The Music of Kentucky

*Notes on the songs from our 19th Southern Music Issue CD featuring Kentucky*

By Oxford American

“The Piano Teacher,” by LaVon Van Williams Jr. Courtesy of the Hickory Museum of Art

On the first day of 1964, Thomas Hall, a twenty-seven-year-old writer, moved to Nashville. He came from a small town in Northeastern Kentucky called Olive Hill and he had written some popular songs that displayed his emerging talent, earning him a permanent invitation to Music City. By the end of the decade, Tom T. Hall was on his way to becoming country canonized, a Southern writer in the mode of Bobbie Gentry, Kris Kristofferson, and Johnny Cash—people called him “the Storyteller.” Many of his songs were inspired by characters and events he remembered from Kentucky: “Harper Valley P.T.A.,” “A Week in a Country Jail,” “Ballad of Forty Dollars,” “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died,” and “Homecoming,” with its arresting opening: I guess I should’ve written, Dad, to let you know that I was coming home / I’ve been gone so many years, I didn’t realize you had a phone.

“The thing that fascinated me most during my childhood were the people that I grew up with,” Hall writes in his 1979 autobiography. “I saw the whole environment of my early days as a large stage with parts being played by real people in real life.” Hall viewed the world as a great show and so his songs chronicled dramas of the everyday. In the early seventies, he began to go out story collecting, often driving north, back into Kentucky, to observe and meet real people in bars and diners and beside roads and rivers, taking notes that he’d later alchemize into songs like “Kentucky, February 27, 1971,” about a conversation with a retired farmer. “There were debts to pay for every song I wrote from my travels,” Hall writes. “I longed for the simplicity and the independence that was demonstrated by the people that I had left behind. I had to learn that we never escape who we are.”

This faculty, to be attuned to one’s surroundings and the ways in which they’re unique, to be rooted in the local, to be of a certain place—no matter if one permanently leaves it, like Richard Hell, or stays forever, like Rachel Grimes—is an elemental theme running through the Oxford American’s 19th Southern Music Issue, devoted to Kentucky. It’s manifest in every one of the songs and stories gathered here: the Commonwealth produces a particularly grounded cast of artists, writers, and musicians. And so it is that this Kentucky issue is populated with a striking abundance of place names. From the cities and college towns to the hollers and hills, these writers and artists seem to make it a point of “checking in,” as we say nowadays. Lexington, Louisville, Bowling Green, Paducah, Berea, Betsy Layne, Sassafras, Smokey Creek, Falmouth, Cutshin, Gray, Monkey’s Eyebrow, Paradise, Brightshade, Marrowbone. It’s in the water, we say when reaching to explain how so much of something so remarkable can come from the same place; in the case of Kentucky, seems we’d do better to say it’s in the bloodstream.

In his memoir, Hall explains why he was drawn back home after he’d made it big: “I was awed by these people, and I admired them and feared them. I was also one of them.” He was in search of his songs, and he was finding himself.

—Maxwell George

1 “BE PROUD OF THE GRAY IN YOUR HAIR”

Dave Evans

This past June, the Commonwealth of Kentucky—indeed the common wealth of the world—suffered an incalculable loss when Dave Evans, master bluegrass songwriter and nonpareil banjo picker in the traditional mountain style, passed away at the age of sixty-six. Readers of this magazine will be familiar with Evans’s life (his road years, his prison years, his sick years) and legacy (he claimed to have written—and been robbed of—“Rocky Top”) from Lee Johnson’s 2013 profile of the man who “pours everything he has into three simple chords, and then lets it overflow.” Evans was originally from Columbus, Ohio, but he lived and made music and died and is buried and mourned in Eastern Kentucky. On “Be Proud of the Gray in Your Hair”—a selection recommended by Evans’s longtime label Rebel Records—you can hear the versatility and vitality he could summon from his instrument, words, and voice. Johnson offered an unimpeachable assessment of his talents: “That’s why you won’t hear Evans songs at even some of the hottest bluegrass jams: they make amateurs out of professionals.”

From the archive: Lee Johnson on Dave Evans.

2 “SEA STORIES”

Sturgill Simpson

“It’s tense and dramatic one moment, the next, languid and dreamy,” writes Leesa Cross-Smith of Sturgill Simpson’s A Sailor’s Guide to Earth. “It’s awash with blue, a country concept album—earnest letters to his wife and son, sea-moonlighting as songs.” Inspired by his three years in the Navy, “Sea Stories” is the album’s “pirate song,” as Simpson has labeled it—“what they call a chantey.” It’s a rocking chronicle of a young sailor’s life, from enlisting in the Navy and traveling overseas to getting kicked out and spending a year “trying to score from a futon life raft on the floor” (with a sardonic final line, though it’s delivered in what sounds like a triumphant shout, in which the sailor observes that “flying high beats dying for lies in a politician’s war”). A Sailor’s Guide to Earth starts with a birth, and the past year has also felt like something of a new beginning for Jackson, Kentucky–native Simpson. For years he has been well regarded as a radical country songwriter. But then, on the strength of his soul- and psychedelic-rock-inspired third record, he was catapulted to wider fame. In 2016, he was nominated—alongside Adele, Beyoncé, Justin Bieber, and Drake—for an Album of the Year Grammy. At the ceremony, he was fittingly introduced by fellow Kentuckian Dwight Yoakam, who quoted Duke Ellington’s maxim that “there are only two kinds of music: good music and the other kind.” Simpson’s is indeed the former.

