Cavities and Debris

By Melody Moezzi

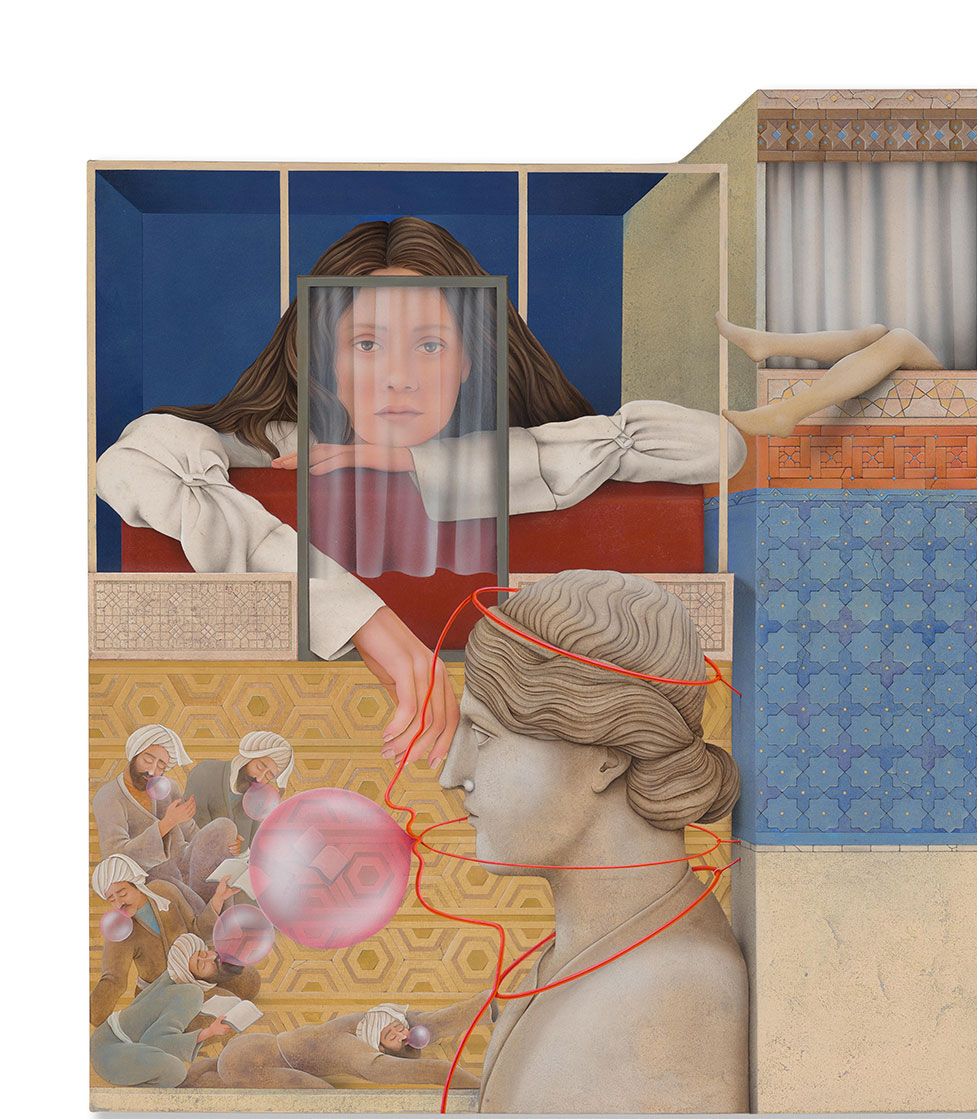

"The Touch," 2019. Acrylic on canvas stretched wood panel, by Arghavan Khosravi. Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York

I should’ve found a new dentist years ago. The fact that Dr. Patel has stopped giving me his signature scratch-and-sniff stickers and started calling me “the Elder” might have been enough to force others out by now, but not me. We’ve been through too much together: dozens of cleanings, six fillings, two extractions after an unfortunate encounter with the bottom of a swimming pool, and one nitrous-fueled hallucination wherein the toucans on the ceiling flew down to greet me. And history aside, where else am I going to find a free Pac-Man machine in the waiting room?

So much is my penchant for Pac-Man and my loathing for change that, at thirty, I am still seeing my pediatric dentist. But Dr. Patel didn’t meet me as a full-grown adult earning a doctorate in biochemistry. He met me as a miniature refugee fleeing the Iran-Iraq War and landing in the buckle of the Bible Belt. Only a week after we left Tehran, the aforementioned swimming pool face-plant suddenly made dental care a high priority for my family, and Dr. Patel was the only dentist in town who worked weekends. His was the first brown face I encountered in any position of authority in America. He bore a striking resemblance to my favorite uncle, who had just died in the war, and he didn’t care that we barely spoke English. So of course, it’s possible I grew a little too attached. It’s also possible I’m digging way too deep for excuses. Whatever the case, I feel embarrassed to be here, but I also feel reassured by the faded jungle-themed wallpaper peeling at the seams. Shouldn’t I be allowed to stay at least as long as the wallcoverings?

