Oaxaca Wreck

By John T. Edge

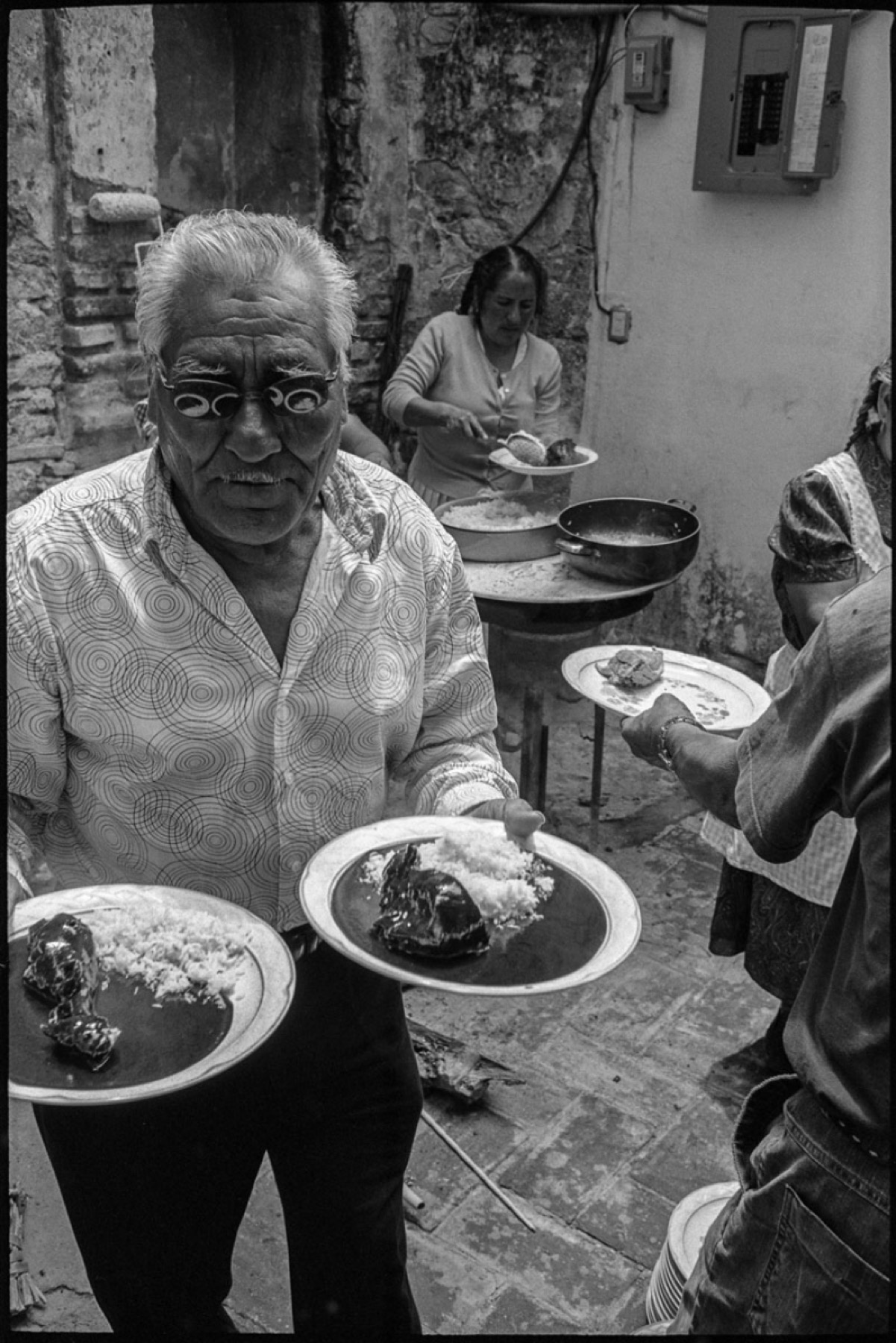

Photo of Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, by John Langmore

In May of last year, on a blacktop outside Athens, Georgia, a Chevy Tahoe struck my MINI Cooper head-on. Metal crumpled and flew through the air. I heard the poof of airbags, then nothing, then a hesitant affirmation. “You’re okay,” my friend Wright Thompson said, first to himself, and then to me. My left lung had collapsed. My left tibia was broken. Blood spilled down my neck. Ten minutes earlier, we had wrapped the first-episode shoot for our new television show, TrueSouth, in Athens. And then I was almost gone.

That wreck delivered me to a crossroads. Before that Tahoe hydroplaned across the centerline, I had not wholly embraced my hometown of Oxford or my place in it. Instead, I had traveled the South, the nation, the world, to write about food and drink. I told myself that I was trying to make sense of what unites and divides us. But my search was more personal than that. Plotted, the stories I told for this magazine and others revealed an unsuspected path.

I was backpedaling from a childhood pitched by violence, looking in restaurants and bars for places to belong. Over seven weeks of convalescence, in conversation with neighbors and friends who arrived nightly with coffee cake and whiskey and books, I recognized that my two-decade search to belong in restaurants and bars had really been a search for home.