In the magazine: Leesa Cross-Smith on Sturgill Simpson.

3 “CAN I SAY IT AGAIN”

Soul Walkers

When they started making music in 1967, the Soul Walkers were just three teenage boys—cousins Eugene Hayden and Michael Black, and their neighbor Bruce Griffith—living in the Mechanicsville neighborhood of Owensboro, Kentucky. Still too young to drive, they lugged their gear on foot, literally walking from practice to practice, and gig to gig. Once the boys had learned their way around their instruments, Bruce recruited his cousin Johnny McNary to pitch in on vocals, and soon the Soul Walkers had made enough noise at local gigs—often playing to crowds of teenagers in driveways—to attract the attention of Charles Winston, James Palmer Jackson, and Ben Griffin, older musicians who joined the band. For a while, they enjoyed modest success, touring military bases and nightclubs and recording a handful of songs for the budding Cardinal Studio; on the imploring “Can I Say It Again,” you can hear the obvious influence of the Jackson 5. The momentum wouldn’t last, though, and infighting led the Soul Walkers to dissolve in 1973. By then, the founders had barely reached their twenties, leaving only a few funky singles to mark a brief flash of regional fame.

4 “BY THE OHIO”

Joan Shelley

When Joan Shelley sings “I belong to you,” the last word drawn out, on this song’s refrain—her voice tender, restrained, and just on the brink of mournful—she’s declaring her desire for, and fidelity to, an unnamed lover. But in the context of her biography, the lyric sounds just as much like a pledge to the titular river itself. Shelley was raised outside Louisville and lives in the city today, and her music has long been anchored in Northern Kentucky’s particular geography: the mountains giving way to the river and to plains shot-through with blue. “By the Ohio” comes from early in Shelley’s career—it’s the final track on 2012’s Ginko, produced by Louisville compatriot Daniel Martin Moore—but its devotion to landscape has been a mainstay of her songwriting all the way up through the remarkable self-titled album she released in May 2017. On Joan Shelley (produced by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy), you’ll find her usual gripping, unadorned intimacy, accompanied by a slightly fuller sound that shows just how clear and deep her waters run.

5 “RAINBOWS”

James Lindsey FEAT. Cicily Bullard

“When Lindsey raps ‘I’m talking rainbows,’ I think he must be talking black joy. I think he must be talking the kind of rainbow you see in the shimmer-swirl of color that floats over the curve of a soap bubble. How alike they are, soap bubbles and black joy: Beautiful. Carefree. Tenuous.”

6 “BEACON”

Matt Duncan

“Igot friends in New York City,” opens Matt Duncan on the title track of his 2010 debut album, “’cause everyone I know left town,” i.e., Lexington, where the multi-instrumentalist and songwriter graduated from Lafayette High and went on to play in popular local band the Parlour Boys. Another musician on the Lexington scene, Stephen Trask—who’d had a huge Off-Broadway hit as the composer and lyricist for Hedwig and the Angry Inch and frequently traveled back to New York—was a fan of the band and offered assistance, but “we were too young and dumb to be helped,” Duncan says. A few years later, Beacon received positive reviews locally, and in 2014, shortly after Duncan had released his second album, Soft Times, on Hop Hop Records, he got a call from New York. Producers were mounting Hedwig on Broadway, with Neil Patrick Harris in the title role, and Trask pulled Duncan northward for a spot on bass in the house glam-rock band. Now that the Tony-winning production’s run in New York and the subsequent tour have ended (after some seven hundred performances), Duncan is back fronting a new band, albeit one he’s very familiar with; backing him on his newly released rock album, The Slowest Walkers in Manhattan, are his bandmates from Hedwig. He’s staying on in New York, but Kentucky’s never far from his mind. He’s working on his own musical with Kentucky playwright Kelli Lynn Woodend and still plays “Beacon”—his “cheerleading song for all the expats,” he calls it—but admits it’s a “strange feeling playing that song here.”

