Exiting / In

By Francesca T. Royster

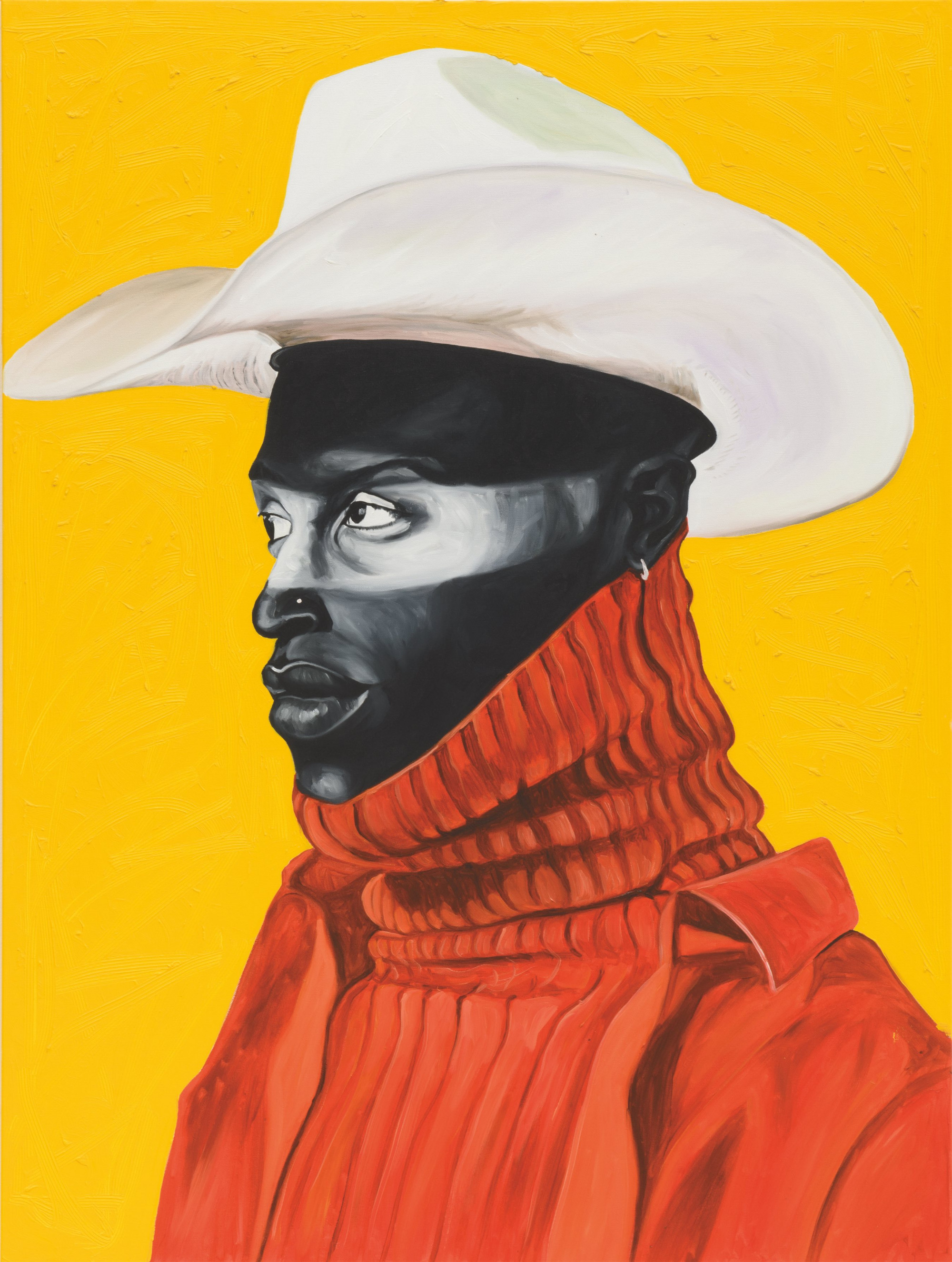

Side Profile of David Theodore, 2019, oil on canvas by Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Artwork photographed by Alan Shaffer

