna lose whatever potency it has.”

A prayerlike anthem of self-respect, “Fire” became her poppiest song, unfolding slowly at first, a negotiation with herself: “If I could love you unconditionally I could iron out the edges of the darkest sky,” she sings, describing the throes of growth as the second verse crests, “Will you let me believe that I broke through?” She wrote lyrics in her head on the fly, jotted some down when they pulled over for gas, then got it all on paper when they stopped for the night in Jonesboro, Arkansas. The first verses were literal: The sun is setting and it’s reflecting this orange, fiery hue off the water. West Memphis is on fire. “West Memphis is literally right there,” she says, pointing to the unassuming peninsula known as Mud Island.

“When I first got sober, there’s just so much anxiety and wrestling with yourself that you’re doing, it’s this constant thing and it bleeds out into your life and spills into your closest relationships,” she explains as we walk on the river path. (Kevin suddenly jogs by; Ernie, on her leash, adorably tries running after him.) I ask what the process of getting sober looked like for her, if she did AA, which she declines to discuss, honoring the anonymity of the program. “I practice the Twelve Steps—that’s been a big part of my life’s journey,” she says. “I had a lot of support around me. At that point, I had tried to quit drinking maybe four or five times, or more. I just had this crazy Saturn Return thing where I left Philly, I had a new partner, I had a couple of really great new influences in my life, and I left some old bad ones behind. It changed everything for me.”

Among those positive new presences was Brad Cook, her producer since 2018’s Great Thunder EP, who brought more light to her sound—and banjo and pedal steel—and who has become one of her closest friends. More than ease or aesthetics, Cook instilled in Katie an even deeper personal conviction that feels almost mystical when either of them try to describe it. “All of Brad’s instincts around my songs have changed my whole life,” Katie says.

When I call Cook up at his North Carolina studio a few months after my trip, Katie is about to put out “Much Ado About Nothing,” another poetic banger they recorded over the July 4 weekend. “I spent like two hours in my garage last week listening to it on repeat smoking weed and crying,” Cook says. “Katie has seen me cry so many fucking times. I cry when she’s doing takes and I cry when I’m listening back . . . I’m a big fucking dude in the room, crying.” (Watching them play “Much Ado About Nothing” months later on The Tonight Show underscores why; the song is as “crushing” and “visceral” as its lyrics suggest.) Cook believes that such vulnerability can aid the process of shepherding highly emotional music into the world. “I try to make people feel safe and seen. That’s really the gist of it. The technical part of making a record, to me, is relatively easy.” Cook peels all layers back to center only the song, Katie’s essence and singing. “Her voice is so emotive, it does something to me that I can’t really explain. It’s an endless muse for me.”

I ask how that all played out the day they tracked “Fire.” It was the first Saint Cloud song for which Katie recorded vocals—at Sonic Ranch, the desert studio in Texas where she also tracked Tigers Blood—and the version on the album was her first take. “At Sonic Ranch at the time, they would have had a probably $30,000 vocal mic,” Cook remembers. “It’s a booth; pressure’s on. I could see she was getting in her head about it, and I was like, ‘Let’s do this. Just blast through it’—I made this up—‘because we need a new scratch right now. Sing it once, we’ll do these harmonies, and we’ll get lunch and move on.’ And she did.” There’s the take. Cook was trying to show the virtues of capturing a natural performance. “Since that day, I don’t think we’ve done more than three takes of any one song. Usually it’s one or two, and it’s incredible. Now she’s one of the most confident singers I know, in any environment. Confidence isn’t something you strive for, it’s not something you reach for. It comes from a place of being really present and relaxed. It’s like an acceptance.”

“Fire” anchored Saint Cloud like an epiphany, introducing a clarified new era of Waxahatchee; by Katie’s estimation, her audience doubled. She shared stages with Sheryl Crow, Jason Isbell, and Haim. She moved to the bus; she bought a house. Could she sense “Fire” was special while holding it? “Yes, more than I ever have in my life. More than ‘Right Back to It,’ more than any of the other songs on my new record.” In its own way, “Fire” was a logical step from the scorched-earth feeling of her previous album, 2017’s eloquent alt-rock kiss-off Out in the Storm; in the music video, she paces the side of a highway, then sets pages to flames.

“Fire” wasn’t just the signature song of her early thirties: It is a song about the possibility of a breakthrough, capturing the energy of the precipice of something new and huge, the process playing out in its slow bloom. A line in the sand, a before and after, burning down the past to attend to the flame in yourself—it’s all there. “Fire” itself is like a bridge she crossed, and it remains an invitation to cross your own.

Almost every lyric is grounded in the senses: the tactility of a coin, the sound of a siren, the taste of sugar, the smell of dust, the sight of a smile.

It wasn’t just her own past Katie was running from.

“I had two big problems in my life that needed to be addressed,” she says. “Addiction issues of my own, but then, codependency. Specifically with my younger sister.”

Six months after her friend Tripp’s death in 2011, Katie learned her younger sister had begun using the drug that killed him. It was an overwhelming fact she began to face, alongside the loss of Tripp, on Cerulean Salt. She’s processed their relationship across her songbook ever since. Saint Cloud included the dedication “For Sydney,” and the anguished Tigers Blood ballad “365” is a stark plea about “learning to have some detachment” in what became their unmanageable dynamic, setting a boundary for the sake of their mutual survival.

