Photo by Tatum Shaw

ON BEING A WRITER FROM JACKSON

By Katy Simpson Smith

You could tell by the sound who was getting hit. Fists bounced off the skinny boys with high thwacks; when the bigger ones got beat, the sounds were damp, like someone had gone into the forest and kicked a nurse log. Whoever it was, the violence pulled in a crowd. During these bouts, I’d stand in the halls of my high school, pressed against the lockers, watching the boiling edge of the mob, unable to move away. The cries of Fight! Fight! became just another vocalization of a violent legacy that has somehow defined for me what it means to be from the South, and certainly Mississippi: bodies against bodies, nature crawling into cities, road kill, tornado drills, train tracks that divide white from black. I can’t look away because there is also a vitality in this violence, and the split between the beautiful and the broken is often unclear; because it confuses me, I’m addicted to it. Those boys in the hall pummeled the wits out of each other because one of them grabbed the ass of the other’s girlfriend at a party last night, and one or both of them were in love, and this was worth watching from up against the lockers.

In the middle of downtown Jackson stands a triangle of statues carved in rough-hewn stone, their backs to each other, facing out toward the city: William Faulkner, Richard Wright, Eudora Welty (who is sitting, because she’s a lady). Passers-through might not look twice, but locals know which one of them doesn’t belong. In Faulkner’s place should be Margaret Walker. Wright, Welty, Walker: those are our Jacksonians, the old guard, the outsiders of gender and race and class whose stony shoulders we stand upon. They saw the weirdness and the wrongness and made things of enduring grace. To be a writer in Jackson is to be a witness.

