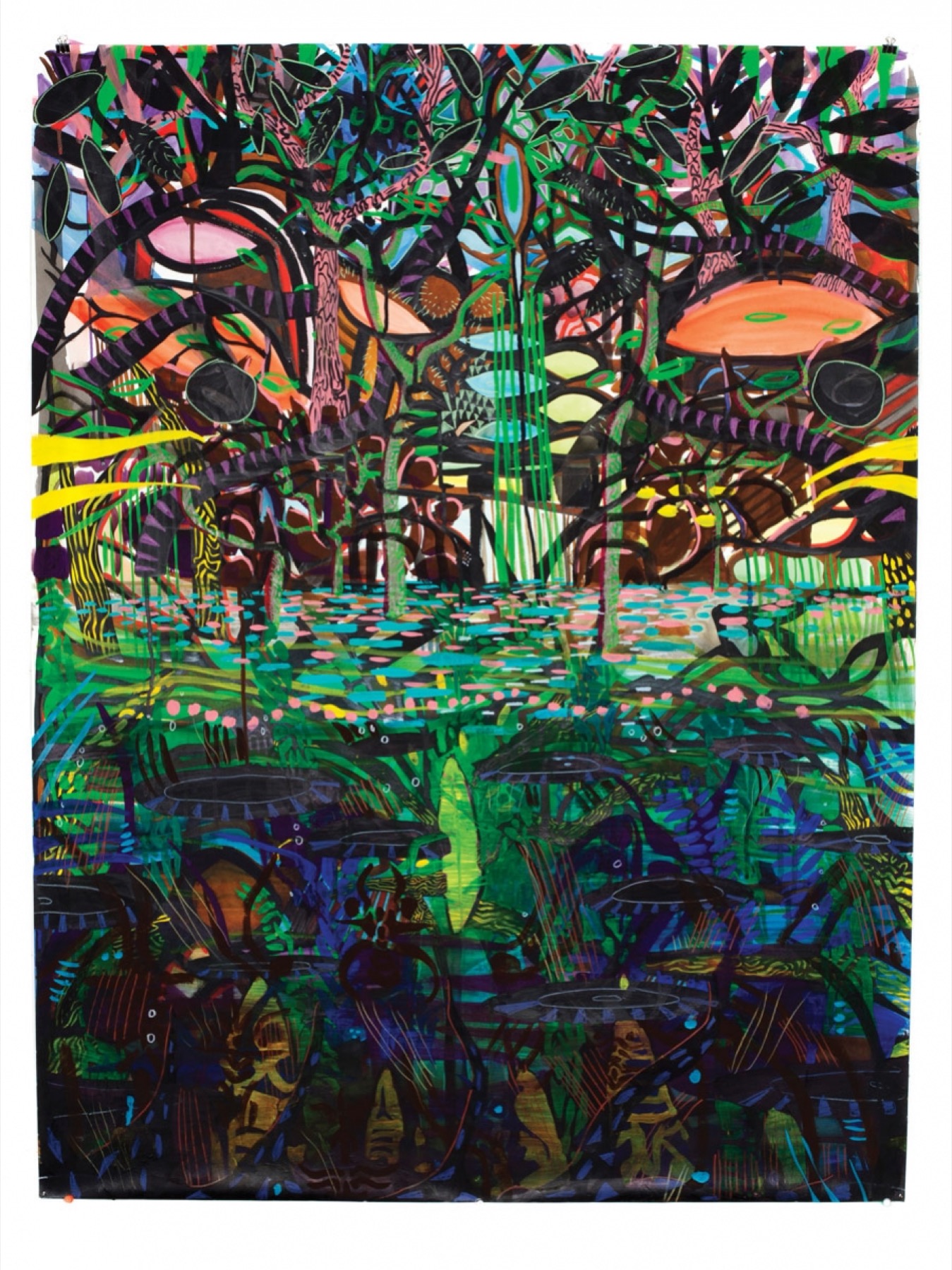

“Madam, In Eden, I’m Adam” (2015), by Jules Buck Jones. © The artist. Watercolor and mixed media on paper. Courtesy Conduit Gallery, Dallas

