Space, Race, and Country Music

Darius Rucker and Tanner Adell at the Windy City Smokeout

By Francesca T. Royster

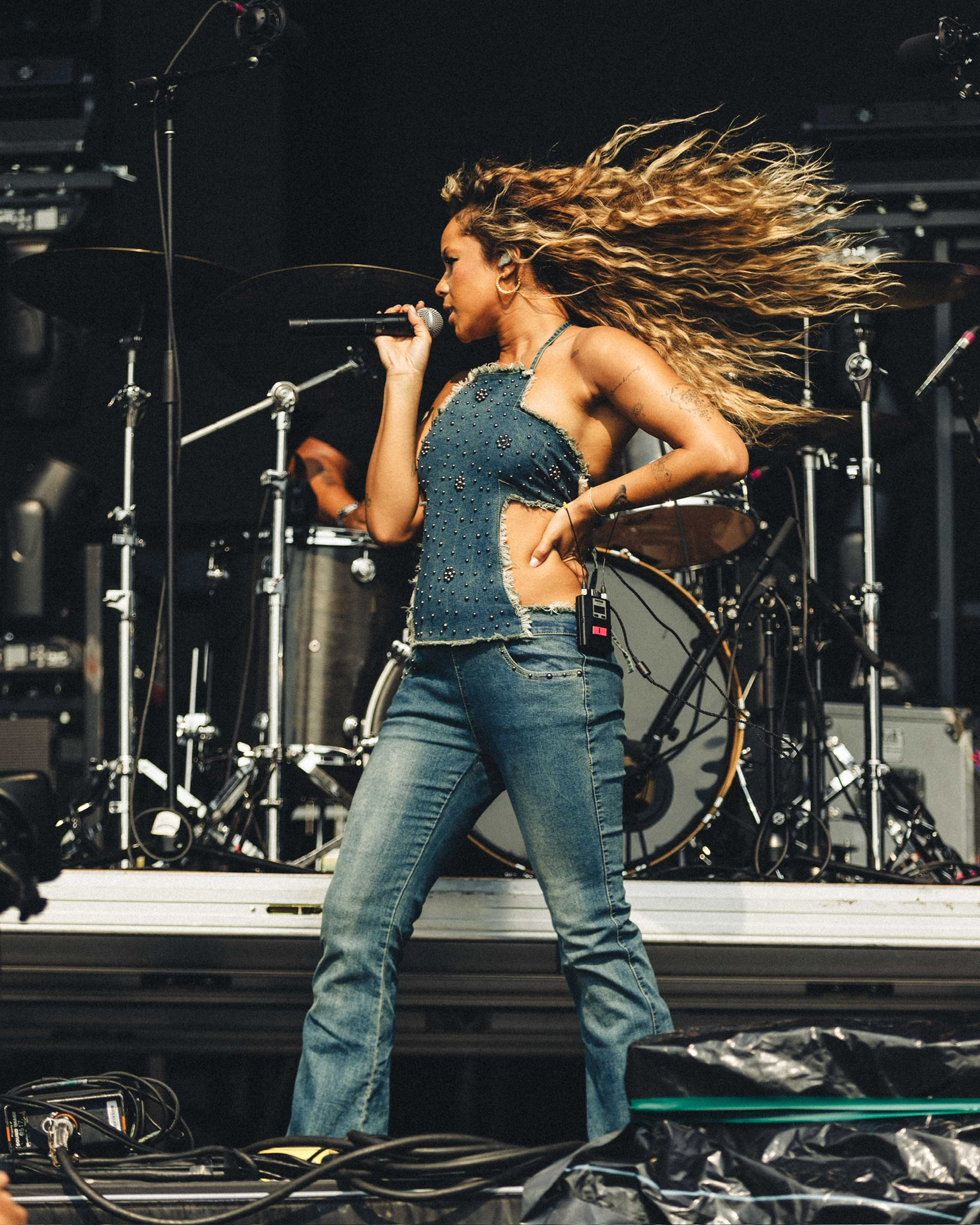

Tanner Adell performs at the 2023 Windy City Smokeout. Photo by Katie Kauss. Courtesy Windy City Smokeout

The 2023 Windy City Smokeout was housed in the parking lot of the United Center, on Chicago’s Near West Side. It’s a massive stadium space built in 1994, an “urban renewal” project that has yet to see full gains for those who lived in the community. It’s best known as the home of the Chicago Bulls, but this summer will have seen concerts from Chance the Rapper, Earth, Wind & Fire, and Arctic Monkeys. I previously attended Stevie Wonder’s “Songs in the Key of Life” tour there, where Stevie was able to create a sense of intimacy despite the 23,000 people in attendance, leading us in a collective “Isn’t She Lovely” that still gives me chills to remember, the song and the space very much alive. But for many activists, the stadium has been a community death knell, a sign that Chicago is becoming too expensive for its poorest residents, especially residents of color.

