Really Gone

By Michael A. Gonzales

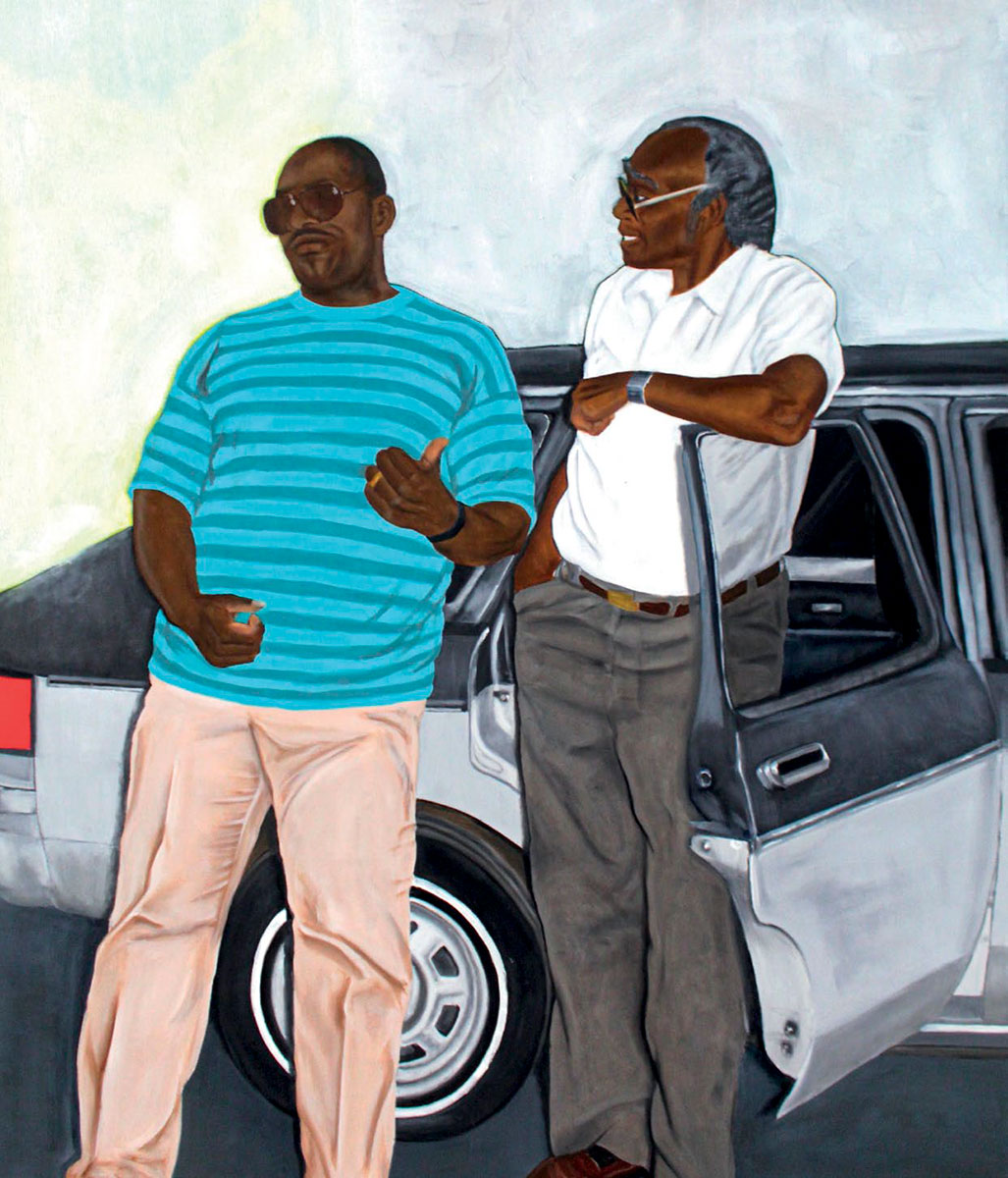

"I Bet He Didn't Know," 2021, oil on canvas by Michon Sanders. Courtesy the artist

Dusk was approaching when Malcolm Harris decided to treat himself to dinner and a movie. Slipping on his favorite brown tweed jacket, the one that made him look like a Brown University semiotics professor, he glanced in the mirror and brushed lint from his shaggy beard and short Afro. A widower since 2000, for the last two years, he’d almost grown used to not hearing his late wife Lenore comment on his wardrobe choices. Walking over to 7th Avenue, he subwayed down to Varick Street and ambled through the wooden doors of Brother’s Bar-B-Cue. After a juicy meal of chicken and ribs, he crossed the street and went to the seven o’clock show of Robert Mitchum’s noir thriller The Night of the Hunter at Film Forum.