That search had brought me home to Mississippi, and showed me new ways to belong in places like Oaxaca, Mexico. There, this past November, still hobbled but willing, I walked the streets for two days and nights before I became a regular at El Lechoncito de Oro, a late-night food cart fifty paces from our rental.

Seven waiters worked the street, wearing blue polos and blue mesh ball caps. Ballpoint pens tucked behind ears, order pads in back pockets, they wove between double-parked cars to deliver pork tacos and tortas and Cocas Mexicanas as a guitar-trumpet combo played a gutter bounce. At the center of the swarm, on a yellow curb at the corner of Calle de los Libres and Murgía, stood a stainless-steel trailer, strung with LED beads and framed by a banner portrait of a happy pink pig in a white chef toque, a red scarf tied around his neck. The text translated as the Golden Piglet. Taquitos were seventy-five cents, tortas a buck and a quarter.

A television mounted under the trailer’s back eave broadcast a game show. A cooler, stashed next to the trailer hitch, brimmed with ice and glass soda bottles. Plumes of steam billowed from the flattop. The cook tapped out a rhythm with his spatula, alternately steaming tortillas and crisping chopped pork. Against the wall of a maroon masonry building, opposite the sad and understocked store my wife, Blair, and our two friends came to call the gulag grocery, slurry-voiced couples linked arms and stared up toward the lights of the cart. Three young men pulled a bench from a nearby truck, makeshifted a table out of a water jug, and balanced a bottle of salsa verde on top.

I had passed the same spot again and again, cell phone in hand, Evernote app loaded with the places I was supposed to go. With touts from chefs and writers, I mapped coordinates and ate second dinners. And then each morning, I marveled at the grease stains that splotched the empty asphalt patch where that cart had parked the night before, recalling the scene that swirled there, and then plunged forward, fixed on checking another box. Three days into our trip, I stopped my search and, for the first time, saw and tasted the bounty just beyond my doorstep.

Calamity and travel arrest time. They beg focus and feed insights. Tourism has taken on some of the functions that religion once served. Here in America, we have ritualized restaurant going, embracing time at table as a cultural passkey, just as we previously codified sightseeing and museum going. Each effort shows respect for (and belief in) a society, a community, a place.

“Travel helps me arrange my furniture better.” That’s how my friend Joe Stinchcomb, a bartender in Oxford, put it. At about the same time I hit the road to film TrueSouth, he had traveled to Germany and Belgium and returned to Mississippi with a new way to see what’s before him and how the pieces of his life fit together. In conversation with Joe, I recognized that travel has given me license to appreciate and memorialize a moment.

Five years back, I recruited the author George Singleton to give a talk at a Southern Foodways Alliance event in the Mississippi Delta. One night, we drove out to Po’ Monkey’s, a tin-roofed juke in the middle of a picked-over cotton field, near the town of Merigold. Everyone got two tickets for drinks and one ticket for admission.

Before we left, I saw George out front, talking to owner Willie Seaberry, a wiry man chewing on a short cigar, said to run the last true juke in Bolivar County. The next morning, George showed me how he’d memorialized that moment. Po Monkey, Seaberry had scrawled in a tight black script on a tear-away ticket. To this day, George keeps that small ticket, inscribed with that tight black script, in his wallet. On my best days, that’s what I attempt with my writing.

Hacked into bits, tossed with crisped pork skin, stacked on a flattop to keep warm, covered with a thin film of plastic wrap, roast pork from the Golden Piglet tasted sweet and clean. Like a fresh link of boudin, pulled from a countertop crock-pot in a Cajun Country gas station and cut open with a pocketknife. Rolled in small corn tortillas, brightened with a vinegary salsa verde, their taquito recalled a chopped whole hog tray, served with a cornbread flat at a barbecue joint on the eastern flank of North Carolina.

That pork tasted like home. That is to say, it reminded me of a number of the restaurant and bar homes I have claimed in the South. Traveling the city, much begged comparison. On a daytime taxi ride, I saw trees with white rings painted around their trunks in a style I remembered from my childhood. Two nights in a row, anthem rock that would have played well at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium boomed from a hillside amphitheater. At a bar called El Destilado, I drank white whiskey made with local black corn. From a vendor who worked the zócalo in a bright white guayabera, I bought homemade peanut brittle, flecked with sesame seeds.

That pork also tasted like Oaxaca, where ersatz cotton bolls bloom in pochote trees, ceramic monkeys hang from wrought iron–fronted windows, and vendors pedal the streets each morning, crooning “tamales, tamales, tamales” into trucker mics hooked to bullhorn speakers. On vacation, I connected the thrill I get when I see or taste or hear something for the first time to what I gained after my wreck in Georgia, when the scales dropped from my eyes. I relearned how to regard a place, a person, a moment, a taste.