As my partner Annie and I made our way from one of the stadium’s many nearby parking lots toward the Smokeout—a country music, craft beer, and BBQ fest celebrating its tenth anniversary this year—there was the eerie feeling of walking through a neighborhood that’s been gutted. I could hear cars and the occasional truck from the nearby Eisenhower Expressway, which, after it was constructed in the mid-twentieth century, became an important route from Chicago’s downtown to the suburbs, enabling white flight. I could see new-looking storage units and office buildings, but few homes, restaurants, or grocery stores. Police cars blocked traffic to allow the festival attendees, many of whom were wearing cowboy boots, to walk freely through the streets. The t-shirts we saw claimed their loyalties: Taylor Swift, Jim Beam, Coors, We are Penn State, Breland, New York Yankees, The Chicago Police, And Brisket For All. We saw snakeskin, leopard skin, florals, gingham, and so many cowboy hats, of course—in blue and black and brown and Barbie pink, and one with a wedding veil attached. The crowd moved in pairs and small groups, melding as they approached the entrance like iron fillings drawn by a magnet. As we got closer, we could feel the vibrations from music on the bottoms of our feet.

This was a young, mostly white crowd, and we stood out: a middle-aged Black and white lesbian couple in sensible sandals. But we did see a sprinkling of other Black, Latinx, and Asian folks—it seemed like more than when I had attended the festival in previous years. When we passed one of the last public housing units left standing in the neighborhood, a group of Black teenagers were making snow cones to sell to the crowd. A young Black woman in short locks zipped past us in the opposite direction, maneuvering a Lime electric scooter against the force of the crowd. “Excuse me!” she said, bright and determined, her destination elsewhere.

We came to the Windy City Smokeout specifically to see the Black country artists Darius Rucker and Tanner Adell, a pair of musicians at very different points in their careers. Rucker is at work on his eighth studio album and has had nine number one singles on the Country Airplay chart. He is probably one of the most visible Black country music artists who enjoy mainstream radio play today, a very small group that also includes Rissi Palmer, Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, and Jimmie Allen. Tanner Adell, on the other hand, is an up-and-comer with a growing presence in the Nashville club scene, on streaming platforms, and on social media. Her song “Honky Tonk Heartbreak” soundtracked a 2022 performance by the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, and she recorded a duet called “Cheddar Biscuits” with the Louisiana-born country and hip-hop genre-crosser Willie Jones. At the time of this writing, her growing fan base includes over 450,000 followers on TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter; if she isn’t yet a household name, that should soon change. She is signed to Columbia Records, and her eight-track debut mixtape was released on July 21, 2023.

In a review for Billboard, Jessica Nicholson described the tape’s title track, “Buckle Bunny,” as a song “vibrating with confidence,” praising Adell’s blending of country iconography and hip-hop swagger. The feisty, boot-stomping “Throw It Back” offers an unapologetically sex-positive message about love and relationships; “Just ’cause he’s got them big brown eyes / Don’t mean that he can see,” Adell advises her listeners. Her slower songs cut through the sugar offered by some country ballads to present a saltier, down-to-earth vision of romance. On “Love You a Little Bit”—her most popular song on Spotify, with more than twenty-eight million streams—she offers a moment of quiet, as she realizes she’s falling in love on an everyday Tuesday car ride: “Wasn’t nothin’ special, just the same old same / No love songs on the radio playin’ / You were just drivin’ and holding my hand.”

The fact that the festival featured both Adell and Rucker may be a sign of a changing country scene, where musicians, journalists, scholars, and activists are pushing the industry to be accountable for its exclusionary history. Like other country music spaces, the Windy City Smokeout has undoubtedly been shaped by the segregated history of how the genre has been created and marketed, with its bifurcation of “Hillbilly music” (which later became country music) marketed to white audiences and “race music” (which included blues, rhythm and blues, and jazz) marketed to Black listeners. And of course, Chicago’s country music spaces are shaped by the continued class and racial segregation here, where this “city of neighborhoods” has boundaries that are sometimes unspoken, and sometimes violently felt when you wander into a community that is not your own.

