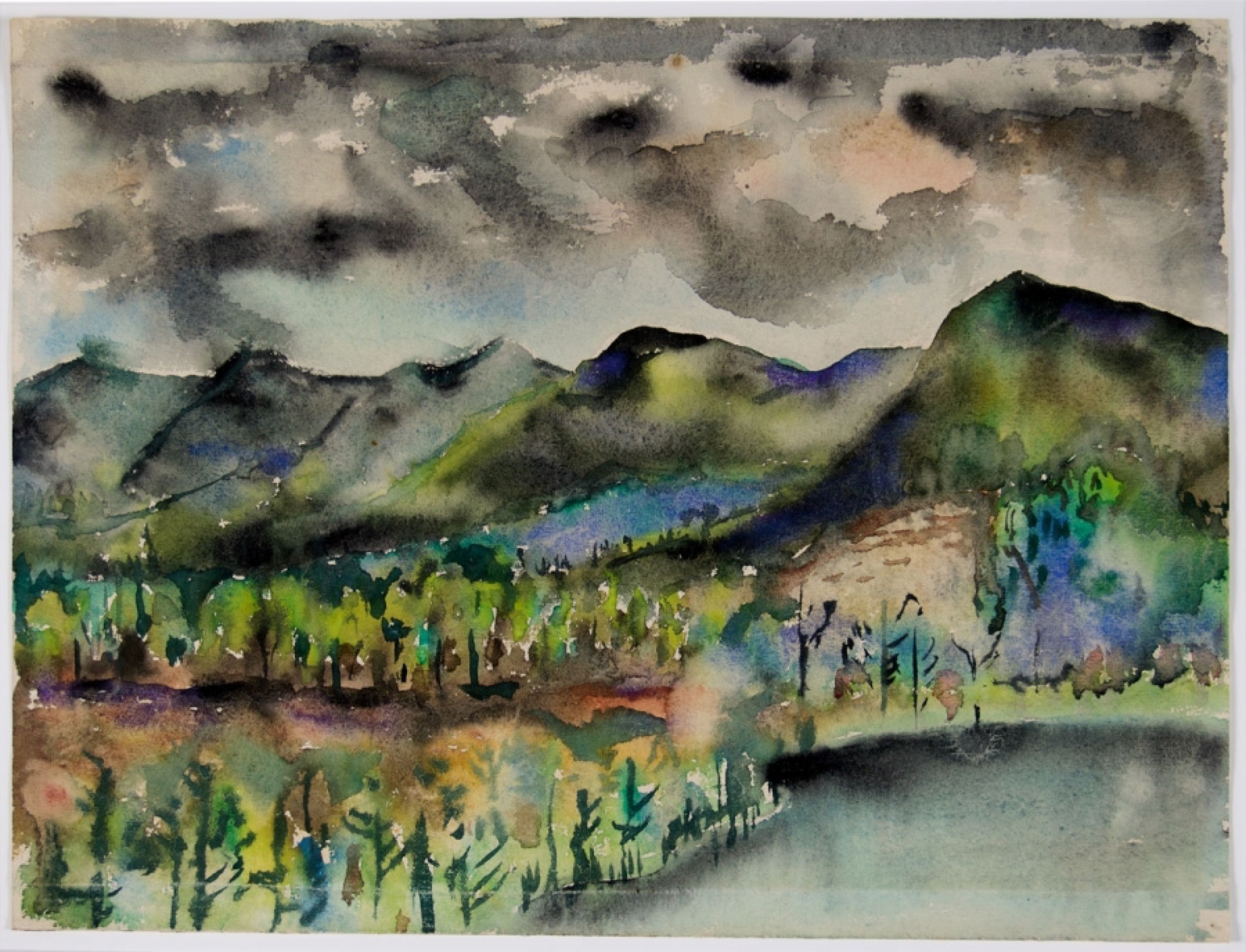

“Black Mountain, Lake Eden” (1954), by Joseph Fiore. © Estate of Joseph Fiore. Courtesy the Asheville Art Museum

