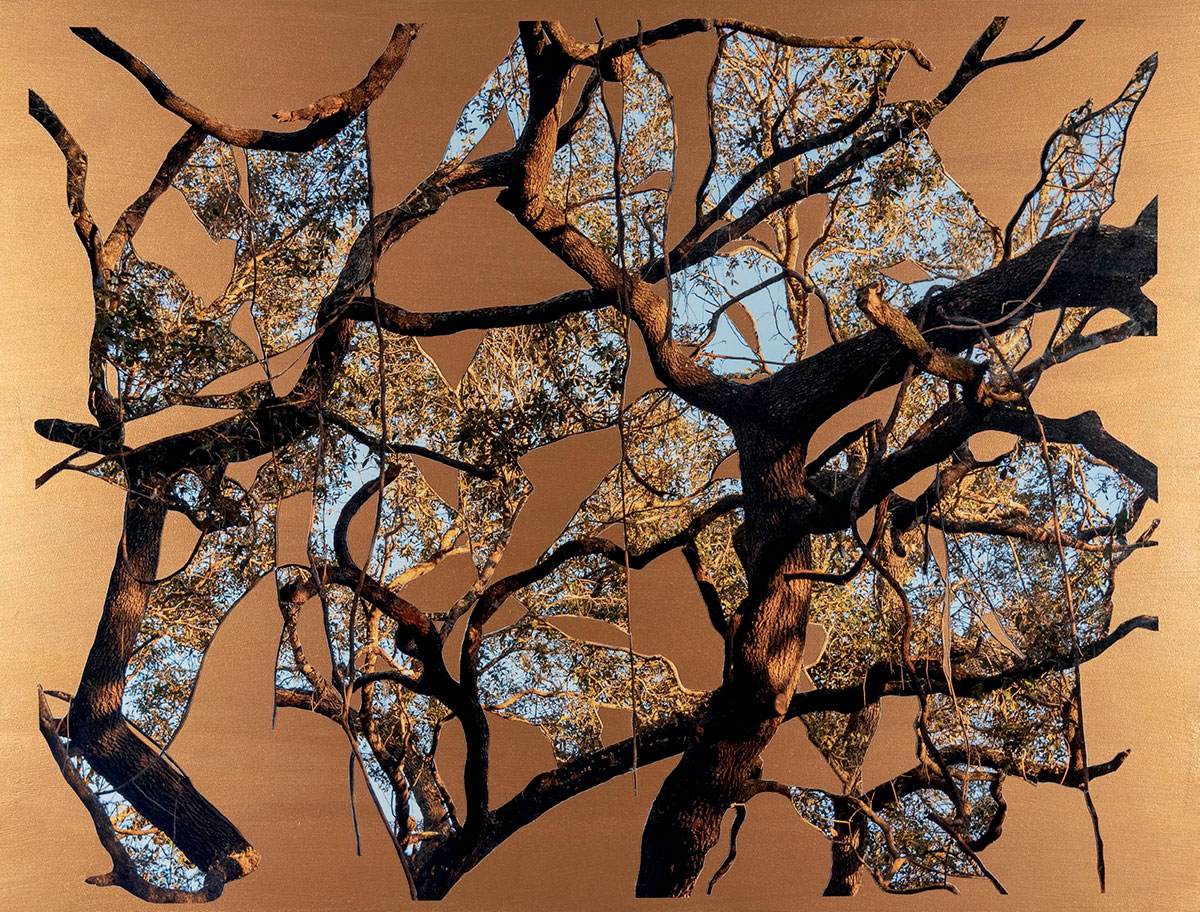

"Live Oak - Mondrian Style (Golden)," 2021, mixed-media collage, by Alysia Macaulay. Courtesy the artist and LaiSun Keane Gallery

Shaking the Tree

The gnarled history of Houston’s live oaks

By Paula Mejía

On a balmy late July morning four years ago, a team of arborists hauled away a resplendent live oak tree that had stood on Branard Street for nearly one hundred and fifty years. Tucked within the leafy Houston neighborhood of Montrose, a subversive, historically queer area now flecked with townhouses listed at half a million dollars, the mighty tree had framed the vast, emerald green lawn limning the Menil Collection—a beloved art collection, free to the public, known for its Magrittes and Indigenous art—and the Rothko Chapel, an octagonal, secular chapel ensconced with subdued paintings by the late Russian artist. The tradition of sitting under the Menil Park tree spanned generations of Houstonians. The act of resting one’s back against the supportive trunk and people-watching on the lawn or reading under a merciful sliver of shade blocking the blistering sunlight became an experience as formative as seeing the art inside the Menil itself.