For four years in the Seventies, my father moonlighted as a session musician and live performer in Nashville, while also teaching English classes at Fisk University. He was a conga player trained on the beaches of Chicago’s Lake Michigan, but arrived in Nashville in 1970 as a newly minted professor, the first in his family to finish college. My mother, my sister, and I moved with him. A few nights a week, he and his band would play psychedelic jazz at Exit/In and other spots, or on recordings of country and folk albums by artists who heard him in local clubs. What he found in Nashville was a meeting of desires: a city with a music industry that was booming and almost all-consuming; a Black community that had become fragmented and somewhat wrecked, but was still producing great music; and within himself, a desire for joy in the face of an eight-year marriage that was in trouble.

Our move to Nashville was less a migration than a return, with a difference. My parents were second-generation Chicagoans. Most of my great-grandparents moved from Mississippi and Louisiana and Texas in the 1910s and 1920s. (But in the complexity of many people’s family histories, not everyone migrated from the South. My great-grandmother Pauline, a Polish immigrant, met and married my African American great-grandfather in Cleveland and then made a home in Chicago in 1919.) No one had ever moved back to the South. While Nashville wasn’t where the family came from, it may have represented the South that they broke from. But the struggles of the South had their own Northern version. My grandfather on my father’s side had served in the South Pacific in World War II with the U.S. Marines, and when he came home to Chicago in 1945, he worked several jobs, often at the same time, including foundry laborer, insurance agent, post office clerk, janitor, and drugstore delivery person, all to support his family of eight children on Chicago’s West Side. My mother’s grandmother, who raised her on the South Side in the 1940s, had been a little more prosperous, once owning a building kept afloat with boarders, but over the years she had to constantly fight to keep ownership of it from the bank. Like many of the other women in my family, another great-grandmother worked as a domestic for white people, in this case a wealthy lawyer and his family in Wilmette, Illinois. When my parents met at University of Illinois at Navy Pier, both were struggling to pay for school. They were both in a university African dance troupe, my mother a dancer and my father a drummer. They discovered that they shared a desire to get out and make something new.

When the job offer came from Fisk, my parents responded to a return to the South differently. For my father, Fisk glimmered with possibility, as a place to launch his career as a professor of African American literature at the school where W. E. B. Du Bois taught and the Fisk Jubilee Singers brought Black spirituals to the world. But my mother didn’t want to leave Chicago, or her mother and grandmother, who were deeply involved in our lives, providing daily childcare and emotional support. My father left without us for a few weeks, and they had the chance to imagine a life apart. Reluctantly, my mother decided to move with him. But their reconciliation proved fragile.

When we arrived in Nashville in 1970 when I was three, the city was in the midst of great change, for better or for worse, especially for the Black community. It might have felt a little like walking into a barfight that had ended just moments before: chairs in disarray, glasses broken, people bleeding, a door left open. And a fight could erupt again at any moment. In spring of 1960, the leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Fisk students John Lewis and Diane Nash (who had also come to Nashville from Chicago), launched a powerful campaign to desegregate Nashville’s public facilities. Fisk had been the site of powerful protests, including a 1967 uprising led by students from that university as well as Tennessee State, just over a mile from Jefferson Street, a street which was at the time plagued by bankruptcies, closures, and neglect. Before that, Jefferson Street had been Nashville’s vibrant Black musical and commercial center, home to nightclubs that were part of an important r&b scene, featuring, among others, Etta James and Jimi Hendrix as key performers.

Starting in the 1950s, Jefferson Street had been targeted by the city for “urban renewal,” and fractured by the building of I-40, against the wishes of the community’s leaders. By the early Seventies, approximately six hundred twenty homes and twenty-seven apartment buildings had been demolished. The presence of I-40 also geographically isolated Fisk from Tennessee State and other entities in the Black community of North Nashville. Journalist Steven Hale describes the ongoing trauma of the destruction of this community as “root shock,” borrowing a term from Mindy Fullilove, a professor of urban policy and health, to describe the effects on people who have experienced mass displacement events.

