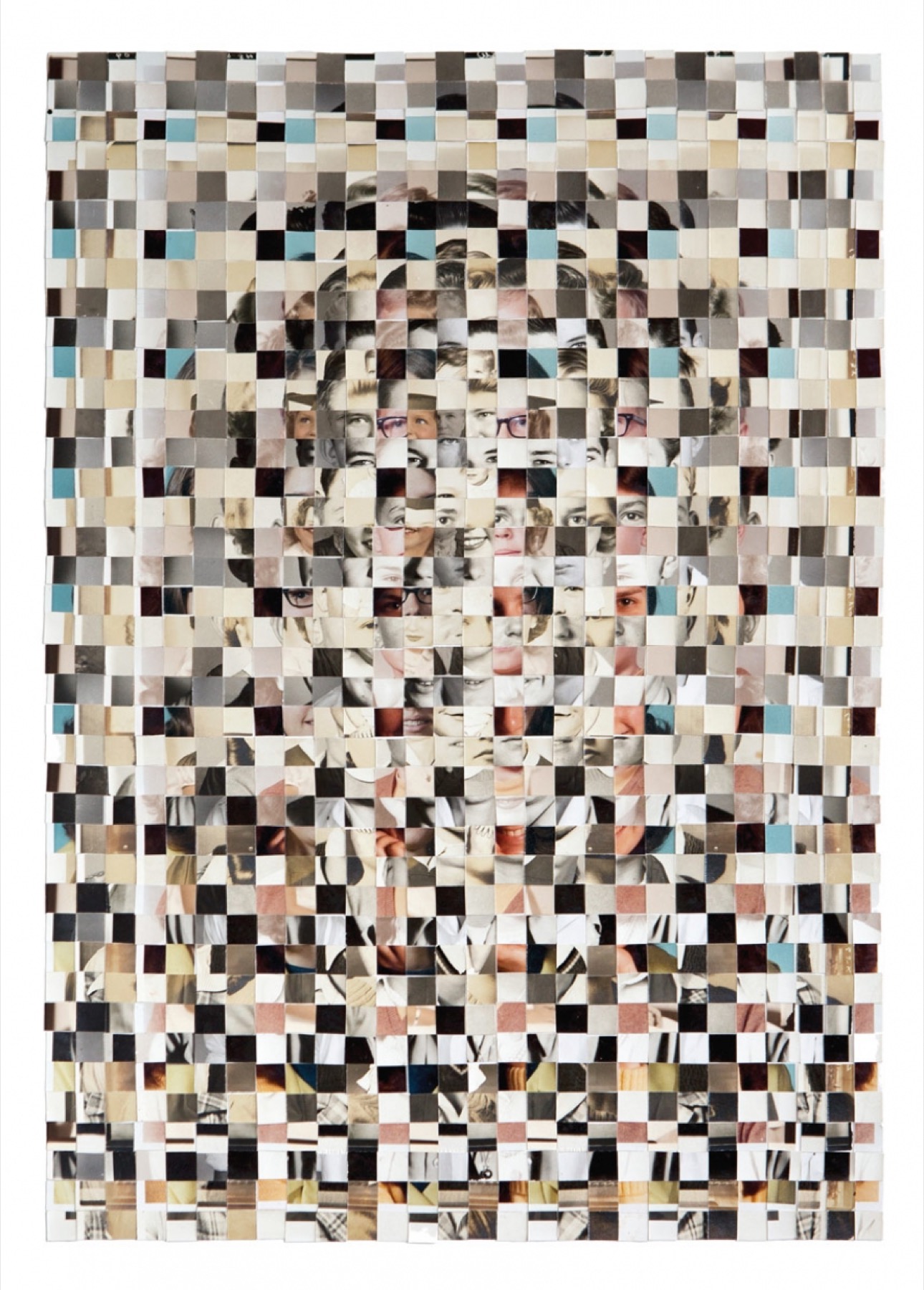

“Studio Portrait” (2017), by Joe Rudko. Found photographs on paper, 30 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle

The Messy Middle

By Eliza Borné

A Letter from the Editor

In 2015, journalist Emily Gogolak flew into San Antonio, rented a car, and checked into a motel near Dilley, home of the South Texas Family Residential Center, a place today associated with the dismantling of this country’s asylum system. Gogolak attended asylum hearings that became seared into her memory—for the detainees’ raw emotion and for the guards’ seeming indifference. “The center itself is so startlingly strange that it feels fake,” she told me, “and the pain and trauma inside are overwhelming.” As she got to know the town, she fixated on the idea that studying Dilley is like gazing through a window into a particular experience in rural America. “It’s a place selected by the prison company, I came to realize, not only for its poverty but also for its veneer of placelessness,” she said. “It’s a town where so much capital is passing through—corrections, oil, narco-trafficking—but little remains.”