It was the last night of its five-day run, and the theater was filled with movie buffs, many of them alone. Malcolm had seen the movie before, but he never tired of viewing it on the big screen. Ninety minutes later, he exited the theater refreshed and inspired. He wanted to make it back home by eleven to finish writing his essay on Black rock musicians for Bliss, the music magazine where he was a senior writer. Though it was chilly, he decided to walk home and mull over ideas for the article.

Approaching 16th Street, scaffolding extended down the entire block. Usually, he would’ve detoured onto the street instead of walking beneath the dimly lit plywood tunnel, but he was so lost in thought he didn’t notice much until a skanky, skinny Latino man stepped out of the shadows. The guy wore dirty sneakers, too-big jeans, and a busted Members Only jacket that was new twenty years ago. “Give me your money,” he shouted in an accent that sounded Dominican, taking Malcolm by surprise. Dude was obviously a junkie. There was a gun in his shaky right hand.

“You’ve got to be joking,” Malcolm muttered and chuckled. Perhaps it was nervousness that made him laugh, but, whatever the reason, the Skeletor-looking fool fired three times and ran away. Collapsing to the ground, Malcolm thought, “The bastard didn’t even take my damn wallet.” A woman coming out of the bodega screamed at the sight of Malcolm bloody on the ground while her companion called 911.

With sirens howling, the ambulance arrived quickly. The bearded EMS guy who helped him wore a nameplate that read Elvis Conzo. The ride to St. Vincent’s Hospital took three minutes, but Elvis assured him, “There weren’t any vital organs hit that I can tell. Just don’t close your eyes, because I don’t want you to pass out.” Malcolm was in less pain than he thought he should be.

“Thank you,” he whispered as the workers wheeled him from the ambulance to the emergency room, where doctors and nurses were waiting for him. As the staff worked on Malcolm, cutting open his chest to insert a breathing tube, he conjured Jimi Hendrix’s mellow blues solos in his mind. Hours later, Malcolm was wheeled on a gurney to the basement for X-rays and then taken to the ICU, where for the next ten days he was a patient.

At dawn, before the urban magazine publishing world found out he’d survived a bullet to the chest, one to the thigh, and another in his side, Malcolm lay silently and watched the sun rise over the rooftops of downtown Manhattan. Hours later, the phone rang. “Malcolm?” He was shocked to hear a soothing voice he hadn’t heard in many years. It was his stepmother Evelyn, whom he hadn’t spoken to since she and his father Linwood moved from their suburban castle in Westchester to Bennettsville, South Carolina.

Although he and Linwood had a sometimey relationship, talking only periodically, Malcolm always loved and respected his stepmom. A former nurse, she’d been married to Linwood since Malcolm was a toddler. Still, her call threw him off. “Your mother phoned earlier and left this number on the answering machine,” Evelyn said. “I’m so sorry to hear what happened to you. Are you in a lot of pain?”

“I was, but it’s not as bad right now. This morphine drip is doing its thing.” With the exception of having his tonsils removed when he was six, Malcolm had never spent the night in a hospital. “I’m OK.”

“Well, thank God.”

“Is everything cool on your end?” Obviously, something was wrong.

“Well, not really. It’s your father. He’s in the hospital as well.”

“What happened?”

“He was fine until two days ago. Then, he called me into the bathroom. He had just urinated blood.”

“Oh, God, what does that mean?”

“They don’t know yet. The doctors are running tests.”

“Is he conscious?”

“He’s conscious and sitting up in bed talking to people.”

“Trying to sell them Amway,” Malcolm said, laughing.

“You remember those Amway days, huh?”

