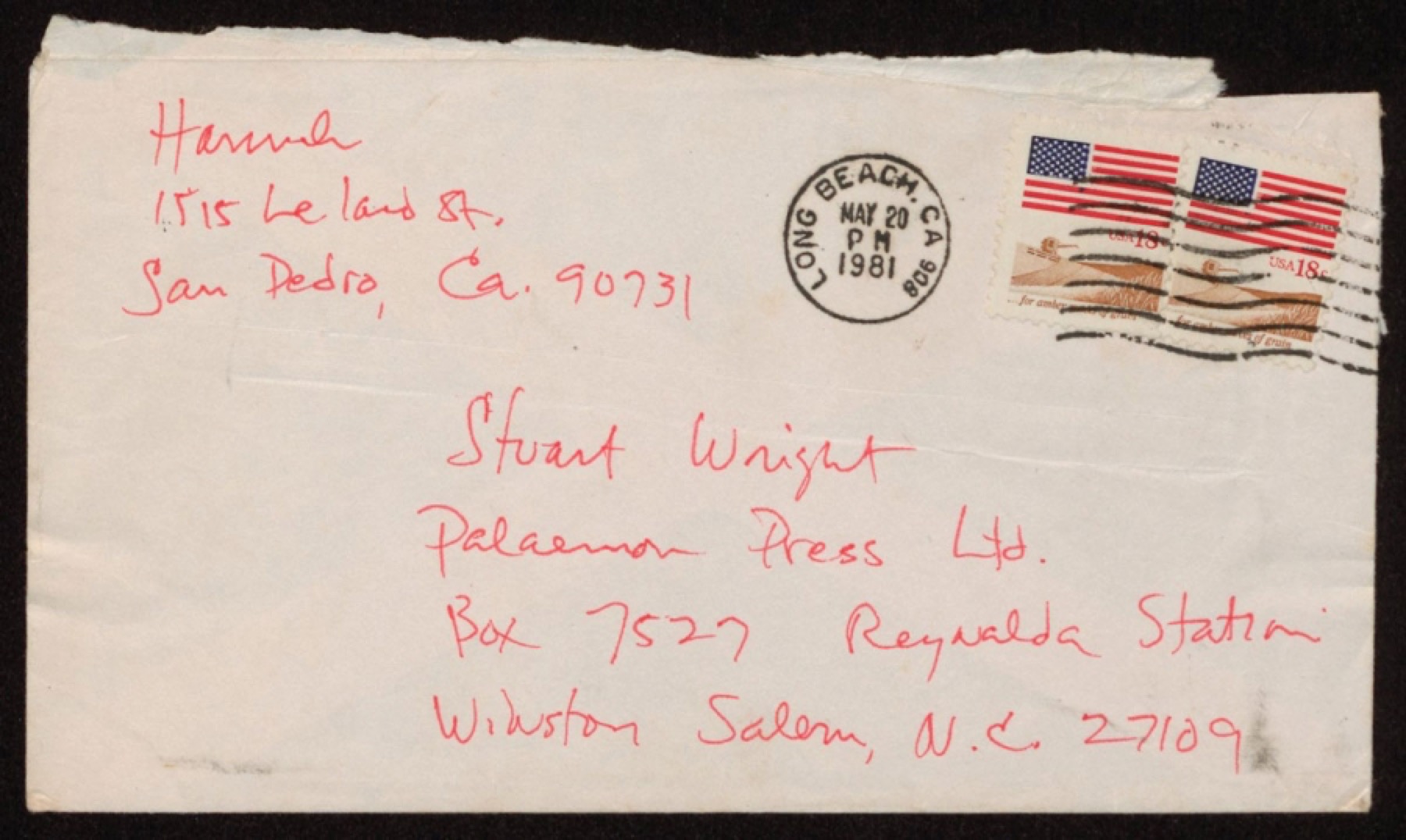

An envelope from Barry Hannah in California. © The Stuart Wright Collection, East Carolina University.

