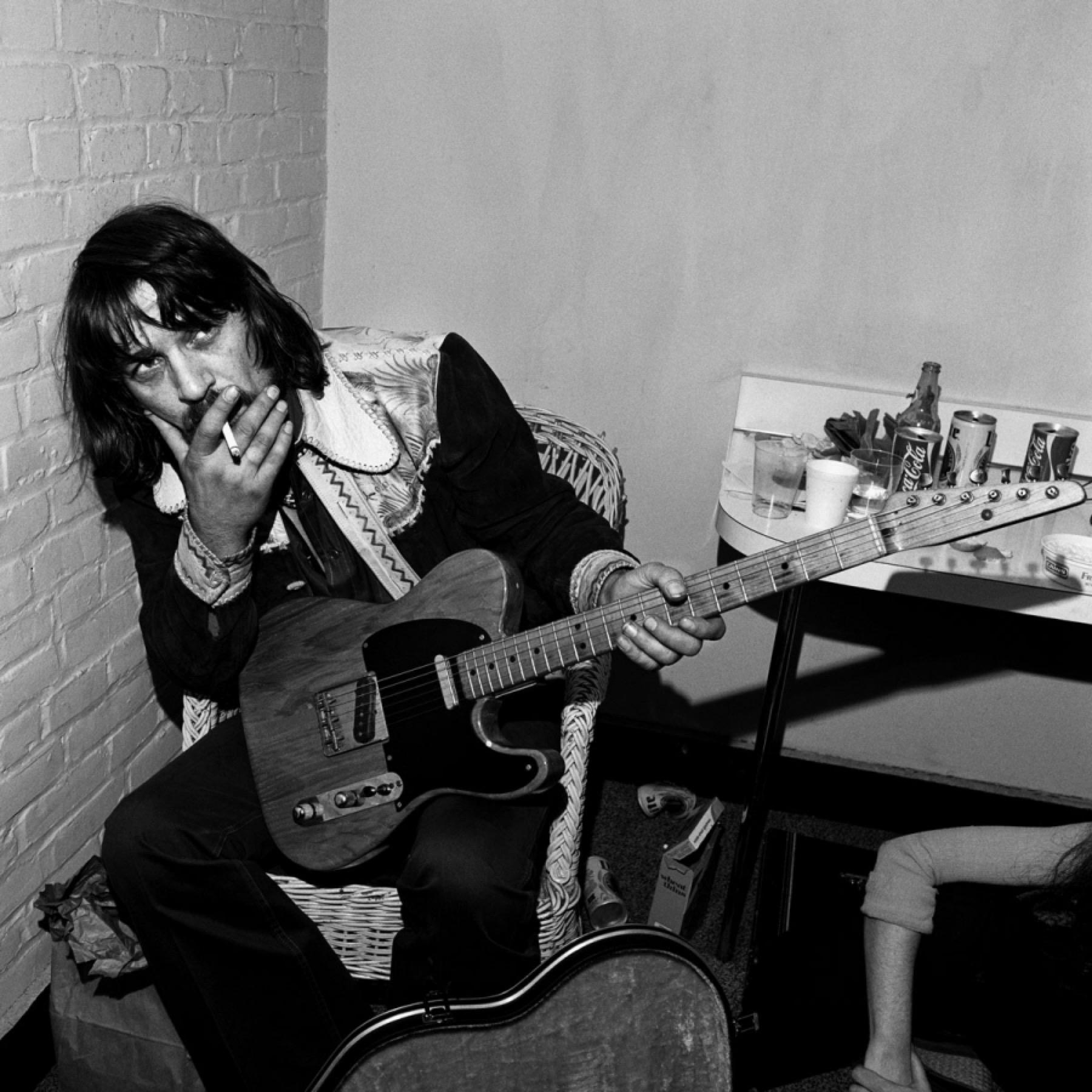

“Waylon Jennings, Cambridge, MA, 1976” by Henry Horenstein, horenstein.com

CRAZY TO LOOK IN THE EYE

By Will Stephenson

Michael Streissguth’s Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville

Several years ago, outside of a dive bar in Lorena, Texas, called Papa Joe’s, the country singer Billy Joe Shaver shot a man in the jaw for telling him to shut up. It’s old news now, something he jokes about in concerts. He even wrote a song about it, “Wacko from Waco.” Still, I went to see Shaver in October, when he came through Little Rock, and as he stepped onstage the shooting made an immediate sort of sense. Of course he did: it’s exactly the kind of incident it would’ve been necessary to invent, if it hadn’t actually happened, in order to accurately describe him and the effect he has on an audience. There is even now, at 74, something grizzled and reckless and slightly fear-inspiring about his presence.

Onstage he wore a black necklace with a large reptilian tooth or claw hanging from the end. He spoke in mumbled asides and koan-like non sequiturs: “This is the worst song I ever did,” he’d say, or “Ask Evander Holyfield, he’ll tell you.” Introducing a ballad, he told an eight-minute story about his divorce, his favorite truck, and the first time he dropped acid. By the show’s halfway point, he’d already made at least one elderly man in a leather vest and ponytail start to cry and leave to collect himself outside. That was during a song called “Live Forever,” and we all understood.

