Real People Radio Stories

By Jeffrey A. Keith

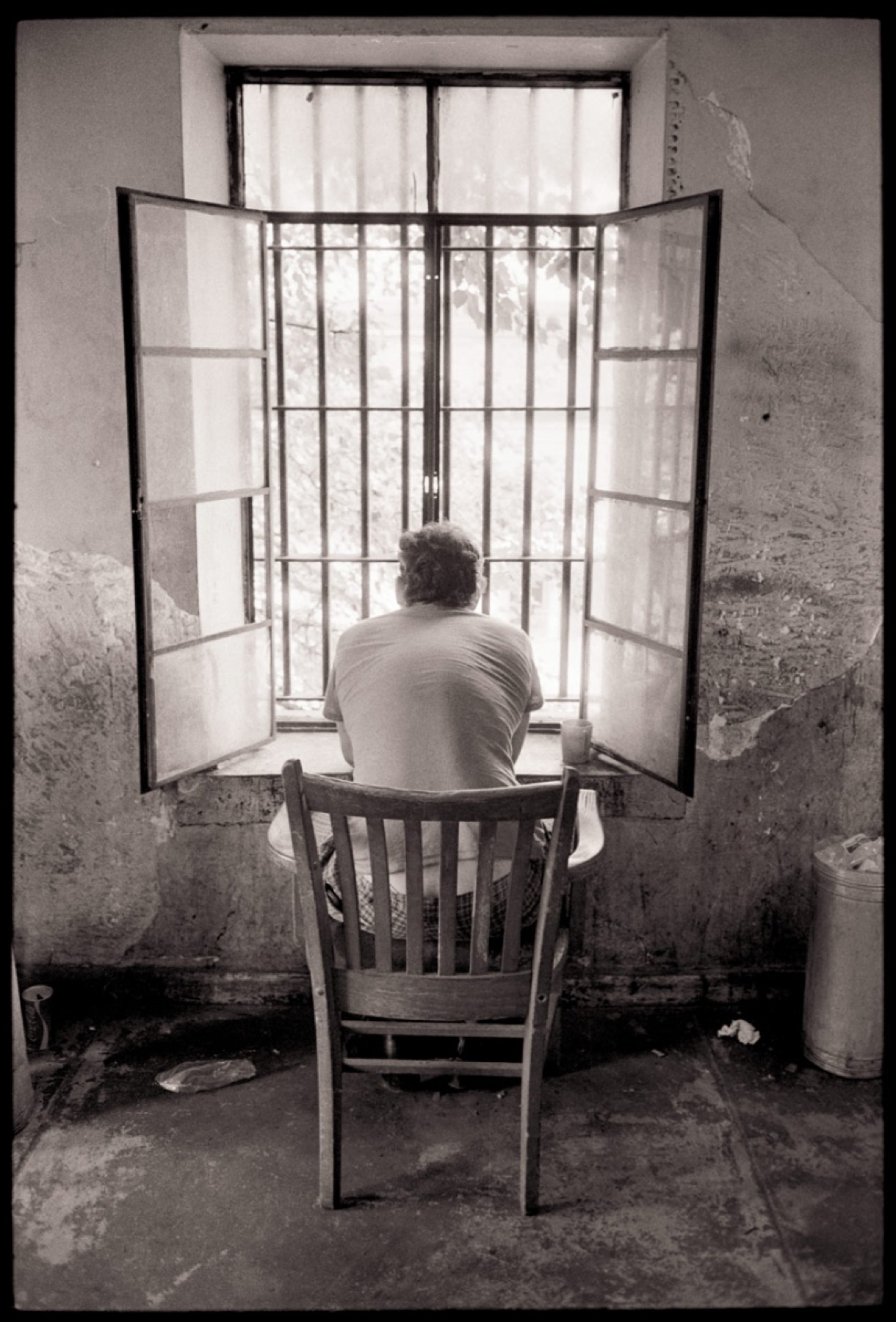

Jail Window, Laurel County, Kentucky. ©1975 Bob Hower / The Kentucky Documentary Photographic Project, kydocphoto.com

In an attempt to build support for his sweeping War on Poverty initiatives, President Lyndon B. Johnson famously visited rural Eastern Kentucky in spring 1964 and stamped an Appalachian face on the image of American destitution. In front of a platoon of reporters, LBJ crouched down on a front porch to talk with Tom Fletcher as a few of the unemployed man’s eight children looked on, bewildered. An iconic photograph captured that moment; it’s an object lesson in LBJ’s knack for political stagecraft as well as an example of how mountaineers have been used as props in national media narratives. The Fletchers had learned that LBJ was coming only a few hours earlier. “Wasn’t much we could do to fix up for him, but we were real pleased to have him,” Tom’s wife, Nora, told the New York Times. Before leaving, the president declared that people like the Fletchers would soon be spared the ravages of poverty.

