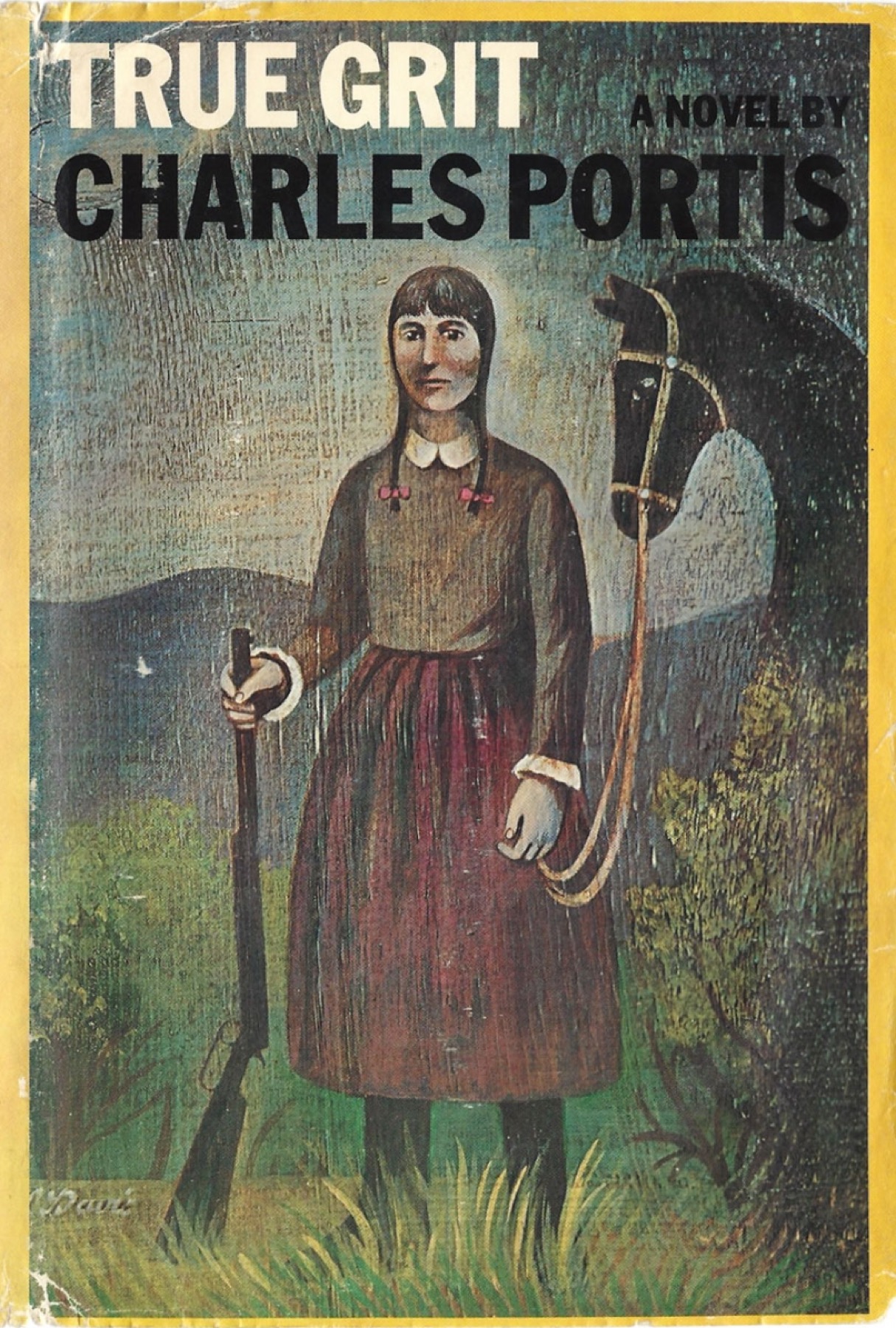

True Grit, first edition cover

THE MAN WITH THE KEYS

By Oxford American

WRITERS REFLECT ON CHARLES PORTIS’S LIFE AND LEGACY

The announcement of the death of Charles Portis elicited a social-media groundswell of mourning and appreciation from his fans. Comedian David Cross showed off his tattoo of the cover art on the first edition of Masters of Atlantis; Stephen King called Portis an “American original”; and readers from everywhere shared stories of True Grit’s or Norwood’s or The Dog of the South’s lasting effect on them, mostly citing the books’ repeated ability to produce unalloyed delight. Because he kept what I’ll call an unsocial media presence himself (he even remained email-less and cellphone-less till the end), the outpouring of affection from his fans was all about his words, which is how he always wanted it.