As the night wore on, he inevitably brought up the shooting in Lorena as well, which he called “that bit of business down in Texas.” He wanted to insist that one detail had gone misunderstood in the public record, that he didn’t actually say something he is supposed to have said. As he quoted the line, though, he laughed a little suspiciously with what looked like uneasy pride. And anyway it’s there in the affidavit, which you can find online: before the shot was fired, according to the document, Shaver was heard by witnesses to ask his offender, “Where do you want it?”

Shaver’s big break came in 1972, at a music festival in Austin called the Dripping Springs Reunion, when Waylon Jennings stumbled drunk out of a trailer, heard Shaver playing one of his songs, and promised to record a whole set of them (a promise that would produce the album Honky Tonk Heroes). The festival was organized by Willie Nelson, already a kind of saintly stoner guru figure, and it occupies a central place in the new book Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, by the country music historian Michael Streissguth. According to Streissguth, Dripping Springs “announced the old guard’s step to the side for youth culture,” as the lineup itself marked an important moment of intersection between country music’s elder statesmen, clean-cut stalwarts of the Nashville Sound like Hank Snow and Roy Acuff, and its up-and-coming new school, exemplified by figures like Shaver and Jennings.

This tension, and the new sounds that resulted from it, are the subjects of Streissguth’s book, which pairs an absorbing portrait of the Outlaw Country movement with a slightly less convincing argument about its cultural significance. Its heroes are Jennings, Nelson, and Kris Kristofferson, along with the likeminded songwriters, like Billy Joe Shaver, who emerged in their wake, a generation Streissguth grandly credits with unseating the Nashville-based country music establishment and radically impacting the genre in the process.

Outlaw opens on a classic note of anti-Southern condescension from the 1960s. “Nashville,” writes a New York jazz critic in town on assignment, “is a pallid, tasteless town.” The critic, Streissguth writes, went on to attack “the quality of Nashville’s food, urging visiting New Yorkers to bring their own canned goods because the city’s restaurant fare soured the stomach.” With a few notable exceptions, country music culture has been provoking these sorts of patronizing, casually repulsed responses from the start, or at least since 1926, when Variety ran a column dismissing the burgeoning “Hill-Billy Music” scene as “poor white trash”: “The great majority, probably 95 percent, can neither read nor write English. Theirs is a community all to themselves. [They are] illiterate and ignorant, with the intelligence of morons.”

The Outlaws were among the exceptions. They may have been white trash, but they weren’t illiterate or ignorant. Albums like Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger (1975), Jenning’s Dreaming My Dreams (1976), and the compilation Wanted! The Outlaws (1976) were critical favorites and full-tilt, chart-topping cultural events—mellow, backwoods dispatches that nevertheless sounded progressive, even anti-establishment, and managed to captivate the general record-buying public in a way that few country acts ever had. They were evidence that the counterculture had finally breached the South and had begun influencing even its most native forms, a rare period of overlap, it seemed, between popular and redneck tastes (between the rest of the country and “country”).

It’s a story that’s been told before in detail—in biographies, memoirs, and cultural histories like Jan Reid’s Austin-centric The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. Streissguth’s approach, in keeping with his previous books on country icons like Jim Reeves, Eddy Arnold, and Johnny Cash, is to focus on Nashville itself, to track the era by the observable progress of the industry’s center of gravity. We watch as the city undergoes a transformation from the ostensibly “pallid, tasteless town” on page one to a vibrant if short-lived bohemia, a unique cultural stage with a cosmic cowboy dress code and drum circles featuring Shel Silverstein and Allen Ginsberg.

Outlaw provides rough sketches of the scene’s three prime movers and their respective backgrounds—all born in Texas, all initially overlooked by the monolithic Nashville fiefdom—before tracing their careers over the course of the 1970s in sections that alternate and overlap. Streissguth seems especially fond of Kristofferson, whom he portrays as having cleared the way for the others with his singular blend of Oxford intellect and rough-hewn naturalism. Certainly he wrote great, groundbreaking songs, but Streissguth’s claims for his significance can get out of hand—that he “owed more to the English poet William Blake . . . than to the honky-tonk king Hank Williams,” for instance, or that he alone can be thanked for “introducing mature themes to country music.” Surely that would be news to Hank Williams.

