A Long Yarn

By William Browning

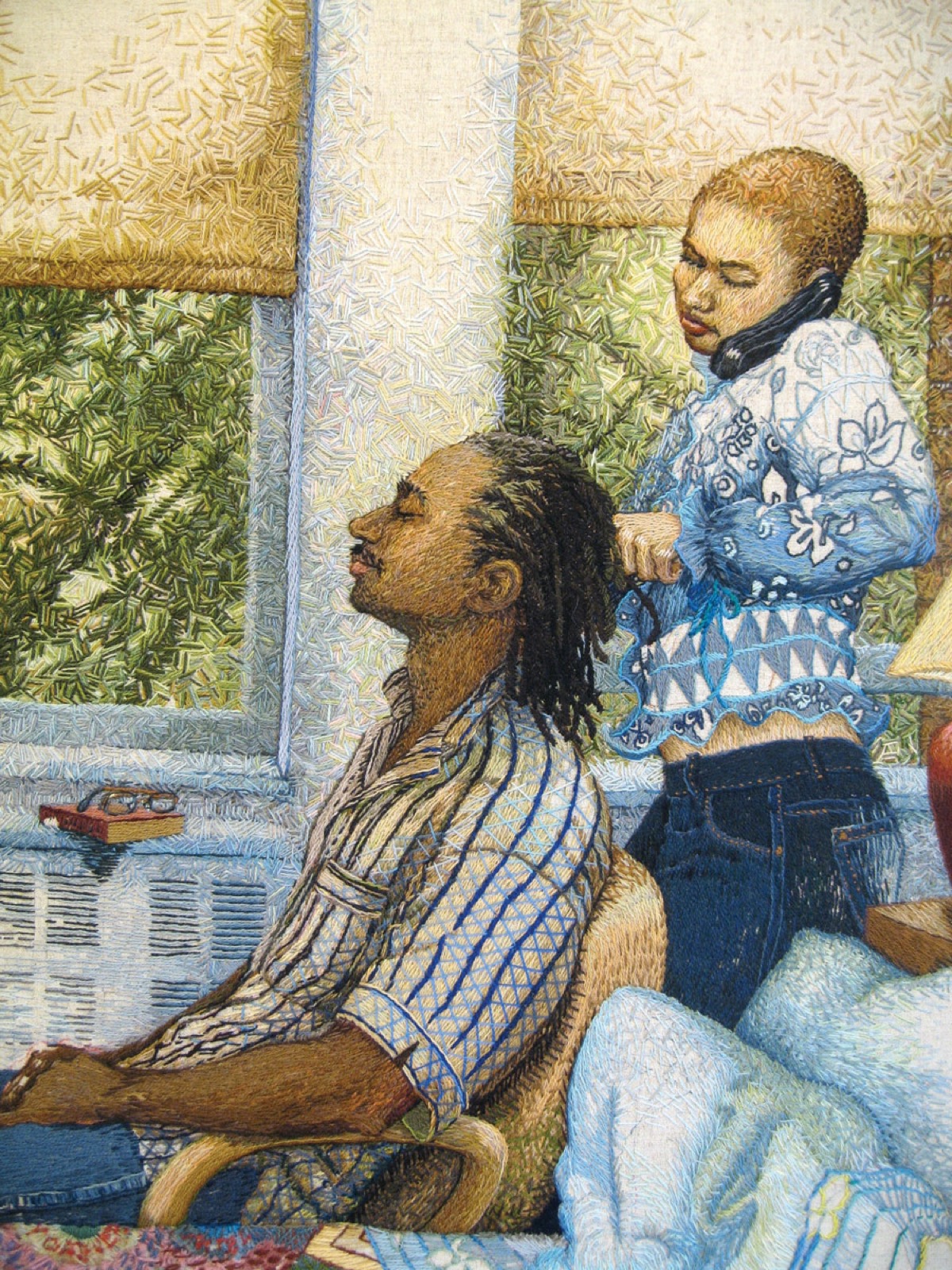

“Flower” (2003), ©Ruth Miller. 66 x 42 inches, hand-embroidered wool on jute, RuthMillerEmbriodery.com

