ALEX MAR’S JOURNEY INTO THE OCCULT

By Caitlin Love

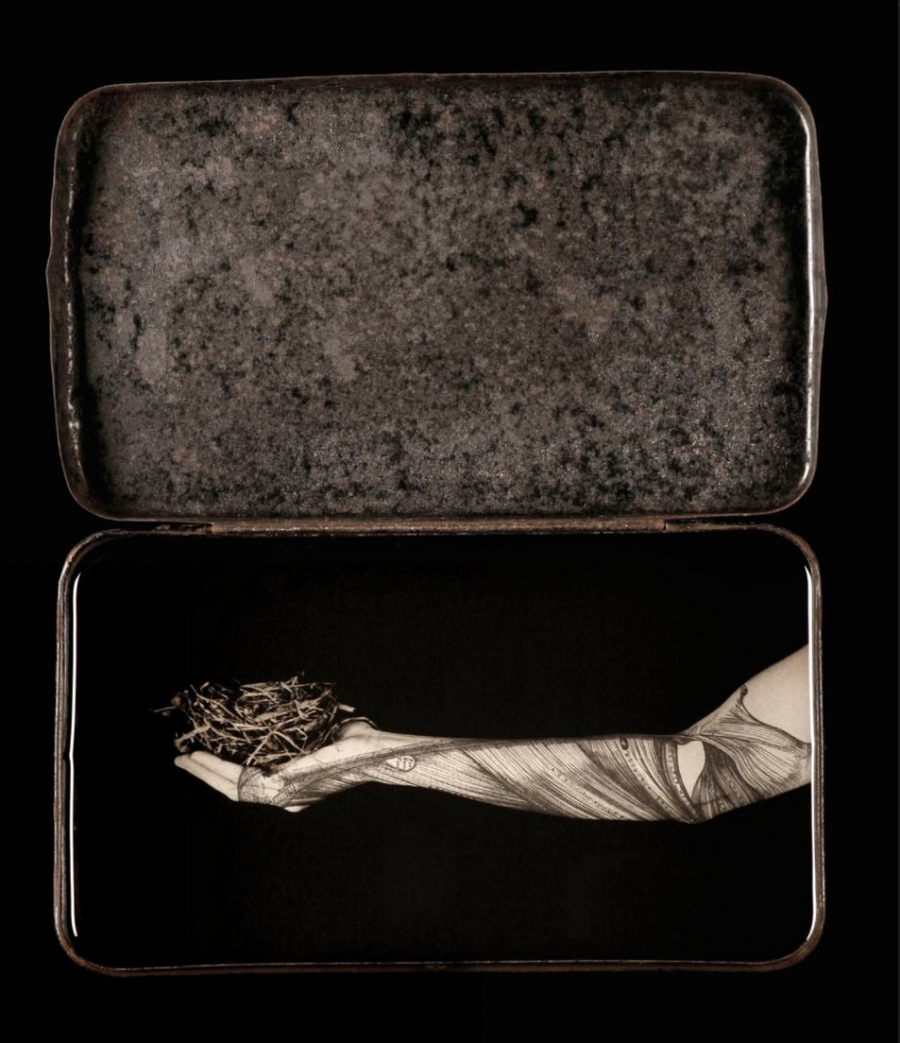

Courtesy of the artist, Heidi Kirkpatrick, and Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

Alex Mar’s work tends to angle toward the spiritual, examining religious lives or the End and what comes after. Her documentary, American Mystic—a lovely, lyrical feature that follows three members of different fringe religious groups—was released in 2010. In June 2013, she published a story in the Believer about a group of transhumanists in Arizona who “cryopreserve” their members’ minds.

In Fall 2013, the Oxford American published Mar’s “The Secret Life of Nuns,” about the Dominican Sisters of Houston, a work driven by particular curiosities: “Why would a woman make the very specific choice to marry God?” Mar wrote. “Why would she choose to live with his many brides and very little privacy and pooled resources . . . to set aside every personal need and closely held ambition in favor of the needs of others?”

The following year, Mar wrote about the practice of excarnation at a forensic anthropology research facility in Central Texas, where deceased people are laid out to decompose in the open air. Some of the dead are eaten by vultures; others are set under protective cages, their bodies safe to wither in the sun undisturbed. Mar notes that excarnation is a practice with historical precedent. Known as “Sky Burial,” it has been practiced by Tibetan Buddhists, the Parsis of India, and certain Native American tribes.

Mar is adamant that the through-line of these pieces isn’t “spirituality,” but “belief systems that are really specific in a way that forces the practitioners to deal with a life that’s not part of the mainstream.” The topics don’t necessarily concern religious communities but the spiritual choices of people. What leads a person to donate his body to science? Why would a woman devote her life to God? What does it mean to believe in anything at all?