7 “IT’S ME NOT YOU”

The Torques

In the liner notes to their 1967 self-titled album—recorded live on New Year’s Eve, 1966—the Torques are described as showing “real versatility in reproducing the standard vibrations of the big name groups, along with their own psychedelic expressions.” Formed in 1960 by a group of guys from Lexington’s Henry Clay High School, the Torques spent nearly a decade as one of the most popular bands in their hometown, playing gigs at frat parties and dance clubs across the region. The thumping “It’s Me Not You,” released as a single on Lexington’s Lemco label in 1965, is performed in a gleeful and cacophonous garage-rock style; it’s not hard to imagine the young musicians geeking out over the Kinks and other “big name groups” of the day. The Torques broke up in the late sixties when several band members joined the service. One was lead singer Phil Copeland, a native of Hazard, Kentucky, who attended UK on a trumpet scholarship. When Copeland came back to Lexington, he stayed in the music business, singing in nightclubs and writing jingles. He would go on to win Emmy Awards for composition work on Guiding Light and ESPN’s SportsCentury. (Copeland is not the only big-time TV composer from Kentucky. Louisville’s Jonathan Wolff wrote one of the most recognizable show themes ever, Seinfeld’s ubiquitous slap-bass intro.) The Torques played a reunion concert in 1996, on the occasion of Copeland’s fiftieth birthday. They’ve kept the band together ever since.

8 “ME HUNGRY”

King Kong

“Me Hungry, King Kong’s third LP and overlooked magnum opus, came out in 1995. It is a concept album that never strays from its narrative—the rare rock opera to subvert the corniness and pretentiousness inherent in the genre. Across nine songs, the story involves a caveman’s love affair with a yak (with a crow on its back), which sours as our protagonist learns to hunt, meets a cavewoman, and, in what amounts to perhaps the cruelest breakup documented in American song, eventually slays the yak for supper.”

9 “MY OLD DRUNK FRIEND”

Freakwater

Read Erik Reece’s “Louisville Lip” and you’ll learn that, despite the “raucous post-punk” company they kept in the nineties, Freakwater was “at their core an old-time string band.” It doesn’t take ten seconds of “My Old Drunk Friend,” from 1993’s Feels Like the Third Time, to hear that he’s right. Catherine Irwin and Janet Beveridge Bean’s harmonies are spare enough to seem instantly old-fashioned—their voices accompanied only by tinny, muted strings. Bean’s high, sweet lilt cuts through Irwin’s gravelly melody line like water that’s been running over river rocks for centuries: clear and certain and true. The song perfectly illustrates how Freakwater conflated the romantic and the banal to produce what Reece calls the band’s “savage sense of irony.” The women sing: “And the streetlights shine down on the bottles we have broken ’til the road is paved with diamonds from a thousand lost love tokens.” In an artificial glow, drunkenly shattered glass is transformed into precious gems ground into the rubble of the street. The image is weirdly beautiful, a little bleak, and darkly deadpan-funny.

In the magazine: Erik Reece on Freakwater.

10 “CAMP NELSON BLUES”

Booker Orchestra

“Although any number of floating ‘blues’ verses could be sung to its AAB form, ‘Camp Nelson Blues’ isn’t much of a blues by the genre standards we apply today. Instead it reflects a wide swath of the Bookers’ musical predilections, synthesizing, for a few wonderful minutes, a necessarily wide repertoire that would have appealed to a diversity of audiences—town and country, white and black—in a moment in history when the old-time black string band was fast falling out of fashion.”

11 “I’M GOING TO ORGANIZE, BABY MINE”

Sarah Ogan Gunning

“In contrast to the music of her siblings, there’s a tenderness and vulnerability to Gunning’s songs, which are drawn from her life in the way of gospel testimonies. As Guthrie, who recorded his own version of ‘I’m Going to Organize,’ put it, ‘Sarah’s homemade songs and speeches, made up from actual experience, are deadlier and stronger than rifle bullets, and have cut a wider swath than a machine gun could.’”

12 “SHUT UP IN THE MINES OF COAL CREEK”

Bret Ratliff

Versions of this mournful mountain ballad were performed almost immediately after the event that inspired it more than a century ago—the Fraterville Mine explosion of 1902. (Alan Lomax recorded Nell Harrell singing and playing one in 1937, and the New Lost City Ramblers did an a cappella version in 1968.) Brett Ratliff, who included the song on his most recent album, Gone Boy, says he learned this particular melody from banjo player George Gibson of Knott County. Early on, Ratliff, who comes from a family of miners and musicians in Van Lear, developed his ear for mountain music on WMMT, the community radio station run by Appalshop (Jeffrey A. Keith profiles “Real People Radio” in this issue). “The voices that came across the airwaves were like mine,” Ratliff says, and he learned songs by recording the station’s shows and replaying them over and over. After studying music production and performance in college, he eventually ended up at WMMT himself as station manager. Now, in addition to recording and performing his own and historical compositions, Ratliff works as director of cultural heritage programs at the Hindman Settlement School in Knott County.