Black Mountain Music

By John Thomason

G

ERMANS TO TEACH ART NEAR HERE, read the banner headline in the Asheville Citizen on December 5, 1933. In the accompanying photograph, the two émigrés in question look formal and tentative, their hands crossed at their waists, their bodies not quite willing to turn completely away from each other and toward the camera.Anni and Josef Albers could be forgiven for their apparent reticence. Their departure from Germany was sudden, due largely to what the Citizen obliquely described as “the national educational policies of the new Hitler government.” The faculty at the Bauhaus, where Josef had taught a renowned design course for the past decade, elected to close the school rather than accept the Nazis’ demand to bring Party members on staff. Knowing they could not comply with censorship and might be targeted even if they did, the Alberses quickly decided to flee to the United States. Luckily, Anni and Josef were invited to become faculty members at a new school in Black Mountain, North Carolina. They knew neither what nor where North Carolina was, but an American student of theirs had assured them it was “beautiful country, very southern and very mountainous.” Josef wrote back with interest but confessed he could not speak English. (“All I knew was Buster Keaton and Henry Ford,” Josef later remembered.) “Come anyway,” the reply read, so they did.

What they found when they arrived at their new lodgings in Robert E. Lee Hall (the name predated the college) was true to their student’s description, though perhaps more rustic: Anni was shocked to discover a thumbtack on one of the hall’s stately Doric columns, not realizing it was made of wood. The campus sat snug in the foothills above the small town east of Asheville, and it had previously seen human activity only in summer, when the property’s owner, the Blue Ridge Assembly of the Protestant Church, held religious conferences. Shepherding Protestant conferees off the property in time for the fall semester was to prove a perennial challenge in the early years of Black Mountain College, but it was worth the discounted rent.

Such makeshift arrangements would characterize the college’s operations every year for the two decades it remained open. Black Mountain’s sluggish fundraising was no surprise given how radically it broke from the American educational tradition. The school’s charter stipulated that it would be wholly owned by its faculty and students—with no outside trustees—who were also required to perform manual labor to contribute to the maintenance and upkeep of the college. Chopping wood, harvesting crops, and occasionally putting out forest fires were as integral to campus life as reading Plato. Education was supposed to take place everywhere: in dorms, on hiking trails in the woods, or in the large dining hall where students and faculty ate side by side. (And ate well—that is, “if you like the kind of Southern cooking which cooks vegetables in grease,” according to one alum.) The virtues for which the school would become famous are now standards in the PR literature of American colleges: close interactions between faculty and the small student body, hands-on interdisciplinary collaboration, and casual encounters of creative and intellectual epiphany.

Fine arts were considered the center of Black Mountain’s curriculum. College founder John Andrew Rice believed art-making forced students to make and justify choices, instilling a more responsible form of knowledge than mere memorization or recitation. Rice had agonized over the choice of appointing someone to head the art department, but when he explained his philosophy to Philip Johnson, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Johnson recommended Josef Albers. At the Bauhaus, Albers had eschewed traditionalist art education, which focused on the repetition of established techniques and the duplication of classical works. Instead, his teaching reduced visual art to its most basic constitutive elements—lines, color, material—and considered them in simple isolation. This way, lazy and received habits of seeing could be broken and developed anew.

This emphasis on experimentation, the independent testing of received wisdom, was what set Black Mountain apart from the more permissive, reflexively affirming progressive schools in the United States. Rice felt that Albers embodied a rigor that could truly realize John Dewey’s original vision “to educate a student as a person and as a citizen.” By learning to make informed, responsible choices in art, students would learn also to do so in life. But first they needed to learn how to see what was right in front of them. So, despite his halting English, the day Josef Albers arrived at the college he declared his intentions succinctly: “I want to open eyes.”

One April afternoon many years later, there was a slight commotion in the dining hall. Curious students and faculty stopped to watch a stranger tinkering under the lid of the college’s grand piano with the aid of a number of bolts, screws, and leather scraps. That evening they found that same man—who, with his pronounced crew cut and rather formal black-and-white attire, looked something like an undertaker—seated at the piano for a performance. When he hit the keys, it became clear from the percussive symphony that followed that he had fastened those bolts and screws between the piano’s strings. The audience, which included Josef Albers, was delighted. They were delighted, too, by the conversation held over coffee after the performance, during which the pianist explained that he hoped his composition could function as a model for the integration and improvement of natural human faculties—the building of a better society. It was a fitting paraphrase of Black Mountain’s mission.