“How could I forget? I think Linwood’s still mad he didn’t achieve Diamond status and become a millionaire. Remember, I went to that convention with him in North Carolina back in 1982. That was my first and only time down South with him. We spent Easter at his mother’s house in South Carolina first. That was the last time I was down that way.”

“Yeah, I was just asking Linwood a few weeks ago why you have never come to visit since we moved down here. You travel all over the world to do interviews, but you can’t come to South Carolina to see your family?”

Feeling guilty, he stammered, “I’ll try to come down there next year, I promise.” They both knew he was just talking to be talking, but it was cool. Malcolm just didn’t want Evelyn to ever think that he had anything against her. Though he never mentioned it, he remembered well how, when he was a kid, she used to take him to the movies and then to Baskin-Robbins for peanut-butter-and-chocolate ice cream.

“It’s so strange, both of you being in the hospital at the same time,” she said. Evelyn gave him the phone number to Linwood’s hospital room. He promised to call the following day. Moments after he hung up, a smiling, straight-haired nurse came into his room. Wearing a white cap over short locks, she looked at his chart and took his temperature. Standing over him in her freshly washed and pressed white uniform, she smiled. In a light West Indian accent she said, “You must have angels flying over you.” Perhaps Lenore’s spirit was visiting him, making things smooth, sending him blessings.

When the nurse left, Malcolm turned on his side and watched as two pigeons soared through the air. The blue sky and white clouds were the perfect backdrop as the birds flew in circles before finally landing on his window ledge. He heard their cooing through the glass, watched their heads bopping. Malcolm relaxed and stared at the black-winged creatures until his lashes fluttered and he slowly slid into slumberland.

Two decades before, when Malcolm was twenty, he and Linwood had taken a road trip to his dad’s hometown. That was to be his first time meeting his grandmother and aunt. He sat waiting for Linwood outside his massive apartment building, chilling on the stoop with his suitcase. It was the same spot he’d, as a boy, waited over the years for his father to take him shopping or whisk him away for a weekend visit. Sometimes, without ever giving a reason, Linwood didn’t show up, and Malcolm would sit outside for hours waiting until his mother came and got him. “That man is just so trifling sometimes,” she said as Malcolm held back the tears. “Whatever you do in life, try not to be a trifling man.”

However, that Good Friday evening, Linwood was surprisingly on time when he pulled up. Though he usually drove a gray Volvo, he’d borrowed Evelyn’s shiny blue Cadillac for their road trip. Malcolm was pleased that his father had actually come through on a promise.

Rolling down the window, Linwood smiled. A handsome, portly man, he wore, as usual, a suit; Malcolm had heard for years that they resembled one another, though he preferred jeans to slacks and turtlenecks or t-shirts to collared shirts and ties. “The trunk is full of stuff, so put your bags in the back,” he said. Malcolm got in the front seat, buckled the seatbelt, and sighed with relief.

Their journey had started awkwardly. Both he and Linwood were tight-lipped with one another, neither really knowing what to say. It had been like that since Malcolm was a kid. Still, it was a ten-hour, six-hundred-mile drive to Bennettsville, the longest they’d been alone together.

“How’s school?” Linwood blurted.

“It’s OK. My grades are good. I have a girlfriend now.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah. We met at the school paper. Her name is Denise. She’s an editor.”

“Isn’t that a conflict of interest?”

“Nobody cares. I think I love her.”

"You wear condoms?"

Malcolm started laughing. “Yes. No need to worry about that. Denise makes sure.”

It was the first time he’d ever talked about sex with his father, though he’d heard countless stories from his mom about the man’s libido and cheating ways. It was the reason they had split up before Malcolm could walk. “He was screwing some older woman who lived upstairs from us in the Lenox Terrace,” his mother told him years before. “I trapped her in the mailbox alcove with the stroller that you were in.”

In Delaware they pulled into a gas station. Linwood handed him a twenty-dollar bill. “Just regular,” he said.

“Regular what?”

“Regular, regular. Haven’t you ever pumped gas before?”

“I don’t even know how to drive.”

“Yeah, well…pumping gas is easier.”