When we first spoke for this story in the spring of 2024, Katie had been out of touch with Sydney for a little over a year. But through letters from Sydney to their parents, Katie had learned that her sister is currently in recovery, and doing well. Katie’s protectiveness of her sister foregrounded all of our conversations. “For a long time, I was the very first person on the very frontline with her,” Katie tells me. “For so long, everything was: Drop everything you’re doing, this is an emergency, I have to go straight to her and help her. I have to fly from wherever I am.” (She later clarifies that her parents were ultimately on that frontline longest.)

The image echoes through the first moments of “3 Sisters”: “I pick you up inside a hopeless prayer,” she sings. “I see you beholden to nothing.” When Katie speaks about the song in 2024 she embodies its stoicism. She calls it “a poetic statement” with “a lot of different stories woven in,” but says that, when she zooms out, it encompasses “the pain of being so, so very close with somebody, and the frustration when somebody you care about so deeply makes a choice that you don’t agree with,” and how “all you can really control is your own feelings.” Each line rings with that gravity. Katie describes the lyric “I’m defenseless against the sales pitch / Am I your moat or your drawbridge?” as a “really transparent statement on enabling. It’s about feeling helpless and unclear about what action to take to assist somebody who’s struggling.”

I bring up another line, “It plays on my mind how the time passing holds you like pocket change.” It sounds to me like a reflection on how the world has treated someone recklessly, right in the hard phonetics of “pocket change.” When she first sings it, earlier in the song, the lyric exudes mercy: “It plays on my mind how the time passing covers you like a friend.”

“The world has spared you,” Katie explains. “We’ve watched so many people not be spared, and you have been. And what a blessing. But also, how does that happen? Time’s jostling you around, time is fucking with you, but still, it’s holding onto you, and you still exist.”

The title track is the last song Katie wrote for Tigers Blood, a wider lens on her and Sydney’s relationship, and a virtuosic piece of writing. Almost every lyric is grounded in the senses: the tactility of a coin, the sound of a siren, the taste of sugar, the smell of dust, the sight of a smile. The title image refers to a shaved ice flavor mixing strawberry and coconut that was once a family favorite. That childhood symbol doubles as something wilder shared by blood, just as the song is built on opposing truths—innocence and experience, sweetness and devastation, honesty and opacity, unruliness and dignity—and makes their tension soar. The scenes switch from the mess of the present to a past when they’re young, laughing in the front seat of a Jeep with red syrup–stained teeth.

“Held it like a penny I found / It might bring me something / It might weigh me down,” Katie sings on the chorus, which swells into a singalong toward the end of the recording, as it does every night on tour when Good Morning crash the stage. The “Tigers Blood” chorus is a miracle lyric, one anyone can hang onto to stay afloat in the depths of a vexed relationship in flux, loving someone but accepting the necessity of keeping them at a distance.

“This relationship with this person is two things at once,” Katie says. “It can be so magical and one of the more significant relationships in my life, and I also completely drown in it when things are bad.” As we discuss how the campfire-style vocals were inspired by Rilo Kiley’s 2002 song “With Arms Outstretched,” I recall a scene she’d described to me years ago: Katie, Allison, and Sydney as kids standing front row at a mid-aughts Rilo Kiley show, singing along, tears flowing.

Tigers Blood is rooted in terrain that feels tilled by the maturity of one’s mid-thirties, wise enough to hold multiple truths; as the writing weaves solemn realizations with youthful joy, the mix of light and ache becomes viscerally heartbreaking, but also exalted and beautiful, as complicated as real life. “There’s this tender, compassionate part of me that’s remembering that person as a kid, and remembering pain they experienced at this innocent time in their life. And there’s all the anger and resentment that’s happening right now. Internally, that’s what those experiences really feel like. All these emotions come up at once.”

Last spring, Katie told me she had plans to write to Sydney; she wasn’t sure if her sister had heard the record yet. “I mean, a lot of Saint Cloud was about her. She would be like, ‘Oh, another bunch of songs about me?’ No part of her would be shocked.”

Waxahatchee tour photographs courtesy the author

TULSA

The Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is a three-year-old shrine to one of the most elusive minds in music history. It was a virtually unspoken decision that the entire Waxahatchee touring party would spend the hours before soundcheck paying a visit to the Bard’s archives, snapping photos of his lyric sheets and fan mail and Newport leather jacket, the detritus of a life that paved the way for Lucinda, Fiona, Joni, Gillian Welch—so many of Katie’s most monumental influences. Strolling the few desolate blocks over from the bus, Katie tells me her favorites are the mid-’60s oblique pop classics and Nashville Skyline; at the museum she lingers in front of a display showcasing the note George Harrison wrote to Dylan after that 1969 album’s release. Up the stairs that say i’ll let you be in my dreams if i can be in yours, Katie and Kevin agree their favorite item in the museum is a letter Johnny Cash wrote to Dylan in which you can sense the country icon really rising to the occasion of pen-palling with a then-emergent pop-literary great. The recent announcement that Waxahatchee will join Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson on tour this September felt like a rare instance of the universe getting something right.