Hunger for the Water

By Leslie Pariseau

At the fraying tips of Southern Louisiana, it can be difficult to tell just how close the water is until you’re face to face with it. Standing on the dock out back of the Cecil Lapeyrouse Grocery in Chauvin, a fishing town seventy miles south of New Orleans, Melissa Martin points across the bayou to a marsh where several pale, wizened tree trunks reach up from the earth as if in praise or in penance. Small and lithe with long, wavy hair the color of heron feathers, Martin recounts standing around with one of the old-timers who stops in for coffee at the 106-year-old store each morning. He told her that a century ago, sugarcane fields stretched across that now soggy expanse as far as the eye could see. But today, the land has been eroded, most of the sugarcane industry has picked up and moved north, and what remains are sunburnt grasses and salt-ravaged cypress skeletons, waiting to be swallowed by the ever-encroaching water.

Over the course of the afternoon, as she drives down Highway 56 (aka Little Caillou Road) and back, Martin, chef and owner of Mosquito Supper Club in New Orleans, points out a dozen more horizons where land or homes, a dock or a bait shop used to be. Some of them have been taken by the organic shuffling of generations, others by storms and flooding; so much has been swallowed by the oil industry’s diversion of the Mississippi or the hungry, rushing Gulf of Mexico. Martin says that Bayou Petit Caillou, which bobs with shrimp trawlers and oyster luggers, and runs parallel to Highway 56 past her hometown of Chauvin, is arguably the country’s longest Main Street—a geographical point of reference that carries life in and out by the tides of the moon. These islets and peninsulas, and all the water that runs through and over them, are deeply Cajun territory. And Martin, though she’s lived in New Orleans for almost twenty-three years, cannot identify anywhere else as home. Her life’s work and her recently published cookbook Mosquito Supper Club: Cajun Recipes from a Disappearing Bayou, revolve around the food born of these waters, the unwritten recipes that have passed through its kitchens and greased its Magnalite pots. It’s a tradition of Cajun cooking that she sees as vital to document—particularly at this moment when this ragged fringe of America has already, by many, been chalked up to lost.

Later, Martin parks at a building made up of a series of brutalist-style boxes that stands out amid the highway’s smattering of clapboard houses on stilts and the tropical-hued vacation homes just south at Coco Marina. Out front, a sign reads LOUISIANA UNIVERSITIES MARINE CONSORTIUM. A center for the study of Louisiana’s coastal waterways and marine systems, LUMCON’s sprawling campus straddles dry land and the murky, grassy coast that one day will likely recede into salty, muddy seashore. Martin climbs eight flights of stairs to the Consortium’s overlook, where a class of college students from Minnesota gazes out onto the horizon. From here, it’s undeniable how nearby the water is. It percolates beneath everything. Up here, the marsh-scape appears like a de Kooning; swaths of green and blue, weaving in and out, permeating each other so deeply that it’s difficult to tell which came first—each constantly shifting, cradling, and defying the other in a never-ending tangle of wills.

Blackened fish. Bayou buffalo wings. Bourbon chicken. Since the proliferation of Cajun-style-everything beginning in the 1980s with chef Paul Prudhomme’s national celebrity and the co-opting of the word by corporate fast food, the American notion of Cajun food has been disassociated from its actual significance. In fact, the tradition was born of the French-speaking Acadian people driven from their homes some 3,600 miles north in Canada’s maritime provinces, beginning in 1755. Called Le Grand Dérangement, this expulsion took place during America’s Seven Years’ War, and was the consequence of the Acadians’ refusal to bend a knee to the British crown. Those who survived the trek south settled across the plains, bayous, swamps, and marshes of Southern Louisiana. Martin traces her lineage to these exiled Acadian people (as well as Corsican missionaries) who carried their love of salt pork, fishing, and hunting across the Mason-Dixon and down to the cypress- and live-oak-strewn fingers of what is now called Terrebonne Parish. Martin’s family is of the tradition of marine Cajuns—those families who have made their living and homes with the rhythm of the tides—which is culinarily distinct from those Acadians who settled northwest of New Orleans in and around Lafayette, which is considered the heart of Cajun country. There, pork, tasso, boudin, and rabbit are the centerpieces of the table. Unless, of course, it’s crawfish season.

