The Boy Who Got Stuck In A Tree: Part Ii

(Part I of this story can be found here. Go read it! Hurry!)

God sent me a sign.

Specifically, a sound.

It started as a faraway whisper, the crash of a distant wave, then grew to a lurid swish, perhaps something in the leaves, some lumberjack kicking his way through a pile. And it was getting closer. So close now that I was pretty sure it was a herd of deer being run by a mute hound, or a bear, or two bears, hungry bears, or a moonshiner dragging the corpse of his adversary, possibly being chased by the two hungry bears. Louder. So loud it was upsetting. Why could I not zero in on this sound? My chest was a tom-tom, my gun bounced in my hands. There’s just something about hiding three stories up in a tree with enough ammunition to murder a large nuclear family that heightens the senses.

The animal must be quite large.

It was right upon me.

Underneath my stand.

And then I saw: an armadillo.

The escape of butterflies into the bloodstream was at once electrifying and sickening. How had the armadillo gotten so close? I wanted to shoot it just for scaring me. If this was a sign from God, the sign said, “You suck at this.”

But wait. Another sound, more sinister, a sound that wanted to be heard, a stamping on the ground. Thunk. Bucks will do this during the rut, and it was the rut.

Thunk.

Behind me.

I turned off the safety, put finger to trigger, pivoted, and saw it.

A bird.

Not just any bird, but my brother: Bird. He was very close, twenty feet away, and not even wearing his orange. This was his way of showing me he was some sort of a Hunting Ninja. It was also his way of potentially becoming a Dead Hunting Ninja.

“I could’ve been a deer,” he said.

“I could’ve shot you,” I said.

“I’m sure you’d miss.”

He was always doing this, sneaking up on me, then insulting me. It was his primary way of communicating with those he loved. What I didn’t know was that Bird’s sudden appearance set in motion events that would change my life forever, and also change the life of at least one deer forever, a deer I would soon be shooting, which has a way of changing almost anything’s life.

He indicated that I should get down and follow him.

“Why?” I said.

“It’s something wrong,” he said.

I did what my brother said and got down, because while he may have lacked the ability to conjugate verbs, he would’ve known how to kill those verbs if they had been running through the forest. He was sixteen now, and quite the hunter. He’d already killed his first, and his second, and third. Actually, there was no telling how many he’d killed. He obeyed so few hunting laws, largely as a result of his believing that he had Native American blood, which he believed absolved him from all state and federal hunting and drug laws.

“Cherokee didn’t need no fucking hunting license,” he’d say.

What was the Trail of Tears like, I wanted to ask. Had that been hard, watching all his people die of smallpox? But also, I wanted to believe.

It was a lie our grandmother had told us about being descended from a Cherokee chieftan, a version of the same fairytale told to most poor whites and blacks across the South, a way of making us feel better about genocide and gambling. I’d heard such blood could earn me a college scholarship, which I believed was my passage out of this alien land, while Bird used this blood to explain his preternatural desire to learn things about animals by smelling their feces.

“What are you doing?” he said, while I was still in the tree.

“Unloading my gun,” I said. One did not merely shimmy down from three stories up with a loaded gun on his back. One took precautions.

We’d both attended a hunter’s safety course that summer, mandated by law. Pop and Bird were nonplussed. What could some game warden with a B.S. in wildlife management teach us about the sporting life? It was an insult. Not to me. I was curious as to what other men might teach me, particularly men who may have written books on such matters, or at least men who had read those books, or perhaps any book.

I learned much.

For example, I learned that it was preferable to shoot a deer in the heart, and not from a moving vehicle, or the window of one’s home. I also learned first-aid, in case the massive deer we’d just shot was actually a family member, and that it was best not to strap a dead deer to the hood of one’s truck, a common sight at our club, as the heat of the engine had been known to cook the deer, which would bloat the carcass, which would prevent the hunter from actually seeing the road in front of him, which might result in the additional slaughter of animals and people one had perchance not intended to slaughter. I also learned about the horrors of hypothermia and how one might grow disoriented and fall into a river and never be heard from again, and how to build a fire so as not to die from exposure, and how, in order not to fall out of a tree, one might tie oneself to said tree with a rope or harness, as though one were about to be launched into space.