Residents stood along the sidewalk in disbelief that day as a crew hacked away at the shrinking tree. The site where they had once picnicked away a long afternoon, played with their children, experienced first dates and last goodbyes had been unceremoniously dumped into a truck and driven away. “I never thought I’d feel sad over a tree,” lamented one Reddit user. “It was as if the tree itself was beckoning those around it to come and enjoy its respite from the heat,” wrote another.

For decades, possibly centuries, an incalculable number of visitors had mounted or leapt onto the tree’s ample branches, some of its arms dangling so low to the ground they nearly grazed the grass surrounding it. But years of hands grasping at the tree’s leaves and feet clambering for footholds in its trunk ultimately did not fell the Menil Park tree. Neither did the reality that some park goers used the branches as tightropes. It turns out the Menil Park tree had been worse for wear for a while, following a lightning storm that zapped the tree a decade prior to its removal. While the City of Houston Tree and Shrub Ordinance protects a handful of trees, including those the city council deemed historic and others located along a public right-of-way, the Menil tree fell short of any official designation to keep standing. So when city forestry officials paid the tree a visit in the summer in 2018, they ordered its destruction a few weeks later—hence the quick death following such a long life.

While bustling and beautiful as ever, the Menil Park lawn has since lost not only its welcome shade but also its crystallizing essence. The Menil Collection assured mournful residents that the museum would eventually plant another tree to assuage the loss, and that they would repurpose the tree’s wood for something in the future. But the promise didn’t make the blow any less significant for those, including myself, who had spent countless hours idling in the shade beneath the tree.

When I heard that the Menil Park tree had been chopped down, it felt as though a formative time in my childhood had gone with it. I also couldn’t stop thinking about the fact that such an old tree somehow hadn’t been uprooted by several centuries’ worth of hurricanes, floods, and other natural disasters. Not even Hurricane Harvey, the Category 4 swirl that ripped through Houston in August 2017 and killed nearly one hundred people, had managed to eradicate the tree. A flash of bad luck was all it took.

***

How does a live oak tree withstand gusts clocking in at one hundred and ten miles per hour, like those of 2008’s devastating Hurricane Ike? Or chunks of hail large and dense enough to leave deep craters in car roofs? Is it through sheer force of will or biology? “Tolerant of drought as well as soil salinity and salt spray, southern live oak is often categorized as a ‘tough plant,’” wrote Michael S. Dosmann and Anthony S. Aiello in a piece for the February 2013 edition of Arnoldia, a quarterly imprint from Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum.

The Quercus virginiana is a particularly stubborn species. Located within a thin strip of the southern United States, tracing the southernmost reaches of Virginia to the Rio Grande Valley in south Texas, the tree will grow anywhere its branches are able to spread. It won’t stop until age, as it does for all of us, eventually slows its momentum. A live oak’s branches tend to sprout not toward the heavens but, in a rather dramatic turn, downward and then in every other direction possible. While they can grow to about fifty feet tall, they are almost certainly much wider than that.

Live oaks also pack a particularly strong ecological punch. A single live oak tree is capable of sequestering roughly 268 pounds of carbon dioxide and absorbing a staggering 2,656 gallons of water per year. A recent study from the University of North Texas also found that the trees have a proclivity for curbing black carbon emissions in urban environments, acting as air filters of sorts. That’s why in the scientific community, the live oak has been dubbed a “super tree.”

The tree is not immortal, however. Diseases such as oak wilt, a fungus that essentially constricts the tree’s veins, can wipe out a hundred-plus-year-old live oak. Then again, its wood is so hardy that in the early nineteenth century the U.S. Navy maintained its own live oak forests to aid the burgeoning shipbuilding industry.

