Talking Drums

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

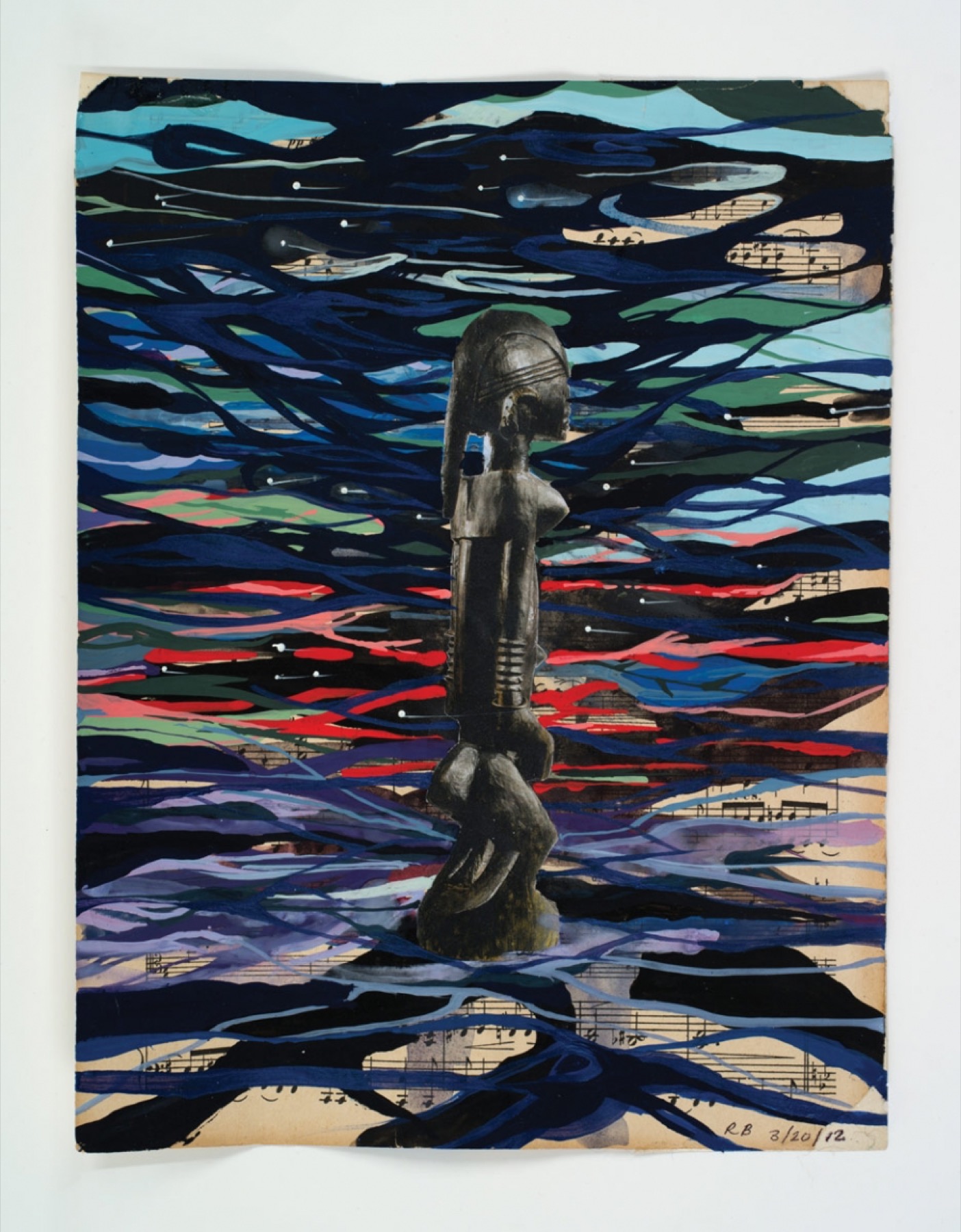

“Notes from Tervuren” (2012). © Radcliffe Bailey. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