At the same time, two and a half miles away, Music Row was exploding. According to journalist Paul Hemphill, by 1970, Music Row boasted the second-largest recording industry in the country, second only to New York City. It included forty studios, fifty-three record labels, and four hundred music talent agencies. Taking over what Hemphill acknowledges as “a vast Negro section” of the city, the presence of the music industry raised property values, pushing out Black homes and businesses. He writes, “When the city announced elaborate plans some five years ago for Music City Boulevard, land values on Music Row boomed overnight. One corner lot on Seventeenth sold for $39,000 in January of 1965 and the buyer turned down $160,000 for it the following January. A 50-foot lot could be laid for $15,000 in ’61 but was priced at $80,000 five years later.” As Nashville journalist Jewly Hight notes, at the same time that I-40 was being built, “bisecting and decimating neighborhoods and the live music scene along the Jefferson Street corridor, the city was giving institutional heft/legitimacy/respectability to Music Row, perhaps most notably by erecting the original Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum there in 1967. The interstate construction was also completed that decade.”

We lived in Fisk faculty housing, a set of red brick townhouse apartments built in 1968, in the neighborhood that had been siphoned off the rest of the city by I-40. A gleaming metal gate surrounded the apartments. The gate was open during the day, but locked in the wee hours of the morning by a metal padlock and long, rusted chain. In other ways too this was a space of protection: speed bumps to protect the children playing on the sidewalks and sometimes playing kickball in the streets; gravel that slowed the cars down, too, and that we would pick up and put in our pockets for treasure, or break open with hammers to look for crystals, sometimes splinters of rocks sparking up to sting our cheeks, but miraculously never hurting our eyes. We’d play parachute, jumping from the garbage cans while holding plastic bags to catch us, or freeze-tag on the grassy quad in a space adjoining the buildings where you could look into the patios of your neighbors, or hide-and-seek in the sheds that hid each unit’s air conditioners. Sometimes we would scale the walls that protected the power generator at the center of the complex, sneaking to play doctor in the midst of its ongoing electric buzz, out of parents’ sight and hearing. We were kids of the faculty and staff and Fisk, mostly Black and Brown and occasionally white, and while our parents felt like it was safe enough for us to play outside without a parent watching over us, I was always aware of that gate, and the implied separation from the neighborhood outside of it.

My parents’ marriage was only eight years old when we came to Nashville, and already it seemed to have withered on the vine, a mixture of small betrayals, layered upon one another; the violence of their families of origin, yet unprocessed by therapy; and their youth and inexperience. They married when both of my parents were still nineteen, and according to the sexist rules of the State of Illinois, my mother was considered of age, while my father was not. My grandmother had to sign for him. They were parents almost right away, my sister born just six months after their wedding, and then me, four years later. And while both were committed parents, they were also stretched thin. When we got to Nashville, my father had finished his doctoral coursework at Loyola University, but not his dissertation on the poetry of Langston Hughes. So one of his responsibilities (along with teaching at Fisk and sometimes Belmont College, and also pursuing drumming) was writing his dissertation. My mother stayed home with us for those first years, and then started working at a drop-in community center, sponsored by the Nashville Public Library, called Read and Rap. It was located in the James A. Cayce homes, Nashville’s largest and oldest public housing developments.

I sensed my father’s need for escape when I was a child, even though I couldn’t put it into words. Unless he was listening to his music, his energy was often frenetic, sometimes focusing on small problems around the house. (It was later, in watching Warren Beatty’s 1991 performance of mobster/entrepreneur Bugsy Siegel, that I recognized in my father this man bursting with energy, and who could not sit still. He shared with me as an adult that this frenetic-ness came out of his grief about a homelife where he felt he had no intimacy or authority.) My parents would create failed campaigns to connect: the waterbed purchased together at 100 Oaks Mall that sprung several leaks; the tandem bike that was bought for riding dates at Centennial Park but was mostly used by my dad to take my sister and me around the neighborhood. Both of my parents wrote, and they performed their poetry together. Sometimes those events were fraught with small dramas. They never hit each other, but they bickered, or just ignored each other, building their own worlds. My mother seemed happiest at her job at Read and Rap or when it was just the three of us, my sister and me accompanying her on a shopping trip or making dinner. When I got to sit in on one of my father’s classes, or to watch when he recorded at a studio, I saw another side of him, too: relaxed, engaged, and focused. I could see it on his face as he played his drums in the park, his eyes closed, face raised to the sun.

