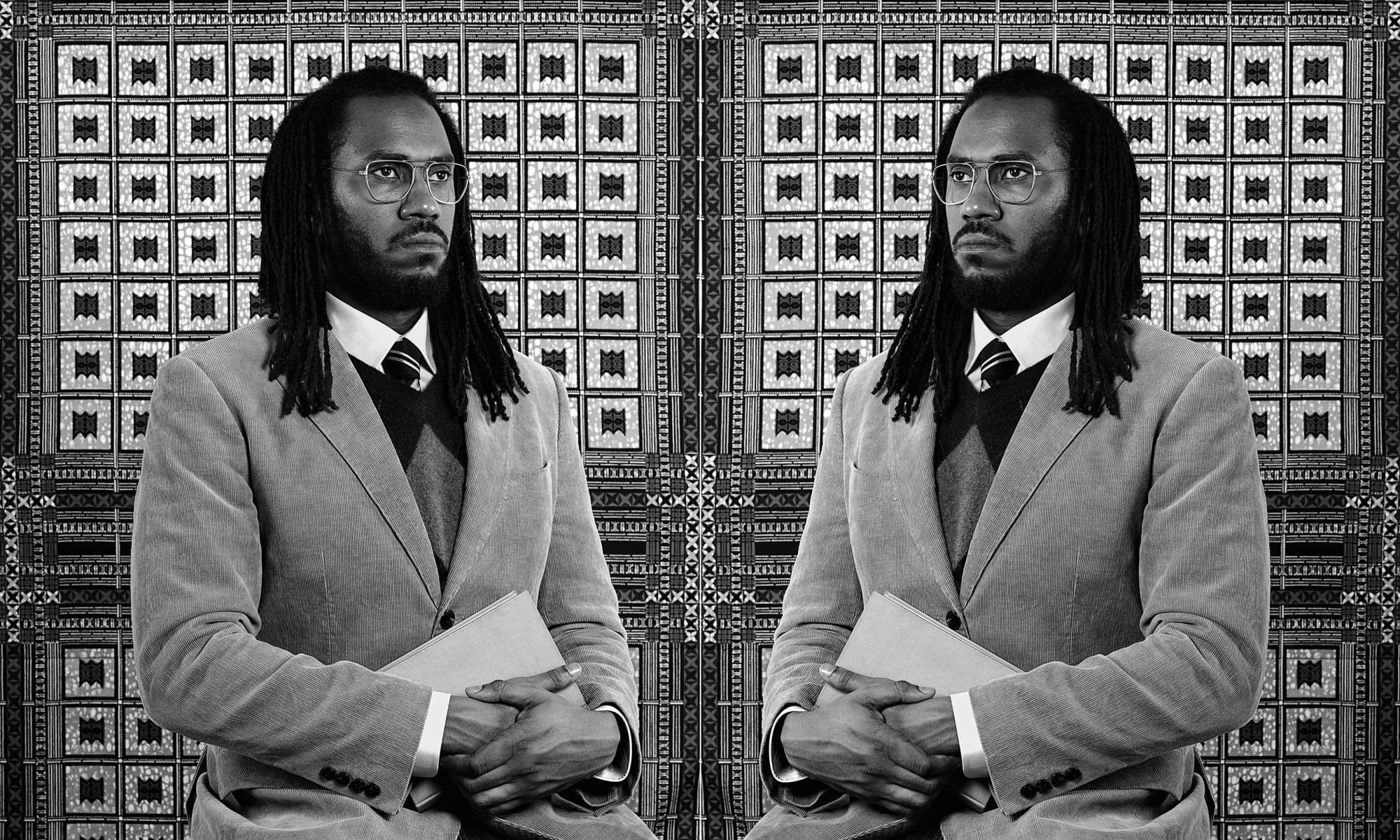

Self Portrait as the Professor of Astronomy, Miscegenation and Critical Theory at the New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club Center for Graduate Studies, 2008 © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist

Welcome to Y’all Street: Inside the Summer 2025 Issue

Associate Editor Frederick McKindra on the tension between business and the humanities

By Frederick McKindra

This introduction appears in the Summer 2025 print edition with the title “Conflicts in the Market.” Order the Y’all Street Issue here.

I never stepped foot inside the School of Business at my university. Still, it had an outsized impact on my collegiate experience. Even by 2002, the year I entered college, I thought of it as the most popular professional endeavor on campus. Sure, the STEM fields were ascendant then as well, as was the School of Communications, but nothing topped the imposing face of the building belonging to the School of B, perched atop a campus that unfurled beneath it down the hill.

My antagonism toward business and industry began there, I think. Before arriving at Howard, I’d barely learned what an “internship” entailed—my meager plans for the summer after freshman year included returning home to work full time as a camp counselor at a church program for elementary school students. But here, my classmates from the business school were already vying for competitive summer internships.

Their Business Orientation class instituted an air of professionalism that set them apart. It seemed they’d already been fashioned by a process that would guarantee each of them a measure of success. I can’t say whether that actually resulted in institutional favoritism, but it certainly felt that way.