At her restaurant, Mosquito Supper Club, and in her cookbook of the same name, Martin sets out to record the foods and recipes that cannot be found on New Orleans’s restaurant menus or at a Popeyes drive-thru (shrimp boulettes, thistle salad, muscadine compote) and those that have become so synonymous with Louisiana cooking (crawfish étouffée, seven kinds of gumbo, oyster soup) that their points of origin bear reminding. In preparation for writing her cookbook, she spent months standing with her mother and aunts over their stoves, attempting to translate the alchemy of formulas that had never been set down for posterity. Each recipe and chapter is enfolded with stories, practical advice, and the lore of the bayous. Martin describes the wonder at watching a molting crab walk backward out of its shell, the pleasure of sucking a crawfish head, and the old Chinese and Filipino tradition of drying shrimp in the hot Gulf sun. She’s intent on this documentation not only because it’s been so misunderstood and misconstrued over the last several decades, but because it’s possible it all might soon be lost.

“Cajun is something subtle,” says Martin, focused on the road ahead. She points out a dozen cows balanced on a finger of land elevated above the inlets. In her books she says that the word “Cajun,” along with “Creole,” has taken on new meanings and is an ever-evolving term. “It’s often [exaggerated] in the media and in the mainstream as something to capitalize on. And this place is a true example of being capitalized on. Our natural resources have been capitalized on to the point of destruction.” At its most reductive, “Cajun” commodifies the idea of the bounty reaped from the bayou; at its richest, the word encompasses the rhythms and rituals of life that have shaped a culture.

She parks the car at Cocodrie, the terminating point of Highway 56, a tiny, unincorporated village on the Gulf where her mother was born, and points out the great irony of the bayou. On one side of the road is her cousin Roxanne’s shrimp dock, where a boat has anchored to unload a shrimp catch after a trip out to the Gulf. A glossy chocolate-colored dog runs around frantically chasing salt spray, while a sun-burnished fisherman in overalls lifts a Budweiser to his lips. A porpoise fin crests fifty yards out, and a couple of pelicans alight on dock posts. On the other side of the road is a crude-oil fuel dock. It appears empty of human life, looming against the blue horizon.

“It seems like such a paradox,” says Martin. “It’s one of those things that I don’t think most of the country quite understands—the proximity of these businesses. They can’t, they can’t possibly.” Like everyone in Martin’s family, her father has always been a fisherman. Depending on the season, he caught oysters, shrimp, crawfish, and more. Eventually, he went to work for the oil industry, and later became an adventure guide for the politicians and oil industry executives who came down on weekends to fish—another irony that is not lost upon Martin. It’s a common story here, this cycling between jobs that seem to be diametrically opposed to one another, and yet literally occupy the same waters.

Later that afternoon, sitting in the kitchen she grew up in, talking with her mother Maxine, who has a dark, sparkling gaze and salt-and-pepper hair done up in a tidy bun, and her father Chucky, from whom Martin clearly gets her translucent blue eyes, she asks what they think about when they think about the water. Maxine stops and reaches for a memory. “I think about my daddy walking waist-high, carrying me to a boat because the water was coming up because of a storm. I remember one time escaping in a car because my daddy wouldn’t leave, and the water was even with the car.” Martin nods. She knows this story. “I had this big purple poodle that Daddy gave me,” says Maxine. Martin laughs and slaps the table. It’s a new detail she’s not heard before, but one she knows she’ll quickly assimilate—a new bit of color to embroider seamlessly into her family’s mythology.