PULL BACK AND RELOAD: BARRY HANNAH IN HOLLYWOOD

By Will Stephenson

Outskirts of the Southern Canon

“Every morning I wake up and I’m at the bottom of a very deep hole,” Robert Altman once confided to the actor Peter Gallagher. Over the course of a few strange decades, Altman had gone from an Air Force pilot and an entrepreneur in the once-promising dog-tattooing industry to one of the world’s most celebrated filmmakers, acclaimed for his frantic, revisionist takes on Hollywood standards—the war epic (MASH), the Western (McCabe & Mrs. Miller), the film noir (The Long Goodbye), the musical (Nashville). Writing in the New Yorker in 1975, Pauline Kael had compared him to James Joyce and deemed him “the most atmospheric of directors.” He was fêted in Berlin, Venice, and Cannes—and in Hollywood, too, for a while. But by 1981, Altman had never been deeper in the hole. It didn’t matter how he scratched and clawed during the day, he told Gallagher; every morning, the hole was there to greet him.

In a word, the problem was Popeye. He’d spent a year on the island of Malta making a live-action adaptation of the classic comic-strip, stranded in the Mediterranean Sea with Robin Williams, Harry Nilsson, Robert Evans, and just enough booze and coke and pot to make the whole experience feel almost normal, which it wasn’t. In the end, they made a masterpiece—dark and mannered and often nearly incomprehensible—but a masterpiece all the same. (It’s enough to say that no other film even resembles it, except possibly something by the Chilean avant-gardist Raúl Ruiz.) But almost no one viewed it that way at the time, not even the participants in its production, who remained vaguely haunted. “Very few people were left sane on that island,” Altman’s son Stephen later remembered. Popeye screenwriter Jules Feiffer has said that Altman “was destined to go into the wilderness” after the experience on Malta. “If anything,” Feiffer said, “he willed himself into the wilderness.” The film made money, but not enough for Altman to regain the good graces of the major studios. While he’d always behaved oddly, the Popeye shoot struck them as frightening. Word had gotten around. “Suddenly, no one answered my phone calls,” Altman told the New York Times in the summer of 1981. “I feel my time has run out.”

Across the country, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, the novelist Barry Hannah was in a wilderness of his own. Like Altman, he’d emerged in the 1970s as a radical new voice. His 1972 debut, Geronimo Rex, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and his books Airships and Ray had seemed to offer a new range of manic possibilities for American fiction—for the English-language sentence, according to some. Richard Ford credited him with creating “a whole new syntax,” and the reviewer for the Times—who called Ray “the funniest, weirdest, soul-happiest work of fiction by a genuinely young American author that I've read in a long while”—argued that to account for Hannah’s unique style would require “new strategies, new arguments, new adjectives, new everything.”

But Hannah was a bad drunk. The kind of drunk forever pursued by rumors and legends of his bleaker exploits—and the kind of drunk about whom the rumors and legends were mostly true. “I lost my second marriage because of drinking, and I loved the woman very much,” Hannah remembered years later. “But I thought I needed booze to write.” Reading Ray, you can almost sympathize with this perspective. Its narrator speaks in tongues, in wild bursts of inane beauty: “My eyes are full of yellow bricks. There are dry tiny horses running in my veins.” This is a voice that appears to owe something to a partial derangement of the senses.

Not long after its publication (in 1980, the same year as Popeye’s release), Altman picked up Ray—likely through the intervention of Lynn Nesbit, Hannah’s agent—and became obsessed with the book. When he first arrived in California after World War II, Altman had considered himself a writer. His archives contain poetry and unfinished stabs at fiction, and over the years he would go on to develop projects, successfully and unsuccessfully, based on work by writers like Raymond Carver and Thomas McGuane. But he happened to encounter Ray at a crucial juncture—his career was in jeopardy. He had been forced to sell his studio, Lion’s Gate, and to retreat from the Hollywood establishment. The idea was to make smaller projects for a while, direct some theater, rediscover himself as an artist. And, no less important, the Writers Guild was embarking on a months-long strike. Altman was in the market for a writer of genius; all the better if he didn’t belong to the union. He asked Hannah out to his home in Malibu, and Hannah agreed. The author had hit a wall in Alabama, and if he was worried he couldn’t write sober, he was equally worried he couldn’t stay alive unless he tried. What better place to dry out, clear his head? No matter that he hated the beach.