After paying for the gas, Malcolm unscrewed the fuel cap and spilled a little on the ground before he finally got the nozzle in the tank correctly. He felt a manly sense of accomplishment that surprised him. Climbing back into the car, he glanced out the window at the large trees on both sides of the road.

“I can’t believe you’re finally taking me to meet your family.”

“Yeah. I’m sorry. I know I’ve been saying for years I was going to take you. You know…”

“Yeah, I know…shit happens.”

“For someone who wants to be a writer, you talk kind of crudely. Try to curb your language around your grandmother.”

“I know how to talk around older Black folks,” Malcolm said. “Do I have to call her Grandma? Seems kind of weird calling a stranger ‘Grandma.’”

“Call her Mrs. Porter or Sister Minnie. That’s what the church people call her. She won’t mind if you don’t call her Grandma. I’m sure it’s weird for her too.”

On the radio there were fire-and-brimstone preachers on one station and old school country music on another. Reaching into the glove compartment, Linwood pulled out a cassette tape of an ancient B. B. King album. Malcolm’s mom had once told him about his dad’s love for the blues, but the old man had never revealed that side to him. “Oh my God, yes,” his mother said laughing the year before, “when I met your father he had just come North with a mouthful of gold teeth, a head full of conk, and B. B. King songs on the brain. He sang them songs in the mirror while playing an imaginary guitar.”

Two decades later Linwood had shed his country boy ways—everything except the accent—and was a city suit-wearing Black conservative who worked for the Housing Authority and integrated the suburbs. However, that night as they zoomed down the dark highway, Linwood turned back the hands of time as he drove toward Bennettsville playing that old B. B. King tape that opened with the weary “Three O’Clock Blues.” Malcolm picked up the case and saw the vintage picture of a young B. B. with a pompadour hairstyle, plaid jacket, matching bowtie, and mile-wide smile. King looked more like a man who gave the blues rather than got them. He imagined that Linwood had a similar look decades ago.

“What you know about this?” Linwood asked, slapping him on the leg.

“Not much. The only blues I know has an ‘R’ in front of it.”

“Captain, when I was your age B. B. King was my Michael Jackson. This here is Blues 101.” Linwood laughed before sliding his nottoo-bad singing voice into the last verse as though he’d sung it a million times. When the track finished, he turned the music down but let the tape play. “You know, my father died last year.”

“I had no idea. You never talk about your family to me. Except that time you told me you might have some old comic books in your parents’ attic. I’ve never even seen a picture of them.”

“My father was a truck driver. Eighteen-wheeler. He was up and down these roads all his life. He read a lot too, mostly history. He used to pick up those funnybooks for me when he was on the road. Cannonball Comics, Action, Detective. He even gave me a few Disneys. Thinking about it now, he might’ve even read ’em himself. You two would’ve connected instantly.” It took a lot for Malcolm not to say something sarcastic, to simply let his father have that moment of remembrance for his own dad.

In the middle of the night, he and Linwood damn near died on the highway in Virginia. Malcolm had dozed off and, when he was jolted awake (by Jesus, he was convinced), he realized his father was asleep and in the process of driving off the road. “Linwood!” he screamed, and his father’s eyes popped open and he got the car straightened out.

“Some co-pilot you are,” Linwood said laughing a few minutes later.

“What are you talking about? Didn’t I wake you up before you drove us off a cliff?”

“A real co-pilot wouldn’t have let me doze off in the first place.”

“It was your idea to make this a night trip instead of a day trip.”

Minutes later they were sitting by a window in a booth inside a diner called Wally’s. Inside were truckers biting into burgers, sopping egg yolks with toast, and talking to one another about their midnight journeys. Linwood ordered coffees for himself and Malcolm. The weary middle-aged waitress brought them over promptly. It wasn’t until after they ordered, and the waitress left, that Malcolm realized he didn’t have a spoon. He let the coffee sit for a few minutes.

“You’re going to let your coffee get cold?” Linwood asked.

“I’m waiting for a spoon.”

“A spoon?”

“Yeah, to stir the coffee.”

“Just use what you have; stir it with the butter knife.” Malcolm sighed but took the advice. As much as he hated doing it, at least he got to drink the coffee before it cooled down. Years later he’d swear that “just use what you have” was the best advice his daddy had ever given him.