To test the comfort level and feeling of community among Black and other people of color at the festival, I decided on the not very scientific strategy of “the nod,” or what Black poet and essayist Ross Gay calls “negreeting”—a nonverbal form of acknowledgement and connection between Black people in public spaces, however brief. But I was having trouble getting a response to my negreetings. Maybe I was being a little needy, a little too hungry for a response from these strangers. Or maybe the other people of color at the festival didn’t want to acknowledge our shared state of outsiderhood, especially as they kicked back with their white friends and loved ones. Or maybe “negreeting” is just too old-fashioned, a form of connection from an earlier era when our precarity in white spaces was forced to be expressed in code. After about six tries, I finally got a nod from a young Black man in locks, full beard, and a Chance the Rapper t-shirt. He smiled widely at me, and even removed his sunglasses. Time slowed, and for a moment, I felt a little more at home.

“Country” in Chicago, a city with its own complex layers of cultural history, has been shaped by many things: Black and white Southern migrations, each bringing their own country sounds; Latinx communities with their strong links to country music through rancheros and cowboy culture; white flight to the suburbs and subsequent waves of gentrification with the return of young, white professionals. In his new book Country and Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival, journalist Mark Guarino writes that Chicago has had a strong if underacknowledged country music culture; the city was home to the National Barn Dance radio program and to country-friendly labels like Mercury Records in the earlier part of the twentieth century, as well as to Bloodshot Records, home of alt-country in the 1990s. At one time, honky-tonks stretched from Southside to Northside. One of those bars, Carol’s Pub, still remains in Uptown, the Chicago neighborhood once coined condescendingly by journalists as “Hillbilly Heaven” because of its growing white Appalachian community in the 1960s and ’70s.

There are other places for country enthusiasts, too. Latinx country fans can go to Alcala’s on Chicago Avenue, a Mexican family business that features cowboy boots and other Western wear for men and women; and to live entertainment spaces like the historic Latinx drag club La Cueva in Chicago’s predominantly Mexican Little Village, which hosts frequent Cowboy Nights; and Los Globos, also in Little Village, where you can hear and dance to rancheras, mariachi, and Duranguense country music. With line dancing two nights a week, Charlie’s—a gay dance club in Chicago’s Boystown neighborhood—is where white, Black, Asian, and Latinx folks across the LGBTQIA+ spectrum get together to enjoy country music. Chicago-area venues like SPACE and the Old Town School of Folk Music have featured Black country artists like Valerie June, Adia Victoria, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, and the Black Opry Revue, though from my experience the audiences tend to be predominantly white. And in Chicago’s many blues bars, you can hear the sounds of country and blues meeting: the twang of Koko Taylor’s “Wang Dang Doodle,” or the gravelly voice of Stetson-wearing West Side bluester Tail Dragger Jones, a sonic successor to Willie Dixon. But we’ve been conditioned to think of the blues as a separate musical world from country.

Darius Rucker performs at the 2023 Windy City Smokeout. Courtesy Windy City Smokeout

Annie and I had been watching the clouds as we sampled West Side pitmaster Dominique Leach’s delicious Wagyu sausages—her zesty take on the classic Chicago hotdog—when we heard over the loudspeakers that Darius Rucker’s concert would begin a half hour earlier than planned, for fear of impending storms. Earlier that week, the Chicago area had seen seven tornados touch down, including some right in the city. As soon as Darius walked confidently on stage—Ramones t-shirt and jeans, his characteristic graying goatee—the audience roared their approval. A group of white teenage boys began to squeal: “It’s Darius! He’s here! He’s up there!” They were laughing, holding one another’s shoulders and jumping up for a better look. Their giddiness seemed genuine, swept up in the power of watching a veteran of the scene who, perhaps, writes songs that their parents listen to on long road trips.

Darius Rucker is a master at choreographing his audience’s mood, bringing the energy up, then making things quiet, then up again. He is a genuinely inspired performer in this way, unafraid to bring not only muscle and sweat but also well-timed vulnerability, a crack in the mask. He opened with a few of his most upbeat country tracks: “This,” a song about love finally gone right, and the stubbornly optimistic pandemic hit “Beers and Sunshine,” both perfect mood-setting choices for an early-evening craft beer and BBQ crowd. When he segued to a cover of John Mellencamp’s “Pink Houses”—“Ain’t that America for you and me? … Ain’t that America, home of the free?”—the audience was in his pocket. In this crowd, the song felt more like an anthem and less like the wistful reflection on the slipperiness of the American Dream that Mellencamp gestures toward in his opening lines:

There's a black man with a black cat

Livin' in a black neighborhood

He's got an interstate runnin' through his front yard

You know he thinks he's got it so good.

