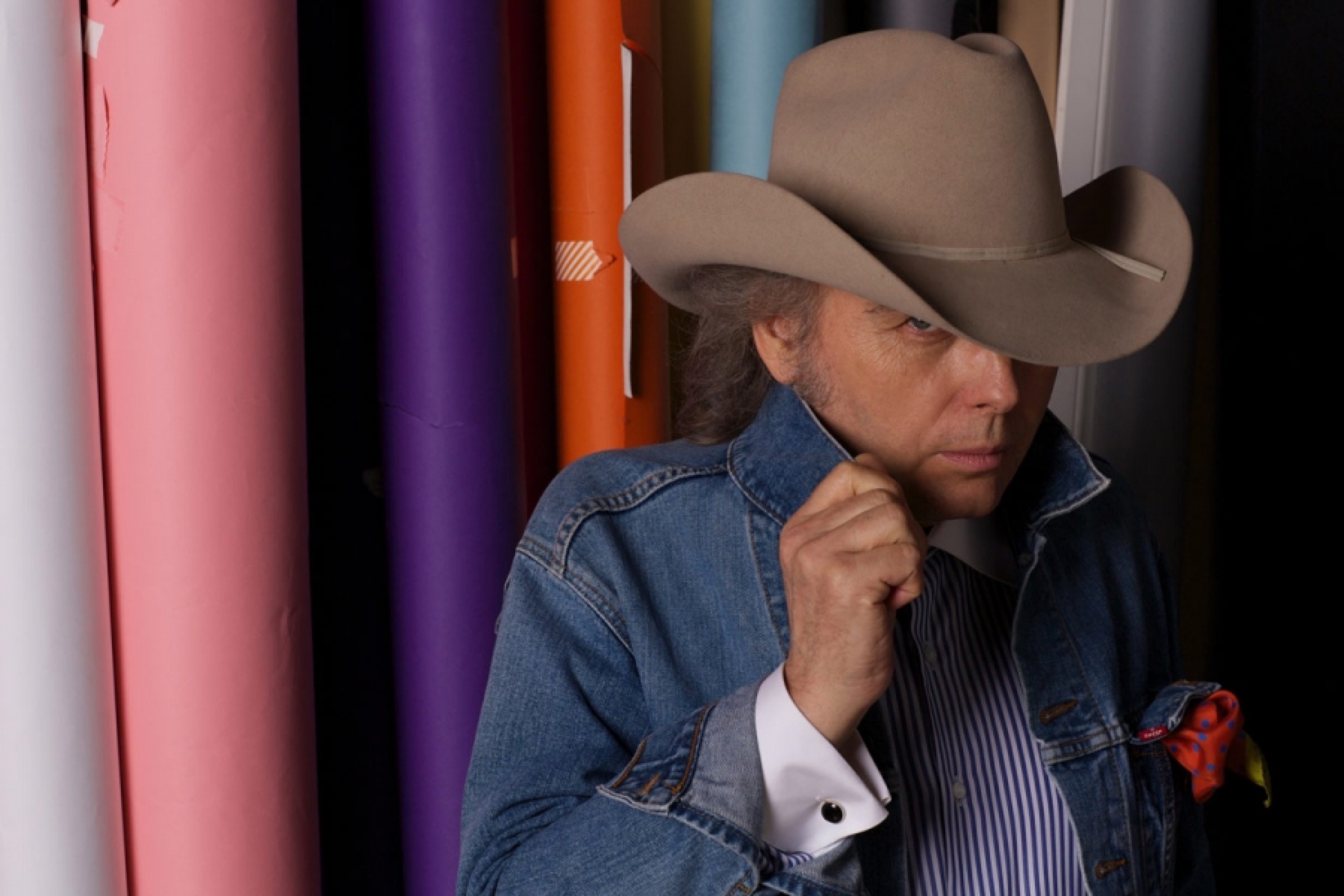

Photo by Emily Joyce

That Place in the Middle

By Ronni Lundy

July 15, 2017. Even with AC running and an icy beer in my hand, the Georgia Theatre in Athens, packed with standing bodies, felt as muggy as the night outside. My friend and I were next to the sound booth (“The better to hear you with, my dear”) and although almost half the sold-out audience was my age, I was a little anxious, wondering if the night’s concert by Dwight Yoakam was going to leave me feeling like Wendy at the end of Peter Pan—too old for the adventure but too full of memories to not care. To occupy my mind elsewhere, I pulled out a pad of paper and began to write down the playlist from the preshow tape: The Everlys. Buck. Monroe. The Everlys again. Three out of four from Kentucky. Yeah, maybe I did still belong here.