“Let me tell you something before we get to the house.” He paused when the waitress returned with their pancakes and bacon.

“Yeah?”

Linwood poured syrup over his food. “If your grandmother and aunt start asking you a bunch of questions, don’t feel like you have to answer everything.”

“Why kind of questions?”

“Question questions. They’re nosy. You never know what they might ask.”

Hours later, Linwood pulled into the driveway as dawn shone through the windshield. In the house next door, a dog barked loudly. While Malcolm retrieved their luggage from the backseat, his grandmother’s front door opened, revealing a white-haired lady with a dimpled smile. Stepping outside in her bathrobe, she stood in front of a blooming flower bush with purple and pink petals. Behind her was an equally pretty, but younger, woman, who turned out to be his Aunt Blondell; with her light-brown complexion and almond-shaped eyes, there was a sweet sassiness behind her smile. Coming from both sides, the women hugged and kissed Malcolm as though they couldn’t believe that he was real.

“What about me?” Linwood asked.

“What about you?” his sister replied sarcastically.

The smell of breakfast slapped Malcolm the second he crossed the threshold. Sausage, eggs, grits, and coffee were already on the dining room table. The smell was intoxicating. He’d soon learn that his grandmother cooked constantly and the house always smelled of soul food. “Everything looks so good,” he said after washing his face and hands. As he sat down, he noticed his grandma staring at him. “You look just like your daddy and your granddaddy,” she said proudly. There was a joyful sorrow in her voice. “Linwood tells me you go to City College and you’re majoring in English and journalism.”

“Yes, ma’am. I want to be a magazine writer, though I’m not sure exactly what I want to write about.”

“Maybe you’ll write a story for Ebony or Jet one day. Wouldn’t that be something? But, the important thing is just to stay in school. Don’t be a college dropout like your daddy and aunt.”

“Mother, please,” Blondell hissed. “It’s too early for this.”

“I’m just saying. Y’all did good; it’s not like I’m not proud of you both. I’m just telling the boy to stay in school.” Malcolm felt the warmth of their familial fire as they snipped at one another. From his chair, he could see into the tidy living room, where above the fireplace there was a mantel full of framed photographs. He knew it would be rude to leave the table, but he vowed to look at those pictures before leaving at the end of the week.

Easter Service at Shiloh Baptist Church was special, with his grandmother (he’d decided to address her as Grandma after all) proudly introducing him to pastor and congregation. Church folks crowded around Sister Minnie, and it was obvious she had sway in that holy house as she basked in their praise. Back home, they sat down to a lavish Easter dinner at five pm. Minutes later the pastor stopped by, and his grandmother left them sitting at the table for a few. “Pastors always know when the food is being served,” Linwood joked, chuckling loudly.

“You and that laugh are going straight to hell,” Aunt Blondell said. After dinner she asked Malcolm to take a ride with her to the Piggly Wiggly. Linwood looked at him sternly, reminding him of the warning about questions. He got inside Blondell’s rusty Ford and she took him on a mini-tour of the town that included converted cotton plantations that were resorts and housing complexes, the old movie theater, and old East Side High School. “That’s where your father and I graduated from,” she said.

About two miles down the road she pulled into a driveway. Malcolm heard a pulsating bass booming. Outside the ride, he and Blondell followed the music until they reached a small bar called Lafayette’s that had a sign in the window advertising Easter Sunday Funk Nite. Looking through the bar’s window Malcolm saw Black men in colorful suits and gators dancing with stylish women.

Entering the joint, they sat at the bar. Blondell ordered a Johnnie Walker Black and lit a Newport. “Order whatever you want, it’s on me,” she said. “This is my old boyfriend’s place. We still friends though.” They both watched as young and old shook their groove thangs on the dance floor. “You know, I don’t know what your daddy was thinking, keeping you away from your family for so long. I’m so mad he never brought you down to meet dad.”

“I’ve grown accustomed to his procrastinating ways.”

“I’m glad someone has. Twenty years is a long time to find out you have a grown nephew,” she said and laughed. Opening her wallet, she showed Malcolm a grade school picture of his father sitting in his own father’s truck pretending to drive. “That was taken one time when dad was home for Christmas. Linwood loved climbing up in that truck. He always came out dirty, with some oil on him or something.”