13 “WOMEN’S PRISON”

Loretta Lynn

Loretta Lynn’s rise to fame is as legendary as that of any star alive: born in Butcher Holler in Van Lear and raised in a one-room cabin; surrounded by a large family who loved music and the Grand Ole Opry; married as a teenager to Oliver “Doolittle” Lynn, who bought his wife her first guitar. It was 1960 when she released her debut single, “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” and she’d go on to sell millions of records and have sixteen No. 1 hits. Lynn is best known for her bold (and famously banned) singles like “Fist City,” written fifty years ago, in which the lyrics advise a flirting woman to keep away from the protagonist’s man—or else. (“If you don’t wanna go to Fist City you’d better detour ’round my town.”) In this issue, Marianne Worthington writes of discovering Lynn’s music through her appearances on television and of loving it for a lifetime, drawn to “the brutal whack of honest lyrics filled with bad luck and bad choices, and, always, a woman’s raw voice holding it all together.” The harrowing “Women’s Prison,” off 2004’s Van Lear Rose—Lynn’s first album written entirely by her, recorded over ten days in an East Nashville living room in collaboration with Jack White—is a prime example of this tough and fury-soaked songwriting. These days, we’ve grown accustomed to country stars like Miranda Lambert and Brandy Clark—both of whom have cited Lynn’s influence on their careers—singing of vindictive violence against no-good men. Still, it’s hard not to gasp at the ferocious climax of “Women’s Prison.” Lynn sings of the protagonist being strapped into the electric chair. Her death imminent, the song ends with a near-whispered rendition of “Amazing Grace”—so this is a redemption story, after all. Cue the grinding guitars, and then the glowing praise. In 2005, Van Lear Rose won a Grammy for Best Country Album. It was Lynn’s first in the category, more than half a century after she left Butcher Holler.

In the magazine: Marianne Worthington on Loretta Lynn.

14 “SHADY GROVE”

Jean Ritchie

Jean Ritchie is as much considered the “Mother of Folk” for her own music as she is for elevating the genre in the American consciousness. She authored books about the Appalachian dulcimer, started a company with her husband to build the instrument, traveled the world singing and studying the music, and recorded The Appalachian Dulcimer: An Instructional Record, from which this version of her traditional staple, “Shady Grove,” is taken. “Shady Grove,” which has as many as three hundred lyrical variations, was passed down through oral tradition and is thought to date back to the seventeenth century. (On a Fulbright scholarship in 1952, Ritchie tracked American ballads to their Irish and Scottish roots.) It became popular in the mountains of Kentucky around the time of the Civil War, perhaps explaining why the courting song is so sonically drenched in sorrow. In Ritchie’s version, content meets form: her dulcimer is tuned to a dirge-y Aeolian mode, way over yonder in the minor key. The song is evocative of its place (“shoes and stockings in her hand / little bare feet on the floor”) and full of longing (“wished I had a big fine horse / and corn to feed him on”); Ritchie’s voice seems barely able to sync with her strumming. She preferred to pick her instrument with a whittled-down wing feather from a goose or turkey, but “if you can’t find a feather right away,” she suggests on “Simple Thumb Strum,” another track on The Appalachian Dulcimer, “take a stay out of a man’s shirt collar and whittle that down.” In this version, more Celtic than cowboy, it’s as if Ritchie’s voice pulls the quill along, ahead of the strumming, racing just fast enough to maintain the drone all the way back to Shady Grove.

15 “DOWN TO THE BONE”

Legendary Shack Shakers

The name Legendary Shack Shakers does not ring with the slightest hyperbole for anyone who has witnessed their live performance. Onstage, the Paducah band’s principal songwriter, front man, and harmonica player Col. J. D. Wilkes becomes possessed, gyrating and gesturing, climbing into the rafters, licking himself and others— putting on a show—like the bastard offspring of Iggy Pop, Tom Waits, and a riled-up Banta rooster. Offstage, Wilkes’s immense creativity is showcased in his work as an illustrator, filmmaker, and writer steeped in his homeplace in the most western region of Kentucky, known as Jackson Purchase. (In 2013, Wilkes published Barn Dances & Jamborees Across Kentucky, a comprehensive history of rural music-making across the Commonwealth.) On “Down to the Bone” from the aptly titled 2015 album The Southern Surreal, the Shack Shakers conjure an afterlife where the earthly remains are transmogrified into instruments—“gut strings strung to an old-time crooked tone”—fading in and out on a spooky nighttime soundscape. Wilkes is obsessed by the beguiling forces of the natural world. In his novel The Vine That Ate the South, the narrator speaks of the forest trees as giant witching rods “that lure me inward” like dowsing wands for the human spirit. “And what is our soul,” Wilkes writes, “but a fluid thing too, a flowing power that tunnels through our veins like currents through underground channels, like the very well-waters sought by the diviner?”