Witches of America, Mar’s first book, published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux this month, follows this thread into the world of modern witchcraft. Mar studies the histories of Wicca, Feri, Ordo Templi Orentis, and other practices. Her journey becomes a personal one. She befriends a Feri priestess from California named Morpheus who leads her on a spiritual quest further into the occult. Eventually, Mar herself begins to practice Feri, studying with a priestess named Karina. She attends occult ceremonies in corners of America as disparate as a castle in the woods of New Hampshire and the thick, dark swamps of southern Louisiana. In a sharp and harrowing chapter deep in the book, she reports on a man in New Orleans who goes to graphic and disturbing lengths for his extreme cemetery magic. The book is propelled by Mar’s layered details and her rare and instinctive curiosity as well as her quiet graciousness toward her subjects.

She and I spoke about Witches just a few weeks before the book launch.

How does Witches of America go beyond the scope of American Mystic? Why did you feel the need to look deeper into witchcraft?

Well, first let me say that the documentary is really different from the book. The doc follows three people in their twenties who are part of fringe religious communities in very far-flung parts of the country. Witchcraft is only one component of the larger film, which is really minimal and lyrical; it’s kind of like a poem. And there’s none of me in it. Because of that, there’s also none of the kind of humor that’s involved in revealing yourself as an individual who decides to go on a journey—in my case, searching for witches and occultists all around the country. In the book, I’m acknowledging the awkwardness and the stumbles along the way as I try to get my own footing in Pagan communities. None of that is in the film.

This Pagan world is a discreet part of American religious history that hadn’t been told of yet, outside of very small snippets in books that are really for the community itself. There’s power in having a narrator whom you feel like you can relate to, especially if that person is asking you to come with them into what seems like really exotic and potentially alienating terrain. The world of witchcraft and the occult can seem either very intimidating or silly to some people, and I thought it was important for there to be somebody who the reader could latch onto and feel that they had something in common with. This helps make the reader willing to go along with you as you end up in late-night circles drinking from chalices and all the other good witchy stuff.

Courtesy of the artist, Heidi Kirkpatrick, and Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

I was surprised by how modern several of these traditions are. Even though certain founders, like Gerald Gardner, drew their practices from older traditions, Feri and Wicca only really developed in the twentieth century.

I make a distinction in the book between the word “witchcraft”—as it’s used to talk about folk witchcraft—and the witchcraft that I was interested in. Folk magic, traditions, superstitions are in the background of almost any culture. You could look at any family anywhere in the world and find a relative who does little things in the kitchen or hangs a special object in the window or above the door to the house. So there’s that way of using the word witchcraft, with a lowercase “W.”

Then there are different groups of magical traditions—Pagan religions—that go back all the way to ancient times. People think that witchcraft goes back to the beginning of time and you can draw a wobbly line all the way to today, and that’s just totally untrue. There are collections of spells that have survived that let us know what certain practices existed at a given time, and we know about rituals done to honor ancient Greek or Roman gods and goddesses. But what I was focusing on is something that’s only been going on in this country since, as you said, about the fifties. It can be traced back to the south of England, to Gerald Gardner and the very beginnings of what he called Wicca. And then that came over to the States. By the seventies, witchcraft was really spreading. Today, there are several hundred thousand, possibly as many as a million people in this country who call themselves Pagan or witches.

The big surprise for me is that some of the central characters in this movement are only recently deceased. Some of them are actually still alive today. And I don’t want to get too lofty about this, but on a technical level you could draw an analogy and say it’s like being around in the days of Jesus and his disciples. This was an opportunity for me to look at the architecture of the very first decades of a new religious movement, which was totally exciting as a journalist.

In “The Secret Life of Nuns,” you really just appear as a foil to the nuns, women who have dedicated their lives to the church and to God. But in your book, the “I” is very different. Your personal journey is at the heart of the narrative. What’s different in writing about yourself as opposed to your reported subjects?

Before completing this book, I never, ever, ever would have thought of myself as any sort of confessional or first-person writer. I enjoy a lot of first-person writing, but the idea of it for myself really grossed me out. Actually, when I sold the book to Farrar, Straus & Giroux it was with the sense that I was only going to have very peripheral involvement with the culture; I would be a lens through which the reader could experience these rituals and ceremonies. I realized really quickly that that was just nonsense. There wasn’t a way for me to dive into the question of what it means to believe in anything and the question of why someone would identify with an outsider religious movement—especially one associated with a word as scary as “witchcraft”—without also putting myself on the line.

Being in a ritual of any kind is also a really subjective experience. To pretend that there was any chance of objectivity would have been unfair and would have felt untrue. This is also related to something else about the topic, which is that writing about faith has got to be one of the most embarrassing things a person could possibly do. I mean, it’s just so mortifying. These are the things you would normally talk about only with your closest friends or your family because it’s so personal and very vulnerable.

How did you eventually resolve that problem of having to write about yourself? Were you responding to the subjects who let themselves be vulnerable to you?

Well, I already had a relationship with Morpheus—one of the central characters in the book—for a couple of years before I started this project. And she had never opened up to anyone publically in the way that she did to me when we were making the documentary. I was really impressed by her openness and I thought, if she’s putting her trust in me, trusting me to share some of her most private practices with a public audience, then I have to stop being a sissy. I think that most writers, at some point in their projects, realize they’re either going to push themselves all the way to the wall or they’re going to abandon the work.