The young woman next to me said her boyfriend wanted to know what I was writing. I answered vaguely then asked if it was her first time to see Dwight. She grinned and told me she saw him a year ago. She explained: “I was a little reluctant to go, because, well, you know, he’s ‘older.’ But, oh man, he put on such a show!”

I asked how old she was. Thirty.

Dwight Yoakam was twenty-nine in the spring of 1986 when his debut LP, Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc. Etc., started to climb the country music charts. I was the thirty-six-year-old pop music reviewer for Louisville’s Courier-Journal, which was Kentucky’s largest newspaper then—and still a damn good one. Dwight’s actual age came as a surprise because in the hot honky-tonk photographs that heralded his launch (and for many years thereafter) he looked hardly a day over nineteen. I remember an early image that landed on my desk: Dwight stretched out, lanky and pouting, across the backseat of what I assumed was an old convertible Cadillac, cowboy hat low on his forehead, boots high on the door sill. It was all a little too James Dean for me. That and the fact that he’d played his way out through the L.A. punk scene (nobody much mentioned back then that he’d started in California cowboy bars and it took nine years) made me even more dubious.

The writer of the short magazine spot that accompanied the photo was skeptical, too. He reported that while Yoakam surely had a twang and a birth certificate from Eastern Kentucky, his claim to real country cred was doubtful. After all, Yoakam actually grew up in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, so how, the writer asked, were we to believe him when he said he’d eaten squirrel?

That line made me sit up and start ripping open the cardboard mailers of new releases next to my desk until I came to the gray and turquoise one with a sultry boy staring out from under his cowboy hat. I grew up as part of the hillbilly diaspora, too—child of people who’d had to leave the mountains they loved to live in a more northern city where there was work. Still bound to “home,” I’d eaten squirrel on some of our countless trips back to Corbin, Kentucky, in my childhood. I took that record home and played it at least a dozen times in two days before I sat down to write the full-page record review. Here’s a piece of what I wrote:

. . . along about my 12th listen I realized how thankful I am that I’m already living in Kentucky. Because if I happened to be anywhere else, even paradise, and I heard this album, I’d pack my bags in a minute to head straight back to the land of strip mines, polluted skies and broken dreams to search again for that mythical fantasy every hillbilly nurtures of a place called “home.” . . .

Yoakam sings with the heart of a man who not only knows about honky-tonks, but knows what drove the denizens there in the first place. It’s something a great deal more profound than plain romantic heartbreak. It’s a passion for place so searing it transcends the limits of time, distance and, most certainly, reality. When it tangles with the love of people or the need for a good life, it becomes an irreconcilable and unending hurt.

About a month after that review ran, I was on the road to Columbus with an assignment for a Sunday magazine cover story on this budding Kentucky-born star. Along with C-J photographer Pat McDonogh and his wife, Jeri (“I’m not going to miss that! ”), I was toting a crucial mechanical part that Dwight’s dad (then living outside of Louisville) had delivered to my door for a tour bus the band was having restored.

That show—the L.A. boy’s return to his stomping grounds—was in an old theater like the Georgia, but long before the days of restoration and updated sound systems. The crowd was small and the empty space echoed, which seemed to make Dwight and the band push it all the harder. But at one point he stopped to thank his mother and his aunts for being in the audience, for raising him right, and then he dedicated a song he’d written for them but hadn’t recorded yet: “Readin’, Rightin’, Rt. 23.” I tried to write down the words, but my hand was shaking. I may have cried.

Late the next morning, Pat set up an impromptu studio in Dwight’s room at the Red Roof Inn and started taking photos for the cover shot. Then we went with Dwight to meet his mom, Ruth Ann Rankey, at her sweet ranch house. Pat took more photos. I laid out for Dwight the fairly extensive parameters of what I hoped to get from our interviews for the story. I was planning to come to Austin in early summer and catch him at the annual Riverfest, opening for a lineup that included the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Los Lobos, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and the Fabulous Thunderbirds (in that order of prominence then). We’d have a day and a half to fit in a sit-down interview before I caught his show at Liberty Lunch. He seemed cautious but willing. We set a date for an initial phone interview.

I explained to Dwight that, while I was older, we seemed to have a lot in common, and not just in our mountain connections. I told him about the urgent need I’d felt in my early twenties to move, first to the Colorado Rockies, then to New Mexico, to get far, far away from home. It had seemed the only route to finding out who I really was. He grinned while I limned a quick outline of landing in the excitement and experiment of the counterculture. But after a while, I said, I realized I didn’t really belong in that world, and so I came back home. And then I realized I didn’t really belong in that world either. I said I felt like I always floated somewhere in between.

