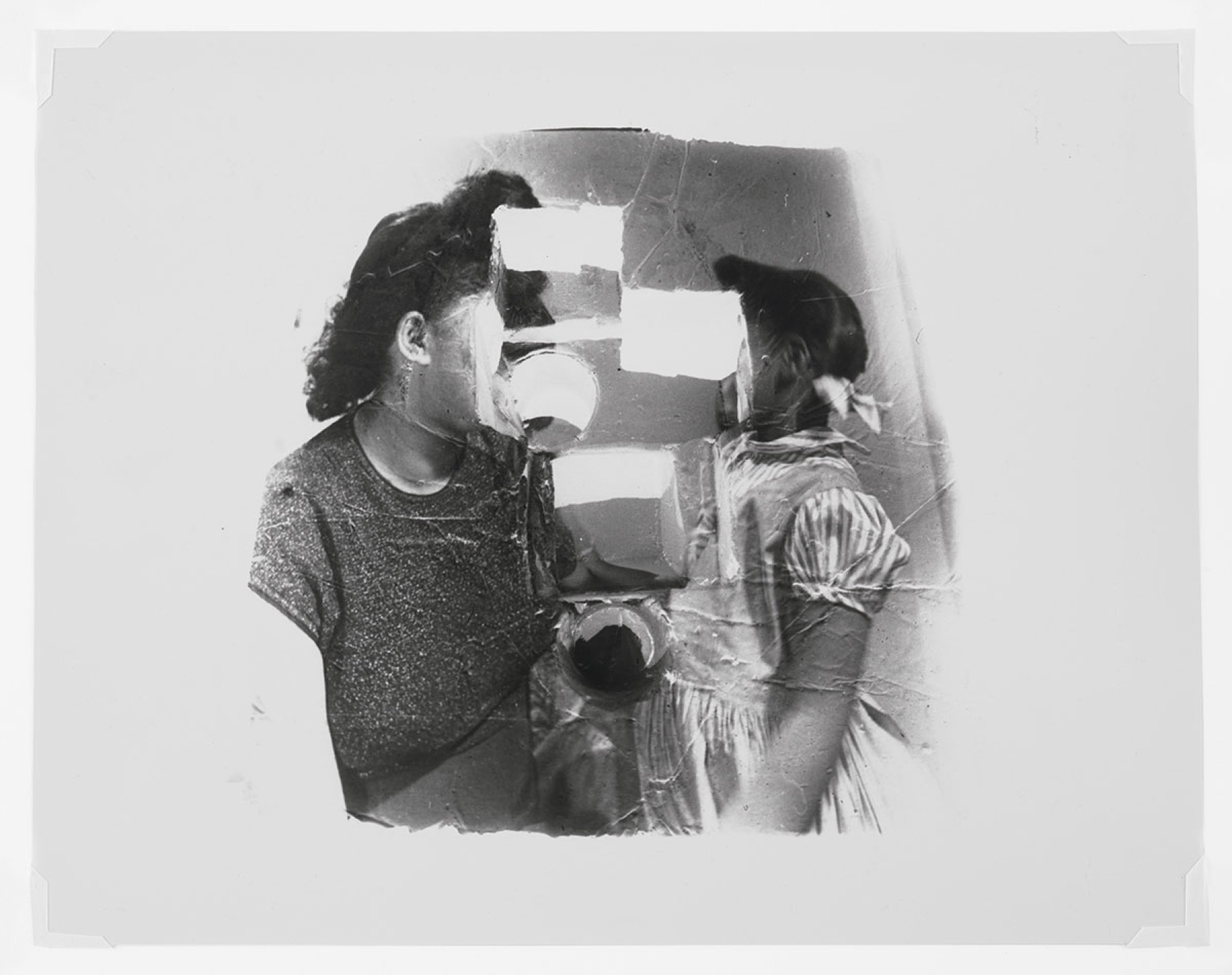

"Untitled (Mother and Laure)," 1990. Gelatin silver print by Darrel Ellis. Courtesy Candice Madey, New York and Visual AIDS. A comprehensive monograph of Darrel Ellis's work was recently published by Visual AIDS, and is available for purchase at visualaids.org.

Editor's Letter: We Are Ever New

By Danielle Amir Jackson

In early June 1992, then governor of Arkansas William Jefferson Clinton appeared on The Arsenio Hall Show wearing dark shades, a suit with a floral-print tie, and a tenor sax. He played Elvis’s version of “Heartbreak Hotel” at the start of the episode, and sat in with Hall’s band, the Posse, through Hall’s entire opening monologue. Before the commercial break, they played “God Bless the Child,” written and made famous by Billie Holiday, and after, the two sat down to discuss Clinton’s candidacy for president. He’d visited Arsenio’s church, he said, getting to know “South Central L.A., before the riots.” Later on, Hillary joined them on the couch in head-to-toe yellow and commended the way Arsenio used his show as a community forum after the uprisings.

I remember from those days the frisson, the exciting electric current in anticipation of our region’s rise to a national stage for the first time in a generation. There was a sense that what was on the news was close enough to touch. Dear Dear, my step-grandmother Roberta Jackson, had been a city councilwoman in West Memphis for two decades and campaigned heavily for Clinton, who she’d come to know. There were rumblings his running mate would be our senator, Al Gore Jr. There were rumblings of film adaptations of John Grisham’s first two novels, which took place in a fictional Delta town and in Memphis, and were so infused with the smells of those places the movies couldn’t possibly be shot anywhere else.