I recently joined my father via Zoom, to ask him about this time and how he got involved in the Nashville music scene. We were already used to this way to connect and share difficult stories in these years of the COVID-19 pandemic, both of us in our office sanctuaries surrounded by the familiar comfort of our books. Lit by the warmth of his desk lamp, my father’s face was open, eyes magnified by his reading glasses. His voice was halting at first:

It’s a little painful how I got involved but it’s real. I was very unhappy and I decided, well, that I was going to have to do something else in my life besides my teaching career because my nights, after I got done with my teaching—which I loved—there wasn’t much that was exciting for me, or pleasing. I needed some zest and creativity in my life. So I decided to put my drums on my back and go out and play, and I went and found a club called the Black Diamond on Jefferson Street. Most of the guys I played with were from Tennessee State or had graduated from Tennessee State, and I got into playing rhythm and blues, especially Southern style. And from there, things kind of exploded.

At the Black Diamond, my father was reintroduced to the r&b that he had grown distanced from as a graduate student and young father with no time to go out at night. He’d watch men and women dancing and relaxing and finding their joy to Wilson Pickett and Sam and Dave. He began a routine of playing at different clubs, moving from Black clubs like the Black Diamond to predominantly white spaces like Exit/In, where he and his band, the John Betsch Society, would play free jazz and meet members of the alternative music community, including young multi-genre artists Dianne Davidson, John Hiatt, Jimmy Buffett, and Mac Gayden. Dad tells me he felt from these musicians in the space of Exit/In a genuine desire for connecting and for pushing the boundaries of country music and other genres:

One of the things that started to happen was that the white musicians would see me play, and we’d get to know each other, and they started bringing me in. From there I started working at other [white] clubs like Red Dog Saloon and General Store and also the music studios in Nashville, working with various musicians on their albums.

Of course, the hunger for Black musical expertise that my father found coming from white musicians, especially musicians in country music, was not entirely new. Black music has always been foundational to country music, from the country sound of banjos, an African instrument; to the caricatured blackness of minstrel shows and medicine shows; to the apprenticeship of white country performers (like the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers) to Black ones. Country’s history has included a slow but steady stream of Black performers who attempted to break into its segregated world. But as historian Charles Hughes points out, this period from 1970 to 1974 was of particular importance for white country music identity, particularly in what he calls the “Country Soul Triangle,” the three-pronged network of recording studios from Nashville to Memphis to Muscle Shoals, Alabama. While in legendary studios like Stax and FAME, 1960s Black soul artists and white country music artists often used the same songwriters, musicians, and producers, the 1970s saw a kind of white backlash. Even when white country artists demonstrated a respect for Black music, they often left actual Black musicians out of the limelight. In this period, a new generation of white country artists who were interested in integrating soul, r&b, and funk into their music were credited for being experimental and expansive, while Black music was treated as the raw material for white creativity.

The musical scene that my father entered in Nashville was one, then, that was not risk-free for Black musicians. The appetite for Black musical styles was strong, and many white musicians felt free to visit Black musical venues and to invite Black musicians to come and play and record with them. But many Black musicians, especially those raised in the South, did not feel as safe to travel into white spaces. Black Northern transplants like my father, coming into the scene from the outside, may have felt freer to cross these racial lines and collaborate. The mostly white and subcultural Exit/In club was one of those spaces. And it was there that my father built a multiracial network of musicians that he played with. This led to opportunities to also record in the studios:

One of the greatest experiences for me was to go into the studio and work with country and western musicians. I listened to the music a long time before that, because my mother loved it when I was a child, but I didn’t really understand the music. But when you go in to record with musicians, whatever the music they play, you come out understanding it, where it comes from in their hearts. That was really a mind-opening and heart-opening experience, because I was playing with the greatest musicians on the planet, because they were there and that was what Nashville was all about.