Pop nodded in general approval of these lessons, even though tying oneself to trees seemed a bit excessive and womanish.

I took notes, while Bird took naps. Nobody was going to tell him, the Last Cherokee Huntsman, and also the First Blonde One, how to load his gun, or where to shoot from. He would shoot from wherever the hell he wanted to. Maybe a rooftop if he felt like it, or from a jet ski.

“Let’s go,” he said. “There’s hunting left to do.”

I wanted to take all eight shells out of my gun, but to oblige Bird, I only took the one out of the barrel. I put it in my mouth and descended the ladder.

“So, where are we going?” I said.

He turned and stared into the trees, as though he had heard something I didn’t, perhaps deer, or distant gunfire, or merely the ancient spirits in his head.

He walked. I followed.

In whispers, he explained what had happened: his three-wheeler had fallen in a hole. I was not to ask questions. We were still in the woods, still hunting. He crept forward noiselessly on the roadbed, gun drawn, while I trailed behind. This is what he called “stalking.”

Pop did not approve of stalking, but Bird didn’t care.

Stalking deer is not unlike stalking a human, in that both involve mobility, concealment, and a mild psychosis brought on by the inability to experience human love. Or so I believed. I wasn’t very good at it, and kept accidentally snapping twigs, making Bird turn and scowl.

“Watch where you step.”

“Sorry.”

It was hard to explain that my excess of garments prevented me from actually controlling the movements of my legs. Whenever I went to step somewhere, they jutted out aggressively as if they had agendas of their own, mostly concerning the destruction of small trees and shrubs. But I did attempt to place my feet more noiselessly, which meant I did not always watch ahead of me, which meant I often ran into my brother, who could not stop kneeling and smelling things.

“Don't be such an idiot,” he said.

“Yes, okay, sorry.”

I hung back. I let him do his thing. It was just too hard. We were just too different.

He was fearless. He would just hit people. He would laugh big bellowing laughs that frightened small animals. He would blow a snot-rocket right there in the middle of a baseball field, a jet of mucus erupting from a single nostril with enough force to clear his sinuses and disorient the batter. He was a badass. He had balls. Literally. He had shown them to me. They were enormous. Would mine ever be that big, I wondered? What did it feel like to be a man?

He looked so good in his hunting outfit. Jeans. Field jacket. Tall. Thin. Like a J.Crew model, if they wore Bowie knives. How could he get away with wearing so few clothes? Was he simply unafraid of the cold? Or did he lack the necessary nerve endings? And why did he insist on smelling everything? And where were we going? Didn’t Pop become very upset when we left our stands? What had compelled me to do this?

Bird was led by native spirits, but what led me?

Suddenly, he pulled up his gun and shot into the woods. But I had seen nothing.

“It was a deer,” he said.

It may have also been a hallucination. He wanted deer that badly. You had the feeling he would just punch a deer in the face if he got the chance.

That’s when we saw it.

Actually, all we could see were its handlebars.

His three-wheeler had fallen in a deep mud hole cut by a pulpwood truck and was now mostly underwater. Bird’s plan was for me to get in and push, since I had fat rubber boots, while he would help from dry ground, where it would be easier to laugh.

“It’s too cold,” I said.

I was thinking of the hypothermia lesson. The man in the video they showed us, he died.

“Just stand in the shallow part,” he said.

Something inside me changed. All my thoughts about the cold and the water and the idiocy of getting wet just vanished, perhaps because it was time to grow up, or because I had grown weary of being the family baby, or just that the air temperature had briefly frozen my brain. Whatever it was, I did it. I stepped in.

There was no shallow part.

What happened next would likely be described by medical professionals as “drowning.” The water was five feet deep where I’d gone in, and I went into immediate shock. I sort of bobbed and floundered there for a second, like a buoy, owing to the many layers of clothing, which proved astonishingly impermeable to water, and flailed, and splashed, not quite standing, not quite falling.