“Were they close?”

“Not really. Men back then didn’t know how to be close with their kids. They worked hard, they put food on the table, but closeness with the children wasn’t part of the deal. Were you close to Linwood?”

“He took me to an amusement park once.” They both laughed. “At least he tried.” The DJ played the Bar-Kays classic “Holy Ghost.” Nodding his head to the bleating horns and frantic drum beats, Malcolm felt as though he was being baptized in the chocolate rhythms of Stax soul that flowed from the speakers.

“Would you like to dance?”

“With you?”

“Is there a rule against boogying with your aunt?” she asked. Gripping his hand, Blondell led him onto the floor. After the dance, she strolled to a payphone, called home so her mother and Linwood wouldn’t worry, and returned to the dancefloor. They stayed until last call.

The following day Malcolm was moving kind of slow. At noon he sauntered into the kitchen, where his grandmother was sitting at the Formica-topped table. There were pots on the stove over medium fires, the oven was on and he felt the heat. “Good afternoon, sleepyhead,” his grandmother said. “I usually don’t allow such late sleeping in my house, but since your aunt had you out all night, I figured you needed your rest. Would you like some coffee?”

“Yes, thank you.”

Pushing aside the newspaper, Minnie stood up and retrieved the silver percolator from the stove. “It should still be hot. You want cream and sugar?” After she finished fixing the cup of coffee with her grandma hands, she put the cup in front of Malcolm. One sip communicated instantly that it was the best coffee he’d ever had.

“Lunch will be ready in an hour. If you want a snack, I can make you some toast.”

“I’m good. Thank you, though.”

“Linwood mention wanting to go bowling tomorrow night. Can you bowl?"

“I’m not Bowling for Dollars good, but I can do a little something.”

Minnie put her warm hand on his forearm, and gently rubbed. “I know you’re a little nervous. We’re all a little nervous, but I want you to know that this is your home too. You’re welcome any time.” She smiled, winked at him. “And you don’t have to wait for your trifling daddy to bring you here either.”

“Yes, ma’am.” They both jumped a little when the stove timer dinged. “Boy, you too young to be as nervous as me,” Minnie laughed.

Three days later Minnie and Blondell stood outside in the crisp, chilly air saying their goodbyes. The Holiday Inn where the Amway convention was being held was two hours away, and Minnie packed them ham sandwiches. Malcolm promised to stay in touch, truly meaning every word. Before they pulled off, Malcolm glanced one last time at his grandmother and aunt, silently vowing to remember their faces forever.

About a mile down the road Malcolm muttered, “Damn.”

“What’s the matter? You forgot something?”

“I forgot to look at those pictures on the mantelpiece. Damn.”

“Well, now you have something to do next time you visit,” Linwood replied.

At St. Vincent’s Hospital it was impossible to sleep through the night. Someone was always checking vitals or running some test and had no problem waking you to get it. That second morning Malcolm awoke at dawn feeling anxious. When he was younger he was very shy and kept his talking to a minimum. Though that side of him had faded long ago, he felt it creeping back whenever he thought about his father.

Over the years there had been periods of estrangement, but that was always because there was so much he wanted to say that it was better to be silent. One of Malcolm’s problems when talking to Linwood was always trying to lighten the mood, as though a heavy conversation might mess things up. Even as a kid, he’d have a lot on his mind, but very little of it came out of his mouth.

At nine o’clock that morning he vowed to call Linwood in a half hour, but he kept pushing it back until it was almost two o’clock. After a few rings he almost hung up, but he paused when he heard his dad’s weak voice. He imagined Linwood in a similar bed with tubes and cords flowing from his body. “Hey man, how you doing?”

“Malcolm, man…how the hell are you, captain?” He had never heard so much enthusiasm in his father’s voice. “Evelyn told me what happened. That’s crazy. Did you see the guy?”

“Barely. It was dark. I saw the gun better than his face. I never had a gun pulled on me before.”

“What about all this New York City gentrification I keep reading about?”

“Criminals don’t move away, they just drift from one neighborhood to another. Have the doctors told you what’s wrong?”

“They’re still taking tests. It’s probably nothing.”