While “Pink Houses” might be about Mellencamp’s hometown of Bloomington, Indiana, it could just as well be about the very neighborhood in which the Windy City Smokeout was taking place. Still, the Chicago audience seemed focused on the chorus, that message of belonging, which they sang along to exuberantly. And what better figure to reinforce a sense of the rightness of the world, in a time of doubt and loss, than a Black country artist who has enjoyed great success in a genre that continues to be contentious concerning diversity and inclusion? (As I write this, the coincidence is not lost on me that the very same day that Rucker performed at the Windy City Smokeout, Jason Aldean released the controversial music video for “Try That in a Small Town.”) Later, Darius brought out his acoustic guitar for a soulful rendition of the Hootie and the Blowfish tune, “Let Her Cry,” a song that Rucker co-wrote. Darius was professorial, intense eyes focused on the crowd as he reached those high notes: “And just let her cry if the tears fall down like rain / Let her sing if it eases all her pain.” A white man next to me, salt-and-pepper-haired with a Kenny Rogers beard, held his lady in his arms in front of him, and they both swayed to the beat. On the periphery of my vision, a possibly tipsy young couple danced a little more raucously and accidentally knocked the cowboy hat off their older neighbor’s head. The pair apologized while crookedly replacing the hat, and all was well.

But then it was time for fun. Darius and his band turned up the funk with three back-to-back ’90s r&b hits currently in high rotation on TikTok: TLC’s “Waterfalls,” Bell Biv Devoe’s “Poison,” and Blackstreet’s “No Diggity,” giving us his bopping double-finger snap and deep knee bounce, bringing younger and older generations in the crowd together. These songs gave Rucker and his band a chance to jam a little, to highlight the skills of his lead guitarist Anthony "Quinton" Gibson and bassist John Mason. The inclusion of these throwbacks might also have been a flex to remind us of Rucker’s own stylistic versatility, even though the rules about “crossover” are sometimes applied unequally to Black artists in country music. (Rucker recorded the r&b album Back to Then in 2002, six years before his shift to country music.) That said, Rucker is at a point in his career where he can experiment with genre. Just a month before the Smokeout, in June 2023, collaborating with the supergroup Dukes of Roots, Rucker released “John Punch,” a reggae track about an enslaved Black man and his efforts to escape—the only song of his career that explicitly names racism and the continued legacy of slavery in the United States:

Think of this injustice

To the human race

Restitution

Remembrance and recovery

Must take place now.

In my time following his country career, it has seemed that Rucker has rarely discussed race and racism publicly. He has taken that risk by speaking about the murder of George Floyd on Instagram and elsewhere, and has received some pushback from his fans. In the sometimes-constraining world of country music for Black artists, “John Punch” is a phenomenal move. Rucker’s title of his summer tour is “Starting Fires,” and while it is likely an allusion to his 2023 single “Fires Don’t Start Themselves,” a lyrically playful song about romance, I hope that “John Punch” is a sign that Rucker might be willing to start a few fires with more public critiques of racism in the future.

Despite the heat of Rucker’s performance, Annie and I felt the temperature shift, and in fear of storms, we moved out of the crowd and over to the Jumbotron closest to the exit. Darius was wrapping up with his final songs: “Valerie,” “Hands on Me,” and, of course, “Wagon Wheel.” Other cautious concertgoers joined us, including an older couple sitting on the curb to rest tired feet. The man wore a battered straw cowboy hat; the woman, a cotton blouse embroidered with flowers. They offered us a negreeting of their own.

Early the next day, I returned to the Windy City Smokeout alone to watch Tanner Adell perform. Adell was adopted by a white family as an infant, together with three brothers, and raised in the rural communities of Manhattan Beach, California and Star Valley, Wyoming in the Church of Latter-day Saints. While she has spoken about feeling isolated as one of the few people of color in these small towns and in her church, she speaks positively about her parents and her “country” upbringing. She has not been shy about discussing the politics of her identity as a Black woman in country. She hails herself as “Beyoncé with a Lasso,” (though the Texas-born Knowles might know how to twirl a lasso, too). Adell has some of Beyonce’s confidence, as well as her golden-brown mane and skin, and the promise of her vocal range and charisma. (The press has also compared her to a young Carrie Underwood and to Taylor Swift.) She plays the guitar and the banjo and the piano, and writes her own songs—sometimes alone, and sometimes with the top country songwriters on Music Row.

Before the Smokeout, I had heard Adell’s song “See You in Church,” a track that calls out religious hypocrisy around sex, on Rissi Palmer’s Color Me Country podcast, and I had appreciated its arch humor. When I learned that she would be at the festival, I did a deep dive into her social media, taking in the enthusiasm of her fans, which manifests in dance routines set to her songs and other forms of praise, with many expressing excitement at discovering a new Black country artist. “The Yee Haw Agenda is in full effect,” one commentor said, referring to the fan-led movement on social media to give more visibility to Black country music and fashion.