My father brought to these new collaborations his own strength and stamina built from playing for hours at live performances. As a teenager, he learned congas at the hands of the drummers who would meet at the beach that spanned South 63rd Street and South 49th Street, at the eastern edges of Chicago’s Hyde Park and Woodlawn neighborhoods. There, every weekend in the summer, the players, mostly men, would drum for hours, polyrhythmic patterns from the African diaspora pounding against the limestone boulders lining the beach. There was fellowship across neighborhoods, sometimes across class, as they taught one another what they had learned from the elders, or from records like Patato & Totico, or artists such as Olatunji or Tito Puente or Mongo Santamaría or Willie Bobo. If you were bold enough to jump in, you were expected to hold up the beat responsibly, keeping time for the dancers, whether you were a drummer or a passerby grabbing a spare cowbell or maraca. This was serious play, a way to manhood distinct from other ways of becoming a man on the South and West Sides, different from sports, or gangs, or doo-wop. Strength was shown through skill in playing and listening, and in endurance, as players might perform as long as six to eight hours at a time.

When Dad was invited to perform as a sideman in the Nashville studios, he met skillful, professional sidemen who would lay down their licks with style and expertise. The culture of playing in studios was quite different from performing at parks and beaches or in clubs. But his endurance was admired by his colleagues. There, despite some of the racial tensions of Music Row, he found respect and passionate focus that brought out his own best work, especially with country folk artist Dianne Davidson. As he describes working with her, his voice grows thoughtful:

Dianne had such a beautiful voice. All I had to do was really listen to her, and much of what I was going to play just happened. When she sang, all you had to do was put your hands over your drums and allow her singing to go through you and you’d know what to play.

One night Davidson invited our whole family to her house for a band practice. I remember riding through the Tennessee hills through the fog to her home, covered with a blanket because it was already past our bedtime. When we got there, we were surprised by the presence of two wildcats—ocelots?—lounging on the velvet Victorian couches, padding their way across the worn oriental rug to us to rub against our legs, the roughness of their tongues as they licked us hello just this side of sharp. I remember my mother tucking me in on one of the couches, my sister and I foot to foot, while Mom perched beside us to read the paperback novel she’d brought with her. My father disappeared with the rest of the band to practice. He was the only Black person in the band, and we were way out in the country. Maybe that’s what made my mother nervous, staying close by us, not getting up to talk to Dianne or the band, or maybe (maybe?) it was the woman at Dianne’s side, rubbing her shoulders. I hope not, but it could be. As I nestled in, comfortable in this new space, something opened in me at the sight of the two women, the way that they seemed both like sisters and lovers. As I fell asleep, I could pick out the sounds of the rest of the band, the bottom beat of my father’s congas, the patterns I always heard at home, traveling across place and time to us in that eccentric farmhouse in the hills, and carrying me into my dreams.

The lyrics for “Delta Dawn” tell the story of a woman who seems stuck in time, and perhaps in her own desires. Once the “prettiest woman you ever laid eyes on,” she’s usually seen wandering the streets of Brownsville, suitcase in her hand, faded rose in her lapel, telling anyone who will listen about the working-class, dark-haired stranger who will take her far away from here, to his “mansion in the sky.” Maybe it’s a song about frustrated sexuality in a society that represses women’s freedom. Maybe it’s a metaphor for the need for a New South, the old one outdated and stuck in old dreams of a plantation past. But in Dianne’s rendering, we are welcomed into Delta Dawn’s yearning. Her line “Did I hear you say / he was meeting you a-here today?” has the tone of an empathetic listener, someone sitting at Delta’s elbow with a cup of coffee and a cigarette. The sense of empathy in this version is made possible in part by the role of the conga playing beneath it. Dad’s conga makes Delta’s yearning something that’s alive and present, with a beating heart, not just a stagnant dream. Dad told me that he was dissatisfied with the engineering of the song, as it was recorded, because you couldn’t hear the full richness, timbres, and textures of his drumming, including the distinctions of a closed versus an open hand slap. But that beat still gives the song presence, energy, and depth. It is the beat of the living underneath the faded rose, the truth within the storytelling, the presence of other bodies who are watching her and bearing witness.