His eyes brightened and his voice came quick: “That’s it exactly! That’s how I feel. But you have to break the ties to be yourself, and then you see how much those ties meant to you, so you try to put them back. Only you can’t really do it. You can’t do either all the way. But that’s where the story is, right? That place in the middle, isn’t that where it’s art?”

It was the start of an on-and-off conversation that spanned the next four years.

Interviews with Dwight—at least mine—always occurred on Dwight Time and largely in Dwight Space. About two hours before that first phone interview, Dwight called to apologize and say his day was crazy. Could we reschedule? I said sure, we set a time a few days later, and then he proceeded to talk for at least another hour. He told me that his success was a combination of blind preparation and the right chance. He described the latter as, “You’re standing on the side of a sort of metaphysical railroad track with time being the train.” If you had your bags packed and you were fully ready, then an open window might go by, and you might be able to go through that window and on to the life you’d been preparing for. But there were a lot of people who never got that window, he said. And a lot of people weren’t ready to go through it when they did. He said he was one of the lucky ones. I thought he was one of the most prepared.

He encouraged me to talk to his folks for my story, especially his mother. She shared a black-and-white snapshot of toddler Dwight barely holding on to a guitar taller than he is. He pulled the guitar around after him everywhere until one day he fell on it and broke it. When Dwight turned nine, they didn’t have the money to buy him another guitar, but he begged so hard that his dad hocked a shotgun for one.

In high school, he had a band, Dwight and the Greasers, that played school assemblies and local dances. He also had a passion for theater that informed their shows. He wore a custom-made gold-sequined suit with a big hot-pink satin heart appliquéd on the back. The heart had a hidden pleat. As Dwight ended each show with a sizzling rendition of “Heartbreak Hotel,” he’d turn his back to the audience and as he murmured into the mic, “I get so lonely, baby, I get so lonely, I get so lonely I could die,” he’d hunch his shoulders and that pink heart would split right in two.

“I knew when I saw Elvis that I was going to be a performer,” he told me. “I have always had this need to be the guy with the guitar, poised on the edge, waiting for it to happen. Every kid goes through that need to imitate a rock & roll star. Then they move on to something else. But that need never left me.”

Long before Dwight launched a thoughtful movie career as a nuanced and unpredictable character actor, I witnessed his commitment to the theater of his work. In Austin, for about five hours spread over two days, I tagged along to two sets for the video of “Guitars, Cadillacs.” The two scenes I witnessed—one outside a funky old gas station, the other inside a garage—make up maybe twenty-five seconds of flash cuts in a three-minute vignette that also includes film of Dwight being interviewed at a radio station, playing on the sidewalk to a group of kids, performing with the band at Liberty Lunch, and signing a poster for the real-life cop who stopped to find out what was wrong as they filmed the band’s “broken down” Caddy being towed away by a farmer on a tractor. It was hot and dry those two days, and the director called for take after take after take. It wasn’t long before guys in the band began to moan each time there was a call for a new angle or a different twist. Dwight never bitched, just ran through it again and again, often suggesting a new twist of his own, until the director was satisfied. Maybe that commitment to detail is why the first single off Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc., “Honky Tonk Man,” spawned the first country video to play on MTV, followed shortly by “Guitars, Cadillacs” in frequent rotation. Maybe that’s part of why Yoakam won the Academy of Country Music’s Top New Male Vocalist award for that year and garnered two Grammy nominations.

It was 10:30 P.M. when the band took the stage at the Georgia Theatre. Plenty of rhinestones flashed on the boys, but the only ones on Dwight appeared on an appliquéd strip across the bottom of his jean jacket, depicting musical notes on a white background. Under the jacket was a pin-striped shirt—open collared, untucked. When he swiveled and turned, the shirttail covered his once damn-near-trademarked twitching butt. His cowboy hat was pale gray, and so were the locks spilling out from beneath. Even so, I expected I would hear a collective sigh from the women in the room, and a few good men, but the band was firing out an incredibly bombastic opening to “Please, Please Baby.” Dwight’s swivel in the vamps was a little softer than it once was, but by the time he’d followed up with a vibrant “Little Queenie,” then “Little Sister” backed by a huge wall of sound, punctuated by guitar slashes and drum hits like pistol shots, he had us in the thrall of the Hillbilly Cat.

“To me, the Hillbilly Cat is what country music is all about,” Dwight told me in 1986. “Hank Williams was a Hillbilly Cat. Johnny Cash with his ‘Man in Black’ was a Hillbilly Cat. And the biggest Hillbilly Cat of them all was Elvis. Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis—all those guys back in the fifties when rockabilly was hot, they were the Hillbilly Cats. They knew they were country. They knew the music they played was hot and they were cool. They dressed the part. They acted the part, and they played country music with an edge. And people loved it.”