Being in Chauvin with Martin is to be flooded with mythology. Down the bayou, just after the Boudreaux Canal Bridge, lies a brigade of white grave markers studding a mound of earth; a plaque out front posits that the Picou Cemetery lies atop a Native-constructed mound from around AD 1000, and that the oak tree at one corner marks the grave of Touh-la-bayne of the Biloxi Nation, who was thought to own the property two centuries ago. There are yarns about the rougarou, an imaginary wolf-bear-like creature that’s said to prowl the swamps and prey on local children. Martin’s parents were told that the rougarou haunted a particularly creepy intersection halfway between Chauvin and Cocodrie. Then there are the tales that are so deeply entwined in Martin’s family’s history that they’ve become origin stories all their own.

After fueling up her VW Golf with diesel and getting back on 56, Martin drives for a few moments before pulling over to one side of the road. Out her window is a small rectangle of land, cordoned off by white rails. In the middle is a white stone grave marker that reads HENRY NEAL’S WIFE AND CHILDREN PERISH HERE IN 1909 STORM. Martin recounts the story of her great-grandfather Henry Neal who in September of 1909 was out oystering in California Bay when a storm swept across the bayou. Unable to get home in time, he rode out the weather, and returned home to find that the storm had taken his wife and five children’s lives. Later, he married again. “My grandmother wouldn’t have been born if this horrific tragedy hadn’t happened, if the water hadn’t taken all of their lives,” says Martin, wondering at the cosmic irony of life, death, and the water that cascades about them both.

Another irony: Her mother didn’t learn how to swim until she was an adult. Maxine says she and her sister Christine, the youngest girls of nine siblings, were rarely on the water; rather, they were charged with domestic duties, which she translated into her own life’s work, raising up six children—Martin is the third—and holding down the homestead (Martin’s book is dedicated to her mother and her full-time commitment to bringing them up).

“My mom and dad met because of oysters,” writes Martin in her book. “My dad remembers seeing my mom on her dad’s dock while his parents bought oysters from her father. He was probably only eight years old, but he was smitten.” In the same kitchen they’ve spent decades in, the same kitchen they’ve rebuilt after each storm, the same kitchen they fed six children from, Maxine and Chucky recount this story, Chucky glowing at his enduring luck. Maxine shakes her head at him, smiling.

“For being raised on the water, I have a weird relationship with it,” says Maxine. “When we’d go to the beach and [the kids would go out] into the water, I [would] have to leave,” she says. Her anxiety that they might drown or be swept away had been overpowering. She suspects it has to do with her mother, who worked on an oyster boat, cleaning, cooking, fishing—back-breaking work; once her mother stopped working, she had no desire to ever step off dry land again. It’s worth wondering how much of Maxine’s anxiety is connected to her childhood memories of storms—the waist-deep water and the feeling that she too might have been carried away. Martin seems to have inherited an equal measure of attraction toward domestic duty and a fierce hunger for the water.

“Humid Future” (2018), by Jules Buck Jones. Watercolor and mixed media on paper. © The artist. Courtesy Conduit Gallery, Dallas

“Humid Future” (2018), by Jules Buck Jones. Watercolor and mixed media on paper. © The artist. Courtesy Conduit Gallery, Dallas

In New Orleans, Martin spends most of her time in the pale yellow cottage Uptown on Dryades Street, where Mosquito Supper Club resides. Before starting the club as a pop-up and migrating it here, she worked with the Crescent City Farmer’s Market, cooked for emergency workers during Katrina, and eventually made her way out to Napa, where she spent a harvest and another summer learning to cook. Now, along with her sous chef, prep cook, and porter, she cooks at a six-burner stove mostly in cast-iron pots and pans, which, full of bisque or sweet-potato biscuits or gumbo, often get hauled out to the restaurant’s communal tables. For thirty-six people, Thursday to Sunday, Martin presides over the kitchen and the dining room, explaining the food she grew up eating, all sourced from the places and people who remain the lifeblood of the bayou food system.