If the tour’s highways are like veins, they were all leading to Cain’s, its beating heart, a spacious century-old Tulsa ballroom with wooden beams and high ceilings lined by portraits of country icons like Hank Williams and Roy Acuff. Crutchfield barn burners like “Line of Sight” and “Burns Out at Midnight” just belong here. “I said from the beginning about the aesthetic of [Tigers Blood]—and I meant for the visuals, but it’s kind of true of the music, too—I wanted to be like a feminine, elevated bar band,” Katie says. I overhear Ellie call Waxahatchee “the greatest bar band in the world!” They were born to play Cain’s, and the crowd is an especially vocal one: “Album of the year!” someone screams mid-set.

Earlier that morning, news broke that the Chicago indie rock icon and legendary audio engineer Steve Albini had died at sixty-one. The news hit hard. During the encore at Cain’s, Katie and Kevin cover “Farewell Transmission” by Jason Molina [Songs: Ohia], recorded by Albini at his studio Electrical Audio in 2002, and dedicate it to his memory. Katie and Kevin have covered Molina often, usually his biting mini-anthem “The Dark Don’t Hide It.” With his DIY origins and raw embrace of country, Molina became an avatar for Midwest isolation before his death from alcoholism at thirty-nine. “Farewell Transmission” is mysterious but elemental. The seven-minute song opens with a weeping pedal steel hook repeated throughout; it ends with an almost shamanistic portal to some other dimension, with cryptic lyrics that still communicate unmistakably about mortality and the threshold between this world and whatever backstage of reality is waiting beyond it. When Katie and Kevin first covered it in 2017 for a tribute single, Katie remembers meticulously writing out the lyrics by hand.

“‘Farewell Transmission’ as a song is such a behemoth undertaking as an artist,” she says after the show, sitting with Kevin and Ernie in her dressing room, which is mostly empty except for the dog’s pale-pink crate.

“I feel like that song is Shakespearean or something, its own magnum opus,” Kevin adds. “I was getting chills as we were rehearsing it.”

Quoting her favorite of the song’s lyrics, Katie recites, “‘Dust my feathers with his ash’ . . . ‘I’ll streak his blood across my beak’ . . . what the hell is he talking about?” This is effusive praise. “I feel like no songwriter has ever written about death better than Molina,” she adds.

“You once made the comparison to Townes Van Zandt,” Kevin says. “With both of them, you almost feel like you’re getting a message from a psychic . . . like they went to the other side and came back or something.”

For Katie, covering Molina was another creative awakening. “I’m curious if you remember this,” she says to Kevin. “When we did our tour together in 2017”—when they fell in love—“when I was playing solo, you said to me, ‘You’re a country singer.’ And that was like the lighting of the fuse for me. Shortly after that, we did these Molina songs. Hearing my voice trying to sing like him was sort of the first time where I was like: Now I hear it. I hear that I . . .” She hesitates.

“Am a country singer,” Kevin says.

Certainly, her country roots were always there: On early songs like “Misery Over Dispute” and “Chapel of Pines,” you could hear an eternal yearning, her voice pushing beyond its bounds with the teardrop grit of a universal jukebox. It’s a heritage she’s embraced with evermore assurance.

“In my mind, before that tour, I was like—Katie’s a Philly punk girl, more like Sleater-Kinney than Loretta Lynn,” Kevin says.

“Make sure you quote him on that,” Katie says.

“When we were doing the tour,” Kevin continued, “you would get up there and play every night, I was like, these are great country songs when you break it down. You had a blue dress on and you covered Lucinda. To hear you playing the chords on acoustic guitar, I was like, Katie’s a country singer. And here we are at Cain’s Ballroom.”

“After a country concert,” Katie says, laughing.

Cain’s green room is a separate building behind the venue, sprawling with a big kitchen table and an expanse of gravelly outdoor space. Before the show, the sky turned pink and everyone was gazing at it, drinking NA beers or Modelos, tossing a baseball. The gentle green-room revelry continues on after the gig; passing around an acoustic guitar, Spencer does “Cripple Creek Ferry,” Kevin does “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” while a guitar tech named Brandon Carnes destroys Clay at ping pong.

“The security guard at Cain’s was talking about how it gave him goosebumps to see everyone just hanging out, being friends, throwing the baseball, kicking the soccer ball around,” Waxahatchee’s tour manager Peyton Copes later tells me. “He said, ‘Lots of people come, and they’re just bummed out.’” On this tour there is little doubt that everyone feels lucky.

FORT WORTH

“The rodeo tried to buy out the show,” Peyton announces.

I’m one of the first to wake up on a sweltering morning in Fort Worth, Texas, and I go the bus’s front lounge area around 10 a.m. We’re parked on the street outside the venue. The window seems to frame the set of a Western.

The rodeo tried to buy out the show. What could these words, in this order, in this semi-grave tone, in the context of Waxahatchee, possibly mean? As each member of Waxahatchee rolls out of their bunk in pajamas, they get the news—The rodeo tried to buy out the show! The phrase becomes the morning’s refrain.