Waylon Jennings, meanwhile, appears as a kind of miraculous character, ravaged and nervy from speed, and narrowly dodging death and ruin at every turn. Whether giving up his seat at the last minute on the flight that killed Buddy Holly, contracting hepatitis at an Indian reservation, or hiding out on his tour bus from the Hells Angels, Jennings is a person for whom survival itself, to say nothing of his music, was touch and go. Willie Nelson, on the other hand, congenially and resourcefully navigates a career that only seems to improve, and that none of the others would begrudge him—he’s just generally agreeable. One of the highlights of the book comes from the guitarist Billy Ray Reynolds, who remembers getting stoned once out in the wilderness of Nelson’s farm in Ridgetop, Tennessee. “There were thousands of frogs, and we were sitting there on the dirt listening to them,” he says. “There were just unbelievable sounds.” Nelson began pointing out the different registers: altos, sopranos, and basses. “It was kind of strange,” Reynolds says, “having somebody like Willie Nelson talking about the orchestrations of a frog pond.”

The critic Hugh Kenner once dismissed a biography of Samuel Beckett, whom he had known personally, by claiming he’d stake one evening “watching Sam Beckett play billiards” against the entire book. There are moments, reading Outlaw, when you begin to see what he means. The book’s massive cast of Deep South freaks and reprobates are readymade for nonfiction, all of them self-invented and self-aggrandizing, and the anecdotes and profiles here are appropriately gripping. Often less impressive, though, is the connective tissue, the narrativizing and sweeping generational diagnoses that can seem at best self-apparent and at worst baffling. The image of Johnny Cash prying open Waylon’s dashboard with a crowbar looking for drugs is haunting and illuminating; I’m not so sure about some of Streissguth’s more far-reaching insights, such as that country music’s newfound openness to rock influences “recalled Lyndon B. Johnson’s pragmatic negotiations with black America’s inevitable push for civil rights.”

This is at least partly an issue of genre, in this case the underdog group-biography in the tradition of Peter Biskind’s New Hollywood chronicle Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (the influence might be direct: Streissguth more than once compares Nashville’s network of interrelated labels and publishing houses to “a Hollywood movie studio”). These books center on a dull and conservative institutional status quo that’s shaken up by a sprightly avant-garde. In Nashville’s case, though, the formula doesn’t quite ring true. This is the genre, after all, of George Jones and Charlie Rich, of the Louvin Brothers’ “Satan Is Real” and Eddy Noack’s “Psycho.” Kristofferson and company may have sold a lot of records, but is “renegades” really accurate? In fact, Streissguth’s own previous books could serve as correctives to this one’s depiction of the earlier generations as staid and outmoded.

To make his point, Streissguth continually refers to a “wall between establishment Nashville and the emerging youth movement in country music,” but what he actually portrays is a far more nuanced and interesting scenario—from the multigenerational Dripping Springs Reunion lineup to Johnny Cash recording Kristofferson songs and regularly hosting the younger artists on his TV show. We learn that even the idea for Wanted! The Outlaws, the first platinum-selling country album and a cornerstone for the Outlaw mythos, came from Jerry Bradley, the head of RCA Nashville (about as “establishment” as you can get). One of the strange things about reading this book is that you become increasingly both enamored with the cultural moment and confused as to what it meant. It was a raucous lapse in traditional Southern conservatism, but also largely a branding strategy; radical and new, but also just another rotation in an ongoing cycling through the genre’s familiar, almost rigidly conventional set of personas. This is partly why “progressive country” always sounded like an oxymoron, but then, if anything, the paradox is what gave it its power.

There was at least one other outlaw in attendance at the Dripping Springs Reunion who isn’t present in the book: Larry L. King, the writer and member of what Steven L. Davis has termed the “Texas Literary Outlaws,” a kind of Southern outpost of the New Journalism. King covered the festival for Playboy and saw it all in starkly different terms than Streissguth’s radical-utopian account. He meets one of the promoters, who paints Willie Nelson as a “goodhearted raggedy-ass who might have to sell his horses or find his wife a part-time job” for all the money he’ll be losing on the event. Then two employees walk in carrying sacks of cash—$40,000 from “advance ticket sales in San Antonio” alone. Later he finds himself reflecting grimly on Nelson’s working-class tales of “how cold it is sleeping on the ground, of life’s rough and rocky traveling.” The contrast is too much for him. “I’d been a Willie Nelson fan for years,” he writes, “his mournful, melancholy music never had failed to reach me. But now all I could think of was Willie picking up the phone in the Waikiki Hilton to call room service, he and God grinning together at the irony of his poor-boy songs.”

Which is closer to the truth: the cynical opportunist or the humble farmer blissing out to the orchestrations of a frog pond? There’s probably some essential truth about country music and its icons to be found in the contradiction itself, but then they’re both just ideas.

Ideally, like Kenner, I’d recommend seeing them in person before you make up your mind. Most of the Outlaws have settled down, died, or, in Willie Nelson’s case, priced themselves out of accessibility, but there are still those, like Shaver, who’ve kept it going—touring dives, telling stories, shooting the occasional person in the jaw. After the Shaver concert in Little Rock, I remembered an oddly self-reflexive Kris Kristofferson song called “The Fighter” quoted in Outlaw. “There wasn’t nothin’ like Billy Joe Shaver,” he sings, calling him “crazy to look in the eye.” “He put on a show that was sad as it should have been, and nobody even knew why.”