It all happened in a heartbeat, and then I managed to scramble and hurl myself onto the edge of the pool, that carpet of pine needles that served as my own private Normandy. When the mud drained from my ears, I could hear Bird laughing the loudest laugh that had ever been laughed outside of a mental hospital, so loud that any nearby deer would not have run, having mistaken it for a distant car accident involving cattle.

And I knew: I was going to get hypothermia and die.

“You got a little wet,” Bird said.

I wanted to ask him: What does it feel like not to have a human heart? Was it fun?

My gun lay against a tree several yards away. I briefly considered the moral implications of fratricide. Nobody would know. Hunting accidents happen all the time. A gun can slip, fall, accidentally discharge six or seven times in one’s brother’s face.

I started to shake. Bird attempted to reach his handlebars from dry ground, while I lied there and tried to remember the various stages of hypothermia, which started at anxiety and ended in what the narrator explained were “feelings of unreality” and “death.”

“You look a little pale,” Bird said.

“What color are my lips?”

“Green,” he said.

“I’m going to die.”

Thankfully, I was wearing cotton, which was very good at holding water next to the skin, speeding up the dying process. I began to disrobe, first my boots, then my coveralls, then various inner garments. That’s when my book fell out.

I had forgotten about my book.

I’d gotten the idea a few days before, as a way to cure the endless boredom. The idea had come to me in a vision, and I had been careful not to say anything. My father would be upset. I’d already gotten in trouble for reading at church, and this would be much worse. They would all know why I hadn’t killed anything. They would blame literacy.

“What the crap is that?” Bird said, looking down at the wet paperback.

“A book,” I said, teeth chattering. “It’s got all these words in it. You should get one.”

It was Watership Down, a book about Communist rabbits who worship the sun. I was glad he didn’t ask.

“Shit, man,” said Bird. He was shocked. He might as well have discovered me carrying tampons or a gymnastics brochure.

“Don’t tell Pop,” I said.

Most of my clothes were now in a pile, and my exposed skin burned. All I wore were boots, pants, a sweatshirt, all sodden and slowly hardening. The man in the video said you could die in just an hour or two.

I needed to go. Where to, I didn't know.