We’re in the cowboy district of a cowboy city in cowboy country. Cowboys inhabit every inch of sidewalk, every corner, working behind the counters of boot stores, singing from an ad hoc stage on the street, congregated into this Lone Star downtown of saddle shops, saloons, honky-tonks, something called The John Wayne Experience, and Cowtown Coliseum, which tonight is hosting the Professional Bull Riders World Finals directly across the street from the venue where Waxahatchee is booked. Bull riders are here from Brazil. Apparently, the rodeo tried to buy the remaining three hundred tickets to the Waxahatchee gig for undisclosed purposes; of course, no matter the reason, the move would have helped increase the rodeo’s own ticket sales. The concert’s promoter declined the offer.

“Where’s the rodeo?” Ellie asks, gazing out the window.

“You’re looking at it,” Katie replies.

“Like this town isn’t big enough for the two of us kind of thing?” Clay wonders.

I tell Katie it’s kind of a flex to pose a threat to the rodeo, which she begins to repeat to herself, “We pose a threat to the rodeo.”

“I’m weirdly flattered,” Katie concludes. “We’re happy to compete with the rodeo.”

After roaming the streets—where Ellie gets a flat-rimmed black hat that makes her look like a chic bandit; where Katie buys leather boots and a thrift shop Texas license plate that says the eye; where, a bit later, I will be handed a stack of free tickets to the undersold rodeo—we sit in Katie’s sleek dressing room and discuss the few Tigers Blood songs that grapple lightly, she tells me, with “music industry qualms.”

Both Saint Cloud and Tigers Blood end with trios of ambitious ballads that take big swings while slowing her pace, stretching her melodies to make complex stories sweep. The catchiest among them is “The Wolves,” with its impressionistic lyrics that seem to gesture toward the “touch-and-go” reality of a musician’s life and her “one-track mind” approach to making it work. Thinking about “The Wolves” brings Katie back to yesterday at the Dylan Center. Or rather, it brings her back to being on stage last night at Cain’s, playing “Ice Cold,” thinking about the Dylan Center. “Ice Cold” is her song referencing David Foster Wallace, and in the middle of performing it, she found herself tracing some possible commonalities between Dylan’s closely guarded privacy and the sentiment of Wallace’s speech.

“There’s all this stuff that’s sort of interpreted as this weird lore about Dylan: he’s never been to his Center before, he didn’t accept his own Pulitzer, he barely spoke to Obama at the White House. Even hearing him talk about people calling him a genius, and how it doesn’t feel right . . . I was having this moment yesterday thinking, That all feels like a genuine attempt to stay”—she thinks for a beat—“small. And regular, in order to make better art. Which is something I appreciate, and in my own ways put a lot of energy into doing the same.”

She calls “The Wolves” akin to this all. “We live in this time—in the music business, but all over—where there’s such a desperation for this perceived success. People are on TikTok! And people are creating content! And it’s like ‘more, more, more,’ this maximalist, excessive time of output, output, output. ‘The Wolves’ is about taking a different approach and not relating to that. I try hard to not be judgmental because people have lots of different reasons to want different elements of success. But even with the metaphor ‘There’s a lock on the door’—people are trying to hack their way in with an ax. They’re outside of the more traditional aspects of success and want to get in.” The song is about prioritizing creative integrity instead, which she’s managed via old-fashioned craftsmanship and a conscious two-decade slow burn. She sees it as no coincidence that she wrote what she considers her two best albums after quitting social media in 2018. (Today she doesn’t even use Google as a search engine, preferring DuckDuckGo.) “Since I have become more protective of my own attention,” she says, “I feel more attuned to myself emotionally,” a necessity of making autobiographical art. “It’s ultimately made me a more patient and compassionate person.”

Photograph by Molly Matalon

Every night during “Crimes of the Heart,” Katie sits on the stage’s edge; during “Hurricane,” she paces. On “The Eye”—Katie’s pristine ode to vagabond love among touring artists—she rings textures from her voice that are so exquisitely expressive, they induce chills every time. The band covers Lucinda most nights. After the encore, the house music always blares Iiiiiiii’ve been cheated! Been mistreated!—transfiguring the show’s high emotions into impassioned Linda Ronstadt karaoke. The glowing arches of the stage design look straight out of a mid-century variety show, and every night, post-gig, I watch the crew disassemble all twelve light bulbs, slip each one safely back into its own box.

Her bandmates wonder how she makes her hard work seem so natural. “I’m still in a phase of awe trying to wrap my head around the way Katie uses language, trying to understand how someone gets to the point where they have the command she has,” Spencer tells me, at a Texas diner that is also an antique store; framed Elvis clippings decorate the booths. “It’s one of the craziest magic tricks in all of songwriting—to use phrasing and rhyme in the way that she does while still being connected to so much meaning.” Cole highlights the rare alchemy in how she directs the band on stage. “The way she leads the band is really graceful and seems effortless, but she is clearly steering the ship. She can play an acoustic guitar with this loud band around her and totally drive it. It’s not just her voice or her guitar playing—her spirit is driving things.” What distinguishes her spirit? “Her willingness to look people in the eye,” Spencer offers.