But as Andrew Furman wrote in this magazine in his 2010 essay “Big Wood,” some facets of the tree remain ambiguous. The origins of the name “live oak” itself are mysterious; the title may come from the fact that the tree appears to persevere through a brutal cycle of seasons without so much as shedding many glossy leaves. Or it might derive from the fact that its bark plays host to other varieties of flora, including ball moss and epiphytes—all of which are very much alive. As Furman also notes in his piece, a discomfiting truth exists about live oaks: Throughout the centuries, live oaks throughout the South have borne “silent witness to racial horrors,” as they sometimes were the site of lynchings in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

***

I hadn’t considered the live oak’s relationship to my hometown of Houston until I was thirteen, and I had to draw a few of these trees on March 5, 2005—a date I remember because it’s scrawled on the bottom right hand corner of the drawing. Around then my parents had whisked my younger brother and me from our home of five years in Corpus Christi, a mid-size community lining the South Texas Bay, to Houston. The move uprooted us from our friends, many of whom, like us, were second-generation misfits whose parents were part of the Latin American diaspora and tried their absolute best to hold it together. When my family and I, along with our two dogs, drove the four-ish hours northeast to settle in a massive and unfamiliar city, I suddenly knew exactly no one.

The cringe parade known as middle school started when we sputtered into Houston. I hated the city instantly. While I was no stranger to heat, an omnipresent film of humidity seemed to seep from every discernible place. The weather made it too hot to walk for long stretches most of the year, even under the shade of trees that lined parts of the street, so I would beg my parents to take me to Barnes & Noble. There I would flip through books and magazines I had no intention of buying until the store shuttered for the night.

After several years of being called “Carrot Top” (thanks to an unfortunate rendezvous with Sun-In the summer before sixth grade that had turned my voluminous brown hair orange), I’d found a place in Houston that I didn’t totally despise: a drawing class that I started attending once a week at the Glassell School of Art, an arm of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston campus. The drawing teacher, an eccentric man in his early fifties, mostly spooked us with scary stories about the building next door and taught us the difference between various graphite pencils.

One springtime afternoon, he gathered our class, telling us to bring our sketch pads and several pencils and to follow him outside. We walked behind him, away from the busy road, down several residential streets. The cityscape began to fall away. We edged closer to North Boulevard and finally stopped on a median. The long esplanade revealed rows upon rows of majestic live oak trees arranged in a diamond pattern. A limitless canopy of trees crisscrossed down the path of bricks, slotted in a herringbone pattern. The trees’ gnarled roots seemed to extend deep down and in every discernible direction. Their branches curled into the air and appeared, almost in a trick of the eye, to entwine with one another in the sky. The heavens felt barely able to contain them.

For a moment I genuinely forgot where I was. I wondered if I had fallen into Narnia, or a fantastical elsewhere plucked from one of the books I constantly lost myself in. I could not wrap my head around the fact that we were still in Houston, and that minutes ago, we were suffused by the whir of white noise and an infinity loop of traffic.

The spell was broken by my teacher. He explained that the point of walking over this way, to a neighborhood named Broadacres, was to learn about vantage points by drawing the trees that surrounded the esplanade. Peering down the median, he motioned toward a liminal space in the distance, where the trees eventually ended. We picked up our pencils and started to sketch thin outlines of trunks giving way to branches, leaves, sky. To me, the real lesson lay in the fact that these trees thrive in a place where a six-month-long summer season singes everything in sight, and what the sun doesn’t manage to do away with, the hurricanes very well might.

***

Over the next decade I put drawing aside, moved away from Texas for college, and started my career in journalism. My desperation to leave Houston eventually evolved into defending it whenever someone slighted it as a backwater town. It’s not an “isolated mudhole of a city,” as one state legislator in the nineteenth century grumbled. Houston’s not miserable; it’s misunderstood.

But even Houston’s fiercest advocates would say loving it requires embracing the fact that this place makes little sense. Consider that Houston is a metropolis overlaid on swamplands and coastal prairies, with five muddy bayous severing it and any semblance of zoning ordinances getting shut down in municipal elections—which is, in part, how you might find a mortuary on an ordinary residential street, and why some areas may be rife with trees while others are completely bereft of them. The frequent rain tends to fall sideways and torrentially. This isn’t excluding the hurricanes, heat waves, and once-in-a-generation freezes that are happening much more frequently. But for all this water, Houston isn’t exactly known for having ample public botanical gardens, parks, and greenbelts. If the city has one defining hue, it’s undoubtedly the distinctive, pallid gray tone of its miles of office parks, parking structures, and strip malls.

Yet what shapes the life of a Houston resident, more than its staggering scope—and greater than its colossal, vertiginous, six-lane highways, and far beyond the next impending disaster—is the sheer impossibility of this place. As writer Bryan Washington has put it, “In a lot of ways, the city can be defined by what it’s not—as an inverse of what lies beyond its municipal borders.” The foundation is a massive floodplain, yet what its community has managed to create here is astounding. The fact that this inscrutable city exists at all, and that more than two hundred and fifty new residents continue to stream in daily, is nothing short of a miracle.