I

n two and a half years’ time, between the spring of 1738 and the late fall of ’40, South Carolina endured two plagues—the first of smallpox, the second of yellow fever—and a Great Fire (“one of the worst in any city during the colonial period,” according to the scholar who has made the most careful study of the matter). But of the catastrophes that marked those months, none of these three was fated to leave the most lasting scar on the mind of the colony. There was a fourth, a slave revolt, small in scale, but growing when it was terminated, and unsettlingly bold. Also influential—its ripple effects make it probably the most important such revolt in Southern history. It happened right as the second epidemic was peaking, in September of 1739, and may have been timed to take advantage of the shaken condition in which the two years of disease had left the colonists. Historians call it the Stono Rebellion, but on the Southern Frontier they knew it as the Gullah War, or more plainly as the Insurrection of the Carolina Negroes.

We call it the Stono Rebellion because it started in a plantation district (a “general area of settlement,” in one scholar’s suitably vague phrase) known as Stono, which had taken its name from the river that ran near it, the Stono River, which had taken its name from a Native American tribe, the Stono or Stonoe or Stonowe, who when Carolina was founded in 1663 were settled close to Charles Town. By one of those dark coincidences history delights in, the Stono themselves are remembered principally (almost entirely) for having started an uprising against the colony. Like the rest of the coastal tribes that the Carolinians encountered, the Stono had quickly learned to resent white encroachment on their land and the serial abuses of the “Indian traders.” As early as the mid-1680s, the colonial authorities had begun to relocate the Stono onto a succession of reservations in order to make room for the expanding plantations, a process of “removal” that began earlier than most Americans realize and ended in the Trail of Tears. In 1674, the council was “credibly informed that the Indian Stonoe Casseca [cacique] hath endeavored to confederate certaine other Indians to murder some of the English nation & to raise in Rebellion agt. this Settlem[en]t.” And sure enough, not long after (according to the first historian of Carolina, Alexander Hewatt), “the Indians, from Stono, came down in straggling parties, and plundered the plantations.” This brought about a small war, the second Carolina Indian war (there had already been an earlier one, in 1666, up in the Cape Fear country). The governor, Joseph West, in order to “encourage and reward such of the colonists as would take to the field” against the tribe and its allies, promised to purchase, at a fixed price, “every Indian [whom] settlers should take prisoner.” These “captive savages” were then given to the traders, who “sent them to the West Indies, and there sold them.” For rum. The last time the word Stono, as applied to the tribe, appears in the colonial records is 1707. Their name passed to a river and an island and a ferry and a cluster of land holdings, but the people who had borne it were lost.

In 1739, an enslaved Angolan man named Jemmy was living on one of those plantations. That was the word the Carolinians used—Angolan—though the historian John K. Thornton has demonstrated that he was probably Congolese. As for his name, the primary sources give it as Jemmy, a not uncommon slave name, but in African-American oral history he comes down as Cato, and the revolt he organized as Cato’s Conspiracy. If his name was Cato, that may likewise have been a slave name. The slave owners thought it was clever to bestow classical names that way. Or he may have belonged at that time to the Cater clan, who had a plantation in the district, and whose name was sometimes spelled “Cato” or “Catow.” If he was a man called Jemmy, owned by the Caters, i.e., Jemmy Cato, that would reconcile the two traditions. We will call him Cato out of respect for the African-American tradition to which he most deeply belongs. Whatever we call him, he possessed another, African name, which we cannot know. He has been described (by the social historian Lerone Bennett Jr., in the Negro Digest, 1966) as the “first Negro leader to emerge with any clarity from the anonymity of the masses.”

In Africa, before his enslavement, Cato may have acquired military training. He was likely literate, and would have spoken Portuguese. Some Angolans and Congolese had acquired this language, an anonymous Carolina correspondent explained, “by reason that the Portuguese have considerable settlements and the Jesuits have a mission and school in that kingdom.” By the same token, “many thousands of the Negroes profess the Roman Catholic religion.” That number probably included Cato. There you had the paramount bogeyman of the Southern Frontier: not any one nation but the combined trans-Catholic threat of Spain and France, both of which had settlements bordering on or uncomfortably near to Carolina and Georgia. Indeed, the correspondent added—not quite accurately, perhaps, but tellingly—that the Portuguese language “is as near Spanish as Scotch is to English.” The only thing that scared the Carolinians as much as the Catholics were the colony’s so-called “domestic Enemies,” the blacks, who outnumbered the whites by the staggering margin of thirty-five thousand to nine thousand.