When they started playing together after Saint Cloud, Ellie was taken aback by Katie’s voice: “In a world where so much of indie rock is indistinguishable… there’s this, I hesitate to say, grittiness,” she tells me on the bus. “There’s a lot of character and texture to her voice. A lot of music right now is being made to end up on Spotify playlists, which end up in cafes, and it’s like background music. There’s some pressure to have this velvety-smooth voice that’s just an unidentifiable, beautiful female voice. And with Katie’s voice, you feel that this is a person from a specific place, with all the warbles. She fits a lot of sounds into a single vowel. It’s very Southern.”

As I consider Spencer’s question about Katie’s command, I think of the decades. Watch her bloom from a nonchalant punk wanderer into a bonafide star across Waxahatchee’s two Tiny Desk Concerts, from 2013 to 2024; imagine the road in between. On this tour, the moving pieces of the all-day Waxahatchee production feel like a logical progression of her steady movement forward—writing for decades, crashing on floors for self-booked tours so long it hurt just to see the itineraries, honoring “the calling of ‘The Eye.’” (“To posses something arcane,” she sings on that mini-masterwork, “it’s a heavy weight.”) Her music and attitude are so lucid now, her performance so embodied, that confidence does become the show’s key. The shift was there on Saint Cloud, where certain lyrics could feel like deliberate inversions of her previous albums’ tentative emotions. On my favorite American Weekend song, she sings in almost a whisper: “I think I love you / But you’ll never find out.” On Saint Cloud she sings with forthright conviction: “Love you til the day I, love you til the day I, love you til the day I die.” She began 2015’s Ivy Tripp claiming “I’m not trying to have it all.” By Saint Cloud’s opener she knew: “I want it all.”

Waxahatchee tour photographs courtesy the author

HOUSTON

On my second-to-last day of tour, I sit with Katie in her bedroom at the back of the bus talking for two more hours. Her bedspread is covered in tulips, a copy of Molly by Blake Butler sits next to her pillow, and the incense burns through the afternoon.

After nearly a week of discussing mortality and recovery, philosophizing attention and communing with Dylan, charting her transformations and ambitions, it’s funny to realize how many of the same topics we are covering here, on her tour bus, at thirty-five, as we did a dozen years ago while sitting in her Philly bedroom in our early twenties. We discuss the Rilo Kiley influence on “Tigers Blood,” and how the toughness of the lyrics to “Crowbar” are inspired by our eternal hero Fiona Apple despite it being “this super jangly pop R.E.M. worship song.” We discuss the negotiation between rootlessness and her desire to be rooted. We probe the psychology of twinhood, parse the lyrics of deep cuts. We talk about generational differences and family, as we did back then; her early song “Rose, 1956” was about her late grandmother, whose spirit lingers at the beginning of “Arkadelphia”—another song for Sydney, and the hardest Saint Cloud song to write.

“Arkadelphia” was also the most difficult for her twin sister Allison to hear. Whenever Allison listened to Saint Cloud, she says on a video call a few months after my trip, “I’d have to skip it. It was really hard.” From Tigers Blood, it’s the title track that always makes her cry when she sees it live. “It makes me think of Sydney when she was little,” she says. “It really paints the picture: this is a person’s whole life.”

At the time of our conversation in September of 2024, Allison has also been out of touch with her younger sister for a year. The severity of the situation, and the pain of that distance, are clear, as we speak, in the ache of her voice, in her tears. “Anybody who has family or people close to them who are addicts are so familiar with that feeling of having to have a full wall up. But never giving up hope about somebody,” she says. “We are in such a true health crisis with addiction and with fentanyl, with heroin addiction and opioid addiction. People can be really ignorant and really callous, and they can think of people who are struggling with addiction as a number or a statistic. They can look at the behavior and not think about the fact that this is a person who had a childhood, and who has parents.”

I ask how she felt hearing “3 Sisters” for the first time. “Katie’s experience is different than mine, but at the same time, it’s shared,” she says. “And in some ways, I think it’s shared in a way that nobody can understand. My parents, anybody. It’s within the three of us. And so to have . . .” She trails off a bit; her voice wells. “I mean, it’s such a beautiful song.”

The line from “3 Sisters” that gets Allison hardest is “I don’t see why you would lie; it was never my love you wanted.” “For people who love addicts, there is a lot of manipulation that you experience, and there are a lot of false starts,” she says. “That’s a very succinct line about love and manipulation. I know firsthand what Katie has experienced with that.”

In music, the “Crutchfield sisters” have been a known entity for well over a decade; the New York Times first profiled Katie and Allison together in 2012, and five years later credited them with shaping the sound of the best rock music today. “People only really know about two of us because Katie and I have always worked together,” Allison continues. “But there’s always been three of us, with one of us kind of out of the picture. So to listen to a song like ‘3 Sisters’—it’s hard. But it feeds the part of me that knows, at some point, there will be three of us again.”

Everyone I speak to in Katie’s orbit—from bandmates and collaborators to family—agrees that her focus and devotion, structuring her life in service of her vision, are inspiring. “Katie’s one of the few people I’ve ever known who walks the walk all the time,” Brad Cook tells me, citing her post-Saturn Return ascent as proof that “you just got to put your head down and do the work and not compete with anyone in the world but yourself.” Being in proximity to her world, you want to accept that same challenge, stare yourself in the eye, pay attention. And the closer I get, the more I see how the realities behind her songs have necessitated some relative inscrutability in her delivery and reserve in her daily life, a self-protectiveness allowing her to wade into the deep end musically.