“I’m sure it’ll take more than nothing to make you piss blood.”

“Yeah,” Linwood whispered. “I don’t know.”

Though he didn’t know why he asked, Malcolm blurted, “How’s your mother?”

“My mother? She’s all right. Why?”

“I was just thinking about the time we went down Bennettsville. I regret I didn’t keep in touch with her and Aunt Blondell.”

“Oh, please. If anyone should have regrets, it’s me. I should’ve introduced you to your family years before I did. Did you ever learn how to drive?”

“You promised to teach me, so…no.” It was an inside joke between them and they both laughed.

“I’ve made lot of promises. Only kept a few.”

“So I heard.”

Malcolm and Linwood talked for an hour that day, and every day after for eight days. During each conversation, they touched on another part of that long-ago road trip. Linwood remembered the argument they got into over which one of them the flirtatious woman in the red Benz was smiling at; Malcolm recalled them stopping at the South of the Border tourist attraction. “God, that place, I’d wanted to go there for years,” Malcolm said. “I used to see their bumper stickers in New York all the time.”

He mostly remembered the giant Mexican stereotype Pedro that was their mascot, the huge sombrero-shaped restaurant, and a tacky souvenir store where he bought multicolored t-shirts and fireworks. “It started snowing that day. It was already mid-April. I was bugging out, because I thought it didn’t snow in the South. By the time we pulled out of the parking lot the flakes were big and beautiful and stuck to the windshield until the wipers cleaned them away. That was a good day.”

“It was a great day,” Linwood corrected.

“You’re right, it was a great day.”

That night Malcolm dreamed about his father. In the dream Malcolm was a little kid. He and Linwood were throwing a ball back and forth when suddenly it began to snow. They continued to toss the ball as the snow quickly accumulated. Malcolm blinked. When he opened his eyes fully everything was covered by snow and Linwood had disappeared.

The following day he called his father’s room and a strange woman’s voice answered. “He’s gone,” she said. For a few seconds Malcolm paused, already seeing Linwood stretched in a coffin and a church full of weeping women.

“Excuse me?”

“He’s gone. I mean, I’m sorry. I mean, he left this morning. His wife came and got him.”

Nervously, Malcolm laughed. “Lady, you scared the shit out of me.”

“I’m sorry, sir. I’m new here.”

Malcolm too was discharged later that day. His buddy Paul, whom he’d known since college, picked him up and took him home. He’d never been away for so long, and it felt good to finally be back in the same two-bedroom on the fourth floor that he and Lenore had chosen a decade before. It was in those rooms where they made love, threw dinner parties, celebrated birthdays, quit smoking, argued loudly, and held on to their marriage until her final day. “Being home is nice,” Malcolm said to Paul as he slowly lowered himself into his office chair.

He moved slowly for a few weeks, but soon Malcolm was working again: reading, researching, and writing. He tried to talk to his father more often, but he soon started falling behind. Still, he no longer held on to the anger he once had for Linwood. Or was it indifference? Whatever it might’ve been, their respective close encounters with death had changed everything, and he, before leaving the hospital, released those negative feelings as though they were a dozen black balloons filled with hatred and helium.

Linwood lived for another year, long enough for Malcolm to begin making plans to visit him and Evelyn for Christmas. “Will your mother and sister be there too?”

“They always are,” Linwood replied. “You know, Mom has dementia. She doesn’t remember a lot. Sometimes she barely remembers me.”

“It’s all right. I have enough memories for all of us.”

A week before Thanksgiving, Malcolm sat in his office staring out the window at the falling rain when his landline rang. Something in him stirred and, without even looking at the caller ID, he knew that it was his stepmom calling to tell him that Linwood was really gone. Closing his eyes, he took a deep breath and finally answered. The call lasted five minutes.

Outside, thunder and lightning crashed. Malcolm stood up, walked across the room to a shelf of CDs, and located B. B. King’s Greatest Hits. He popped out the disc, slipped it into the player, and blasted “Three O’Clock Blues.” Malcolm strummed an air guitar tribute but didn’t sing along until the last verse, when King wailed, Goodbye everybody I believe this is the end… yes, I want you to tell my baby, to forgive me for my sins.