Five years later and just down the road in Letcher County, a new federal program would approach the notion of uplift in a novel way. The Community Film Workshop of Appalachia, in Whitesburg, was founded to train Eastern Kentuckians for jobs in emergent media technologies, but the workshop was quickly transformed, by some of those same trainees, into a nonprofit, worker-run media collective dedicated to documenting life in the mountains and to empowering mountaineers to tell their own stories. Appalshop, as it was renamed, proceeded to screen its films at prestigious venues across the country and soon expanded its media output by founding a record label (June Appal Recordings), a theater troupe (Roadside Theater), and a literary magazine (Mountain Review). And in 1985, Appalshop launched a community radio station.

The station’s first transmission was of the revered union ballad singer Nimrod Workman offering a lyrical good-morning salute to “all of my people”—and WMMT 88.7 FM has been an inclusive and surprising notch on the dial ever since. It broadcasts at 15,000 watts from the center of Appalachia, beaming out from the highest-elevation transmitter in the state and serving the heart of coal country via an elaborate system of translators that bounce the signal up remote hollows, from Clay County, Kentucky, in the west to the coal counties of Southwest Virginia in the east, and bleeding over into the mountainous edges of West Virginia. WMMT once described itself as “the voice of the hillbilly nation,” and a sanitized version of that tagline serves today as the station’s official mission: “to be a 24-hour voice of mountain people’s music, culture, and social issues.”

While America has been slow to update its view of Appalachia—J. D. Vance’s bestselling Hillbilly Elegy stands as the latest example of an enormous canon that misidentifies Appalachian culture as broken and backward—WMMT challenges these notions for anyone who’ll listen. It broadcasts the preferences and meets the needs of a dynamic and diverse community that is far from its classic mischaracterization as static and homogenous. The result sounds like a joyous cultural refuge, one that defies mainstream radio conventions while eschewing the sedate professionalism of public radio. WMMT lives up to its other moniker: “Real People Radio.”

Matthew Carter, WMMT’s program director, has the word MARROWBONE tattooed across his toes in memorial to his home. “I lived and was raised in a little hollow named Laurel Branch on Marrowbone Creek in Pike County,” he said. “And it was always just a magical place to me.” Carter was twenty in 2005, the year the government used eminent domain to acquire—and destroy—the place called Marrowbone, making room for the expansion of U.S. Route 460.

His family’s forced relocation to the county seat of Pikeville was devastating, Carter says. But around that time, a friend he had made at a local punk rock show shared with him a June Appal recording of Nimrod Workman, who had grown up in neighboring Martin County nearly a century before. Carter remembers thinking, “If the hollows could speak at night, this is what it would sound like—the most haunting, chilling stuff ever.” Through the Appalshop internet forum Youth Bored, Carter found out about various concerts in the area and, before long, he was listening to WMMT. “I remember the first time I got it tuned in, and it came in crystal clear out in this backwoods, middle-of-nowhere part of Pike County where I grew up at,” Carter said. “I’m hearing this very abrasive metal on the radio. Honestly, it just blew me away. I was like, ‘I can’t believe they’re letting them do this.’”

Since 2015, I’ve been interviewing Appalshoppers to compile a vast oral history of the organization as it approaches its fiftieth anniversary. The people I’ve spoken with share a commitment to the importance of media-making in rural America. Carter’s story—one among many that I’ve heard over the past few years—is a testament to the transformative power an outlet like WMMT provides the people of an often-overlooked, largely rural region. He comes from a lineage of coal miners; he grew up in the mountains, but he didn’t realize what that meant until he discovered Appalshop and, through it, artists like Workman. “People value places differently,” Carter told me. “Our value isn’t in physical objects or anything like that, and it’s not even in our coal or the gas that’s here or any other fossil fuels. It has always been, and I think will always be, the people that have been here and continue to be here.”