That spring, on March 14, 1992, the first issue of the Oxford American appeared on newsstands. Founding editor Marc Smirnoff had found his way to Oxford, Mississippi, after a cross-country trip from his home state, California; a stint as a bookseller at Square Books; and a few years fundraising and gathering submissions. More than anything, I understand the urge to document the end of the Eighties and the beginning of the Nineties with a chronicle of some sort, a magazine—especially if you were driving through the South and got stranded some where like Oxford, somewhere near Memphis. I was a girl then, at Idlewild Elementary in midtown, learning new countries in eastern Europe, the lyrics to “La Marseillaise,” and all about Josephine Baker. My teachers and vital local arts institutions like the Memphis Public Library, Burke’s Book Store, and Playhouse on the Square raised me just as much as my mother’s cooking did.

Part of what was so exciting about the time was the feeling that every promise seemed possible; the violence and embarrassments of our past seemed like they might still be resolved, redeemed. Dr. King had been murdered here, and we were still struggling to integrate our classrooms. Even so, in the early Nineties, we opened the National Civil Rights Museum. Its high-tech segregated bus exhibit and the somber glass partition allowing us to peer into room 306 showed us a possible way forward, a way of reconciling and living with our past in peace. Before the assassination and the uprisings that followed, the Lorraine had been a notable Green Book–listed hotel, the only all air-conditioned accommodation in Memphis according to the 1960 edition. South Main had been a busy hub for shopping and entertainment. If we’d listened closely, though, we’d have heard what Ms. Jacqueline was telling us in her protest outside the new museum: We weren’t solving all of our problems by building a monument, and honoring the past requires remembering, but also ongoing work and effort.

The year the first OA issue published, my family was still mourning the passing of my dear uncle Pluto, who was really my first cousin, Frank Lloyd Edwards. He was my grandmother’s oldest grandchild; I am her youngest. He lived in her house as a boy and kept my mother, two years younger, his tiny aunt, company. His funeral program says he sang in the Glee Club and was part of the Student Council, the Red Cross, the Spanish Club and the Book Club. I remember him most vividly standing tall and elegant in the blue robe our choir wore on special Sundays. As an adult, he made a life caring about beauty and detail, as a hairdresser, fashion stylist, and occasional interior designer in Chicago and the San Francisco Bay. He had a loud laugh, marcelled his hair in the Sixties, and in the Eighties, wore it in a fade that was always precisely lined. My sister tells me he was the first person to call her “a beautiful Black woman.”

“Few survived the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s,” André Leon Talley wrote in the Chiffon Trenches, his second memoir. Talley endured the loss of numerous comrades, but kept his health long enough to break ground as a fashion editor and creative director at WWD, Ebony, Vogue, and Vanity Fair, championing Black designers and putting forth a vision of style as capacious and all-encompassing of humanity’s multitudes. Born in Washington, D.C. and raised by his grandmother in Durham, North Carolina, Talley never let us forget his “sense of style was anchored in the women I observed in the church.” The white gloves, carefully ironed patterned skirts, the hats sitting just so. These adornments have always been about more than what they seem. They tell stories of beauty as dignity, and armor, and triumph through daily adversity and toil and strife. We honor Talley, who passed away this January at seventy-three, an elder of our industry, an embodiment of our region’s elegance, grace, and hard work. Talley’s words do not appear in our archive. By honoring him, we acknowledge the silences there, and commit to giving them light and a hearing in the days and years to come.

The first issue of the OA, featuring Barry Hannah, Roy Blount, Jr., John Grisham, and Charles Bukowski, opened with a letter from Smirnoff saying he’d never publish a recipe or a story about a garden. It would be a serious magazine for a serious region, and the society ladies could do what they do. Of course, these days, we do publish the occasional recipe. And we care about every culture maker in the South, including Alice Walker’s garden-tenders and the ladies who lunch. Still, the writers and editors of the very first issue put forth a type of journalism that was as much about feelings and the sights and sounds of a particular place—about telling stories that teemed with life—as it was about the ins and outs of what happened. And through the past thirty years, what has remained steadfast, I think, is a commitment to telling tales like these, and giving them room to meander, and reckon, and trouble, and sing.

For our thirtieth anniversary, we won’t make a monument to our past. But we will spend the year honoring the storytelling tradition we have come to exemplify—by leaning into the work. We’ll publish a mix of old and new contributors and reframe and revisit writing and visual art from our archive with new framing and reimagined points of view.

In this issue, writers consider the many ways memories are made, forgotten, honored, and mined. New Orleans–born Jeanie Riess reckons with her father’s accident, which affected the literal way his cognition worked. Kelundra Smith remembers her years of schooling in the Eighties and Nineties through the lens of suburban Atlanta’s long-term battles over integration. Medieval scholar Katherine Churchill warns us how a fascination for the past can become corrupted; Rebecca Bengal highlights Winfred Rembert, who made colorful, panoramic works of art out of leather and memories of his near-lynching in rural Georgia. Imani Perry traces the history of “an African name in an American place,” by way of a contemporary song; a character in Kristen Arnett’s “Pigskin” remembers a loved one by getting a haircut.

With Verónica Dávila Ellis, we travel to Chicago, New York City, Puerto Rico, and points farther south to follow the musical trail of Ivy Queen, who Rolling Stone calls the First Lady of reggaetón.

We’re also proud to feature an extended lyrical sequence by Nashville poets Didi and Major Jackson, in which the latter writes:

The future is a blind piano man

fingering some groove out

of ancient beats from the Roman Empire.

And I read the piano man as all of us; we’re all falling forward, in darkness and uncertainty, trying to make music out of our detritus, and of our dreams and will and might. We are ever new... as the lyrics go to one of my favorite songs, by the Canadian electronic artist Beverly Glenn-Copeland. He’s alluding to Isaiah 43:19: Behold, I will do a new thing; now it shall spring forth. This year, the OA will create living, breathing artifacts that remind us of where we’ve been. They’ll also move, challenge, revise, dream, and reach out, toward new and better ways.