16 “RICH WIFE FULL OF HAPPINESS”

Bonnie “Prince” Billy

Louisville’s Will Oldham was a serious actor before he took up music—around 1990, when he was twenty—and this fact is helpful to understanding his catalog of idiosyncratic, searching songs. He is interested in embodying emotions through the invention of character and so for almost thirty years now he has avoided injecting the personal into his music, ducked any whiff of the biographical in interviews, and released his albums under various enigmatic guises, most frequently as Bonnie “Prince” Billy. “The songs are not meant to be real life,” he told Alan Licht in the book-length interview Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy. “They’re meant to have a psychic, rather than factual, bearing on the listener. . . . It’s real life of the imagination.” This is not to suggest that his music is without intimacy or reach; the defining performance of Johnny Cash’s late-career resurgence is the haunting recording of Oldham’s “I See a Darkness,” and in 2016 Oldham co-wrote three songs on John Legend’s Darkness and Light. “Rich Wife Full of Happiness” is from Ease Down the Road, released in 2001, a collaborative period (among others, David Pajo of Slint and King Kong appears on the song, and the bridge harmony belongs to Freakwater’s Catherine Irwin). It’s a love song in Oldham’s inimitable style, the lyrics traveling a circuitous route from obscure—“She wears my favor and shows it around”—to quizzical—“The dog licks the shark dry in your photographing”—to the unambiguous final image of joy.

17 “FORSAKEN LOVER”

The Phipps Family

If you listen even briefly to any song the Phipps Family recorded, you’ll understand why they’re so often mentioned in the same breath as the Carter Family. (Silas House mines their intertwined histories in his essay “Watershed.”) The Phipps Family discography is largely populated by familiar ballads, old standards, and traditional hymns; “Forsaken Lover” is a rare original song. Here, the Phippses’ harmonies sound as innate as their family bond, and a relatively up-tempo melody belies lonely, grief-stricken lyrics. The contrast between the two feels increasingly apparent as the song goes on, and by the final line—when Kathleen and A. L. Phipps sing, “How my heart is now breaking no one will ever know / I’ll wear a smile forever, wherever I go”—the slight dissonance between music and lyrics seems like the perfect illustration of a forlorn, abandoned lover pretending with all her might that she’s never been happier to find herself alone.

In the magazine: Silas House on the Phipps Family.

18 “I’M A POOR LI’L ORPHAN IN THIS WORL’”

Julia Perry (performed by Shirley Verrett)

Born in Lexington in 1924, Julia Perry was one of the most prolific African-American composers of the twentieth century, and probably the most underappreciated. Though she lived to be only fifty-five—after a stroke, she spent the last years of her life paralyzed on her dominant side, and trained herself to compose with solely her left hand—Perry produced nearly eighty compositions, including twelve symphonies and an opera adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” complete with an Italian libretto. (Scholar J. Michele Edwards writes that Perry’s “triple marginalized position as an African American, a woman and a person with disabilities cannot be overlooked as a factor contributing to the assessment of her work by the musical establishment.”) In the 1950s, Perry worked primarily from Europe, creating arrangements for spirituals. “I’m a Poor Li’l Orphan in this Worl’” is the synthesis of her classical training and her African-American roots, a sparse arrangement fit for both opera hall and place of worship, and requiring a singer of extraordinary skill to properly emote the song’s inherent sorrow. This recording, an early-career performance by New Orleans mezzo-soprano Shirley Verrett, does just that, revealing how the spiritual and the opera share an essential sense of drama.

19 “SOME DARK HOLLER”

Dwight Yoakam FEAT. the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

The trajectory of “Some Dark Holler” is as full of unexpected forks as Kentucky’s mountain roads. The song was recorded under the title “Dark Hollow” by Bill Browning in 1958, the B-side for his single “Borned with the Blues,” but it has strong melodic ties to Appalachian standards like “East Virginia Blues” that suggest its roots go back even further. The Grateful Dead released a version on their live album History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear’s Choice) in 1973 and went on to regularly perform a variety of acoustic and electric renditions in the ensuing years. Their frequent covers unexpectedly popularized the song for a much wider audience, but it’s also been recorded by a number of bluegrass artists, from Ralph Stanley to David Grisman. Dwight Yoakam’s version, released first on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s 2002 album Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume III, and then again on 2004’s Dwight’s Used Records, confirms the song’s continuing relevance in contemporary country music. In “That Place in the Middle,” Ronni Lundy recounts her decades-old appreciation for Yoakam’s music—and his “passion for place so searing it transcends the limits of time.”