As I waited for the show to start, I noticed that the crowd was younger, browner, and queerer than the previous day. A friend group of Black women pushed through the crowd to find a spot close to the stage. The negreetings were flying whenever I looked up from my phone, where I was taking my notes as inconspicuously as I could. An Asian man gave hoots of enthusiasm, pumping his fist whenever the background music paused, encouraging the show to start. A young white woman sipped from her cannabis drink. We were all ready to make some noise. When Adell appeared, she was dressed in diva good taste: a rhinestone-studded denim jumpsuit, with a halter top and flares. White snakeskin boots lent her height. The only other performer on stage was her drummer, Terrence Dre Elam, who is also Black; he was in charge of the drum kit, as well as the beats and synths that would accompany Adell’s banjo, guitar, and vocals.

Adell launched into her set with “Tan Lines,” a hot and heavy salute to farmers, construction workers, and other outdoorsy working men. A white woman behind me sang along, yelling out the punchlines. Later, the same woman said to her companion, “She is just gorgeous! Like Shakira!” I admit I found the fan’s focus on her appearance—and imprecise racial description—a little annoying, but maybe she’s just giving back the same love of the human body that Adell’s own songs promote. Adell gave just the right amount of teasing, making gentle fun of the Lone Star State after singing her love song, “I Hate Texas.” (“Is anyone here from Texas? Texas is very polarizing, ya’ll,” she joked, perhaps mindful of the Chick’s own controversial “I hate Texas” moment.) She made the crowd give their best yeehaws and pig calls. “Ya’ll sound like you’ve never actually called a pig before,” she teased, claiming her own country-girl authority. The crowd cheered with approval when Adell strapped on a banjo for “See You in Church.”

She also performed “Buckle Bunny,” which would be released as a single six days after this performance. While “buckle bunnies”—a slang for a loose woman or a gold digger who hangs out at rodeos to ostensibly collect cowboys’ prize buckles—have been the target of songs by white country acts like Roosevelt Road and Jesse Woods, Adell adopts the identity to exorcise it of its shame (“We all have tramp stamps,” she sings.) In addition to its reclaiming of sex and working-class identity, the song also includes a reclamation of her own Black body and style:

Bottle bleach blond, but I’m no dummy

Big back porch but a little tummy (yeah)

Can’t take nothing from me

I’m a buckle bunny.

I got the chance to chat with Adell after the performance that afternoon. Despite the muggy weather, her trailer was cool and comfortable, and the twenty-seven-year-old looked refreshed, even though she’d just given a high-energy performance less than an hour before. She was gracious and down to earth, helping me to set up my phone to record our conversation. Several stacks of Garrett’s caramel corn were arranged on a side table.

On her Instagram and TikTok accounts, Adell has written about her quest to inject country music with “BGM,” or Black Girl Magic. And her fans seem ready for it. One Black woman posted on TikTok: “We are not giving Jason Aldean any more attention. Go check out Tanner Adell. Her album is nothing but bangers. In a world full of Jasons be a Tanner.”

For Adell, having a Black listenership is important to her vision of success. “I think young Black women especially are ready to have their own culture and community in the country space, just like Beyoncé has created for them in [the] hip-hop and pop space,” she told me. “I think young Black women are ready for that. And Black men. And gays, too.”

I think about what it might take to create a mainstream country music space where LGBTQIA+, Black, and other fans of color would truly feel at home. Adell is helping by offering up wider definitions of what a country girl or boy can be through thoughtful lyrics, embodied performances, and the nods of recognition that she shares on social media. Thinking about the hard work and stamina that Darius Rucker’s career exemplifies, I recognize that artists who challenge the old codes of belonging in country music need and deserve strong backing from the music industry. Digging deeper, we all have to think hard about how segregation still shapes us, determining where we can live, and who and what we think we can love. Performing music that entertains, surprises, and lifts us up—in the face of the history of exclusion that still haunts country music—takes creativity, sweat, and nerve. It also takes a community willing to come together, and to be changed.

In the trailer, I asked Adell how it felt for her to be a Black performer in this still very white space.

“You know, I think I’ve learned I can only do my very best,” she told me. “Other people are going to form their own opinions and there’s really nothing I can do about that. But I know that I did my absolute best, and whatever they think is what they’re going to think. But at night I go home and I think, I put on a damn good show.”