What I see clearer still is the extent to which Katie has become a kind of avatar for creative growth for so many people around her. When I hear Saint Cloud’s “Ruby Falls,” another tribute to her late friend Tripp, with its middle section alluding to Patti Smith and her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe—a tale of “two young creative people who kind of want for nothing other than making stuff together and inspiring each other,” Katie says of “Ruby Falls”—it feels like a telling connection to a towering patron saint of artistic process. “Sometimes it feels like you have to build an altar and sit quiet and wait for it to come,” Katie said of her own process, when we spoke before tour. “When it’s coming, you just have to receive it. It is that mysterious to me still. The only thing that’s less mysterious is that it will come.”

I will leave tour energized (paradoxically, it must be said—sleeping on a bus is surely yet another mysterious process) and back home, I’ll try hard to hang onto the feeling of renewal. I’ll attempt to recapture it by lighting the leather-scented Tigers Blood incense, by playing Katie’s albums and those at her altar of influence like Townes and Emmylou—by employing every tool I have to hone my focus and feel the glow that surfaces when you engage more deeply with yourself. (“You caught the bug,” Cook jokes, when I tell him as much.) Katie and I will get in touch again in the fall; that same month, she and Sydney will finally talk on the phone. Around Tigers Blood’s first anniversary, I will get a chance to call up Sydney myself.

From the moment she gets on the line, speaking from where she now lives and works about an hour outside of Birmingham, I’m immediately shocked by how identical Sydney’s voice sounds to Katie’s and Allison’s, exuding the same warm candor and rounded cadences, albeit with an amplified Southern drawl. “It was really cathartic,” she tells me, of listening to Tigers Blood last year. “Hearing those songs did something to me emotionally. I don’t exactly know what emotions, but there were a lot of emotions. It made me feel closer to one of my best friends in the whole world, my sister, knowing that it wasn’t quite time to talk yet.” Sydney was in treatment at the time of the album’s release, without a phone, and remembers using a TV to check for new uploads to the Waxahatchee YouTube channel during moments alone. “Since it had been a minute since I’d spoken to her, every time a new single was put out or anything, I held onto it real tight.”

Sydney inferred right away that some Tigers Blood songs were about her and Katie’s relationship. “Knowing that I was working on myself, it didn’t feel hurtful or anything. It more so felt like, ‘Okay, this is a relationship I really, really need to take my time with and put care into,’” she says. The phrase “tigers blood” made Sydney think of her dad, and his perennial go-to flavor at Sno Biz, the local shaved ice spot. She says the whole album felt like opening a time capsule of her and her sisters’ shared childhood in the deep South. “Growing up with them as older siblings, I felt like I always had the upper hand in life,” she says. “It was like having two built-in best friends who I looked up to and always thought were so cool. We all had the same taste in music and clothes.” She laughs, calling up a timeless trope of sisterhood: “The root of all Crutchfield arguments was over clothes.”

Sydney remembers the fated day in the early 2000s when all three Crutchfield sisters went over their mom’s best friend’s house to peruse some stuff set aside for a garage sale, including a bunch of R.E.M. and Cranberries greatest hits CDs that ten-year-old Sydney proceeded to “religiously” put in heavy rotation for school bus Discman sessions. “And there was some kind of old black electric guitar,” she says. “Katie went for the guitar. I remember us going home and Katie—I don’t know if it was that day or within the next couple weeks—Katie teaching herself how to play some songs. She was learning how to play the Hole song ‘Malibu,’ I remember her strumming that.”

Two decades later, Sydney is conscious of how pieces of her and Katie’s experiences live inside the poetry and nerves and chords of Waxahatchee songs. “Katie’s writing is very subjective, I would say, a lot of times. But I think hearing those [Tigers Blood] songs was a good thing for me,” she says. They offered her perspective. “Addiction can be tricky—you can be really aware of the pain you’ve caused, but still kind of be like, ‘Oh, maybe it wasn’t that bad,’ or ‘maybe I wasn’t that hurtful, maybe it’s really just affecting me,’ that kind of thing. It’s been good, especially in recovery, for me to hear any kind of effect that it’s had on my loved ones, to have that reminder of like, Okay, this is the good, the bad, and the ugly. This is what it looks like to other people.”

Near the end of our call, the conversation turns toward the broader question of what value we might get as music fans, or just as people, from knowing the deeper stories a song might contain, and how those stories might fortify a song’s potential to connect us to one another. “I think that’s why music can be our lifeblood,” Sydney says. “What makes people thrive is being in conversation with other human beings.”

“Having a little bit of backstory would be kind of nice in a way,” she adds with what sounds like a hint of amusement. “Because [Katie and I] are so close, I can kind of unpack certain lyrics. But then, sometimes I think only she really knows. And I like that about her writing.”