20 “IT NEVER STOPPED IN MY HOME TOWN”

Les McCann

Les McCann gained mainstream fame with a live performance at Switzerland’s Montreux Jazz Festival in 1969, playing piano and singing Eugene McDaniels’s protest anthem “Compared to What,” accompanied by saxophonist Eddie Harris. The song, which rails against the Vietnam War and at one point refers to “poor dumb rednecks rolling logs,” reached No. 85 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart, and the album it opened, Swiss Movement, went gold. Four years later, on the heels of another live album from Montreux, McCann went into the studio—alone except for an occasional percussionist—and constructed an album using almost solely electronic effects: keyboards, synthesizer, and overdubbing. The engineer, Robert Liftin, essentially invented a 32-track machine (by combining two 16-track machines) so McCann could record as many overdubs as he wanted. McCann says in the liner notes to Layers, the resulting album: “I began playing on the piano what I had been hearing in my head. They came out in pattern after pattern—unrolling in endless layers, one after another.” Much of what he downloaded from his head were memories of growing up in Lexington, where he’d see who was playing the Lyric Theatre (like Louis Armstrong), wait at the hotel, and “meet the bus, load their bags, bring ’em up, and they’d all tip me,” as he tells Harmony Holiday in a Q&A. (McCann grew up on Eastern Avenue, the same street as the composer Julia Perry.) Side B of Layers is called Songs from My Childhood, and the “It” in “It Never Stopped in My Home Town” could be his love of music or maybe a train—a very electronic one—rolling and “unrolling” through Lexington, leading him out of town to the wider world.

In the magazine: Harmony Holiday in conversation with Les McCann.

21 “BLIND”

The Pleasure Unit

As East Coast “tween and teen” transplants to Louisville, brothers Kareem and Jaleel Bunton (who’d moved from Stamford, Connecticut) befriended Torbitt Schwartz (from Brooklyn). They all lived in the Highlands neighborhood, two blocks off Bardstown Road, “the hub of all that was hip in Louisville,” Kareem remembers. There, the three came of age, growing into “tried and true scenester dudes,” in thrall to the older bands fueling Louisville’s nationally renowned punk and hardcore community and captivated by the records at ear X-tacy, the infamous used record store. After the older Kareem left for college in Iowa City, Jaleel and Torbitt formed a band of their own, the short-lived Navin R. Johnson. Jaleel eventually followed his brother to Iowa, where they formed the Pleasure Unit. In 1995, they moved to Brooklyn and reconnected with Torbitt, who joined the band (along with Japanese scenester Tada Hirano of Blonde Redhead and Ultra Bide). Once again, the three found themselves witnesses to a vital moment—the return of New York rock & roll—and this time they weren’t kids on the fringes but artists at the very center. The Pleasure Unit rehearsed in a basement on Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side. In 2000, they recorded an album in an abandoned theater. Their shows were popular (once an old Kentucky hero, Britt Walford, formerly of Slint, came to see them) and members of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, and VHS or Beta (which formed in Louisville) counted themselves as fans. The Pleasure Unit never broke like their contemporaries, but “Blind” is a testament to the influence they had on the scene, with a bridge that sounds like a TV on the Radio outtake, recorded a year before that band was founded. Today, Jaleel is a longtime member of TV on the Radio, Kareem is the principal in On High, and Torbitt is a producer with Run the Jewels, with whom the Buntons have collaborated. Reflecting on what their teenage years in Louisville instilled in them, Kareem said, “No one makes selfish music there,” an ethos that still surprises people in New York. He also put it in Kentucky terms: “When we’re on your basketball team, we pass.”

22 “WONDROUS LOVE”

Pine Mountain Girls’ Octet

By the time the Lomaxes recorded them, the octet had recently completed two long concert tours, in November 1936 and May 1937. The former had taken them through the Midwest, where they made an appearance at Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ford’s weekly Friday night hoedown at the Ford Company’s research center in Dearborn, Michigan; the latter included a performance at the White House for the Roosevelts and two hundred fifty guests.

Read an essay on this song and “Pretty Polly” by Nathan Salsburg.

23 “PRETTY POLLY”

Locust Grove Octet

An Oxford American exclusive recording

The Louisville trio Maiden Radio—Cheyenne Marie Mize, Julia Purcell, and Joan Shelley—took the reins on gathering a contemporary octet of Kentucky women, inviting Linda Jean Stokley and Montana Hobbs of the Local Honeys, Heather Summers and Anna Krippenstapel of the Other Years, and Sarah Wood to join them. They recorded their version at Louisville’s Locust Grove in August 2017. The text—past the first two verses—is a composite of their own.

Read an essay on this song and “Wondrous Love” by Nathan Salsburg.