Houston’s live oaks, which can live for hundreds and hundreds of years, share a similar moxie to the people who call the Bayou City home: By definition, they defy the disaster that, while an inevitable result of planting roots in this place, often minimizes what it means to live here.

***

Houston’s first population boom began a while ago. When the city was founded in 1836 following Texas’s independence from Mexico, it consisted of a handful of blocks around the White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou. As the city began annexing surrounding lands in the late nineteenth century, its population grew in tandem, reaching forty-four thousand in 1900. When the city established the Houston Ship Channel and the Port of Houston in the 1910s, the more robust network of railways and the port caused a further uptick in new residents. By the 1940s, Houston’s population had increased tenfold. Four hundred thousand residents and counting meant more housing was needed.

The Houston Post classifieds from that era brim with enthusiastic advertisements for new subdivisions. One post in the February 10, 1924, paper hawked three recently developed neighborhoods to prospective buyers—Broadacres, North Edgemont, and Edgemont—as “the highest class addition in the city of Houston.” Ranging from $30,000 to $50,000, the homes on Broadacres’ thirty-four acres boasted “ornamental lights and shrubbery on North and South Boulevard.” Architect William Ward Watkin, the first chairman for the Department of Architecture at the nearby Rice University, laid out the plans for the subdivision, which featured twenty-six secluded homes arranged around a horseshoe-shaped boulevard with staggered rows of live oaks. Coupled with the mansions surrounding them, the trees of Broadacres “conferred legitimacy on Houston’s elite as civic leaders by framing them in settings of exceptional beauty and spatial coherence,” wrote architectural historian Stephen Fox in The Country Houses of John F. Staub.

The development of tree-lined neighborhoods such as Broadacres collided with the City Beautiful movement, which coalesced en masse around the United States near the turn of the twentieth century. Following Daniel H. Burnham’s “White City” unveiling at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the park planning of the Olmsted family, middle-and upper-class residents in cities across the nation created civic organizations dedicated to erecting and maintaining public parks and gardens with lush, verdant lawns—not unlike the estates of English and French nobility of generations past. A jolt of civic pride took root along with swathes of flora and fauna. “It was a time when there was a lot of gravitas into bringing green space into cities,” Vivek Shandas, a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University, tells me. “And the places where the green spaces ended up were often the ones that had space, physically, and...a voice for attracting green spaces.”

As the mighty Broadacres live oaks matured and their canopies expanded over the ensuing decades, the trees became a spectacle that overshadowed the stately homes surrounding them. By 1980, the Broadacres esplanade had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the New York Times would later proclaim that “to stand at the foot of South Boulevard in Houston is to look down what is perhaps the most magnificent residential street in America. Staged rows of soaring live oaks form the vaulted arches of a great Gothic cathedral over a grassy esplanade.”

The trees along the Broadacres esplanade have since become a favorite destination for joggers and Houstonians walking their dogs, as well as families celebrating milestones: graduations, birthdays, weddings, quinceañeras. But in recent years, the Broadacres median has also illuminated tensions between private and public space in a city with limited green areas. In 2017, the city decreed that the Broadacres median was a public right-of-way after the neighborhood HOA president Cece Fowler put up $1,300-worth of signs forbidding photo shoots along the esplanade. Two years later, a resident confronted a young family taking photos of their one-year-old baby in front of the live oaks, as well as a family taking their daughter’s prom photos. Some Broadacres residents have claimed that the trees’ many admirers have ruined the community at their expense: While the esplanade is public property, the grass surrounding it is not.

The larger neighborhood of Boulevard Oaks, where Broadacres sits, is bordered by the 59 freeway to the north and Bissonnet, a major thoroughfare, to the south. During the same decade the Broadacres esplanade received its historical designation, clusters of trees had withered and died within the greater neighborhood of Boulevard Oaks due to a lack of irrigation, as Evalyn Krudy, former chair of the area’s tree committee, tells me.

A group of Boulevard Oaks residents decided to restore the trees in the area by raising the funds themselves. They helped kickstart a nonprofit, Trees for Houston, founded in 1983, as well as a pilot program where they knocked on doors on one of the subdivision’s streets (1600 block of Milton Street), asking residents if they wanted a tree planted in their yard. From there, residents “saw the success of that one particular block” and said “‘Hey, you know what? I want a tree this year,’” Krudy recalls. “And it just caught on. People saw the transformation and were excited by it and wanted to participate.”