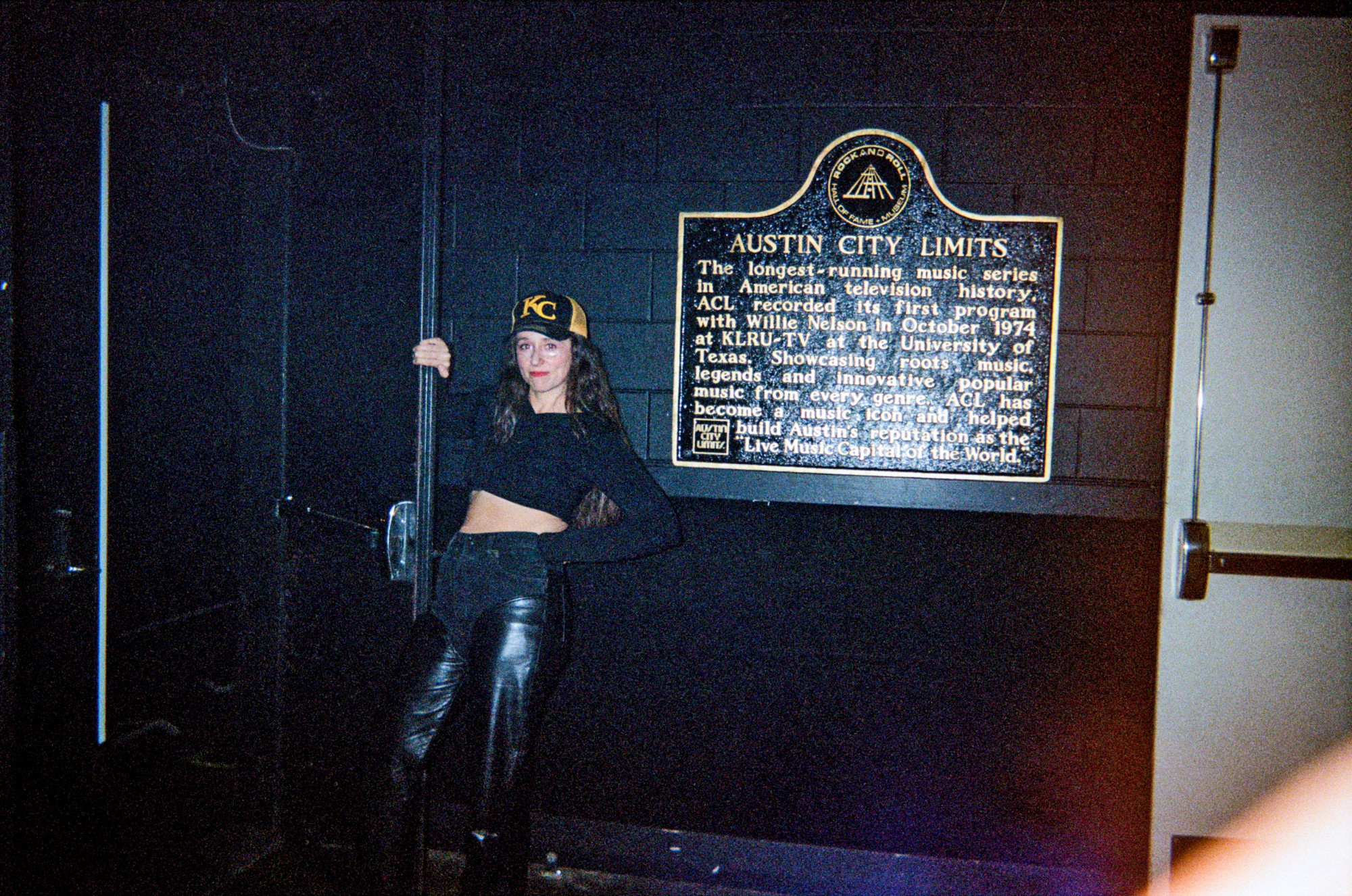

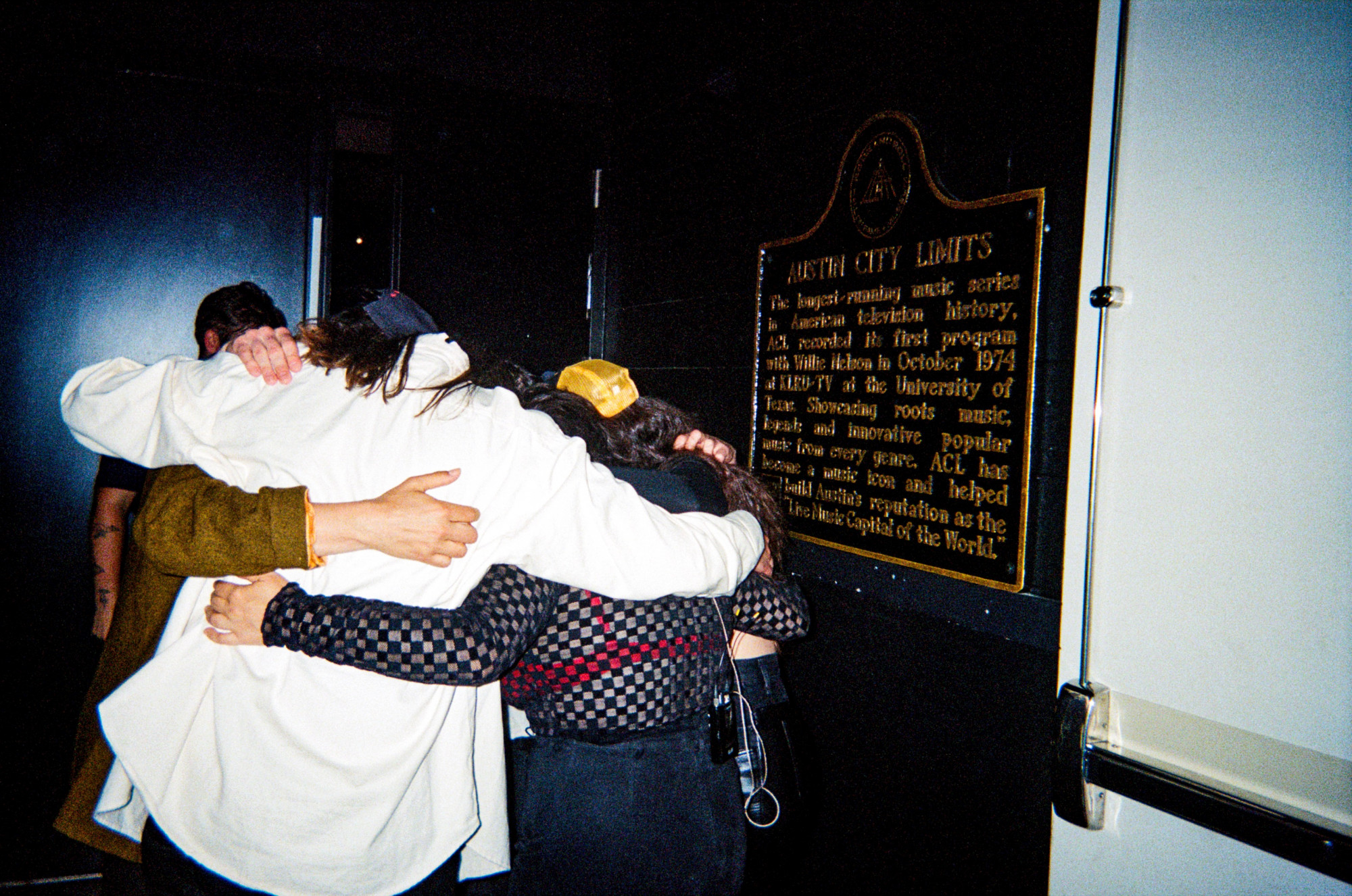

AUSTIN

The end of the tour, for me, is Austin’s Moody Theater, the biggest show of this stretch, presented by Austin City Limits. Earlier that day, Katie had briefly gone MIA; turns out she went shopping, picking up a copy of The Artist’s Way for a bandmate. She told me she had to have “the most unstimulating day” in order to “launch myself out of a cannon” on stage.

In the green room lined with gilded live photos of Dolly and Loretta and R.E.M. and Neil Young, Katie warms up her voice using a cocktail straw; she shows me the tube of glitter she uses to sparkle her eyes every night. I snap a picture of the band in a huddle before they walk out on stage, in eyeshot of a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame plaque reminding us of Austin City Limits’s history as the longest-running music series in television history, beginning with Willie Nelson, in 1974. First, I watch this Waxahatchee set from the very front of the crowd, like I have for so many years. Halfway through I race up to the balcony. Widening my view, I watch three packed tiers of fans singing along to the final song:

I held it like a penny I found

It might bring me something, it might weigh me down

You got every excuse but it’s an eerie sound

When that siren blows, rings out all over town

When I hear “Tigers Blood” now, I think about the last page of Crimes of the Heart, the play Katie recommended about a vexed family of Southern sisters. The Magraths are congregated back at home on account of Babe, the youngest, who shot her husband. (Her reasoning: She wanted, herself, to live.) They have suffered familial deaths, lost love, bad reputations, and shattered dreams. But, amid the violence and strife, it’s the oldest sister Lenny’s birthday, and they’re together, eating cake. Lenny makes a wish on a candle and her sisters demand to know of what.