Back in 2000, two popular DJs at WMMT began receiving fan mail from prison inmates. Eight Ball, an African-American coal miner from Harlan County, cohosted an r&b show, while Chick’n Man, a white strip miner from nearby Wise County, Virginia, DJ’d a rock & roll program. Listeners often called in requests, which the hosts obliged. Their respective shows were a hit, but the prison mail was an unexpected outgrowth of recent economic changes. With mining jobs dwindling at the end of the twentieth century, incarceration had become a leading growth industry in the coalfields. New prisons were installed on remote ridges and abandoned mountaintop-removal sites. They were filled with mostly out-of-state convicts who had only costly and limited means to contact their loved ones. But these prisoners had radios, and seven correctional facilities stood within the station’s listening radius.

Another WMMT personality, DJ Amelia, connected with the prisoner audience more directly. Amelia Kirby was raised on a mountain farm across the Kentucky state line in Scott County, Virginia. She attended Hampshire College, where her senior thesis explored social tensions between rural and urban people in central Appalachia’s prisons. When she moved back to the mountains, she started working at WMMT, where her father had been station manager. The Monday night hip-hop show she cohosted, “Holler to the Hood,” took on a new mission after she received a call one night. “There was a woman named Tamara X who had been incarcerated and was out, and she called into the show because she knew her brother was in the Red Onion State Prison in Pound, Virginia. She was like, ‘I know he listens to this show. Can I come on and say something to him? Can I just speak to him directly?’ I immediately responded, ‘Yes, you sure can!’ And I put her on the air, and she was like, ‘Hey, I just wanted to give you an update on where I’m at.’ And Tamara just spoke to him for two or three minutes, and then that turned on this massive light bulb. I realized, ‘Oh, we have this route for people to make a direct connection.’ Tamara kept calling back every week. She told other people. We started saying, ‘If you have loved ones who want to call in, here’s our phone number. We’re happy to take these calls.’”

From there, DJ Amelia devised a three-hour Christmas special as a means of connecting inmates to their loved ones during the holiday season. WMMT publicized it among the incarcerated listeners’ friends and families, and on the night of December 19, 2000, DJ Amelia, Chick’n Man, Eight Ball, and others put callers on the air to send holiday messages and song dedications straight through otherwise impenetrable prison walls. A girl sang “Silent Night” to her father, a grief-stricken woman cried as she told her husband she missed him, and WMMT’s loyal audience—both free and imprisoned—listened in.

DJ Amelia remembers that as she prepared to go live that night, “a guy called who was outraged that we were doing it. He was so angry that WMMT would do this, and just virulent about it.” The show proceeded, and it affected more than just the prisoners. “He called back literally that night, after the show, and was like, ‘Sorry. I didn’t really recognize what this meant.’ So we had very direct feedback that what we had imagined might be possible was, in fact, what was happening.”

In the wake of that success, DJ Amelia started a new weekly show, “Calls from Home,” that continues to serve as a bridge between prisoners and their friends and family. It is part of a three-hour block of Monday night programming targeted at incarcerated listeners. Elizabeth Sanders, a.k.a. DJ Izzy Lizzy, who is WMMT’s current station manager and now a host of “Calls from Home,” says the show fits well with the station’s mission: “For me, it’s pretty straightforward. These folks are locked up in our community, therefore they’re part of our community. And we’re a community radio station.” Incarcerated listeners continue to write fan mail to WMMT; much of it is simultaneously effusive and heart-rending. “Sometimes I feel like giving up. Sometimes I feel like I can’t win,” one letter reads. “But then on Monday I have DJ Rosa, DJ Izzy Lizzy, DJ Jules. And for three hours everything is OK.”

As a cornerstone personality at WMMT, both on and off the air, Amelia Kirby was in a sense keeping up a family tradition. While studying for a law degree at Yale in the sixties, her father, Rich, had returned to his ancestral home in Eastern Kentucky for work during the summers. In 1967, he spent the “summer of love” touring strip mines under the auspices of the Conservation Foundation. The next year, he worked as a researcher under the supervision of Harry M. Caudill, the Whitesburg attorney who had earned fame as the author of Night Comes to the Cumberlands, a history that accuses corporations of turning Appalachia into a resource colony. Kirby traveled from one county courthouse to another, compiling records to confirm that, just as Caudill had argued, absentee land and mineral rights ownership predominated throughout the coalfields.