Krudy estimates that it took the tree committee roughly sixteen to eighteen years from the time of its founding to plant trees in the entire neighborhood of one thousand two hundred residences, street by street. All told, that shakes out to about fifteen thousand trees, including live oaks, and she estimates that it’s cost at least $400,000—a sum raised by residents of the area. “Since then we’ve planted and have just been filling in where trees have died or get mowed down,” Krudy says, hardly mincing words, “due to poor zoning and lack of zoning in a city of Houston permitting department that doesn’t seem to have the best interest of trees and neighborhoods and clean air in mind.”

***

“When trees are found in a neighborhood, there was a deliberate effort to place those trees in those neighborhoods,” says Shandas. Not every residential neighborhood in this metro area of seven million has spectacular rows upon rows of live oak trees, nor the means to mobilize and raise funds to promote large-scale planting, nor the space needed for the large trees’ root systems to fully entrench themselves into the ground. The architecture of live oaks is very much entwined with the way Houston’s planning, development, and growth have unfolded—and the placement of these trees has been deeply rooted in inequality.

Since 2018, Shandas and a team of researchers have widely distributed research-grade sensors to different communities across the United States to map heat and humidity levels across neighborhoods. “At least in a dozen cities or so, I started noticing a pattern where places that were identified in many reports as having intergenerational poverty, food deserts, lower levels of green space were consistently hotter than [areas that] were invested in over the decades,” Shandas says.

At first, he couldn’t pinpoint the root of the problem. His colleagues theorized that the pattern could be traced to “the luxury effect,” which Shandas describes as wealthier communities’ ability to “buy trees, take care of their yards, [and] lobby potentially in their neighborhoods,” whereas “communities that are lower income, communities of color, are not able to engage in those ways.” That’s especially true of Houston, a city with opaque zoning laws and no regulations stipulating where trees must be planted: Where one area’s residents can raise funds and opt to plant a tree, there’s no ordinance stating that another neighborhood must do the same—and it’s up to community organizations, nonprofits, and residents to raise the money for these efforts. That lack of zoning reality is why, as Shandas puts it, Houston can “have a very lush urban neighborhood, and immediately, two blocks away, have something that looks very, very different in terms of land use.” Shandas wasn’t convinced the luxury effect was the only factor involved, though. “I had a sense that there had to be a systemic issue at play here,” he recalls.

One year earlier, in 2017, the University of Richmond created a digital archive of maps from the 1930s through the 1960s, when redlining was a federally codified and racist policy that prevented Black residents in certain “declining” areas from pursuing home loans, confining them to parts of the city that were deemed unworthy of investment. When Shandas’s team overlaid those archived digital maps onto those of 108 cities in the United States, they found that redlined neighborhoods had the hottest temperatures of those respective urban regions, sometimes with a fifteen- to twenty-degree difference compared to shadier areas. “The areas that were graded ‘A’ and ‘B’ [‘best’ and ‘still desirable,’ respectively] sometimes had several orders of magnitude more green space than their redline counterparts,” Shandas says. This form of environmental racism also comes through in the way that “gray infrastructure,” including the likes of big box stores and highways historically built with heat-retaining cinder block and brick, was often erected in redlined neighborhoods. The legacy of redlining undoubtedly has contributed to the propensity of urban heat islands.

Sixty-nine percent of all Houston neighborhoods were deemed “hazardous” or “definitely declining” when redlining designations were made in 1940, tellingly, when an overwhelming majority of Houston’s then 384,514 residents identified as “native-born white.” In a study of their own, the organization Houston Harris Heat Action Team (H3AT) dispatched eighty-four volunteers to map heat and humidity distribution across Houston on a single day in early August 2020, typically the most brutally hot month of the year. In certain pockets of the Third Ward—a historically Black neighborhood just south of downtown that’s home to the University of Houston, deemed “hazardous” by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation back in the ’40s—temperatures reached ninety-eight degrees. Several blocks away, near a street named Live Oak, an area formerly declared “desirable” was four full degrees cooler.

***

The architecture of live oaks is very much entwined with the way Houston’s planning, development, and growth have unfolded—and the placement of these trees has been deeply rooted in inequality.