Fears of a slave uprising were rife in 1739. Earlier that year, in February, a man named William Stephens, the secretary to the trustees in Georgia (and a former Tory MP from the Isle of Wight who had been financially “ruined by extravagance” and accepted a place in the colonies), had written of rumors “that a Conspiracy was formed by the Negroes in Carolina.” He added that “the Rising was to be universal; whereupon the whole Province were all upon their Guard.” Those particular plans for revolt were uncovered before they could be put into motion, but there remained an increasing tension. And then in July, King George II announced the commencement of hostilities against the Spanish. The two nations would soon be officially at war. As the independent scholar Joel Berson proved, word of this development may have reached the slaves in the Stono area on the 8th of September, the day before they rose. Perhaps they were fired by it.

Stono was a “rebellion,” but it was also an escape. The Spanish had recently issued a proclamation promising freedom and land to any English slave who could get to Florida. Really it had been one in a series of almost identical proclamations. The Spanish were fond of that trick. They liked to tempt away the Carolina slaves, mainly as a way of messing with the English. Every so often, blacks did make it across the line. In 1738 an unusually large number had done so—seventy total, in two groups. The Spanish colonial authorities in St. Augustine decided to give them their own town and fort, north of the city, Fort Mose (Mow-zay). It lasted for about twenty-five years. Decades of heroic archaeological work have recovered Fort Mose from the swampland, and you can visit it today as a historical site. Most of the newly arrived blacks in Florida were sent to live there. In the event of an English invasion from the north, they would serve as a wall of defense. Who would fight harder against any incoming forces from Carolina than those who had lately been property there?

Word of the existence of this town spread among the plantations. There was a refuge to the south, and Cato heard about it, probably by word of mouth, although the English believed (and may have been correct in suspecting) that shadowy “Spanish Emissaries” had been “strolling about Carolina” under “diverse Pretences,” spreading the good news about Fort Mose. In March, another, smaller group of slaves got away. This one comprised “four or five who were Cattel-Hunters.” They took their owners’ horses, killing one man in the process, and rode south. They had an Irish servant with them. They were pursued, but they “knew the Woods”—they were cowboys.1 They got away and “reached Augustine, one only being killed and another wounded by the Indians in their flight. They were received there with great honours, one of them had a Commission given to him” (i.e., he was made a commander at Fort Mose) “and a Coat faced with Velvet.”

The colonists were rattled, no doubt. When another group of slaves tried and failed to get away the next month, one of the men apprehended was hanged and his body “hung in chains,” at a place “in sight of all Negroes passing and repassing by Water.”

In early September, a triggering event: the Colonial Assembly declared an act requiring all men to bring their firearms to church on Sunday mornings. The authorities feared that the slaves would take advantage of those few hours of mass vulnerability to stage an insurrection. The new act was to go into effect toward the end of the month. Cato, who may indeed have been planning to act on a Sunday, knew that he had very little time before those weekly windows would be closed.

On the night of the eighth, a Saturday night, there was some kind of clandestine gathering. There were about twenty people there, most if not all of them Angolans or Congolese. Cato spoke—he is referred to in primary sources as the group’s “captain” and “King”—and the slaves finalized a strategy for the next day.

In the morning, while the whites were at church, they broke into a storehouse owned by a man named Hutchenson, killing and beheading two white men who were there guarding the place. The heads were left on the steps. They took guns and powder and ammunition and marched south.