There exists at least one person who has worked intimately—and independently—with both Hannah and Altman, and has lived to tell about it: the screenwriter Anne Rapp, who studied under the former at the University of Mississippi and wrote two scripts for the latter in the late 1990s, Cookie’s Fortune and Dr. T & the Women. Rapp, who is now based in Austin, even credits Hannah with indirectly launching her Hollywood career. He so admired a one-page story she read in his workshop that he sent it to his longtime editor Gordon Lish, who published it in his seminal literary magazine The Quarterly. Altman’s editor got a copy and showed it to the director, who soon put Rapp under contract.

When Altman discovered she was a former student of Hannah’s, he began to tell her stories about their attempts at collaboration. Hannah had driven out to Hollywood proudly on his Triumph motorcycle, he and Altman having settled on a meeting place, whereupon Altman was to guide him the rest of the way to his home in Malibu. But when Altman arrived, Hannah hadn’t showed. The filmmaker waited for an hour, increasingly frustrated, until he noticed, across the street, a peep show and adult video store. As Rapp remembers him putting it, Altman thought to himself, “That fucker would be just crazy enough . . .” He wandered inside the adult emporium and there found Hannah, deeply absorbed.

Altman arranged to put Hannah up in his house, right on the beach at Malibu Cove. He installed him in the crow’s nest, with a dramatic view of the ocean. “Most writers would kill to have a place like that, but Barry hated it,” Rapp said. “He turned his desk to face the wall.” Worst of all, she said, were the sounds: the waves and gulls and laughter, the ambience of West Coast leisure. Hannah later got to the root of the problem in a brief sketch in his memoir Boomerang:

When I was working with the kind and brilliant Robert Altman in his wooden mansion by the sea, I was in a tower of Plexiglas with seagulls flying around me and the Pacific rolling under the house like a white man’s dream of peace. I had a typewriter and there was a Spanish maid who would bring me coffee. But it was too nice and I had to turn on the radio. Altman came up and asked me how could I work with the radio on that loud.

He also watched television compulsively, gravitating toward the lowest common denominator. “Benny fucking Hill. Been loving him since lonely days scriptwriting for Altman,” he later wrote to a friend. “Hill was the only thing made me laugh on the box.” Hannah explained that he needed the distractions to “remind me of all the trouble in the world.” It’s also likely that Hannah’s halting attempts at sobriety weren’t conducive to mastering a new craft like screenwriting. As he told one interviewer in 1982, “I went out there to get healthy, physically.” The combined pressures of following up Ray and breaking into Hollywood simultaneously were made more violent and grotesque by the harmony of his surroundings. “I could not accept paradise,” Hannah wrote in Boomerang. “I had to drag in the bad music and the cigarettes. I had to foul up the air and my ears. With no whiskey, what else was there to talk about?”

The main thing the two men talked about was an idea that originated with Altman, about women who worked for the power company in Seattle. He thought Hannah could flesh it out, work his magic, invent a set of characters who resonated. The two men shared certain critical ideas about what was important in art and what wasn’t. “I care nothing for plot at all, that should be obvious,” Hannah said in an interview in 1987. “I think plot is always phony. What I'm interested in is character and language.” Altman, by all accounts, agreed. “Stories don’t interest me,” he explained in 2006. “Basically I’m more interested in behavior.” As one longtime collaborator, the screenwriter Barbara Turner, once put it, “What appealed to Bob was the character. The character is this creature, and I think Bob liked creatures.”