An artwork by Ruth Miller consists of dozens of strands of colored yarn intricately stitched through stretched canvas, the support medium. A close inspection reveals that no strand ever acts alone, as a border or line or color. Miller, while making hundreds of thousands of stitches, blends and layers and twists the strings in order to marry their hues, establish her figures, and settle depths. This approach, of stitching different strands of colored yarn through canvas so many times that the individual strings join in a subtle and collective harmony, leads to an image made of rigorous yet soft details. Nothing is exact but everything is defined. The result is a portrait—Miller’s work is almost exclusively portraits—that from across a room is startlingly realistic and that up close, near the strands, can feel alive and uncomfortably intimate, like being so near someone’s personal affairs that fears and failures are sensed. The voyeurism of it may be why she promises to not reveal a subject’s name. Even so, Miller’s portraits, which she calls “reality-based visual narratives,” always have an undercurrent of hope, a theme reflected in titles like “Our Lady of Unassailable Well-being” and “The Impossible Dream is the Gateway to Self-Love.”

For most of the last decade Miller has worked alone in her studio, on the east end of her home in Catahoula, Mississippi, near the Gulf Coast. There are windows on three sides. “When I’m working,” she said, “I need sunlight to make the best decisions.” Plastic containers full of rolls of Paternayan wool yarn, which she favors for its durability, are stacked to the ceiling. A daybed is nearby. Miller often writes notes, reminders, and declarations to herself, and she has positioned them around her studio—“Write a journal of this experience (or forever),” “Don’t be overly available,” “SOTHEBY’S,” and “Make art.” There is also, tacked in one spot, a photograph of the actor Samuel L. Jackson, with whom she feels a kinship.

Miller is seventy. Her pieces hang on the walls of Mississippi museums and New York City art galleries, sell for tens of thousands of dollars, and have recently brought her critical acclaim—in February, she received Mississippi’s prestigious Governor’s Arts Award for Excellence in Visual Arts. You would never know, from here, that for most of her life a crippling shyness kept her from pursuing her artistic goals. The photograph she has of Jackson—it is actually the cover from a 2015 issue of New York magazine—shows him looking across a table, directly into the camera, with a gaze that Miller interprets as, “What is your excuse?” The image acts as an encouraging reminder. Miller has worked on drawings and embroideries and other forms for as long as she can remember, honing a talent that became evident in childhood. She had passed fifty, though, by the time she decided to pursue what she long wanted: to be a professional artist. “I thought it was too hard,” she said, “to walk around and talk to people to get galleries to like my art and me.”

A hallmark of a Miller piece is the way she can capture someone’s core in the smallest of gestures or mannerisms. The bulge of a man’s shoulder, just visible in a shirt’s wrinkle, suggests his resolve. A woman’s closed-eyed grin, in profile against a blue sky, shows her contentedness. This ability is something her sister, the dancer and choreographer Bebe Miller, attributes to an exhausting interior life: decades of reticence and self-examination have made Ruth Miller attuned to the complexities of others. The irony is that for most of her life Miller felt at a deep remove in most company. She creates portraits, in part, because doing so gives her a chance to explore the motivations of people. “I always wanted to know why they do what they do,” she said on a Mississippi Arts Commission podcast earlier this year. “How they feel about life. How life affects them. And I think portraits give me a chance to not only investigate that, but they’re easy for other people to latch on to the narrative with.” These narratives are another hallmark of Miller’s art, and they often spring from experiences in her own life.