Here should be mentioned, on the matter of how events unfolded in the first hour of the rebellion, a dissenting opinion held by one of the most recent scholars to write about Stono, Peter Charles Hoffer (an esteemed legal historian and the author of a previous book titled The Great New York Conspiracy of 1741, about a foiled slave revolt in New York City two years after Stono). Hoffer argues that there was less intention behind the slaves’ actions than has been assumed. In Hoffer’s view, the incident at the store was a burglary gone wrong. They had not been expecting to find the two white men there. After killing them, they had decided to run. “Had the slaves not killed the two whites,” Hoffer writes, “their raid might have gone undetected. Perhaps they would have gotten away with the break-in . . . ” This is an intriguing re-reading of Stono. Perhaps it did all fall out in a messier, more spontaneous fashion. A chronicler writing more than thirty years after the event remembered that the slaves who started the uprising had been part of a road-building crew, and that the rebellion “took its rise from the wantonness, and not oppression of our slaves, for too great a number had been very indiscreetly assembled and encamped together for several nights to do a large work on the public road with a slack inspection.” (This document is included in Mark M. Smith’s essential Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt.) Perhaps Hoffer and the 1770 source are both correct, and the rebellion was not at all what we think, but a panicked reaction by a team of enslaved laborers after an unplanned crime. The evidence is ambiguous.

Whether it started as an uprising or not, it became one on the march. The slaves moved quickly. As they crossed the plantations, they killed many people, some in horrific ways. More than twenty whites died, men, women, and children. The rebels also spared certain people, including a tavern keeper named Wallace, who was known as “a good man and kind to his slaves.”

When the rebels had gotten clear of their immediate neighborhood and were advancing south toward Georgia (the new English colony that had come into existence only seven years prior), they experienced a fatal stroke of bad timing. The lieutenant governor of South Carolina, William Bull, was out riding, returning home from official business. At about eleven in the morning he caught sight of the small slave army, strengthened now by recruits picked up en route. They had “increased every minute by new Negroes coming to them,” according to an account that ran the next month in the colonial newspapers, “so that they were above Sixty, some say a Hundred.” Bull immediately wheeled around. He “was pursued,” the same article says, but “with much difficulty escaped & raised the Countrey.”

A militia formed, and a detachment of armed whites set out on horseback after the rebels. The latter continued to push south. As they marched, they were “calling out Liberty.” They had “colours displayed and two drums beating.” But in the middle of the afternoon, when they had gone about twelve miles, they made a hard-to-fathom decision to stop. They “halted in a field.” The newspaper account says that many of them were drunk on “rum they had taken in the houses.” That may be true. They were free—they had “burnt all before them without opposition”—and wanted to celebrate. John K. Thornton speculated, in a 1991 essay in the American Historical Review, that they paused to conduct a ceremonial war dance related to African military traditions (arguing along the same lines, historian John E. Fleming had suggested, in a 1979 essay in the Negro History Bulletin, that the rising slaves were under the influence of a “conjurer’s potion”—maybe that was what they had been doing at the gathering the night before, making and drinking it). Whatever the case, they likely had in mind, in deciding to stop, that more slaves would have time to flock to them. In fact, the article says as much, describing how they “set to Dancing, Singing and beating Drums to draw more Negroes to them.” Perhaps some other blacks did hear the call and rush to join the rebellion. But by stopping, the rebels gave the whites time to catch up.

The blacks fought “boldly,” by the later admission of the colonial forces, killing an unknown number of militiamen (an anonymous report that circulated in newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic seems to put the figure at twenty). The fighting dragged on. A series of skirmishes lasted a week and covered thirty miles of terrain. A discrete moment from the slaughter survives, in an account written by an unknown Georgia ranger just a week after the rebellion. A black fighter, recognizing his owner among the white militiamen, “came up to his Master.” The white man “asked him if he wanted to kill him.” The black man “answered he did,” while in the same instant “Snapping a Pistoll at him.” But the gun “mist fire,” and the white man “shot him thro’ the Head.”

The rebels were exhausted and outgunned. The whites “charged them on foot,” and the last holdouts “were soon routed.” About twenty-five of the escaping slaves had died in the fighting. Survivors were summarily executed in the field, according to a short item that ran in the New-England Weekly Journal, “some shot, some hang’d, and some Gibbeted alive.” A handful slipped away and ran back to the plantations they had just fled, hoping that their absence had not yet been noticed, but these too “were there taken and shot.” Given that Cato is never mentioned again in the period documents, he seems to have been among those killed. Most of the dead had their heads cut off and stuck “upon Poles in the Path-way as a Terror to the other Slaves.”