LENNY: Well, I guess it wasn’t really a specific wish. This—this vision just sort of came into my mind.

Babe: A vision? What was it of?

Lenny: I don’t know exactly. It was something about the three of us smiling and laughing together.

Babe: Well, when was it? Was it far away or near?

Lenny: I’m not sure, but it wasn’t forever; it wasn’t for every minute. Just this one moment and we were all laughing.

Babe: Then, what were we laughing about?

Lenny: I don’t know. Just nothing I guess.

Meg: Well, that’s a nice wish to make. Here, now, I’ll get a knife so we can go ahead and cut the cake in celebration of Lenny being born!

Babe: Oh, yes! And give each one of us a rose. A whole rose apiece!

A great song is a hope to hold close. A little prayer, a vow to remember, a bid to leave home and go back changed. It comes, in the end, from life: it inhabits yours; it takes on its own. Singing Katie’s words, the song becomes the wishful penny, the sweet rose, the childhood tiger-blood portal to some kernel of innocence we might summon and hang onto like a lucky charm—in every note, every vowel, a promise.

Support the Oxford American

The Whiting Foundation will double your donation—up to $20,000.

Your donation helps us publish more work like the article you're reading right now. And for a limited time, every gift will be matched up to $20,000 by the Whiting Foundation.

Prefer a subscription? You'll receive our award-winning print magazine—though subscriptions aren’t eligible for the match.