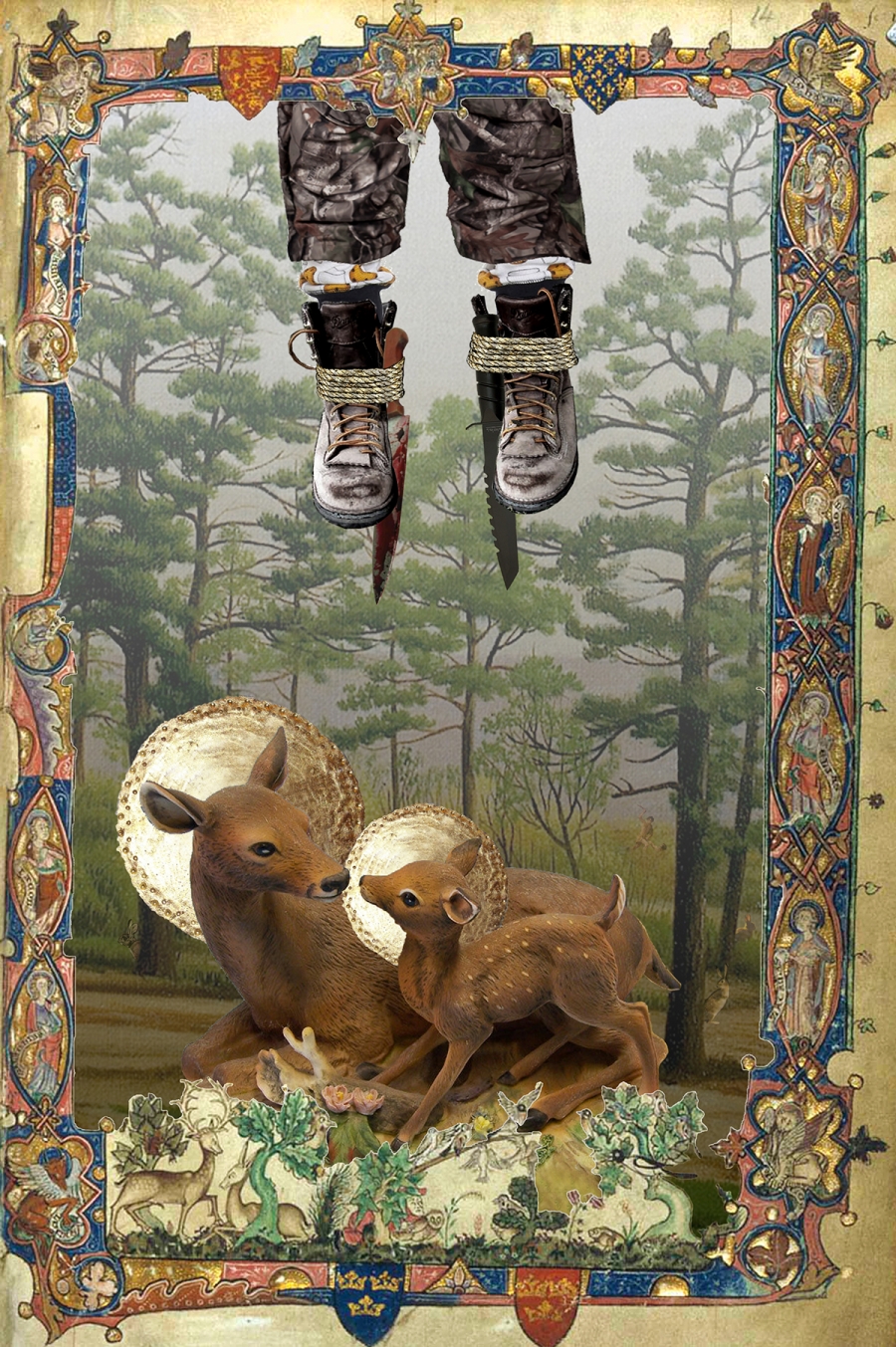

"The Boy Who Was Stuck in a Tree," 11" x 16.5", digital collage, 2013, Dayton Castleman

The best thing about dying from exposure is that it gives you time to reflect. I walked deeper into the woods and thought a lot about my situation and my family and my brother and father and this ridiculous childhood. Why couldn’t I have been born to a man who loved libraries, or circuses, or museums? My mother’s father loved movies. He’d run a film projector at The Joy, a theater in Rolling Fork, Mississippi. Every Saturday, he took Mom. She stayed there all day, watching Westerns and monster movies and Gone With the Wind about a hundred thousand times, which I guess is a kind of torture, but it sounded dreamy, sitting alone in the balcony while one's father sat a few feet away threading reels and smoking cigarettes and reading the funny papers.

Right about then, my book was beginning to chafe.

The feelings of unreality came quickly.

Trails crossed, forked, changed. What I thought was, I should get back to my stand and just wait like nothing had happened and maybe Pop wouldn’t notice that I’d lost all my clothes. Around bends, I saw visions of darting brown things. I found myself stopping for no reason, turning to look into the woods. Had I seen something move?

What in the hell was I doing?

What I was doing, I guess, was hunting.

I looked for the sun, but the sun had wrapped itself in a warm envelopment of clouds. My face felt like the surface of a refrigerated ham.

How could I warm up? I could always start a fire, which the video explained was a way to save my life and also burn down the forest. Since then, I’d taken to carrying matches, which I transported in a small black watertight film canister.

I found a small clearing by the trail and gathered twigs and leaves. I crouched, lit the pile. The fire caught and spread; it was a successful fire. So successful that it wanted to become a bigger fire, and I wondered: When does a fire in the forest become a forest fire? It was an interesting question. Another good question was, if forest fires are wrong, why does this one feel so right?

Is this what they meant by feelings of unreality?

He did what, they would say.

Started a fire, they would say. Because he thought he was going to die.

And they would laugh and laugh.

I put the fire out and kept moving.

I knew what I had to do.

I had to find my father.