An unknown number of the rebels did get away. At least one or two probably made it to Florida. Or they ran into the forest and became maroons. A few remained at large for three years or more. The colonists hunted them down, one by one. They were feared not only as individuals but as organizers or provocateurs. The South-Carolina Gazette in Charles Town—which for the most part was almost bizarrely silent about the uprising, doubtless not wishing to spawn imitators—reported the arrest of one man in December of 1742:

[O]ne of the Ringleaders of the last Negro Insurrection, (belonging to Mr. Honey Williamson) was lately seized in Catow Swamp, by two Negro Fellows than ran away from Mr. Grimke, who brought him to Stono, where he immediately was hang’d.

Thus it ended where it had begun, in Stono. But the memory lingered in South Carolina, especially among the enslaved. Memories of Cato’s Conspiracy almost certainly helped to inspire future insurrections. And then as time went by, the story passed into folk memory. In the 1930s, when the Federal Writers’ Project (under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration) sent hundreds of researchers out into the field to record the life stories of former slaves, one of the individuals interviewed was a man named George Cato, in Columbia, South Carolina. He claimed to be descended from the leader of the revolt. “My granddaddy and my daddy told me plenty about it,” the WPA worker quoted him as saying. “Commander Cato spoke for the crowd. He said . . . ‘We surrender but we is not whipped yet and we is not converted.’”

Stono is frequently called “forgotten,” but when we examine the historiography more closely, the picture turns out to be more complicated than that problematical word, or any one word, can capture. In many respects “forgotten” is precisely the wrong word to use. The uprising has for most of its history been strikingly unforgotten, but still somehow suppressed, pushed down in the mix of the American story. This strange half-oblivion lasted until 1966, the year in which Peter Wood’s Black Majority was published. That book contains the first true scholarly reckoning with Stono and is still in many ways unsurpassed. Prior to that—and beginning with that first history of Carolina, Alexander Hewatt’s of 1779—the rebellion was always mentioned, but referred to in a glancing way. Many white sources—textbooks and speeches—attempted to take agency away from the slaves, arguing that the rebellion had been stirred up by “some unprincipled white men in the employ of the Spaniards,” who had only been using the blacks. There is no evidence of this.

African-American writers have long mentioned Stono. W. E. B. Du Bois, in his 1903 classic The Souls of Black Folk, includes “Cato of Stono” in a list of those early slaves who, prior to 1750, still had “the fire of African freedom” in their blood, and who had once left “all the Americas in fear of insurrection.” But then Du Bois says no more. The revolt had been so violent, murderous, even gruesome. That made it tricky to hold up as an inspiring example. White abolitionist writers had tended for the same reason to name-check it and move on.

Yet the rebellion has always been impossible to ignore, on account of its influence. The year after Stono, and in direct response to it, South Carolina passed the “Act for the Better Ordering and Governing of Negroes and Other Slaves In This Province,” better known as the Slave Code of 1740. This was a crackdown, a newly severe set of laws (many of them adapted or else borrowed wholesale from the legal code of Barbados) designed to restrain the movement and personal freedoms of the colony’s slaves, forbidding social gatherings and “wanderings and meetings” between them. It was the model for the various codes that remained in effect across the South until the end of the Civil War. The historian Wesley O’Dell, in a 2012 essay in Southern Studies, wrote that “for some Southerners, Stono was the central event in the history of North American slavery since it had spurred the creation of a ‘fundamental’ and ‘time-honored code’ aimed at policing the slaves.” O’Dell mentions in a footnote that when the aborted Denmark Vesey uprising happened in Charleston in 1822—one of the other great slave revolts in our history, albeit one that was betrayed by a slave, and snuffed by the authorities in the planning stages—the City Gazette had remembered that back in 1739, the colony had been assisted by “a negro man belonging to Mr. Spry, who lately took one of the slaves that was concerned in the Insurrection at Stono . . . ”