We at the Oxford American felt a special connection with him, being the home of the last two pieces he published and having honored him, our fellow Little Rockian, with an award for Lifetime Achievement in Southern Literature. We received our own outpouring from contributors and friends who wished to honor him with their own words.

—Jay Jennings, OA senior editor and editor of Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany

The question I am most often asked by reporters and students, in addition to “Why are you so angry?” is “Who are your favorite authors?” I have a few, not many. Reading is almost as hard as writing and I don’t always like much of what I read because I am a jasper of a man who lacks patience for most things. I can hardly finish a movie, even. Everything’s so bad. I’d sometimes just rather listen to seasonal birds.

But I have always loved the books of Charles Portis, that elusive Sasquatch of American Letters. His work was pressed upon me by friends and editors in hurried whispers, furtively. It’s a cult, or it would be, if the people who loved Portis had a gift for government, which they don’t. His books feel like what my own father’s books might have sounded like, if my father wrote books. I didn’t get them at first. I read The Dog of the South first and tried too hard. Like any old-timer’s wit, you have to listen for it or it’ll slide right by you and not even wave.

A few years ago, I had the honor of performing in Little Rock with some of my other heroes at the 50th anniversaries of his first two novels, Norwood and True Grit. I about died, I was so happy, and I held out hope that I might meet him, knowing I would not. I did meet his niece, and a man who said he ate lunch with him, once, and who seemed like he was drunk and lying. Portis remained obscure, even in his own town. I admired it. I am such a desperate harlot for promotion, that I bow to anyone who was immune to the fleeting assurances of fame. He was his very own John Selmer Dix, gone before you even knew he was there. If I write a funny novel one day, I’ll be plagiarizing Portis, you can put your money on it. What a mystery he remains! Memory eternal! Thank you, Mr. Portis! With wings as eagles!

—Harrison Scott Key

hinking hard about Charles Portis, whose work I greatly admire—the Portis tone, the Portis throwaway line, the Portis obsession with comic detail—I compare him with Gogol, because like Gogol, Portis is obsessed with rural strangeness and dumb officialdom and has no message. “Something is very wrong and all men are mild lunatics engaged in petty pursuits that seem to them very important, while an absurdly logical force keeps them at their futile jobs”—thus Nabokov writing about Gogol’s world, which is also Portis’s.

It is appropriate to mention these other writers, because it is clear in Portis’s writing that he was a tremendous reader, his books full of arcane lore. He was widely traveled in Europe and a passionate road-tripper in the USA—in one of his best short pieces he anatomizes cheap motels—and in True Grit he wrote an American masterpiece. He knew Mexico well, and used this knowledge in The Dog of the South and Gringos. He was much on my mind over the past three years, when I was driving around Mexico for my latest book, On the Plain of Snakes, in which he is quoted.

In the year I spent on my road trips for my book Deep South I met Portis in Little Rock. Anyone could see from his bearing that he’d been a Marine. We chatted a while. We talked about books; we talked about Mose Allison. I told him where I was going in Arkansas that week—El Dorado and Smackover—and he said, “Be careful.”

He was the real thing, but he was modest about it. An awestruck fan meeting him by chance in a Little Rock bar named the Faded Rose gushed at him, praising him as a great American writer. Portis shrugged saying, “I’m not even the best writer in this bar.”—Paul Theroux

“Dix puts William Shakespeare in the shithouse.” That was the line that did it. My buddy Skip Horack had turned me on to Portis. I started reading The Dog of the South with a mysterious sense that I had found the key to everything. That line confirmed it and sent me tumbling out of my chair. Soon I became your basic Portis degenerate, believing on some deranged level that the man had written his novels specifically for me. I can’t thank him enough for thinking of me so often throughout his career.

I wrote a television show called Lodge 49, which just got cancelled. It had no business being on the air in the first place so I can’t complain. It’s about a young man at loose ends who joins a secret society, the Ancient & Benevolent Order of the Lynx. Beer, softball, the secrets of alchemy. He finds a mentor and a new home. On one level, it was a very personal story about my family and life in Long Beach, California. Death, bankruptcy, foreclosure, loans, debt, dead end jobs, car trouble, more car trouble, and that feeling on Sunday when you’re driving down an empty boulevard in the fading light and suddenly a simple errand turns into an epic metaphysical bum ride. On another level, Lodge 49 is a love letter to all the writers who brought me joy and renewed my sense of mystery about this world. Portis is high on the list. When possible we made the loving allusions direct. In the pilot, the two main characters each get junk car fliers stuck in their windshield (that’s my 2004 Saturn Ion on the flier!). Masters of Atlantis was a touchstone, of course, with its “conspiracy from below” machinations and goofball reverence for Western esoterica, but really, the influence comes from every direction, in particular the generosity Portis shows to cranks, fools, dreamers, and people who don’t know how to climb the pyramid of American success. Bless them all, and bless Charles Portis, the man with the keys.