Hannah first mentions the project in a 1981 letter to Lish: “Am writing with Robert Altman, Power and Light, about women hardhat workers. Altman seems to love me.” It quickly became clear, though, that Hannah wouldn’t last at the Altman home. While the director spent most of the day at his editing suite, his wife, Kathryn, and youngest child stayed at the house, and became more and more unnerved by Hannah’s presence. Among other things, Kathryn Altman had heard the rumors about Hannah’s behavior. As Hannah wrote Lish, “Lynn Nesbitt told Altman . . . that I shot at my ex-wife until I was out of bullets, then nailed her with an arrow from [a] bow. See, I’d like for this shit not to go around about me, although Altman didn’t care.” The truth of the story was less horrific, but just barely: After an argument with his wife, Hannah really had shot an arrow into their first-floor window, “in a drunken lonely rage” (though he “knew damn well nobody was near,” he clarified to Lish). But Kathryn wasn’t amused. “She was half-terrified of Barry,” Rapp said. “Scared to death, like ‘Oh my god, there’s a maniac in the attic.’”

The backside of an envelope from Barry Hannah in California. © The Stuart Wright Collection, East Carolina University.

The backside of an envelope from Barry Hannah in California. © The Stuart Wright Collection, East Carolina University.

Hannah relocated to nearby San Pedro, initially—according to one friend—for rehab, then for a small bungalow on Leland Street, his rent paid by Altman, who still hoped to make something of Power and Light. Desperate for income, Hannah was also scheming to put together a new story collection with Lish and reluctantly beginning to agree to temporary teaching gigs around the country. But Power and Light was his priority, and it was around this time that he began to correspond about the project with a small-press publisher in Winston Salem, North Carolina, named Stuart Wright.

The letters are gathered in Wright’s archive at East Carolina University. Wright was one of the great collectors and publishers of Southern literature, and his Palaemon Press Limited brought out original works (and rare broadsides) by James Dickey, Eudora Welty, Reynolds Price, and Harry Crews, among many others. He had in common with Hannah an uncompromising stance on the importance of the sentence, as well as an appreciation for Bessie Smith and a fascination with Civil War history that bordered on the irresponsible. “You do beautiful work,” Hannah wrote him in the summer of ’81, and they’d soon resolved to work together.

It is only through Hannah’s letters to Wright that we are able to track the progress of Power and Light. Rather than write it as a screenplay, as Altman had surely intended, Hannah had written it as a fully realized treatment—a kind of hybrid between a novel and a script, complete with camera movements and musical cues. “I wrote Power and Light so much like a dream,” he wrote Wright in January 1982, “it is a real piece of art.” Though he admits it isn’t finished, he tells Wright he should publish it at Palaemon. “It may be a movie,” he adds, as if as an afterthought. “Things look good, except I’m so broke now.” He spent the rest of that year trying to wrestle the project into publishable shape—but the need to make an income kept getting in the way. For the spring semester of 1982, he took a writer-in-residence position at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, “in the heart of Dixie,” he wrote Wright that February, “trying to sabotage the rep and name of some asshole of old named Faulkner that they can’t shut up about around here.”

Hannah’s challenges were also chemical. “It’s been a bitch to write my first book straight sober,” he writes. “Very odd fun, even sometimes like work, which I swore long ago to avoid. I mean that was the whole point of writing anyway.” He apologizes for not having Power and Light ready, but explains that this is the way things will be with him: “What I want out of our dealings is total usage of you, fame, money, so that afterward you will be an empty husk and I will have a yacht and such pussy as to make you weep. Just so we get things out in the clear now.” He adds, as if to make up for his crack at Faulkner, “It’s good to be back to the wonderful ignorant beautiful South.”