A piece titled “Teacup Fishing” depicts a woman, in a boat with no oars, reading a magazine while the line of her fishing pole is submerged, not in the water surrounding her, but in a teacup in the bottom of the boat. Over her shoulder, the sun sets. While visiting Miller in her studio once I mentioned that it seemed the woman was so engrossed in reading that her fishing line had dropped by accident into the teacup. Miller corrected me. The woman had intentionally put her line in the cup, she said, because “that’s all she is asking from life,” meaning the woman was thinking too small and did not know she was adrift with time running out. Miller often makes philosophical statements in casual conversation. While we discussed “Teacup Fishing,” she said, “In the midst of life, especially as you get older, you see the finiteness of life.” She told me the scene came to her in a vision.

Miller is tall and graceful. Her age comes through her eyes, which are wise, but nowhere else is it evident. She can be elusive in conversation, in a charming way, as when I asked, “What year did your aunt die?” and she answered, “I forget that always, right away, because it’s not something I like. Even my mother, I don’t remember what year. I don’t want to know. Let me think. It’s been about three years.”

She was born in New York City and spent most of her life there. Her mother, Hazel Clark, moved to New York from Meridian, Mississippi, in the late 1930s for opportunities not available to African Americans in the segregated South. She became a nurse and teacher and married St. Clair Miller, a sailor from Barbados. They had three children. They lived in the Bronx, then Brooklyn, later Queens. Clark seems to have been the first to notice her oldest daughter’s interest in art. There was never much money, but she filled the family’s home with art supplies and often arranged visits to museums and theaters.

Ruth Miller wonders today if her insecurities are the result of a prior life, when she was an artist who relied on patrons, and gaining their support required navigating dangerous political landscapes and complex social situations that left her carrying anxieties through subsequent lives. The anxieties came early in this life, mostly as a sense of foreboding. Miller began avoiding people in elementary school. “Social situations were landmines,” she said. She found confidence in drawing. A black-and-white picture from the mid-1950s shows Ruth, maybe seven or eight years old, sitting on a rock beside a lake in Maine, where her mother had a summer job as a nurse. She is drawing with pencil and paper and tilting her head in blissful concentration. Bebe Miller, who keeps the picture, said it captures her sister’s ability “to lose herself in her work and the dream of it and wish of it.” Another place Ruth Miller felt at ease was in time spent with her aunt, Mildred Clark Carr, her mother’s sister, who lived with the family. Carr showed Miller how to embroider, simple decorative stitching like daisies on tablecloths. Even now, working with yarn brings her serenity. “That feeling rises up immediately whenever I sit down,” she said. “I’m at home.”

Hazel Clark encouraged Ruth to apply to the High School of Music and Arts in Manhattan (now LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, the school that inspired the movies and TV show Fame). She was admitted, in part, on the basis of drawings she submitted. Miller graduated in 1966. The following year she and her mother rode a bus to Montreal to attend the world’s fair, Expo 67. While walking through the African pavilion, Miller discovered the woven tapestries of the late Papa Ibra Tall, a Senegal-born artist who had studied in Paris and of whom Duke Ellington once wrote, “It is impossible to miss the feeling of Old Africa in each and every stroke of his work.” Until then Miller had encountered tapestries only in New York City museums. They were massive, likely made by groups of people, for the purpose, she said, of “keeping people in cold European castles warm.” Tall’s were different. They were small enough to hang on an apartment’s wall and embraced bold colors. Miller, who continued to love drawing but never enjoyed paint as a medium, left Montreal inspired. “A light went on” is how she described the experience. “I could use my clean, dry, soft embroidery and still come up with a painterly effect!”