I came to a fork, and went toward where I thought he might be.

I put a round in the chamber. Yes. I was hunting now.

Pop had said he was going to the Cutover, a desolation in the very center of these woods—a clearing approximately the size of Central Park and created, not by thoughtful urban designers, but by paper companies who took all the trees and left a bare gray landscape that looked like somewhere you’d find a mass grave, or an art project about mass graves. Deer loved the Cutover, because they could hide there, which is why Pop loved it, and now I scanned its gnarly expanse for him. He would be in a tree, of course, and there weren’t many.

I walked along the edge for a hundred yards or so, and I saw him in a tree. And despite that I had lost my hunter’s orange vest somewhere up the trail, he saw me. He waved. I waved back. But no, he wasn’t waving. He was gesturing. Pointing at something out in the Cutover, something he wanted me to see.

I saw it. A deer. No. Two.

About 200 yards away, grazing, heads down. Big one, small one. No antlers.

Seeing anything in the wild got the heart pounding. Spit fills the mouth. Blood heats. Butterflies tumble. A large doe was valued largely as an indicator that something with antlers might be nearby, but the Cutover was empty. Pop and I, communicating in slow gestures, had scanned the hills and seen no buck. These two deer were it.

There was no question of my not shooting.

It would be an easy shot, as they were not moving.

So, my first deer would be a woman. Somehow, this seemed fitting.

My father must have been proud, as from his vantage he saw me raise the gun to my shoulder and prepare to shoot my first deer. This is what he wanted. I put the bead of my iron sights where the heart was.

Bang.

I pulled up and looked with both eyes. The deer had not moved.

200 yards was far.

Bang.

More nothing.

Bang.

Additional nothing. Three murderous shots and they hadn’t moved. It was like they hadn’t even heard the gun. Were they deaf? Was I shooting a family of disabled animals? Was that even legal? I looked at Pop, who gave me a thumbs up. I guess he was saying, Okay, great, you’re doing great, which I wasn’t.

I put the gun to my shoulder again. Did I really want to do this? Why couldn’t the deer run after the first shot, like they’d always done, so I wouldn’t have to ruin their day and mine? I was fine with missing, really. They were so far away. Pop would understand.

But no. They just stood there. Daring me to do the thing that everybody said would make me a man. But I didn’t want to be a man. I could settle for being a child forever, or maybe a woman, or a librarian, or anything that didn’t have to kill things.

Five rounds left, one bullet for each stage of grief.

Bang. Denial. My gun was broken.

Bang. Anger. I hate my family, and I hate these deer, even if they are deaf.

Bang. Bargaining. Okay, Jesus. Remember how I said I would become a preacher if you let me kill a deer today? I’ll do you one better. Not only will I stop touching my penis, except to wash it and dry it, which I think you are probably okay with, but I will become a missionary to some dangerous place, like Nigeria or Atlanta. Yes. I will serve you. Just please let me explode this deer’s head off its body. Also, I will be nicer to old people. Amen.

The deer had moved a little, but continued to graze, unperturbed. Two shots left.

Bang, another miss. Depression. I am a terrible human being. I can do nothing right. I should do us all a favor and turn this gun on myself, although I would probably miss then, too.

One shot left. What would this come to? Would I have to charge at them with a stick? Would Pop come down and hand me his gun? In that moment, if I thought it’d have made him proud, I would have thrown a grenade at a whole damned family of deer.

Now Bird had found us. He had heard the shooting. He watched. He judged.

One more. Make it count.

A short, naked tree stood nearby. It looked dead. I walked to it, and placed my rifle in the crook of its lowest branch. I aimed. Help me, Jesus.

Bang. Acceptance.

I was no longer a child.

I stood ten yards away from the larger deer. It was still breathing. I’d hit her in the gut, but she was not dead. Bird and Pop stood behind me, watching. This was my kill. Becoming a man was complicated, filled with decisions. Such as: Do I just stand here and let it suffer?

“Shoot it,” Bird said.

Pop said nothing. His expression was neither one of satisfaction nor its opposite. He was merely surveying the fact of what was happening.