In fact, John Cage’s performance was unplanned. It was 1948 and Cage was a broke but up-and-coming composer in New York. Earlier that month he had been invited to Los Angeles to perform his new piece, Sonatas and Interludes, but he had no way to get there. So Cage and his partner and collaborator, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, convinced a neighbor in their Lower East Side tenement building to loan them her jalopy. En route to California, the pair was invited to visit Black Mountain, which by then had relocated to property it purchased at nearby Lake Eden and “had a considerable reputation as a place where the welcome mat was out for innovators,” according to Martin Duberman, author of the most comprehensive history of the college. (Ever eager to be part of the artistic vanguard, Cage had been seeking an invitation to Black Mountain since shortly after its founding. In 1937, though in his mid-twenties and relatively new to music composition, he wrote asking for a teaching position; in 1942, he wrote again to propose the establishment of a Center for Experimental Music. Neither effort was successful.) Upon finally arriving on campus, Cage was so inspired that he decided to stage an early debut of the new piece, which would come to be considered the pinnacle of his work in the percussive “prepared piano” style.

Cage was quick to a broad, full-mouthed smile that belied his formal appearance, and he was as charming to the college community as he was charmed by it. His reception was encapsulated by the surprise he and Cunningham found when they returned to the jalopy after their five-day stay: “a large pile of presents that all the students and faculty had put under the car in lieu of any payment,” Cage remembered.

“At Black Mountain,” Cage wrote to Anni and Josef Albers as he continued west, “I see that people can work still together.” Josef in turn invited Cage and Cunningham back to be instructors for the upcoming summer session. Though the job came with little remuneration, it offered tremendous freedom: Instructors were told neither what to teach nor how to teach it.

The summer was every bit as rapturous as they had hoped. Cage and Cunningham were able to arrange for some of their friends to come teach as well, among them Willem and Elaine de Kooning and the sculptor Richard Lippold. Every morning Cage and Cunningham had breakfast under the campus’s lush canopy with the design autodidact Buckminster Fuller. The summer saw Fuller’s first attempt to raise one of his signature geodesic domes. He was unfazed when the structure collapsed under its own weight: “I only learn when I have failures,” Fuller said. Cage never forgot that response.

After twenty-four years of educational experimentation and financial struggle, Black Mountain College closed in 1956. Today it is remembered primarily for its tremendous impact on the visual arts. Among the famous painters to emerge from its tiny student body (yearly enrollment was consistently well below one hundred) were Robert Rauschenberg, Kenneth Noland, Susan Weil, Dorothea Rockburne, Ruth Asawa, and Cy Twombly. But it’s also fair to say that the most notorious experimental music composition of the twentieth century would likely never have been composed or performed if not for its cultivation there. John Cage’s two terms as a summer instructor, four years apart, bookended his larger transformation from a critically accepted, if minor, experimental musician to perhaps America’s most controversial living composer. It began with a food fight in Black Mountain’s dining hall.

For his first summer at the school, Cage devoted his performances solely to the music of Erik Satie, a then-obscure French composer who emphasized duration and rhythm as opposed to harmony. In one of his lectures, Cage favorably contrasted Satie with Beethoven, whose influence, Cage declared, “as extensive as it is lamentable, has been deadening to the art of music.” Cage knew he had uttered “heresy,” and many of Black Mountain’s German émigré faculty were furious. One day at lunch, rector of the college Bill Levi tapped his glass and somberly announced that the faculty had become so divided on the critical issue that they had to resort to an unprecedented measure to resolve it. He then decreed a duel in which the Beethoven partisans would wield Wiener schnitzel and the Satie sympathizers would lob flaming crêpes suzette. Conflicting accounts describe what ensued; according to one student, “some thirty people got themselves pretty messed up.”

The capstone of Cage’s summer-long celebration of Satie was a staging of the composer’s one and only play, The Ruse of Medusa, a proto-Dadaist farce whose unclear, ambiguous scoring portended the development of Cage’s own techniques. The erratic, hysterical performance epitomized the interdisciplinary, collaborative, and irreverent ethos of the college. The de Koonings designed and constructed the sets, Lippold contributed costuming, and resident playwright Arthur Penn directed; Fuller, Cunningham, and Elaine de Kooning starred. The joyous performance healed the wounds still festering after Cage’s anti-Beethoven broadsides, and it was widely considered the highlight of the term. “How can we thank you appropriately for all you did for us this summer?” Albers wrote to Cage.