By then Miller was a student at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private college in the East Village, founded in the nineteenth century by industrialist Peter Cooper, who felt higher education should be available to everyone. Her drawings helped gain her admittance into the school’s fine arts program. After less than two years, she bowed to her insecurities and quit. It was 1968. Miller, living in Queens with her recently divorced mother, entered into what she described as an “extended adolescence” that lasted until the mid-1970s, when her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Hazel Clark, still in her fifties, died shortly thereafter. She left a little money that Miller used to purchase a home in Catahoula, where a relative said several houses were going up for auction following foreclosures. Some of Miller’s other relatives, from New York City and Mississippi, were moving to the area, and Miller decided to join them. “I felt that here was a place that I could be at home,” she said of Mississippi, “that my soul could be at rest.” She relocated in 1975. The move was not the fresh start she envisioned. Miller floundered in the absence of her mother. She also found that the social dynamics in the small community were hard for someone coming from a bustling, impersonal city to grasp. After five years of an aimless sort of life, Miller moved back to New York City. She held on to the house, though.

The next two decades were difficult for Miller, and she does not like sharing specific details from that time. She never stopped making art—black-and-white sketches, small embroidery pieces—but she was a single mother with three children and did not have a lot of money. For about a year, she and her children squatted in a building on the Lower East Side and the only income for a spell was what she earned from selling earrings she had made. Eventually, Miller secured an apartment in Harlem and in 1995, with a friend’s help, found work as a carrier with the U.S. Postal Service, delivering mail in Greenwich Village. The job brought financial security. It also brought long days walking in the elements, sometimes a six-day work week, and the occasional hostile exchange with the public. After five years, Miller sensed a hardening of her disposition. “I knew there would be no chance of being an artist,” she said, “if I continued to get hard. It’s the wrong kind of head. You can’t let anything in.” Being an artist, she decided, could not be more difficult than delivering mail.

In the fall of 2000, several months after her youngest child graduated from high school, Miller quit the Postal Service, intent on becoming a professional Artist—“capital letter,” she said. In making the decision she had two goals. One, leave her insecurities behind and grow as a person. Two, validate her late mother’s faith in her. “I feel like art is my tool for transformation,” she said. She was fifty-one years old.

“Blue Peace” (2007), © Ruth Miller. 37 x 25 inches, hand-embroidered wool on jute-cotton blend fabric, RuthMillerEmbroidery.com

“Blue Peace” (2007), © Ruth Miller. 37 x 25 inches, hand-embroidered wool on jute-cotton blend fabric, RuthMillerEmbroidery.com

Each Miller piece follows, from conception to completion, a similar journey. “Most times I start with an idea,” she said. Then she needs someone to physically embody the idea. “I look to try and find, say, not just a pose I’d like someone to be in. But there’s an issue that comes up, and I think maybe a certain pose will illustrate the issue.” Because she remains shy, Miller often uses family members and friends as models. After taking a series of photographs with a Canon 35mm and identifying the one that best encapsulates what she wants to say, she creates a series of line drawings with a No. 2 pencil and, because she likes the smooth surface, “the whitest computer paper I can find,” she said. (She has used quality drawing paper, but the fine texture upsets her concentration, leading, she said, to drawings that are “stilted or awkward.”) The goal of the line drawing is to capture the person’s figure in the simplest manner. When this is achieved, she makes several copies. On one she toys with shading. On another she uses colored pencils to explore which colors might work best. On another she draws over the image a grid (of squares an inch or so on each side) to guide her transfer of the drawing onto a similarly gridded stretched canvas. (Miller learned this transfer technique at Cooper Union.) Then she reaches for needle and yarn, and intuition enters the process. The drawings provide a guide for colors, but the right combinations are revealed only through stitching. It is laborious and slow, and mistakes are frequent. “You have to realize,” she said, “that each one of these is not a straightforward process. It’s a doing, it’s an undoing, it’s a doing, it’s an undoing, all through the whole process.” Tweezers are the tool for undoing. It takes Miller, on average, one year to finish a single piece. Elizabeth Abston, curator of American art at the Mississippi Museum of Art, described Miller’s method as an “almost meditative process.”