My parents decided to separate in 1974, and while I missed my father, I also felt a great sense of relief, even as we packed up to move out of the only home I had remembered. As a young person, I felt torn during my parents’ fights, unsure of who was right, or where to put my loyalties. In the early years of their divorce, I split myself between identifying with the everyday struggle of my mother, making a new home and life for us, and with my father, who struggled to stay connected to us while also creating a life away from Nashville, in Albany, New York.

Perhaps for a time, my father’s music gigs distracted him from the unresolved conflicts of his marriage, and potential loss of our household. After Nashville, my father never again pursued a recording life. I had always assumed that he had been tempted by the life of being a musician, and that he left it behind because of some of the more sensational aspects of the entertainment industry, like drugs or alcohol. But in our recent conversations, he shared with me that what was dangerous for him about the life performing in clubs and studios was not the drugs or alcohol, or even the late nights or time on the road, but the ways that the music took the place of other joys and achievements that he wanted for himself: to grow as a scholar, to find a true life partner, and to build a better family with his daughters.

After his divorce from my mother, and some therapy, my father uncovered a life script of dying prematurely. In this premonition, he’d die at age thirty-three in a car accident, fatigued after a day of playing his drums, and that this way of dying had felt inevitable since he was a young person. Indeed, a few years into his thirties, before he separated from my mother, he started having a series of car accidents after sessions of playing with his drums. They were minor fender benders at first, and then once, he completely rolled over his turquoise Volvo station wagon with the drums packed inside. This startled him enough to seek help. Eventually, he worked to create a new vision of a long life, still with his music as part of it, teaching and writing about music and playing with African dance troupes in his new home.

A few years after his discovery in therapy, my father almost found himself in another car accident. He had been playing drums in the park with a friend, someone who had formerly been incarcerated in Attica prison. Though they were both exhausted, they got in the car, and my father drove through a red light on a very busy street. When the police stopped him, they sent him home without a ticket, telling him that he was very lucky and that he should have been killed. My father is convinced that it was his own decision to live a long life that protected him. His second career of recording and gigging in Nashville had fed him by connecting him to new people and places, but ultimately, he needed music’s power of self-reflection and transformation to make the life that he yearned for. As he told me at the end of our conversation:

Music has always helped me to live, whether times were good or bad. And the transcendent experiences I learned to achieve first through music have always served me in the most positive and constructive ways. They never distracted me from my need to become a better person and build the life of my dreams. They actually did just the opposite.

In thinking about the continued power of music in his life, my father told me about watching his own father, who played drums and harmonica in Chicago:

My memory of him playing the harmonica is that he would be lying in his bed. His feet would be out and you could see his toes, and he would be playing and his toes would be moving at the same time. That’s the way I remember him. He would never be playing the harmonica standing up. And that was a kind of sanctuary for him.

Before my father left our Nashville home, he created a musical space in our living room: conga drums with special homemade suede covers lined up along the wall; framed photos of jazz greats and African dancers; lovingly assembled stereo equipment, including a reel-to-reel tape recorder, turntable, and speakers; and a long triple-row of LPs. This was where he would play his drums along with music that he’d listen to on his headphones. He had pillows on the floor, and he’d often invite my sister Becky and me to come and sit with him to listen in. This space, wedged between the couch and the dining room, orderly and inviting, felt to me like an entrance into another space, and an unknown time. I never knew what to expect when my dad popped on the headphones for me to listen. It might be one of Alan Lomax’s recordings of field calls or John Coltrane or Miles Davis or Celia Cruz or a little Marvin Gaye. Sometimes he’d be listening to the rehearsals of one of his bands, or sometimes he’d tape new songs from the radio station. Becky and I would bring over our favorite music to play on the stereo: the Jackson 5’s ABC or Peter and the Wolf or The Nutcracker Suite. I felt special when my father invited me to this space to listen, or to get a lesson in polyrhythms, trying to keep time on the cowbell while he played his bongos beside me. No one among my mostly white friends had that kind of relationship with their parents through music. In our home, where the sadness seemed to lurk in the corners, the presence of music—the drums and the magical headphones—were important routes inward and outward. A temporary sanctuary from sadness, and also a means of transformation. An exit in.