This is an aspect rarely brought up, regarding the Stono Rebellion—that more than a few black slaves acted to protect their owners, hiding them until the violence was past. Others tried to talk the rising slaves out of their plan. In some cases, an enslaved person even confronted the rebels. These slaves were said to have “bravely withstood that barbarous Attempt,” even at “the Hazard of their own Lives.” A man called July, belonging to one Thomas Elliot, was “very early and chiefly instrumental in saving his Master and his Family from being destroyed by the rebellious Negroes [and] at several Times bravely fought against the rebels, and killed one of them.” July received the ultimate gift, his freedom, “for an Encouragement to other Slaves to follow his Example in Cases of the like Nature.” Other slaves were given lesser rewards (clothing, mainly, and perhaps a little money) for having “been of great Service in opposing the rebellious Negroes.”

There may be a temptation to read the decisions of these individual slaves (the ones who remained “faithful” to the whites) as a form of race-treason, or as cowardice. That interpretation cannot be dismissed. Doubtless some of the other slaves saw it that way. But we must remember and give equal weight to the shock and violence of the situation. The cause of the rebels was profoundly just—it was the great American cause, Liberty—but on that day, September the 9th, they were in the midst of committing mass murder. If the person in danger were someone who had treated you well, your mistress, or a child, possibly your child, who is to say how a morally coherent person would or ought to have behaved at a given moment? Also, the material rewards offered—other than freedom, that is—the clothes and shoes and spending money, may seem paltry to us, especially for literally life-saving service, but the enslaved would have seen them very differently. There was desperate necessity to consider.

Ambiguous. Messy. And yet very clear. The rebels wanted freedom. They were given death.

When the Stono Rebellion is mentioned today it is most often, unexpectedly, in the context of American musical history. Recall that business of the drums—after the fugitives had “halted” in the field, they started “beating drums to draw more Negroes to them.” They were not drumming randomly or playing in the belief that the mere noise of the drums would bring more slaves running. They were broadcasting code. Familiarity with the technique of what more than a century later came to be called “telegraphic drumming” was (and is) common in multiple regions of Africa. Drummers belonging to various cultures there have long been able to send fairly complex messages over vast distances by employing different percussive rhythms. An essay in the December 1928 issue of Opportunity magazine (a “Journal of Negro Life” that grew out of the Harlem Renaissance and became one of the most influential African-American publications of the first half of the twentieth century) discussed this phenomenon. “Africa has had for centuries a radio system of its own,” wrote the author, Nana Amoah III, an African statesman who had traveled to the United States and visited black communities (and who was, at home in present-day Ghana, the chief of the Fante tribe). “A simple system of course,” he continued, “but quite efficient—The Drum.” He explained that in parts of Africa, a man “sits astride” a particular kind of drum and “beats it with two sticks or a stick and the palm of his hand to produce sounds like the Morse Code. State drummers like telegraph clerks are trained. The position is hereditary and every member [who] belongs to a particular family in a state is trained.”

The colonial authorities in South Carolina had realized that something like this was going on, in connection with the insurrection of 1739. And Stono was not the first occasion on which music and dancing had gone hand-in-hand with insurrection in the white colonial mind. Nearly a decade earlier, in 1730 (this according to a 1756 article in the London Magazine), a large group of slaves had gathered “at a certain place in the neighbourhood of Charles-Town, under pretence of a solemn dancing-bout, from whence they were to rush all at once into the town.” After invading the city they would “massacre all the white men in the town and . . . spread the destruction thro’ all the plantations in the country.” The code required that “all due care be taken to restrain . . . the using or keeping of drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes . . . ”

It is not clear to what extent this rule was enforced, or enforceable. Perhaps most slave owners in the eighteenth century would have agreed with a later, nineteenth-century South Carolina judge, the Hon. J. B. O’Neall, who in the early 1850s (in an essay inserted into J. D. B. De Bow’s Industrial Resources, Etc., of the Southern and Western States) referred to the drum ban as “one under which most masters will be liable, whether they will or not. Who can keep his slaves from blowing horns or using other loud instruments?” O’Neall declared that “the sooner it is expunged from the statute book the better,” but that section of the act remained technically in effect until the end of the Civil War. There must have been a span of time, however, if only in the period immediately following the Stono Rebellion, when drums were prohibited and taken away from the slaves. There was a generation, perhaps, that grew up without them, and then the strength of that old drum tradition was weakened.