From the get-go Yoakam has been conscious of his debt to the cats who went before, particularly those who may have faded from glory before getting full due. Two years into his career, in 1988, he teamed up with Buck Owens to release a duet of “Streets of Bakersfield.” It’s an indication of the influence of the Bakersfield sound, of which Owens is a major architect, that many assumed this Homer Joy song first recorded by Buck in 1973 was actually a Dwight original. The charming video that accompanied the single’s release launched a revival of Owens’s career.

Its performance in Athens lacked much of that original spark, but it seemed as if Dwight was only using it to launch a mini-lesson on the significance of the Bakersfield sound. It led into “Silver Wings” by the other seminal spirit behind that sound, Merle Haggard. Listening to Dwight sing Merle—“Mama Tried” and “Okie” followed—then later return to more of Buck’s songs, I was impressed that the fans around me, many of them not even born when Dwight first hit the charts, let alone when these guys were the bomb, were nevertheless getting the references. Not just getting them, but savoring the hipness of Buck and Merle. The young woman next to me whooped at the mention of Haggard’s name, then swayed hypnotically as Dwight slipped us slowly into the glistening sadness of “Silver Wings.” I wondered how much of her connection to this old song, to the older man who created it, was due to Dwight, to his working to share with his audience the music that shaped and made him? I was thinking quite a lot by the time he launched into Buck’s “Love’s Gonna Live Here Again.” And then it hit me—hard—that not only are these icons gone, but Dwight really is now the elder statesman. The éminence grise.

Dwight’s performance at Liberty Lunch in Austin that summer of 1986 was a far cry from the sparsely attended show I had seen in Columbus. The packed house of adoring punks, old hippies, hard rockers, and country music fans was in a near frenzy at a jacked-up, rocked-out version of Bill Monroe’s “Rocky Road Blues” that had guitarist/arranger/co-conspirator Pete Anderson flipping sweat from his hair like a drenched dog.

“Aww, it’s just old hillbilly stuff,” Yoakam said with a wicked grin. Then turning more serious: “You like that? Well then let’s see how much hillbilly you can stand.” And the band slowly slid into the aching melancholy of “Readin’, Rightin’, Rt. 23.” The crowd hushed.

Have you ever seen them put the kids in the car after work on Friday night?Pull up in a holler about 2A.M.—see a light still burning bright?Those mountain folks set up that late just to hold those little grandkids in their arms.And I’m proud to say that I’ve been blessed and touched by their sweet hillbilly charms.

Route 23 runs through the coalfields of Eastern Kentucky into the rust belt of Northern Ohio. Through the twentieth century, it was the route used to find jobs in the North whenever coal played out. The hillbillies were welcomed with the same sort of scorn most immigrants faced, although the stereotypes about Appalachia have proven to be unusually resistant to change. The joke in Ohio was then and still is this: “You know what they teach down in those Kentucky schools? Readin’, ’ritin’ and Route 23 north.” Dwight’s song is the counter to that scorn.

“We were taillight babies,” he said to me then, referring to the fact that his parents, like so many other Appalachians, would drive back “home” to the mountains every weekend off. And he and his brother, Ronnie, and sister, Kim, spent their summers in Betsy Layne, the small Kentucky mountain town where their grandparents lived. Many of the songs on his first albums tell stories that stem from the mountain culture he experienced as a kid.

“I was not ashamed nor made to be ashamed [of where I came from],” he told Dan Rather in a 2015 interview. The songs from that canon—“Rt. 23,” of course, but also “South of Cincinnati,” “Bury Me,” “Miner’s Prayer,” “Johnson’s Love,” “I Sang Dixie”—tell the complicated stories of mountain men and women, with an uncommon dignity. “If you’re a writer,” Dwight said to Rather, “you write about what you witness. And you can be a witness for other people.”

My story ran on August 3, 1986, but Dwight and I stayed in touch for the next couple of years, returning often to conversations about the importance of our unique backgrounds, or exploring the questions of how an artist can represent with both truth and artistry. Reader, I even had Dwight’s home phone number for a couple of years. And he had mine. I soon learned that the second I heard his distinct voice on the other end of the line, I should grab a big pad of paper and a pen. And that’s what I did on the afternoon of Saturday, December 16, 1989.