After moving to Texas in 2017, Gogolak returned to Dilley—first only in passing, stopping off I-35 from Laredo, where she was often reporting, to have a coffee, eavesdrop, chat with oil field workers over a Modelo. With time, she came to appreciate the people who live in the town, and she’d linger for days at a time. How did the South Texas Family Residential Center come to Dilley, she wondered, a town previously known for its watermelons, and why? Gogolak started to piece together a social geography rendered in fragments, what she now describes as her “cubist narrative.” In her epic essay, “An Intersection at the End of America,” we meet Dilley residents who have been affected by seismic shifts in their town’s economy and culture: the bartender who grew up laboring in Dilley’s once bountiful melon fields; the oil industry worker who aspired to join Border Patrol or ICE but became disillusioned after losing her job in the detention center; the activist filmmaker and elected official increasingly frustrated by what he views as dysfunction in Dilley’s governance. Though Gogolak’s portrait is unique to Dilley, her inquiry resonates with large swaths of the South. What does it take to improve the fortunes of a small, struggling town in the twenty-first century?

Gogolak’s essay is paired with haunting photographs by Gabriella Demczuk, who captures the bleakness—and stark beauty—of this region. “There’s something about driving south on I-35, the traffic in San Antonio falling farther and farther behind, when the sun is setting and the brush takes on a bluish hue and the sky is prettier than a Turner painting,” Gogolak said, “and you get why people from there don’t leave.”

As this issue was going to press, I marked seven years of working at the Oxford American. In that time, writers and readers have occasionally asked me to describe a “typical” OA story. There’s no such thing, as this issue demonstrates—here, you’ll find a fascinating opus on Afro-Cuban religions in Miami (Jordan Blumetti’s “On Sacred Ground”) alongside a taut short story about a woman existing in a bewildering in-between place after the death of her mother (Ben Fountain’s “Cane Creek”). You’ll find wrenching yet tender love poems, intense fiction, intimate memoir, and deft reportage years in the making. I love this variety, as impossible to characterize definitively as our perplexing region.

Still, over the years, I have come to admire a certain kind of story that the Oxford American, as a quarterly magazine untethered from the demands of a rapid news cycle, is especially well suited to publish. With love, I call it the “OA special,” though “passion project” works just as well: stories that writers have been chasing for years, often to the point of obsession, hooked by a question or a place or a character. Gogolak’s Dilley story is a perfect example. Another is “You Never Can Tell About a River,” KaToya Ellis Fleming’s essay about family, the author Frank Yerby, and their shared hometown of Augusta, Georgia. Rarely remembered today, Yerby, who died in 1991, was an African-American novelist famous in his era for writing a best-selling antebellum romance novel that was made into an Oscar-nominated film. Yerby’s story is complex. His books, some of which include racist stereotypes, were explicitly marketed to an enthusiastic white audience, who generally did not know he was black. Black audiences who were aware of Yerby’s true identity were critical of his choice of subject matter. In grad school, determined to follow up on a beloved uncle’s suggestion that she write a book about the enigmatic author, Fleming set out to write a biography. Before long, the project turned much more personal and launched Fleming on a quest that brought her to the offices of the Oxford American, where she has been apprenticing since September as our 2019–20 Jeff Baskin Writers Fellow. Her fellowship includes time to work on a nonfiction book manuscript. Fleming has been researching and writing what she now calls a “bibliomemoir,” and her essay is an excerpt from the work in progress.

A line from Fleming’s essay has stuck with me: “Sometimes when you lose someone, someone you’re not sure you can live without, you do what you can to keep them present in your world. To make them feel real again.” Who among us can’t relate to this need—to honor our departed loved ones, to make them feel real? In Louisiana, family members descended from victims of the Thibodaux Massacre of 1887, when black sugarcane workers were murdered and left in a mass grave, are making efforts to do just that as they work toward digging up the gravesite and giving their ancestors a dignified burial. In “Persons Unknown,” Rosemary Westwood interviews these descendants, who were photographed by Nina Robinson in Thibodaux. This is a story with no easy resolution, but the messy middle feels instructive, especially in our age of disagreement over how to memorialize the past.

Come to think of it, maybe this is what links many of our strongest Oxford American stories: they face history, reckon with the middle, and then ask the hard questions about what comes next.

View the Issue 108 Table of Contents.

Order the Spring 2020 issue today or subscribe to the Oxford American.