—Jim Gavin

I

t’s the first image I think of anytime I hear the name Portis. Some tan Haggar slacks, one leg crossed over the other, white socks, comfortable shoes. The top half of the figure in darkness, as if he were a spy being interviewed on a news magazine show.

When I was nineteen, I acted in a play Portis wrote called Delray’s New Moon at the Arkansas Rep. When the director, Cliff Baker, asked me to be in it, I had no idea who Portis was. When the run of the play was over, I still had no idea.

It’s not as though he didn’t speak. Like any tactful playwright, he spoke mostly through the director, but every now and then, a new line or a wry phrase would hurtle forward from the darkness, his legs now uncrossed, more of the figure visible. The thing about whatever line he said, in that singular Portis way, it was utterly bare and funny and belied all mystique. We would laugh, I would look to the back of the theater again, but he had retreated, only those tan slacks, one leg crossed over the other, visible again.

A few years later, I read True Grit. Then Dog of the South, Norwood, Masters of Atlantis, and Gringos. I had become a convert. To me, Portis was a messenger from another world. The textures were different. The characters were clearer and more fundamental than those I was used to reading. I began quoting hysterical lines and called things I loved “Pure nitro” as Reo Symes had taught me. I also started to recognize that the elements I loved most in the work of my comedic heroes of the time, like the Coen Brothers, Bob Odenkirk and David Cross from Mr. Show, Conan O’Brien, and on and on … those elements were completely embodied in a pure, single-malt essence that was Charles Portis. It was no surprise, then, to learn that all those people were outspoken fans of his work too. It turned out that Portis wasn’t just the seemingly taciturn old guy in the back of that theater, or the quasi-recluse who sometimes appeared at the bar of the Town Pump or Faded Rose. Portis had invented a form of comedy decades ago that no one had ever seen before, and he was the undiluted source of streams and tributaries that had been reaching me my whole life. His books were a collection of joyful … earnest … buffoons, and, my God, what a relief it was to read them.

As Henri Bergson taught us, the pleasure of characters who want the world to run like a clock is watching those characters learn that it never does. If you ask me what separates Portis from other great authors of his era, it’s that, as full of odd details as they are, as obsessed with the mechanics of things, specificity, and an oddly sad-sack masculinity, they are fundamentally vulnerable. Without saying an unkind word, he dismantled the idea of the heroic artist. Without mentioning them, he took the piss out of the Roths and the Mailers, the Updikes and the Bellows. It’s no wonder, then, that his genius was often overlooked.

Whether or not Portis suffered fools in life is worthy of debate, but in his work he did nothing so much as hug the fools and put them on display. He showed us what fools we are, what a fool he was, and that no matter how seriously we take our journeys across the country, or south of the border, we’re all resigned to a foolish fate. It’s hard to read any of Portis’s writing and believe he was a misanthrope. I believe the contrary, that he was wise enough to understand the absurdity of our fate, and as another comedic genius, Charlie Chaplin said, he took that pain out and played with it.

A few years ago, my friend (and collaborator on adapting Dog of the South into a screenplay) Jay Jennings, and Mr. Portis’s brother Jon offered me the opportunity to meet Mr. Portis again. We went to see him and I quietly handed over my first edition of Dog for him to autograph. He did, and I stared, silent and dumb, at the autograph more than at him, as if I might go blind from looking at the sun for too long. I should’ve loosened up. After all, if there’s one overwhelming message of his work, that seems to be it.

Of all the models and makes of humans, I’ve always admired this sort of human the most, these diffident, comic Buddhas who float along the meniscus of the water, maybe levitating, or maybe just unperturbed. It doesn’t matter which. As Portis taught us, they are the same thing.

Sometimes it doesn’t matter if you meet your heroes, because whichever way you look at them, at least half is still shrouded in darkness. That’s how I’ll always remember him. Tan slacks. Quiet. Watching. An occasional giggle to himself in the darkness. Making up new lines and stories. Pure nitro.

—Graham Gordy

As elusive in person as Sydney Hen, renegade Master of Gnomonism, Charles Portis was a brilliant writer and a comic genius, the equal of Mark Twain. I have read his novels countless times and they never stale. His stories travelled over the American entrepreneurial mindscape, its optimism, bathos, and near surreality. He was a virtuoso of the American idiom: of the go-getter’s lingo and the festivity of Southern speech. His people tended toward big ideas and car trouble, and he, himself, was an adept in the mysteries of the internal-combustion engine. When he died, he left behind an unforgettable cast of characters—boosters, sharp operators, plain speakers, windbags, zealots, righteous avengers, and dupes. Wherever he is now, it is pretty certain that he has in his pocket the keys to the universe and a ’52 Studebaker pickup.