24 “CANCION MIXTECA”

Harry Dean Stanton

When actor Harry Dean Stanton passed away at ninety-one in September, many of us revisited Paris, Texas, the 1984 Wim Wenders film in which he featured as a Lone Star drifter. It’s the character that will probably remain his defining performance, though Stanton’s oeuvre is deep with unforgettable scene-stealing turns, from Alien to The Green Mile. He was born in West Irvine, Kentucky, but his family moved to Lexington, where he went to high school—at Lafayette, which Matt Duncan and Richard Hell would attend decades later—and enrolled at UK on the GI Bill after serving in the Navy in the Pacific during World War II. After discovering acting, he quit college to move to California in 1949. “I remember deciding whether I wanted to be a singer or an actor, because I was always singing,” he remembered in Crossing Mulholland, one of the documentaries about his life. “And I thought if I could be an actor, I could do all of it.” And so he did, often singing onscreen. “Cancion Mixteca,” which appears in Paris, Texas during a nostalgic montage, is a lament for Southern Mexico, composed a hundred years ago by a homesick José López Alvarez. But Stanton inhabits it as naturally as if it were written about Central Kentucky. As he notes in this recording from his only proper album, 2014’s Partly Fiction, “I see it as, when you’re truly at home there’s no more suffering . . . crying to get back to where you come from.”

25 “EIGHTS”

Rachel Grimes

Grimes released “Eights” as a single in early 2017, then expanded the piano étude to include strings and guitars. Renamed “A New Land,” it became the final piece in the as-yet-unreleased folk opera and film titled The Way Forth: Grimes’s intuitive, associative interrogation of Kentucky’s Bluegrass region from its settlement to the present.

26 “LOVE IS STRANGE” (LIVE)

The Everly Brothers

“They were the best duet singers I ever heard,” said Brian Wilson about the Everly Brothers (as recounted by Will Stephenson in “Living Too Close to the Ground”), and this 1970 live cut of “Love Is Strange” puts their collaborative powers on full display. More raucous than the pop version that appeared on Beat and Soul in 1965, the recording is dense with the heady energy of their live show and the irreplaceable intimacy of these brothers from a family of Muhlenberg County miners and musicians. “Love Is Strange” has its own Kentucky legacy, too: the song was a smash hit for pop duo Mickey & Sylvia in 1956; that’s Mickey “Guitar” Baker, the orphan from Louisville who helped create the earliest rock & roll music, though he is less recognized than contemporaries like Bo Diddley (a credited writer on “Love Is Strange,” under his then-wife’s name, Ethel Smith McDaniel). This later Everly performance eschews the song’s usual tenderhearted interlude of spoken dialogue and instead launches directly into the line baby, oh sweet baby, please come home—so that Don and Phil never actually speak to one another—and only in hindsight does this fact seem like an indication of something amiss. By the time of this performance, Don was preparing to release an ill-fated solo album and a few years later the duo would split in a dramatic public breakup. Singing together here, though, the Everly Brothers sound so inextricably linked it’s difficult to imagine a dissolution, their perfect harmony in the midst of discord providing lasting evidence that love is, in fact, inexplicable and strange.

In the magazine: Will Stephenson on the Everly Brothers.

27 “Y’ALL COME”

Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys

If the “Father of Bluegrass” and Kentucky’s proudest son can finish his show for more than a quarter century with “Y’All Come,” then so, too, shall we. This take, recorded live in Boston on Halloween in 1964, features Bill Monroe on vocals and mandolin, Peter Rowan on guitar, Bill Keith on banjo, Tex Logan on fiddle, and Everett Allen Lilly on bass. By the time of this recording, Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs had already parted ways with Monroe, forging lucrative careers that in the previous decade had superseded the man himself. Poor management, which failed to introduce Monroe to the next generation of bluegrass listeners, many of whom were coming to the music through the Greenwich Village folk revival, caused Monroe financial hardship. While Flatt and Scruggs were commanding thousands of dollars per show, Monroe toured for a time without a full band, paying local musicians who knew his repertoire to sit in. By 1964, however, Monroe had collected a band of men who came to be known as some of bluegrass’s heaviest hitters. “Y’All Come,” while brief, showcases some of the best of what Monroe and his band had to offer: tight harmonies and call-and-response; Keith’s eponymous style of banjo; and Monroe right up on the mic, frenetically picking out each note as his left hand ran up and down the fretboard. In his high tenor, the timbre of Kentucky, Monroe finished the night singing

Y’all come

(Y’all Come)

Oh you all come see us now and then

BONUS TRACKS

“ALL BY MYSELF”

Kelsey Waldon

Hailing from Monkey’s Eyebrow, Kentucky, Kelsey Waldon is a young country singer cut from an old cloth. Like her predecessors Loretta Lynn and the Judds, Waldon writes her own songs and plays her own guitar, charming listeners by injecting personality into her music. The opening verse of “All By Myself” is a nod to Appalachia, an acoustic instrument backing a singular, note-bending voice. Though Waldon is less interested in kitsch and irony, she is to Kentucky what Kacey Musgraves is to Texas, taking the tradition of the past and repackaging it to suit the audience of today. “I don’t have to make my mind up with anybody else / ’Cuz I can be me all by myself” is third-wave Loretta.