I ate with intent, memorizing the nuts and chiles in salsa macha, marking the variances between mole rojo and mole negro. I learned to taste the difference between a tortilla cooked on a gas-fired flattop and a tortilla cooked on a wood-burning comal. I listened more closely, too, falling asleep to the dogs that barked in the alley that bordered our rental, imagining what they looked like, and waking to the singsong of children practicing lessons in a nearby schoolyard, while I tried to recognize whether they were reciting math tables or conjugating verbs.

On day four, I pulled up short of a cafeteria-style restaurant to watch a woman in silhouette, her outstretched hands patting balls of masa into tortillas with the grace and precision of a liturgical rite. Offered a seat in the center of the dining room, I asked to sit near the stove where she worked. Instead of trying to take a picture, I sipped an Americano and watched. Two nights later, my wife and our two friends stared down into a gutter outside our rental house, watching a trail of ants carry off cracker bits or chip shards in a jumpy line that warped along pavement cracks, crossed bridges made of twigs, and bent around pebbles into cul-de-sacs. No, we were not stoned.

Each morning, I stepped in a new restaurant to take a look, hoping to find a place Blair might like for lunch. The ground floors were often cramped and unloved. But when I spied a staircase and climbed, I would land in a tile-floored room, open windows facing the street. At La Olla, a bright oversized mural of a mother and father stretched across the far wall, and a tree bloomed through the window. At Café Lavoe, a corner bar opposite the botanical gardens, I entered through a cobblestone tunnel and climbed to a rooftop vista that recalled turn-of-the-last-century Montmartre. Regard your surroundings, plunge forward—that seemed the lesson.

That gift of new sight was, by then, familiar. I had gained it in the wake of our wreck. And I had gained it on other trips. In Vietnam a decade back, an acquaintance and I busted loose from an organized tour, bought a six-pack of warm beer, and flagged a taxi south. We ran a gauntlet of swerving trucks, past thatches of tapioca drying on the roadside, Vietcong cemeteries that sprawled the hillsides, and billboards that warned of unexploded ordnance. An hour and a half beyond Hue, we hit a beach town in the DMZ, where dozens of longboats lined the shore. Hand-carved hammers and sickles, symbols of the Communist Party, jutted from their prows. A man walked up. In his outstretched hands he held a fiberglass liner for a U.S.-issue army helmet. Two cuttlefish and a half dozen crabs flopped and wriggled inside. On the beach, a young woman set up a plastic table, plastic chairs, and a bucket of cold beer. As the surf crashed, she cooked for us on a camp stove.

The cuttlefish was chewy, but the crabs were sweet. Standing in a tidal eddy, looking down the coastline, I thought about how American presence and money can change a place and a people. I saw the sustained might of communism on display there. And I saw the allure of capitalism. I glimpsed economic change in real time.

After our wreck, I pledged to carry forward the thankfulness that buoyed me in the first weeks of my recovery. But like many a convert to a cause, from sobriety to self-awareness, to claim my new stance I had to fight off old anxieties and habits that had crept in on tiptoe. Two months passed before Wright and I were well enough to make more TV shows. When we went back on the road in July, I left home wondering if the scales had fallen for good.

For each episode of TrueSouth, Wright and I claimed two restaurants in two towns as our homes, regarded the places and the people intimately, lovingly, and then wove a narrative that exposed the tensions and the promises of each. We made homes in Birmingham, among the descendants of Greek immigrants who quit their villages by the Aegean to make new lives and work new jobs in the coal camps and iron furnaces of Alabama. We sat with a steam table café owner in Nashville who cried unashamedly as she spoke of her love for her customers and her need to serve them. And we talked about what places we might claim once we got back home to Oxford.

When I moved to Mississippi in 1995, I became a quick regular at Bottletree Bakery, just off the square, across from the church that my family would subsequently join. At that low counter, with a thick china mug in hand, I ate scones pocked with crystallized nuggets of ginger and pored over grad school texts. I befriended the charming misfits and dreamers who poured refills and stared at their shoes and beamed guileless smiles. And then I quit the place. Because I got jaded. Because I got busy.

Since I recommitted to Bottletree in December of this past year, I’ve eaten a damn good biscuit stuffed with hand-patted sausage, while a beagle puppy flopped across the floor. I’ve spent a lazy morning staring at the rainbow of folk art that owner Cynthia Gerlach collected as a graduate student. And I’ve marveled at how, when I ordered a butter-glossed croissant, the kids behind the counter served it, absurdly, with a couple of foil-wrapped butter pats. I’ve watched a young stoner couple cuddle. I’ve eavesdropped on the regulars who gather at the window table. I’ve compared the place to a hot mess. I’ve compared the place to a lyceum. And I’ve settled back in.

A few days back, I ran into a friend in the bathroom of a local bar. We know each other in that obscure but real way that folks who nod to each other on the street in a small town do. He asked me where I had been. I told him about the beagle. He knew the backstory of the dog, how an employee had adopted it, and so had the café. I realized that if I didn’t live in Oxford, I would clamor for Bottletree. I would valorize the people who work there. I would celebrate the community that gathers there. And now, returned from travels real and metaphorical, having tasted near death and new life and very good pork tacos, I do.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.