After leaving the Postal Service, Miller was too self-conscious to ask anyone to pose for photographs, which would have required her to announce herself as an artist, a title she felt she had not earned. So she began with a self-portrait. Her sister photographed her. While looking at the subsequent images, Miller noticed a piece of clothing hanging in a way that resembled a rose petal. “It occurred to me,” she later wrote about the painting for an exhibition, “that flowers don’t suffer from lack of self-esteem. They simply are . . . each one is an equally wonderful manifestation of the Divine.” Nineteen months later she finished “Flower,” the only self-portrait she has done. In it, Miller, surrounded by large green petals, is sitting with resignation across her face. Abston believes the piece’s power is found in the way it portrays Miller working through an honest examination of herself. The bloom suggests self-realization. It is the largest piece she has ever made—three and a half feet wide, five and a half feet tall. “It was a test,” she later explained, “to see if I was up to the challenge.”

For the next several years, working mostly on the wooden floor of her Harlem apartment, Miller produced six or seven pieces. (“I guess I don’t keep track of it because that’s like another pressure,” she said.) In 2007, she took part in the Harlem Open Artist Studio Tour, a Harlem-wide studio crawl, inviting people into her apartment to view her work. Among the visitors were Karen and Sharon Mackey, owners of Mackey Twins Art Gallery in Mount Vernon, New York. They saw “Teacup Fishing,” which, at the time, was a work-in-progress, and were “spellbound by it,” Karen Mackey said. “It was breathtaking. It was haunting.” Soon thereafter the Mackeys began hanging Miller’s work in their gallery, something they still do. The Mackey sisters view Miller’s pieces as an extension of her personality, which Karen Mackey described as “warm, shy, smart, unassuming, very pure, very genuine.” Another visitor was C.C.H. Pounder, the Emmy-nominated actress best known for her work on NCIS: New Orleans and The Shield. Pounder remembers entering Miller’s space and thinking that the vivid and fluid colors reminded her of Vincent Van Gogh’s painting. She was “shocked,” she said, to discover that it was embroidery work. An avid art collector, Pounder subsequently bought two of Miller’s pieces. She also offered her a solo show at Pounder-Kone Art Space, her Los Angeles gallery. Pounder suggested that she would need at least ten pieces. Miller did not have ten pieces she wanted to exhibit. The solution she came up with was a seemingly dramatic one: Move back to Mississippi, where she could live rent-free in the home she owned in Catahoula, devote herself to her work, and then mount her show. “I never make long-range plans,” Miller said. “Then—boom—I’m going to do this thing.” Miller had no car. She bought a Chevrolet Lumina for $900, loaded it with her yarn and other supplies, and left the city, in April 2009, once again for Catahoula.

Miller’s second move to Mississippi did not begin well. In her absence squatters had moved in and left the house in bad shape. The roof and toilet needed repairing. To help pay for expenses, Miller worked at Walmart and for the U.S. Census. In 2011, when she turned sixty-two, she began taking Social Security, allowing her primary focus to return to embroidery portraits. By then Pounder had moved to Canada and closed her L.A. gallery, so Miller’s planned solo show fell through, something Pounder, who remains supportive, still regrets. “I didn’t at the time realize the intensity and detail required in her work,” she said. Miller did not let the news distract her from her goal of using art to grow and transform. “I was going to try,” she said. “More than try—I was going to do it.” She embraced the solitude of Catahoula, a rural place where the roads are barely wide enough for two cars and chickens roam a public park, and began creating her pieces. I think of Bebe Miller telling me her mother passed to each of her children a “quiet determination.”