As the months go by, Wright sends encouragement, money, and music (tapes that Hannah can write to). In return, Hannah stalls and tells him stories about, for instance, spending a night on Jimmy Buffett’s boat with Thomas McGuane: “I even snorted a bit of toot,” he says of the party, “which was clean and merry enough and did not make me want to drink.” His sobriety is a constant source of concern, but he claims to be winning the battle. “With such friends as you, I might never have the big humbling urge to drink ever again. Biggest thing I’ve got to fight is the nostalgia for the wild man in my thirties that I was and the fact that booze, unfortunately, will clear the lane for some real writing now and then.”

By November of ’82, Hannah vows, “Power and Light is so close, so close. If those fuckers at the school would just quit insisting I do something for the money they pay me, I’d have it there by Thanksgiving.” When he describes the project, it’s as though he’s already abandoned Altman’s vision and become preoccupied by the challenge of making it live up to his own standards as a piece of fiction. “I mean let’s make it a work of art,” he writes, “not simply another bestseller, movie [option], couple of million thing, what?” Within a couple months, he’s fully taken over the reins. “His was fine but more strictly visual,” he writes of Altman’s idea. “In this form I can get away with a little more head music.” By February, he’s finished. “God bless you, Captain, for your support,” he tells Wright. “I told you I was the biggest baby in the South, warned you.” According to Wright’s archives, Hannah was paid roughly $455 for the book, which was printed as a seventy-eight-page limited-edition hardback under the title Power and Light: A Novella for the Screen from an Idea by Robert Altman. (It would later appear in revised form in Captain Maximus.)

One of the strangest and rarest books in Hannah’s catalog, Power and Light is worth the trouble of seeking out, not only because it is the only tangible artifact of the author’s adventures in Hollywood, but also for its humor and formal uncertainty—a “novella for the screen” is an accurate description. As they’d originally planned, it’s a series of vignettes centering on working class women who work for Seattle’s public utility provider, bringing “power and light” to the city of fog and rain. There are rumblings of a plot that never entirely calcifies: the women begin receiving mysterious letters from an anonymous man; union troubles are invoked. There is brilliant dialogue one nevertheless has trouble imagining actors reciting convincingly: “You can’t see me real,” one character says. “You could put your head through the real me. I’m not too sturdy. I’m floating. I’m not even here. I think it runs in my family.” There are also odd and powerful non sequiturs: “Mists devolve around and appear to emanate from the grave of Jimi Hendrix,” begins one scene, which ends soon afterward, contributing nothing discernible to the story. The greatest of the non sequiturs, though, is a kind of prose poem, or essay-in-miniature—you can’t help but wonder what Altman made of it:

Behold the isolated walrus on a rock island. What is a walrus, what in hell is a walrus anyway? From front-on of its face, whiskers, we see the eternal furry mourning of the walrus. These sea eyes are deep and we study them like symbolist poetry. The walrus is the powerful sloth of lust. The sea-cow is now on another rock. What is a sea-cow? How does it go for the sea-cow? We range in and see the almost horrible perplexed creation of mammal and fish together. The mother is waddling for fish, off then nimble in the cold dark impossible water. The walrus guards the whole absurdity. He is so great and so expendable. So on with camera philosophy.Man, it is wet here and heavy in the air and it’s hard to fly, yak the seabirds.

Barry Hannah signs off. © The Stuart Wright Collection, East Carolina University.

Barry Hannah signs off. © The Stuart Wright Collection, East Carolina University.

In one of his final letters to Wright concerning the finished Power and Light, in late February of 1983, Hannah once again brings up its status as a possible film: “Elliott Lewitt, the producer for Ray, will be contacting you about a movie.” He finishes the letter with a characteristic Civil War vision: “Save your house, save your wife. Pull back and reload. They’re all coming at us. This time we come in with something new while they’re trying for Richmond.”

This was the first I had seen Hannah mention Lewitt, who still works as a producer in Hollywood, and so I wrote him asking about his years working with Hannah. Lewitt remembered them vividly; he was young and relatively inexperienced in the industry at the time. He had been bowled over by Airships when it was published, but when he read Ray he believed it had to be a film, and was just naive enough to think the project might slip through the cracks. “I liked that it was scattered, that it jumped around from time period to time period,” he said of the novel. “It’s a book about lost causes and it’s very cinematic, it seemed to be crying out to be made.”