—Katherine A. Powers

Forty years after Norwood Pratt traveled from Ralph, Texas, to New York City in a stolen car to collect a debt of $70, I arrived in New York from Texas in an aging, oil-burning Chevrolet Beauville van about which Charles Portis would surely have had opinions. Like Mattie Ross and Ray Midge after him, Norwood is out to settle a score; perhaps on some level I was too. Nonetheless I soon found myself intermittently employed as one of “those copy desk drifters,” as Portis referred to them in a 2001 interview with Roy Reed. I had been turned on to Portis several years earlier and now, in the inevitable moments when the city paled against its promise, I couldn’t help but see it through Norwood’s eyes: a suspect place where a man must eat “corrugated” French fries and drink coffee out of a “paper cup with handles.” (Pratt did love his Automat.) Though fleeting, Norwood’s episodic adventure is not without its good times: an aspiring country singer who prefers “modern love numbers” to folk songs, Norwood makes the acquaintance of a beatnik girl who takes him to the Cloisters once, the Staten Island ferry twice, and in the evening, clips his nails as she reads aloud from The Prophet.

Norwood never gets his $70, but I believe Charles Portis reaped what was owed him for his own years as a reporter in New York and then some. “Usually my books are like those Slim Whitman records you see on TV—‘not available in any store,’” Portis said in 1984, when reached for a Talk of the Town story. “But all you can do, you know, is write the stuff and put it out where people can get at it.” Dog of the South had recently fallen out of print, and the Madison Avenue Bookshop had purchased every remaining copy (183 at the time), a correct and understood impulse. For this is a common affliction of Portis people—we buy up every single dog-eared copy of his novels that comes our way and spread our contagion to everyone in our midst.

—Rebecca Bengal

I am sad that Charles Portis, whom I knew as Buddy, has died. But let us recall what Rita Lee says about her maybe-ex-boyfriend in Norwood: “He would favor Rory Calhoun a lot if his neck was filled out more.”

Portis, of course, did not resemble Rory Calhoun. Nor did Portis’s neck appear to be skinny. That is not what I am getting at.

What I am getting at is this: Every time I pick up a book by Portis, something pops out at me immediately. Something that is really funny and just like what people say sometimes.

Pops out again. A friend of Portis’s, Robert Dumont, once told me, “Nobody re-reads better than Charles Portis. In fact, nobody re-re-reads better than Portis.”

And now he isn’t gone, not hardly. I don’t know what convictions Portis may have had about the afterlife, but here is a conversation, from The Dog of the South, among narrator Ray Midge and Dr. Symes’s mother and her friend Melba:

“What about Heaven and Hell. Do you believe those places exist?”

“That’s a hard one.”

“Not for me. How about you Melba?”

“I would call it an easy one.”

“Well, I don’t know. I wouldn’t be surprised either way. I try not to think about it. It’s just so odd to think that people are walking around in Heaven and Hell.”

“Yes, but it’s odd to find ourselves walking around here too, isn’t it?”

“That’s true, Mrs. Symes.”

I don't know how many times I have read that passage. This time, “I wouldn't be surprised either way” is the best part, maybe. Especially if you know Ray Midge.

Portis’s stuff keeps getting better. And it doesn’t matter whether anybody knows what Rory Calhoun looked like anymore.

—Roy Blount Jr.

Contributors

Rebecca Bengal, presently living motel life in the lower reaches of Virginia, writes fiction and nonfiction. A new short story accompanies Justine Kurland’s monograph Girl Pictures, forthcoming from Aperture this spring.

Roy Blount Jr. is the author of twenty-four books. His latest is Save Room for Pie: Food, Songs, and Chewy Ruminations.

Jim Gavin is the creator of the TV series Lodge 49, and the author of the short story collection Middle Men.

Graham Gordy’s short story “Who Carried You” was featured in the Oxford American Summer 2019 issue. He was a writer and producer of and actor in the recent independent film Antiquities, writer for the Sundance series Rectify, co-creator and executive producer of the Cinemax drama Quarry, and a writer and consulting producer for the third season of True Detective..

Harrison Scott Key is the author of two books, Congratulations, Who Are You Again? and The World's Largest Man, winner of the Thurber Prize for American Humor.

Katherine A. Powers reviews books widely and received the National Book Critics Circle Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. She is the editor of Suitable Accommodations: An Autobiographical Story of Family Life: The Letters of J. F. Powers, 1942 – 1963.

Paul Theroux is the author of many highly acclaimed works of fiction and nonfiction, including The Great Railway Bazaar, The Mosquito Coast, Riding the Iron Rooster, Mr. Bones: Twenty Stories, and Deep South: Four Seasons on Back Roads.

Read more from and about Charles Portis here.