Each Tuesday and Thursday, freshman students in the School of B were required to come to class in business professional dress, a flood of men and women in black or navy suits trooping across the yard from breakfast at “the Caf” into the waiting mouth of their building. The suited students wafted over the entire yard, a kind of airborne pollutant to the De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest-ian tinged dream of black bohemia I’d smuggled onto the campus with me. It felt like they were muting the legacy of color and vibrancy Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway and Phylicia Rashad had left on the campus. I looked at my classmates in disbelief, disheartened that they were not interested in making a world with me. Instead they seemed ready to acquiesce to one that guaranteed them financial security at the cost of self-determination.

Their lives appeared absent of uncertainty, and there was something enviable about that, for an eighteen-year-old aspiring writer with little direction on how to create a career out of my ambitions beyond the author biographies I found and read in the library.

My underlying existential terror took years to diagnose. It was angst over the superficial that raised my ire then. But speaking with a friend the other night, I was reminded of how pretentious and demeaning the gesture felt. He recalled that the suit dress code, on black bodies, at a place like Howard, was a pervasive imposition that seemed to say, “We need to show massa that we the best.”

This visible indoctrination undermined the radical vision I’d imagined of Howard. We couldn’t be self-determining, because in truth, none of us had the money to be. If W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington had argued a century earlier about the merits of a liberal arts education versus an industrial one, how would they have landed on this debate now between the humanities and the corporation?

I turned my back on business and industry then, hoping that if I resolutely denied its power over my life, I could successfully make my way as an anticapitalist. After college, I moved to Bushwick, Brooklyn, then on to Williamsburg, naively believing that if I followed the creative herd, I’d find a way of sustaining myself. My anticapitalist stance never incited much action beyond my writing desk though, as I sat out the Occupy Wall Street protests between my apartment in Brooklyn and classes for my MFA at the New School. Still, I nursed a resentment toward those with starting salaries that actually made the city livable. I also resented the prestige of the institutions they were aligning themselves with. I closed myself tightly against the omnipresence of money as its own end and subconsciously fashioned myself into a Luddite in terms of making any of it.

Though I still struggle to identify the distinction between buy-side and sell-side, the corporate world retains some of that early enviable glamour to me. Media has managed to metabolize it in a way that tugs at my curiosity. Succession, Severance, and Industry have all given me a peek inside the corporate aesthetic I’ve had so little access to. The almost two decades of personal optimization my corporate peers have accumulated since we entered the adult world appears quite sexy from the vantage point of a frumpy, debt-saddled English major still half-reliant on the spark of inspiration to make any new product to take to the marketplace in hopes of making ends meet. There’s something about watching someone in a well-tailored suit enter a room to buffets of sumptuous food and free-flowing drink that draws me to look beyond the boundaries of my worlds of literature and non-profits.

There’s a titillation I get from watching creators like Corporate Erin spoof company managers, or reading articles on the promulgation of fleece vests as the uniform of finance bros. It’s like I’m finally giving myself permission to look at those classmates of mine from Howard, to interrogate the decisions they were making then, and sometimes to ask myself “would I have chosen differently, knowing what I know now?”

For me, this Y’all Street issue was a chance to indulge in examining this tension that has existed in me for more than two decades. What would happen if we applied the techniques and lenses we usually train on music, or literature, or architecture in the South to industry in the region? What might we uncover that gets overlooked in national conversations about the South, a region historically seen as blighted by its history of agriculture and extractive industry and forced labor?

The term Y’all Street was coined to describe Dallas’s burgeoning financial hub. In this issue, we’re borrowing the colloquial sobriquet to highlight the thriving, declining, and emerging economies throughout the South.

Chris Pomorski talks with contract farmers across the region working to nullify relationships with corporate poultry producers, proof that there’s still hope to be found when family farms escape the clutches of Big Ag. Michelle Orange scopes out greyhound racing in its waning days, weighing both sides of a years-long battle to outlaw the sport in West Virginia. And Katie Jane Fernelius reports from Louisiana, where Dollar General workers have been organizing to demand changes including improvements in workplace health and safety conditions.

The stories herein interrogate the complexity of business interests in the South, a place that doesn’t always move the profit needle. Fulfilling the appetites, dreams, and ambitions of a region and a people sometimes grown stubborn, insular, or just plain poor by the place’s physical landscape, its rurality, calls forth some innovative ideas—Leah Garcés’s Transfarmation Project, the in-state politicking of Carey Theil and State Senator Ryan Weld, the local organizing of groups like Step Up—and at times some exploitative ones.

Hopefully, this issue ignites a dialogue between what have long felt to me to be two diametrically opposed worlds—the literary and the corporate. I won’t say that some of my best friends are finance bros, but some of them do have tendencies.

Support the Oxford American

The Whiting Foundation will double your donation—up to $20,000.

Your donation helps us publish more work like the article you're reading right now. And for a limited time, every gift will be matched up to $20,000 by the Whiting Foundation.

Prefer a subscription? You'll receive our award-winning print magazine—though subscriptions aren’t eligible for the match.