A banjo player and a fiddler, Kirby also made time to learn string band music and balladry. He befriended Nimrod Workman, rallied striking miners with protest songs, organized a few music festivals, and eventually decided to give up on legal work altogether, moving to Appalachia permanently by the end of the 1960s. At Appalshop, Kirby met a group of like-minded young people who were determined to give mountaineers a chance to tell their own stories, and they began documenting the talents of community elders. Kirby recounts being present for a home recording of Workman singing “Black Lung Blues.” “You can hear coal trucks in the background on that one because there was no way to avoid that,” he explained. “We regretted that but later thought, Well, that sort of says a lot. That’s what this whole situation is.” (Media scholar Patricia Aufderheide has described Appalshop as an “unsentimental exercise in authenticity.”)

Though Rich Kirby would serve as WMMT’s station manager from 1991 to 2000—and continues to host an old-time music program called “Deep in Tradition”— he didn’t turn to Appalshop’s radio station until a trip to South Africa in the late 1980s sparked his interest. In Soweto, he remembers being “completely blown away” by music’s role in the anti-apartheid movement. “The utter importance of being able to tell your own story, to not have other people control your story for you—in so many ways that’s what music was in South Africa, because the conventional media outlets were totally controlled by the apartheid government,” he said. “I mentioned that at home, where I lived, we had a community radio station, and they were like, ‘Whoa! Wouldn’t that be wonderful?’ It was an impossible dream.” When he got back to Whitesburg, he approached Marty Newell, WMMT’s station manager at the time, to ask if it would be conceivable to play South African recordings on the radio in Southeastern Kentucky. Newell responded, “Well, you want to start on Tuesday?”

Highway 119 zigzags up the side of Pine Mountain, towering over Whitesburg, and crests the ridge at the site of Wiley’s Last Resort, an astonishing concentration of tacky lawn ornaments, log cabins, campsites, and a wooden stage. The brainchild of WMMT DJ Jim Webb, Wiley’s is an unconventional getaway set against the backdrop of a mammoth strip-mining operation to the south that is reducing portions of Black Mountain—the tallest peak in the state—to a jumble of barren gray plateaus.

An environmental activist, a descendent of Eastern Kentucky pioneers, and a poet with a penchant for puns, Webb blurs the line between his creative and everyday personas in tragicomic ways. He first adopted his on-air handle, Wiley Quixote, as the author of a satirical column in the Sandy New Era, a West Virginia newspaper that he helped found to spotlight local issues. Webb conceived of the name during a 1977 community meeting in Mingo County, West Virginia, where he was working as a literature professor. He and his fellow residents were organizing in the wake of a devastating flood in the Tug Fork Valley to which the federal and state responses had been, he said, “dismal.” During a discussion about immediate concerns, such as getting food into the county seat of Williamson, and structural issues, including the need to abolish the strip-mining that had exacerbated the flood’s damage, Webb remembers thinking, “We are tilting against windmills here.” Shortly thereafter, Wiley began publishing biting commentary about various politicians’ inability to manage flood relief, and eventually Wiley became the central character in Webb’s only credit as a playwright, Elmo’s Haven. The play is largely set in a bar that, like Webb’s long-running rock & roll variety radio show and his mountaintop retreat, bears an Appalachian-curio-cabinet aesthetic—one drawn from the legendary Red Robin Inn, a West Virginia watering hole where the barroom walls were decorated with mining equipment, musical instruments, and ephemera such as a photograph of a barefoot, twelve-toed moonshiner awaiting trial in a local courthouse. (Like Matthew Carter’s Marrowbone, the Red Robin Inn was obliterated to make room for a four-lane highway.)

Channeling the spirit of Wiley, Webb took his persona on the air soon after WMMT’s signal went live in 1985 and he’s still involved today. Now he’s a loyal member of the Whitesburg Rotary Club, a well-known local eccentric, and a man who believes deeply in the value of mountain-made media. “We have to keep things like WMMT and the Appalshop alive, no matter what,” he said. Webb takes some pride, too, in noting the radio station’s strengths. “WMMT thrives with personalities, with real people. ‘Real People Radio’ is not just a slogan or a little phrase. The whole point is that there is somebody who is real, somebody that you may even know. It’s a real person who talks like real people around here.” True to form, Webb concluded this thought with absurdist wordplay: “We’re serious radio. We’re not Sirius radio. And I’m serious.

“I feel like my radio show is an artistic and political statement each and every week, and I intend it to be, and I try for it to be,” he said. “And it’s one of those odd things that it’s a piece of art, as far as I’m concerned, but it just goes up and then it’s gone. And that’s one of the mysteries and majesties of radio—that if you didn’t hear it, it’s gone.”

“Shut Up in the Mines of Coal Creek” by Brett Ratliff is included on the Kentucky Music Issue CD.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.