In this context, she’s an interesting presence. Sometimes wearing a flowing skirt, other times suited up in Carhartt overalls and boots, she defies the stereotype of domestic warmth that might be expected from someone in the business of feeding people. Rather, she is serious, matter-of-fact, eager to relay a message that is equal parts intellectual and political, and very, very urgent. Yes, she is feeding you, but it is imperative for you to know why she’s here, and by extension why you’re here. It’s necessary that you know who is responsible for the tradition of Cajun food and the fact that it’s so much more than a term referring to a level of spice or char. She wants you to know about the filé made from sassafras by the elders of a local Houma tribe that thickens the gumbo on your table; about the Higgins family from Lafitte whose meticulously sourced crabs are the only ones that will cross her tables; why the damming of the Mississippi and the proliferation of the oil industry, combined with Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, ravaged the oyster beds and the delicate economy of the coast. “It’s imperative that the small fishing villages that push out so much seafood, tradition, and culture be recognized and remembered before time and tides take their toll,” she writes.

Yes, Martin is keen to feed people, but she is also fixated upon the translation of a culture, a place, and a people whose story is difficult to fully articulate if you only think about it in terms of individual courses and ingredients. Darlene Wolnik, training and technical assistance director for the national Farmers Market Coalition, who worked with Martin early on, says she’s unique among the city’s chefs because she’s “focused inwardly on her craft, testing herself against the matriarchs of her own family, and against the standards of her ‘water Cajun’ culture rather than winning in the public arena of the New Orleans restaurant scene.” In a city where very few truly Cajun experiences are present, Martin’s work is an anomaly, and it requires constant renewal; she travels home often to fish with her dad, stand over the stove with her mom. Like the bayous, the marshes, and the life that swims about them, interconnection is vital for survival. You cannot shift one without the other feeling an ebb or flow.

Lately, Martin has been contemplating how much longer she can sustain the Supper Club. (When COVID-19 began to disrupt the city’s hospitality industry service, she shut the restaurant down to cook for healthcare workers, later opening for take-out, then for dine-in at half-capacity; her book tour and launch party were effectively canceled.) After each service, she feels exhausted, wondering how she will ever pay herself a living wage. “I cooked my way through heartbreak,” she says of her divorce over three years ago. She also cooked to provide stability while raising her son Lucien in New Orleans. Then she cooked to illuminate the hidden corners of her people’s culture. Now, her son is mostly raised, she is in love again, and she has written a book that will stand as a record for decades to come. And yet, Mosquito Supper Club is so entwined with her identity and her mission that it’s difficult to imagine what would come next.

At the end of the afternoon, Martin stops into a Marty J’s, a Chevron gas station with a sandwich counter where the staff will clean and fry your fish if you’ve just come in off the water, and orders a shrimp po’boy, dressed. With the scent of freshly battered and fried seafood filling the car, she pulls down the only street she’s ever called home—whose residents are mostly her aunts, uncles, and cousins—and recounts a recent morning arriving in Chauvin and walking into the one-story brick home.

Her mom had just finished making pancakes and was putting on a pot of beans for dinner when Martin’s aunt Earline came in asking if she could take some fish from the freezer. Later, Earline returned with a Crock-Pot full of wild ducks her husband had just hunted and Martin’s dad walked in with a fresh catch of fish. Chucky settled in with the ducks, while Martin’s other aunts came over to divide up his catch for their own suppers. Soon after, Martin’s aunt Christine showed up with a bucket of crabs because Chucky had mentioned a craving while out fishing with her husband Gordon.

“It’s a constant rotation of feeding each other and talking about food,” says Martin. “My dad fishes almost every day, and that’s how they feed themselves. He doesn’t fish commercially anymore, but he’s still feeding a family.” What is novelty for some, she’s saying, is essential to these people who have never known anything else. Here, on the bayou, the tides are the clock by which life is lived, and when the tide shifts, so does the life that depends upon it.

Boiled Shrimp

Excerpted from Mosquito Supper Club by Melissa Martin (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2020.

The secret to boiling any seafood is a flavorful stock. Your stock should taste good before you add the shrimp. My mom claims that adding butter to the stock makes the cooked shrimp easier to peel—and I would venture to say it adds some flavor, too.

When you serve them with crackers, seafood dip, corn, and potatoes, it takes just a couple dozen shrimp to fill you up. If it’s summer, serve some watermelon topped with a sprinkle of sea salt for dessert. Any shrimp you have left over can be used in another meal—maybe a shrimp omelet for breakfast or shrimp dip for a snack. You can also peel and freeze shrimp, then use them as a binder in crab cakes. Try not to waste a single shrimp.