By the time he arrived back at the college for another summer session in 1952, Cage had fully abandoned, as he later put it, “the traditional idea that [an artist] had to say something.” The Alberses were gone—Josef was now running the art department at Yale—and their departure epitomized the college’s drift away from its Bauhaus origins. Expressionists, personified by the new rector, the poet Charles Olson, had come to dominate Black Mountain’s new guard.

At this point Cage was interested neither in the controlled experimentation of Albers nor in the expressionism of Olson. Rather than promote the artist as a scientist or as an agent of unfettered personal expression, Cage instead wanted to eliminate the artist from art altogether. “The highest purpose is to have no purpose at all,” he later summarized. “This puts one in accord with nature in her manner of operation.” The art critic Calvin Tomkins noted that this viewpoint put Cage at odds with “the most basic assumptions of Western art since the Renaissance”—that art should disclose meaning, and that something interior to the artist could contain some transcendent truth worth expressing. For Cage, the only legitimate source of beauty and truth was instead the indeterminate and random workings of nature and the objective world. The pretensions of artists could only get in the way.

Cage’s culminating development of this ideal began, once again, in the dining hall of Black Mountain College. He insisted that the most important teaching at the college took place over lunch. Indeed, he later claimed to have conceived his Theater Piece No. 1 over a meal and staged it in the dining hall that same evening. As with many compositions from this period, Cage systematically randomized his process with the help of the I Ching: The results of a simple coin toss would lead him to a number in the book, which would determine the quantity and length of his score’s sections. With this piece, however, he relinquished even more control. He composed no musical notes to speak of, instead assigning his various performers specific tasks and tools to use during their sections, but otherwise giving them no instructions.

Recollections of the ensuing event vary widely—thanks both to its spontaneity and to its seeming frivolity—so a precise accounting is impossible. But the performance went something like this: Cage, looking as ever like some sort of possessed Gothic minister, stood on top of a stepladder delivering lectures punctuated by long silences. Charles Olson read poetry on a different ladder. Robert Rauschenburg operated a windup phonograph with a horn speaker. Cunningham danced throughout the audience, at one point trailed by an uninvited barking dog. David Tudor played piano.

Though Cage proved himself willing to relinquish control over large parts of his art with Theater Piece No. 1—in the process inventing the countercultural form that would later be known as the “Happening”—he still felt he had not fully achieved the complete elimination of his artistic ego. But during the performance something in the room seemed to constitute the full break between art and artist that he had been attempting. From the dining hall’s rafters hung Rauschenberg’s now-famous all-white paintings, which he had completed at the college the year before. Cage was fascinated by the way they simply reflected the objective, natural world around them. “The white paintings were airports for the lights, shadows, and particles,” he later wrote. Cage realized that he wanted to achieve aurally what Rauschenberg’s paintings accomplished visually—what sort of natural phenomena might a completely silent composition reveal to the careful listener? Encountering the White Paintings series at Black Mountain, Cage said, brought him “the courage to take the path, come what may,” and finally compose a piece consisting solely of silence.

A few weeks after Theater Piece No. 1 (and just one week before his fortieth birthday), Cage debuted 4'33" at the Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, New York. Just as he had for his Black Mountain performance, Cage used chance operations to generate random lengths for the three sections of his piece. His pianist, Tudor, closed a piano lid to denote the beginning of each of the three sections, and he opened it to denote the closing—consulting a stopwatch to follow Cage’s precise timing of the score. During each section Tudor did nothing more than hold down a pedal.

Though Cage’s composition contained no musical notes, his performance was not silent. The audience could hear wind coming through the trees, rain blowing onto the roof, and even the breaths taken by others in the audience (not to mention their nervous laughter). “Other sounds could be heard, too, if one relaxed the mind and paid attention,” Cage’s friend, the dancer Carolyn Brown, recalled. But “most people didn’t and were angry, put out, and put off.”

Nevertheless, Cage felt that he had finally followed his project to completely sever art from the artist’s intention to its logical endpoint. He had created a conduit to give an audience the music that was already all around them. Almost two decades after Josef Albers promised to open eyes at Black Mountain, the college’s apostles were opening ears as well. “Music is continuous,” Cage concluded. “It is only we who turn away.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.