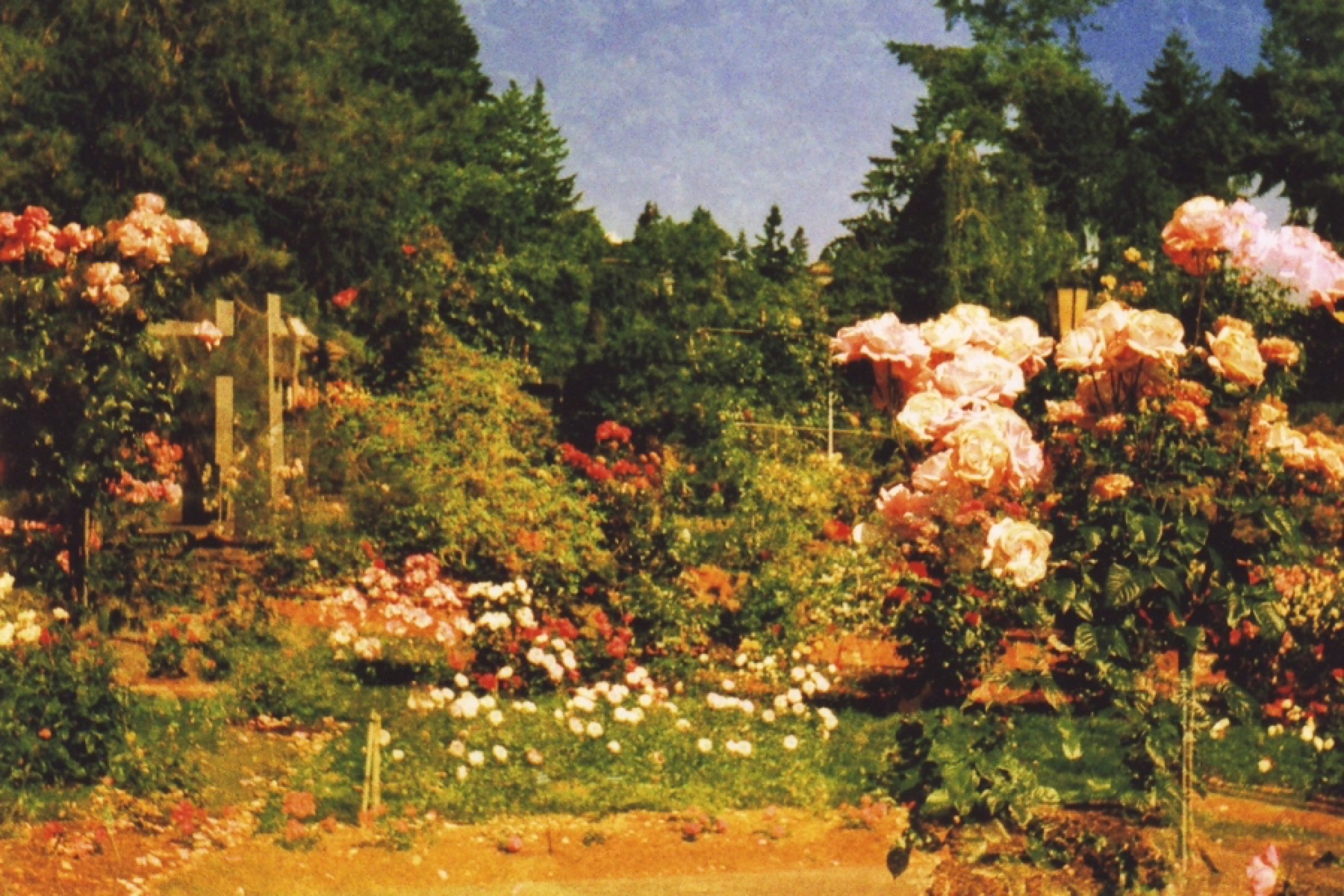

Of all the beautiful things in Jackson—the Pearl River, the state fair, the Jackson State marching band—the nicest is my mother’s garden. If you ask her about it, she’ll say it’s irredeemably disorganized, that weeds fill most of the spaces where flowers should be, and that she’ll never have enough time to fix it up right. But to me, and to the people who walk past (“perfect strangers and imperfect strangers,” in Alice Walker’s words), it’s a glory. A Lady Banks rose strangles the arbor, an ancient vitex explodes in violet fireworks every summer, demure geraniums and dianthus snuggle against wild cardoon and native grasses, and in the center of it all sits a stone-rimmed pond that hosts a circus of dragonflies and, in the hottest months, is nearly choked with fat bubbles of water hyacinth. But my mother’s garden is also where our family quarantines the dead—snapping turtle shells, deer bones, an alligator skull pulled from the Pearl—until the smell has aged away. During Easter egg hunts, we are just as likely to find the bloated carcasses of sex-sated toads. Cats gather there under the old roses to stalk blue jays, anoles, pipevine swallowtails. Rotten vegetables and coffee grounds get thrown onto the compost pile, turned, and folded back into the soil, out of which passionflowers grow. Even the sweetness of the jasmine and tea olive feeds on the dead.

Something in me is tuned to cruelty, to the breakages in the world. Roadside armadillos on their backs, their legs up goofily—this breaks my heart. Don’t get me started on the sight of dead deer, their weight, the fur on their flanks that looks as smooth and blonde as a pit bull’s. It is too easy for me to imagine pain. The first story I wrote (age five? six?) involved ponies attacking each other with chainsaws. One of my first attempts at historical fiction told the tale of a family dog pushing twin girls off a balcony to their death (rather, “-----to their death”; the dashes were important). Their bereaved mother then drowned the dog. I was twelve. This obsession with violence didn’t come out of a vacuum. I understood, even as a child, that my world was built from people hurting each other, built on strange accidents, on family ghosts, and that this ran through the vibrancy of daily living. (My great-uncle, still a boy, did indeed fall to his death from a balcony. I wrote about it because this brutal under-layer seemed to be the soil out of which everything good grew.)

Shortly after my childhood home was built in the 1920s, a teenage Eudora Welty moved into it with her family while their house was being constructed five blocks away. When I was a little girl, she was already elderly, a small woman we’d sometimes see in the Jitney 14 grocery store. I used to imagine she had left something for me in our house, but I never found it. The house itself was built on shifting layers of Yazoo clay, which means certain rooms tend to migrate away from others. One party trick is to place a ball on the floor and watch its wild meanderings. My parents’ bedroom is sinking down to the south, and a crack has formed along the adjoining living room wall large enough to let in a Virginia creeper. Sometimes my parents trim it back. At one point, in the years between the Weltys and the Smiths, the house was occupied by a man who chain-smoked the walls black, who ran a chop shop in the backyard, and who, in his dotage, would wander the neighborhood in a trench coat, reciting “The Waste Land” in exchange for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. He ended up in the state mental institution, from which he once wrote us a letter, asking for a watch.

When I was in middle school I was slapped by a stranger. It happened after the last bell had rung and all of us scrawny, near-pubescent children were flooding down the hall toward the buses, our parents’ idling cars. I was twenty yards from the door when someone walked past me, turned, and whacked me across the face. I’m fairly sure it was a girl, though I can’t be positive. But she was black, because most everybody at my school was, and I was white. Already I knew in some pocket of my Jackson heart that this was simply my due. After all, my mother’s garden blooms not in spite of oppression; my mother is not Alice Walker’s mother. I returned to school the next morning like nothing had happened.

I can’t write a history of Jackson; I only know what I absorbed from the city, which is less fact than emotion. I know that our public library branches are named for Welty and Wright, but also for Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers. See? Even our books are imprinted with a violent past—or rather our activist history is woven proudly into our stories. The writers and the fighters here are kin. I also know that train tracks split the town in two, mostly white from mostly black. In high school, we’d walk those tracks late at night, feeling a heady power, a sense of near-transgression. We ourselves were white and black, and still uncertain about what that meant. We threw rocks; we held hands; we warbled Don McLean’s “American Pie” into the darkness. We thought not about race or history but our own short lives. On either side of us, the city continued to unravel its complications.

I live in New Orleans now, because New Orleans is where I want to live, the city I choose. It’s got shotgun houses and all-the-time music and subtropical plants (the citrus trees and banana plants that jungle our streets would freeze in Jackson, three hours north). But it will never be home. When I tell people about Jackson, I swing between self-deprecation and boosterism. It’s essentially a small town, I say. Growing up, it felt like there was nothing to do. If I catch a hint of snobbery—or pity—in the listener, the pendulum swings back: But it was an incredible place to grow up. People looked out for each other, and we understood complexities of race and history that outsiders never could. Of course, both thoughts are true. My sensibility as a writer is permanently colored by the duality of what Jackson stands for, and it’s no wonder, given its twisted eras and its through-line of struggle, its lushness and its decay. Beneath every rose bush here is a bone. Ultimately, I write because I admire the honest, the dark, and the lovely, because I’ve always been the girl in the corner, wherever I am, observing. To be a witness is a privilege, because what we witness is a community confronting its own injustices. When home is a place where the past is mostly brutal, you learn to step outside the violence and watch it, to weave the beauty in so that your history is bearable. To turn truths into stories.