There’s a kind of gimmicky stunt version of this book, which is the “Let me take you on these absurd, wild, dark adventures in witchcraft” version. Like, “I’m going to treat these people like some carefully contained outsider community that we can poke a stick at.” But that would ultimately be a pretty superficial experience, and it wouldn’t ask any questions that hit close to home. I’m sure there’s some version of that that could be absurd and entertaining, but I have no interest in it and it’s not how I feel about this community. I developed real relationships and I pursued this topic out of personal curiosity. I wanted to end up in these huge rituals, and I knew that, at some point, I wanted to train in a specific witchcraft tradition. There were moments when it definitely took a toll, and it was an exhausting and confusing experience at times.

Courtesy of the artist, Heidi Kirkpatrick, and Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

When you started the project did you intend to be trained as a witch?

No. I just knew that I wanted to know more. When I was making the documentary, I was involved only from a distance. With film, there’s the physical barrier of cameras—unless you are going to be on camera yourself, which I had no intention of doing. So there’s always a kind of ring of fire between you and your subjects. And we also couldn’t film any rituals, mostly because that’s just seen as being really tacky. Plus, a lot of people involved in witchcraft tend to think that kind of interference prevents real magic from being possible. I also just thought, Okay, this is interesting as material for a film, and that was it.

It was my surprising personal connection with Morpheus that really drew me in. She’s funny and smart and fascinating, and we just got along. She doesn’t fit into many of the cliches that I had in my mind of what it might mean to be a Pagan priestess. So I wanted to know more about what she knew that I didn’t know.

At some point, I decided that I was just going to do whatever attracted me. Whenever I felt bored, or like this isn’t for me, I shifted course. I let my own nose lead me. In this way, my relationship with Morpheus was an important clue. What is it about Morpheus’s practice, or her, that points me in the direction that I want to explore? And that took me to Feri, and Feri took me to Karina and around the same time, I ended up in New Orleans and became involved with, essentially, Aleister Crowley’s disciples.

In a sense, you did the exact same thing that any modern witch today would have to do to seek out a tradition or practice. All your characters come to witchcraft by seeking it instinctively. You were following the same pattern they were.

Completely. I felt that that was very genuine, and it was the way I’ve seen other people go down this road.

Did your friends or family ever think you had gone too far?

During the three-or-so years that I was really in it, my friends and family outside of the Pagan community only knew that I was working on a book. And they knew that the book was about witchcraft in America, and that I was traveling a lot, but they just assumed that it was the same level of engagement of work I’d done for magazines. Like when I lived in a convent in order to write about the Dominican Order in Texas. I think part of the reason for that is that I didn’t totally know how to reconcile both worlds. It takes a lot of explaining to not worry your friends that you’ve become involved in a secret society.

At the end of the day, I’m a writer above all other things. I always knew that I was writing this book and giving this whole experience structure, and that kept me from having a personality meltdown or something. I knew that even when the work felt confusing or challenging, it all had a kind of practical purpose. That made it all more manageable in a way.

Courtesy of the artist, Heidi Kirkpatrick, and Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami

The chapter “Sympathy for the Necromancer,” where you discuss extreme cemetery magic, has a different tone than the rest of the book. It’s very intense, very real, and grotesque in some ways. Did you have any problems finding a place to put it in the book? Or did you feel that this section would stand out no matter where it went?

At some point I realized that I had to go somewhere quite dark in order to sort out our collective fantasies and nightmares about witchcraft and magic. “Sympathy for the Necromancer” is really where I go to that place. It was necessary because there is a specter of black magic in witchcraft that raises some ethical questions. That chapter for me is a chance to address the question of black magic but also what I call “occult extremism.” It’s going to spark some conversation.

In an interview you did with our editor, Eliza Borné, you say that “Sky Burial” was the kind of story that changes you in the reporting of it. How do you think you were changed in the process of writing this book?

Well, things go a lot deeper than I would have anticipated and you get a sense of that in the final chapters. I’d like readers to experience that for themselves.

In a broader sense, I spent a number of years meeting with people who were the high priestesses of such-and-such coven, or very respected occultists leading rituals out in the desert. The people who do all of these exotic-seeming spiritual practices and have positions of authority in underground communities work the cash register at Trader Joe’s. Or they have a government job or are the single mom of two kids in a very pleasant Massachusetts suburb. All in all, this project really made this country a lot more fascinating to me. In your day-to-day lives you get used to walking around and making very quick judgments of what people are like, just as a way of understanding your environment. What I learned is that so often people whose lives can seem relatively mundane have this secret other life that you have no way of knowing about and that they don’t necessarily have any plans of giving you access to. And that showed me that people who were maybe frustrated by certain aspects of their lives had still been able to find a way to create another identity for themselves that was connected to something much bigger. Now when I look at the average American, I don’t even know what that term means anymore.

Courtesy of the artist, Heidi Kirkpatrick, and Dina Mitrani Gallery, Miami