But I couldn’t do it. How close to do you stand to it? Do you put the barrel against its head? I had to work up the courage. This was supposed to be the easy part. It was lying right there. I usually kept one or two rounds in a pocket, just in case. I found one. It was wet. Could I use it? Should I? Would it misfire? Explode? Blind me?

While I was vocalizing some of these questions, my brother shot the deer in the head.

And that’s when we saw the other deer, the baby one.

A yearling. The saddest part is how it just stood there, watching, almost leaning into the clearing where we all stood, as though it wanted to run to its mother, but didn’t know if it had permission.

For some reason that I’m not sure I know even now, this only embarrassed me further. I had killed this animal’s mother. It was the most heartbreaking thing I had, or have, ever seen with my own eyeballs. I tried to tell myself that the fawn was not thinking about its dead mother, that when it went to bed that night, deep down in some secret thicket, it would not feel alone for the first time in its life. And that is what made me sad.

I tried to shoo it away, but it did not move. I waved my gun at it, and it turned its head, and that’s when I saw that the right side of its face was mostly gone. Its muzzle was split in two, bleeding, its teeth and jawbone exposed, the flesh of its jaw a haze of gore. I had done this. But how? Was this the ghoulish result of the final bullet, ricocheting off some dead tree? It would take a long time for this animal to die. It would starve. Get an infection. Die of shock. Never grow up.

It turned and walked away, slowly, into the Cutover, and was gone.

That was the last time I went hunting, or rather, the last time I tried to shoot anything. For five more years, I would get up on so many mornings in November and December and January at 4:00 A.M., only this time I made sure to bring books.

I slipped them into my trousers every morning, and nobody said a thing. I read without ceasing, Tolkien and Verne and Dickens and Twain and Poe and Hemingway and Steinbeck, and then moved on to the weird stuff, the Asimov and Heinlein and Koontz. These were hearty distractions from the tedium and the horror.

I think Pop knew. It was our agreement. I would not resist the hunting, and he would not resist the reading, and every deer season, as if by miracle, my standardized test scores would improve.

Besides, I'd killed a deer. I'd done my part. Really, I'd killed two. There had been no fanfare. Pop had taken no pictures, sent them to no magazines, put them up on no general store walls. They didn't even make me drink the blood. I hardly remember the gutting.

I just kept reading and didn't think about it.

When I went to college, Pop kept asking me to come home and hunt, and I had all sorts of new excuses: that I needed to study, or work, or wasplanning to have my larynx removed, or maybe I was planning to have blood in my stool this weekend and couldn’t make it. Eventually, he stopped asking.

Hunting was good for me. I am grateful for the obvious lessons, of patience, and quietude, and reverence for a wild and unruly creation, and how to locate genitalia whenever they are hiding under thirty layers of flannel, and how to be a writer, which also involves getting up very early, and sitting, and staring, and going slowly insane.

And I wonder: Will I be able to give my children adventures like these? On Saturday mornings these days, the darkest and scariest place we go is the public library, which, if you’ve been to some of the public libraries in my town, is a lot less safe than it sounds. Perhaps my children will one day write a memoir about how terrible it was to go to libraries and bookstores with their father every weekend, and how much they hated it.

“At least I didn’t make you cut out deer anuses,” I will say.

Occasionally, the old urge rises within. I will step outside on a gloriously cold morning before sunrise, briefcase and book in hand, the stars laughably bright, Orion standing at the ready, a song in my blood. Today the deer will be moving, I think to myself, and wonder if those two wonderful men are somewhere in the woods—Bird chewing peyote buttons and taking deer scalps, Pop sitting and staring out into the Cutover. I almost wish I was there with them. But these stories aren’t going to write themselves.

On our way home from Mississippi during our last visit, we were speeding along the highway, green and brown falling away on both sides, and I found myself scanning the fields for ghosts. And I saw them.

“Deer!” I said, pointing.

“Deers!” my children said.

“Where?” said my wife.

But it was too late: we had passed them. My wife and children are too slow. They don’t understand. You must look quickly, or they are gone.