Serves 6

1½ bunches celery (about 11 stalks), cut into 4-inch (10 cm) pieces

6 pounds (2.7 kg) yellow onions, quartered

12 lemons (3 pounds/1.35 kg), halved

1 tablespoon cayenne pepper, plus more as needed

1 tablespoon whole black peppercorns

5 pounds (2.3 kg) medium head-on shrimp

½ pound (2 sticks/225 g) unsalted butter

1 to 1½ cups (240 to 360 g) kosher salt

12 ounces (340 g) small red potatoes (about 6), scrubbed

6 ears corn, husked

Crackers, for serving

Maria’s Seafood Dip, for serving

Fill a heavy-bottomed 4-gallon (15 L) stockpot halfway with water. Add the celery, onions, lemons, cayenne, and peppercorns to the pot. Bring the water to a boil over high heat, then reduce the heat to low and simmer until the vegetables are soft, about 1 hour. Taste the stock; it should have a subtle bright vegetable flavor and taste clean, with hints of onion and celery. If it’s nicely flavorful, you’re ready to boil the shrimp; if not, simmer for 30 to 45 minutes more, then taste again.

When the stock is ready, raise the heat to high and return it to a boil.

Rinse the shrimp briefly under cold running water and drain (don’t overwash them—you don’t want to rinse away all their flavor). Add the shrimp to the boiling stock and use a spoon to submerge them so they can release all their flavor. Let the liquid return to a boil, then boil the shrimp for 4 minutes.

Add the butter to the pot, stir and cook for 2 minutes more, then pluck a shrimp out of the stock and check for doneness. The shrimp should be bright pink and firm; if needed, cook for up to 2 minutes more, then turn off the heat. (They can get mushy quickly, so don’t overcook them—from the time the stock returns to a boil after you add the shrimp, the total cook time should be no more than 8 minutes.)

Stir ½ cup (120 g) of the salt into the stock and let the shrimp soak for about 6 minutes. Taste the shrimp for flavor: your shrimp are done when they taste buttery and sweet, with hints of cayenne and the perfect amount of salt. At this point, you may need to add more cayenne or salt. Add cayenne to taste. Add another ¼ cup (60 g) of the salt and let the shrimp soak for 2 to 3 minutes more; repeat as needed. The amount of salt you use is relative: some folks want only a little, and some want a bit more. Finding the perfect balance is a matter of taste, but if your shrimp taste bland, they probably need a little more salt and a longer soaking time.

When you’re happy with their flavor, use a strainer to transfer the shrimp to a large bowl, or set a colander over a large bowl and drain the shrimp in the colander, then transfer them to a large bowl (reserve the stock).

Return the stock to the stove and bring it back to a boil. Add the potatoes and boil for 6 minutes, then add the corn to the pot and boil the vegetables together for 4 minutes more, until the potatoes are tender. Strain the potatoes and corn and discard the stock. Transfer the potatoes and corn to a bowl.

Thoroughly prepare to feast: Cover a table with newspaper. Have your crackers out and ready to eat and small bowls of seafood dip for each person. Have plenty of paper towels or napkins ready to go. (Once you get your hands dirty peeling, you won’t want to be grabbing supplies.) Pour the shrimp, corn, and potatoes right out onto the center of the table and enjoy.

Maria’s Seafood Dip

Makes 3 cups (720 ml)

2 cups (480 ml) mayonnaise

1 cup (240 ml) ketchup

½ yellow onion, finely diced

1 teaspoon yellow mustard

1 teaspoon hot sauce, preferably Original Louisiana Hot Sauce

⅛ teaspoon kosher salt

Pinch of freshly ground black pepper

The dip to eat with boiled shrimp, crawfish, and crab is a simple combination of mayonnaise, ketchup, and seasonings. It seems like many different cuisines have a Thousand Island dressing–like combination such as this.

Mix all the ingredients in a bowl until well combined. This dip will keep in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to 3 months.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.