Several years ago, Deborah January-Bevers took a boat trip down the Houston Ship Channel—an area that stretches from the city’s southeastern side to the Gulf of Mexico, not exactly known for its greenery. January-Bevers, president and CEO of Houston Wilderness program, was surprised to see a bevy of green space lining the port, ideal for large-scale tree planting. The organization later started working with the Port of Houston and the economic port alliance to create an initiative: to plant a million trees by 2030 along the twenty-five miles of the ship channel.

When Houston Wilderness ranked tree species by the rate at which they absorbed toxic elements, live oak trees came out as the top “supertree,” January-Bevers says. Their hardiness was also a factor. “They are the toughest tree; they will grow anywhere,” says Krudy. “Yes, you can kill them. But once they get old and established, that tree is gonna stay.”

Houston Wilderness has since been brought on to help strategize the planting of over four million trees with the City of Houston. Two years ago, the city unveiled its “Resilient Houston” initiative, which aims to help it weather challenges to come in the future. One of its eighteen goals, spanning public transportation and environmental concerns, involves planting 4.6 million new native trees by 2030. The ambitious plan will “focus efforts in areas with the strongest urban heat island effects, air pollution issues, environmental injustice, inequitable tree canopy cover, and a high concentration of pedestrians and bicyclists who would benefit from shade.”

The data backing the resilience initiative is a sobering read. It details how the city has lost critical levels of tree canopy—a cover that helps to curb heat and provide life-saving shade to residents who take public transportation or walk to get to where they need to go. According to one study cited in the report, Houston lost so much tree canopy between 1972 and 1999 that it led to 360 million more cubic feet of stormwater during a peak storm event. And about a decade ago, a record-breaking drought wiped away 301 million trees throughout Texas.

But tree planting isn’t as easy as digging a hole and hoisting a tree into the ground, particularly in disadvantaged communities. “When an area is disinvested in,” Shandas says, “it tends to attract a lot of the development patterns that seal up the ground and prevent even surgically placed trees to be planted in those locations. You have to tear up concrete or asphalt to get the trees into the ground.” Furthermore, disinvested areas often have smaller medians that don’t allow for larger-scale tree planting. Then there’s the matter of Houston becoming the Texas city that’s most rapidly gentrified in recent years. When neighborhoods undergo radical development and beautification efforts, bolstered by an influx of capital, it’s often a sign of gentrification to come—or one that’s already in process. A study released by the Pacific Northwest Research Station in 2021 “found that the number of trees planted in a tract was significantly associated with a higher tract-level median sales price” over a period of six years in Portland, Oregon.

***

An arborist from Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, an educational agency that studies the intersection of agriculture and health, recently told me about two live oaks I’d never heard of in Houston: a pair of seismic trees purported to be over four hundred years old. They currently sit on a sizable patio behind a Beck’s Prime franchise, across the street from a superb strip mall karaoke joint on a particularly busy stretch of the city. Apparently one of the restaurant’s founders fought to save the trees; they formerly stood behind a chain-link fence. Even though my father had just come off a long shift at work, he agreed to join me one morning so we could see the trees together.

The restaurant hadn’t quite opened for the day, but the smell of smoked meats wafted into the sprawling yard. We approached the trees gingerly in this unusual commercial space, not quite a public park but hardly a private residence. When it seemed clear that, yes, we could be here, we made our way to the base of the first one. It was astounding, larger and more majestic than I’d ever thought a tree could be. The colossal branches seemed prehistoric, their heft held up by supports and cables. The simultaneous awe and reverence I felt was not unlike the experience of sitting under the felled Menil Park tree. Then, my dad did something I’d never seen him do before: He went up to the tree, and rested his head and his hand on it for a long moment.

It’s notable that the business opted to protect and maintain the trees instead of razing them, especially at a time when public space is so contested and development is happening at such a clip. Yet it shouldn’t take an arborist to let residents of Houston know that these magnificent trees exist, or that they’re attached to a commercial enterprise. However gnarled their history and implications may be, if these trees sprouted up throughout more of Houston, it would transform the city in practically every measurable sense.

While visiting my parents in Houston last year, I found the drawing of the live oaks that I sketched on that March afternoon nearly two decades ago along the Broadacres esplanade. Taken outside their context, they look like spindly little shrubs on the page. I can’t fully see the depth of meaning the live oaks contain, their complications, the weight of their presence—and absence. A tree, after all, is never just a tree.