Two nights before, CBS had aired a much-touted episode of 48 Hours filmed in Floyd County, Kentucky, where Yoakam’s mother’s family is from. Dwight knew from his family that the film crew had spent time at a new science lab at the public school, interviewing proud students there, and he was told by the producers that it was a “cultural” piece on the region. So he agreed to have his music used and to be interviewed. When the episode, titled “Another America,” aired, however, it was pure poverty porn, a drive-by shooting of images and stories that furthered the ugly myths of a blighted region and degenerate people. It featured segments on cockfighting, a teenage wedding, spousal abuse, and health problems, as well as a negative take on the county’s severely underfunded school system.

“I’m in great anguish that my music and words were used,” Dwight told me right after saying hello. He wanted to know if I could run something in my music column the next weekend that could maybe reach the people of Eastern Kentucky and let them know how he felt. I said, of course, and he said he’d call me back in a day or two when he’d gathered his thoughts, and then he eloquently began to speak, while I wrote down his words as fast as I could.

“I thought what they did was very self-righteous, and it certainly was not even-handed. . . . We could do the same thing on poverty in New York and have people aghast. Or I could take you to any number of places here in Los Angeles and shock you. That would be real. But it wouldn’t be the truth if I made it look like that’s the way it is for everyone. . . . There is much more to Eastern Kentucky than poverty and despair. And it looked like they never shot a piece of footage that showed that other side of reality. They didn’t show anything of the progress or development in the region. But what’s even more important, they didn’t give an accurate portrayal of what it is to be poor and live there.”

Speaking of his mother and her family, all from Floyd County, he went on: “They were poor as far as money was concerned, but they made a life rich in other ways. And I didn’t see people like them in the 48 Hours show, although I know there are plenty of them there.”

In some scenes, the use of his music made him physically cringe. “I have tried in a lot of my music to give a sense of the beauty and the strength that comes from being in that part of the country,” he said. “But they laid my music over their images, and their images of Eastern Kentucky aren’t mine. I don’t mean to sound like a pious ass. Having your music misunderstood is a part of my profession and nothing new to me. Part of the deal is you create something and put it out there, and people interpret it as they will. . . . My problem is that they used my music to hurt the emotions of an entire region and people. They inaccurately portrayed it and caused emotional distress to people that I love. And I wouldn’t have had that happen for the world.”

I’d been folding clothes on an uneventful Saturday afternoon. Now I sat amid shirts and blouses that were fast wrinkling and looked at the words I’d scrawled across several pages. It seemed to me that the people of Eastern Kentucky should not have to wait a week to hear them. So I drove downtown, wrote my article, touched base with my editor in features, and filed the story with the news desk. The next day, Sunday, his words appeared on the Courier-Journal’s front page.

Not in the mountains, but of them. In the business of storytelling, but out to tell the truth. That place in the middle. The place to be heard.

July 16, 2017. It was after midnight when Dwight stepped to the mic and gently began “I Sang Dixie.” Such an extraordinary song. An aching eulogy for an otherwise invisible man; a reverent elegy for those like him, who lost the thread in the diaspora. The hillbillies, the Okies, the Dust Bowl children who moved too far, found no promised land, and so invented a perfect home they could only return to in their memories or in the bottle. On this night, however, in a contemporary Southern college town where the very word has so many conflicted meanings, I was anxious when the first mention of “Dixie” sparked some fist pumps and whoops. But Dwight stayed the course with the story, his delivery purposeful, firm. I realized he was laying his image over the crowd, reeling them into his vision, not theirs.

And then we were scorching again. “Honky Tonk Man,” “A Thousand Miles from Nowhere,” “Little Ways,” “Guitars, Cadillacs” with a whole lot of twitching going on. When he hit “Suspicious Minds,” his voice was raw, but the pistons were still firing. And the crowd? Well, yeah, the crowd was screaming.

And me? I wasn’t feeling so old after all. In fact, I felt like I could sit up all night, digging through papers looking for what it was Dwight said at the end of that article thirty-one years ago. Ah. Here it is:

Sure, it’s fashionable to like roots rock music right now, and sure, there’s a fashion element in the cowpunk trend, but what we do is go beyond that. What we play is real and fundamental, and I think it speaks to almost everyone at their heart.

So far the only real criticism we’ve gotten from the press is one writer who came to our show and said, “This is nothing but country music. This isn’t anything new.” Well, that’s right, buddy! Did I say this was nouveau art music? Where did I say this was jazz? All I’m claiming is that every time we go out on the stage we’re going to go out there and play hillbilly music.

And burn the house down.

“Some Dark Holler” by Dwight Yoakam is included on the Kentucky Music Issue CD.

Enjoy this essay? Subscribe to the Oxford American.