In the last decade Miller has completed nine pieces. In 2014, several of Miller’s pieces were chosen for the Mississippi Museum of Art’s Invitational, an exhibition held every two years. That led to “Flower” being included in Picturing Mississippi, a 2017 exhibition in celebration of the state’s two-hundredth birthday. The following year, Abston nominated Miller for the Mississippi Governor’s Arts Award. “Her attention to the power of line drawing is evident in her work,” she wrote in the nomination letter, “with carefully planned compositions that begin to take on lives of their own once her process begins.” Miller also received a Mississippi Arts Commission grant, which led to a close-up of her work being featured briefly on a Mississippi Public Broadcasting commercial. Kevin O’Brien, the director of the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi, happened to see the commercial and was struck by the detail he saw. “There was just some sort of magical look to it,” he said. When he found out Miller lived in Catahoula, forty-five or so miles from Biloxi, he offered her a solo show at the Ohr-O’Keefe. The show, on display during the summer of 2017, was called Thinking Art into Being: Ruth Miller’s Contemporary Embroidery and featured eight pieces, six of which Miller had created since moving back to Catahoula. Beside each one was a short essay, written by Miller, that explained her process, as well as her themes.

Of the piece “The Impossible Dream is the Gateway to Self-Love,” she wrote: “Once we stop looking to others for approval, we’re on our way toward self-acceptance.”

About “Our Lady of Unassailable Well-being,” she wrote: “We can carry our halos with us and put them on when we need them most.”

And of “Teacup Fishing,” she wrote: “What has hampered me most in the past is the tendency to ask too little from life. With this portrait, I show myself and others similarly afflicted how foolish this is. Blessings are all around us. We need only ask. How do we ask? By coming to a decision about what we want and refusing to be distracted from it. Once focussed, life tends to show us the next steps until we arrive at our goal.”

I first visited Miller during the summer of 2018, as it happens, a few days after she learned that she would receive the Governor’s Arts Award. Although she was pleased with that honor, there was a slump in her shoulders. She spoke mostly about impediments to her work, like the trees around her home, which had grown so tall that sunlight was failing to fully illuminate her studio. And she said that the engagements that always follow recognition, like interviews and talks and ceremonies, had served to remove her, literally and figuratively, from her work space. Miller said she felt like the move back to Mississippi, while enabling her to focus on her art and grow as a person, had isolated her too much. “I don’t mind so much living alone,” she said, “I’ve just lost all the rest of my life.” (While one cousin still lives nearby, everyone else from her family is gone. One of her daughters lives in Florida, another in New York, and her son is a long-haul trucker.) Though she struggled to pinpoint the exact source of what she was feeling, it seemed to result in a decline in inspiration, and at one point she said, “Something is dying.”

Several months later Miller delivered a keynote address at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts in Tennessee. After describing the circumstances of her move back to Mississippi, she said: “Now, after nine years, I realize that that approach—while good for production—was a form of violence to the self.” She closed by encouraging attendees to care for themselves.

After that initial trip to Miller’s home and studio, when a malaise had found her, I continued, over the course of several months, to visit her. Soon enough she seemed to rebound, or at least become more willing to work through the funk. She took a saw to the trees outside her studio. (She also purchased some LED lights for the studio’s ceiling.) One day she showed me a work-in-progress—a portrait of a dancer—and I noticed two blank canvases perched in a nearby chair. When I asked about them, Miller explained her plans. One was to be a portrait of a woman applying lipstick. The other, she said, might be the beginnings of something she had been pondering. When Miller’s aunt—Mildred Clark Carr, who had taught her embroidery—died a few years ago, Miller inherited an album of old black-and-white photographs, which show thin old men with proud, straight backs, and smiling, rural women in Sunday dresses. These are her Mississippi ancestors, from the early decades of the twentieth century, who lived through the times Hazel Clark left behind when she moved to New York. Miller wants to create portraits of them, a series whose narrative would tell stories of perseverance.

One evening in early May, Miller called me unexpectedly and said she had finally figured out what she meant when she told me, months earlier, that something was dying. I had been pacing my porch while we chatted but at this I stopped to hear what she would say. “I have decided,” she said, “to see if I can just be and be happy.” When I pressed her about what this meant, she said, “I want to see if I can engage in life and just be happy with what life is.” I asked if she was going to continue to make her art. After a brief pause she said she had always made art and would always do so.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.