It is this incident, of cultural disruption, that—in the view of some scholars—may have exerted influence on the evolution of African-American music and dance. The theory is that, in the sudden absence of the instruments that had typically provided percussion, the slaves incorporated the percussive element more fully into their dancing and strumming. Their dance came to involve more “patting juba” (slapping of the body with the hands, and rhythmic stomping of the feet), while their manner of playing the banjo and fiddle became more syncopated, with a more aggressive attack. A century later you had tap dancing and the African-American string-band style. This is simplistically put. For that matter, the argument itself is a bit simplistic. Needless to say, there can be no surviving evidence for this causative linkage. Still, there is something about the idea. It is compelling if not convincing.

The Stono drum thesis was first put forward by a scholar named Marian Hannah Winter, a mid-twentieth-century historian of dance who published most of her work in a magazine called Dance Index (edited by Lincoln Edward Kirstein, a co-founder of the New York City Ballet). Winter was a New Yorker and an interesting person. In 1939, right before she was invited to start contributing to Dance Index, an item in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described her this way: “Marian Hannah Winter, heard on WNYC in the series, ‘Music of the Orient and Primitive Peoples,’ is on the staff of Brooklyn Museum. She is a graduate of Radcliffe. Recently she took the policewoman’s exams and came out on top. She is fond of mink coats and blue Picassos, of which she has neither.”

In 1947, Winter published an article, titled “Juba and American Minstrelsy,” considered an important early study of the topic. She was a writer of her time, prone to statements such as that the Slave Code of 1740 “would have discouraged any people inherently less musical” than African Americans, but her overall theme—that many of the traditions of minstrelsy were authentic artifacts of black plantation culture, as opposed to white caricatures and bastardizations—was progressive, both politically and in the sense of being ahead of its time. Her essay includes this crucial paragraph:

Substitutions for the forbidden drum were accomplished with facility—bone clappers in the manner of castanets, jawbones, scrap iron such as blacksmith’s rasps, handclapping and footbeats. Virtuosity of foot-work, with heel beats and toe beats, became a simulacrum of the drum. In modern tap-dancing the ‘conversation’ tapped out by two performers is a survival of African telegraphy by drums.

This theory has since passed into the broader literature on the history of tap dancing. Dozens of writers have repeated versions of it, usually without mentioning Winter’s work. The choreographer Mark Knowles, who does cite her, offers a succinct paraphrase of her thesis in his defining 2002 study Tap Roots: the Early History of Tap Dancing: “Denied their most prevalent, and indeed sacred means of expression, the slaves substituted the forbidden drums with bone clappers, tambourines, and most importantly, hand and body slaps, and foot beats. The most primitive of all instruments, the human body, became the main source of rhythm and communication.”

Only a time machine would allow us to prove or disprove this conjecture. And yet somehow, no examination of the musical history of South Carolina, and in particular of the African-American musical traditions there, would be complete without it. If its claims regarding the development of tap dancing must remain forever in a zone of maybe-maybe-not, it demonstrates something else with great certainty, namely that the cultural memory of the Stono Rebellion remains an active if obscure element in our perpetual reformulation of the deep Southern and American pasts. Just as Cato of Stono spoke to and through his descendant, George Cato of Columbia, the banning of drums in 1740 speaks to the histories of tap and the minstrel banjo. It contains a truth deeper than the musicological possibility, one having to do with slavery itself and African-American cultural heritage. So much was taken away from those people, and much denied them, almost everything. Their response was creative and transforming. They were not surrendered.

1 There is a theory, first put forward by Peter Wood in Black Majority, that “cowboy” is a Carolina word. On the plantations, “the care of their livestock often fell to a black. The slave would build a small ‘cowpen’ in some remote region, attend the calves, and guard the grazing stock at night.” Wood asks, “Might not the continued predominance of ‘cowboy’ over alternative terms such as ‘cattleman’ represent a strange holdover reflective of early and persistent black involvement in the American cattle trade?”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.