He optioned the book and soon got to know Hannah well. “Barry told me he’d just done this thing with Altman, that he’d put him up for a while in Malibu. He’d paid him to write this book, Power and Light. He said, ‘I own this, Altman’s never going to make it.’ He didn’t think Altman was very happy with what he did. He gave me a copy of Power and Light and said if you want to make this, let’s do it. I told him I love everything you do, but let’s get Ray done first.” Lewitt commissioned a script from the writer Marjorie David. (“I thought Barry had better things to do than adapt his own book,” he explained.) There followed a period of several months in which the Ray screenplay made the rounds of the bigger Hollywood talent agencies, and the responses were largely positive. Jeff Berg, the chairman of ICM, read it and agreed with Lewitt’s opinion: it was crying out to be made.

“Once one big agent reads something and likes it, it has a way of coming to the attention of other people,” Lewitt said. In this case, Robert Altman’s agent was given a copy and, “there was this interesting moment when Bob came back into Barry’s life. He was very interested in directing the movie.” But Lewitt wasn't convinced. One Oscar-winning screenwriter who had once been close to Altman advised Lewitt, “Don’t go down that road. Bob’s gotten very lazy.” More importantly, he’d been meeting with Harold and Maude and Being There director Hal Ashby about the project, and Ashby seemed fully committed to the film. Lewitt also showed a copy to Sam Peckinpah, who loved it as well. (“Sam thought that Barry was a kindred spirit,” he remembered.) But, Lewitt said, “I was really taken with the idea of working with Hal Ashby” and Ashby, Hannah, and Lewitt began discussing casting for the project: Ed Harris was their favorite for the lead.

Lewitt spent a great deal of time with Hannah in California in the mid-eighties, the two of them waiting for something to happen. Hannah was a hit at L.A. parties. “People in Hollywood loved Barry,” Lewitt said. “He’s a charming Southerner, loquacious, he’d turn on that great Southern accent. He would be fabulous.” But most often these nights would end with Lewitt acting as designated driver for Hannah, who was plastered and rambling and lost. Hannah also soon grew disenchanted with the scene, which was full of people he found duplicitous and vampiric. “It was not a good place for Barry,” Lewitt said. “People in Hollywood inhale lies and exhale lies. People would say they liked his books and he never understood why nothing ever happened. I had to gently explain that it was because nobody was being honest.”

In 1988, Hal Ashby died unexpectedly at the age of fifty-nine, and Ray’s future was once again unclear. “There are moments when movies can get made, and then they pass,” Lewitt explained. “And unfortunately, all the forces are sometimes aligned against you.” In the end, Lewitt believes, Hannah was left slightly bruised by his brush with Hollywood. “He grew frustrated with everybody. He probably grew frustrated with me, honestly.” He was also hurt by Altman’s lack of enthusiasm for Power and Light, the film they’d developed together. According to Lewitt, “Altman basically set him up to write it, and then Altman was gone. He was onto something else. I remember Barry feeling like he had been left high and dry.”

In later years, Hannah would play off his Hollywood years as a kind of fluke or weird vacation. “I have a little experience,” he told one interviewer of the movie business, “but not enough to get my heart broken.” Lewitt, for his part, never entirely gave up on the projects. For years, other producers and agents dubbed him the “Duke of Darkness” for his advocacy of scripts like Ray and Denis Johnson’s Angels, another adaptation he pursued for decades. Talking to him about Hannah’s work, it’s clear that part of him still hasn’t completely abandoned hope. “I have a copy of Power and Light and every once in awhile I pull it out and look at it again,” he said. “And about six months ago I went and found a copy of the Ray script and read it again and I thought, this is a good script. Still! There’s such a great movie here and, you know—one day I’d love to make it.”

“Outskirts of the Southern Canon” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.