“A FEW MORE MILES”

Ben Sollee & Daniel Martin Moore

In 2010, singer-songwriter Daniel Martin Moore and cellist Ben Sollee, clear-voiced and clear-eyed Kentucky virtuosi, collaborated on an album called Dear Companion, a beautiful cri de coeur against the desecration of the state’s landscape by mountaintop-removal mining. A new song in the cycle, “A Few More Miles,” celebrates a victory for the Wilson Creek community in Floyd County against a coal company’s violation of the land. “Mountains are still disappearing,” write Jason Howard and Silas House about the artists’ project, and “even though they’re up against billionaire corporations, they have two things in their favor: words and music. There’s power in art and community, and that’s what Ben and Daniel have given us.”

The Oxford American’s 2017 Southern Music Issue CD would not have been possible without the generosity of the creators and rights holders of these songs. Liner notes by Eliza Borné, Molly McCully Brown, Maxwell George, Jay Jennings, and Sara A. Lewis. This issue is especially indebted to two Kentuckians, Rebecca Gayle Howell and Nathan Salsburg.

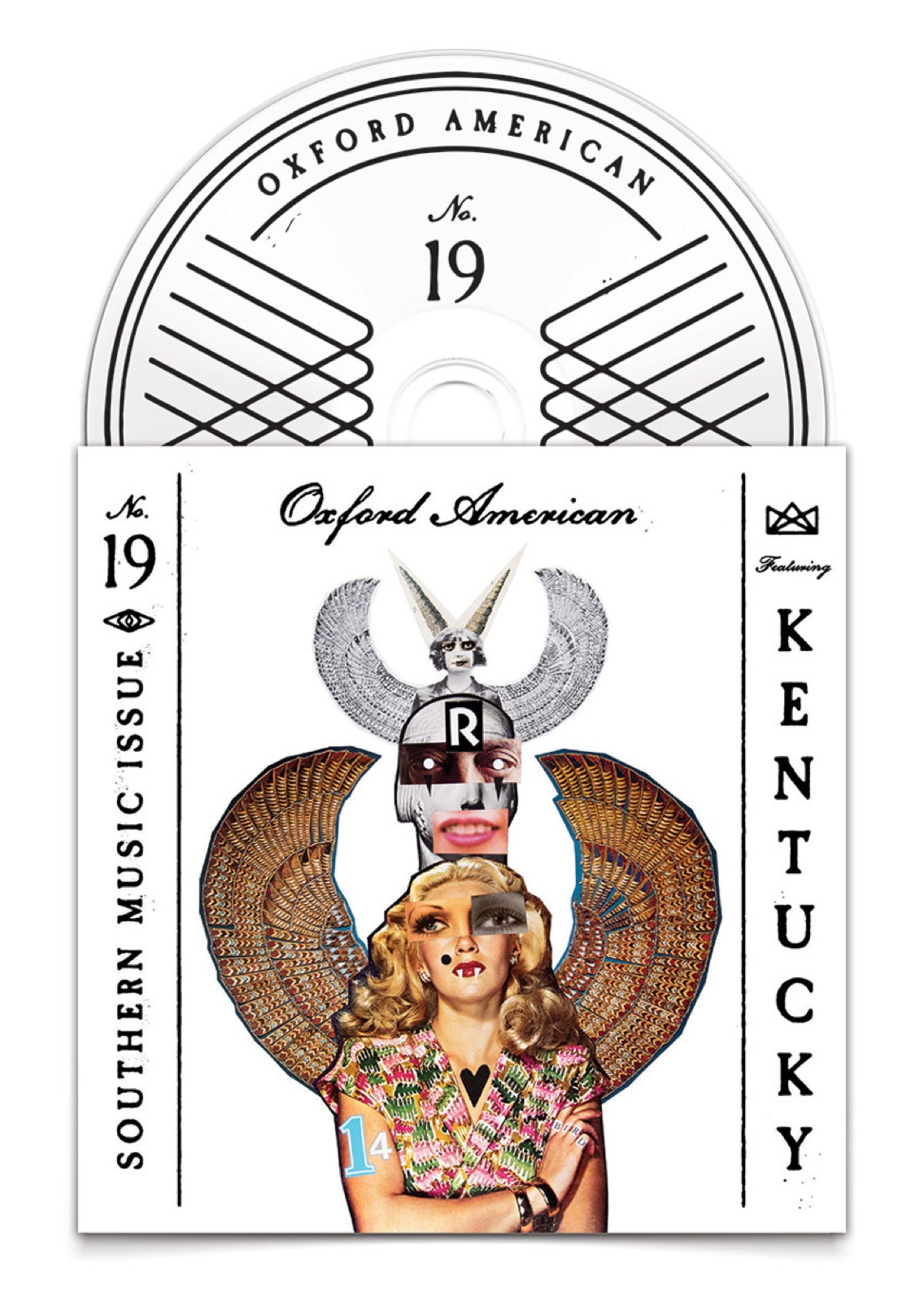

The issue includes a 160-page magazine and a 27-song CD + a free download with bonus tracks.