Such is the mental flotsam whirling about my head as I level up at Dr. Patel’s ancient arcade table. Just then, from the television bolted to the ceiling, a giddy meteorologist interrupts Judge Judy to report tornado warnings. My eyes drift up to it for a second at most, but by the time they dart back down to the Pac-Man machine, it’s too late. Death is inescapable. Trapped in a corner between two ghosts, orange to my left and red below, I collide with the latter and disintegrate on contact. Sirens and Dr. Patel’s voice muffle the sound of my virtual demise as reality sets in: Several tornadoes have already touched down around us. We aren’t safe here.

“Follow me,” says the sweet old man who should be a waning memory, a charming relic of my childhood graciously bequeathed to future generations. This whole scenario might make sense as a bizarre dream, with me playing the part of a living anachronism. But as an actuality, it’s absurd.

Here is Dr. Patel, a fixture from my past dragged into the present courtesy of my epic indolence and misoneism. And here am I, a grown-ass woman following him, his staff, three children, and their moms into a basement I never knew existed.

Small, oblong, and bare—with concrete floors, fluorescent overhead lights, white walls lined with brown cardboard boxes, and a solitary drain at the center—the basement reeks of bleach and bubble gum.

Following Dr. Patel’s instructions, we push aside packages to make room for our bodies, sitting on the floor against opposing walls. I head to a far corner, maximizing the distance between me and the others, moving a carton labeled PATIENT TOWELS, and quickly taking its place against the wall. Behind this box and sandwiched between two others (SALIVA EJECTORS and ORAL EVACUATOR TIPS), I long to disappear.

Even the most mundane small talk will likely force me to explain why I’m here. So I keep quiet and out of sight, sinking into my corner sanctuary, hugging my knees close and tight. Together, side by side, my patellae create a cradle for my chin. A fit so seamless it has me imagining all these bones fused at some point in fetal development, like continents once joined, yet destined to drift apart, a human Pangaea divorcing itself.

Soon my chest fills with panic. Hoping to extinguish it, I try a trick a firefighter once taught me: shifting my focus away from the racing thoughts in my head (What if Brazil crashes back into West Africa? What if this tornado flattens all of central Georgia? What if we never get out of here?) and toward an object in my immediate vicinity (the patient towels). Fixating on the box, I read everything on it. The words are as random as they are irrelevant to me, yet each one delivers more comfort than the last. And with that comfort comes clarity, a flood of revelations flanked by nonsense, the latter somehow bringing the former into focus:

DARBY DENTAL SUPPLY. Grow the fuck up. QUALITY CERTIFIED. Leave Dr. Patel. PATIENT TOWELS. Finish my PhD already. ECONOMY. Move out of Macon. BULK. Procure new employment that doesn’t involve torturing rodents. 2 PLY PAPER. Quit dating assholes. 1 PLY POLY. Start painting again. PLASTIC BACKED. Stop skipping breakfast. ABSORBENT. Hydrate. STRONG. Exercise. SOFT. Cease freeloading on my parents’ mobile plans. 18" X 13". Learn to cook. (45.7 CM X 33.0 CM). Do my own damn taxes. 500/BOX. Find a general dentist.

Stunned by this strange string of Darby-Dental-Supply-inspired directives, I resolve to follow them all. To seal the deal, I close my eyes, take in a deep breath of bubble-gum-bleach, and exhale slowly, whispering a prayer: bismillah.

“Bismi-what?”

Startled, I open my eyes to find a little girl standing before me. Where seconds before there was nothing, just empty space between my body and the patient towels, now there is this pintsized human staring at me.

Her head is draped in a mop of tight red curls framing a face full of freckles, and her enormous green eyes bulge defiantly out of her skull. She wears a faded blue cotton dress with multicolored buttons in the shape of various farm animals running down the front. Her stomach protrudes just enough to give prominence to the purple cow. She is missing one of her shoes but doesn’t seem to mind. Stepping forward, she comes in close and looks me square in the eyes, the way only children have the nerve to do.

“Bismi-what?” she repeats.

“Bismi-llah,” I reply.

“I don’t know that word.”

“You don’t need to. It’s not English.”

“Is it Spanish? I watch Dora, so I know some Spanish.”

“No, it’s Arabic.”

“What’s it mean?”

“In the name of God.”

“Why’d you say it?”

“It’s just a prayer I say before starting something—like before I eat or leave the house or drive or take a test. Stuff like that.”

“Like ready, set, go?”

“Sure. Why not?” I reply. Desperate to exit this conversation, I lift my head above the boxes and scan the room for this kid’s mom.

“I’m Katie. What’s your name?” she asks, holding her hand out to shake mine like this is old hat to her, like she sneaks up on strangers in basements every day with the express intent of staring them down and shaking their hands, like she is living in some Peanuts special where parents are irrelevant.

“I’m Ziba,” I say as I shake her hand. “Where’s your mom?”

“She’s over there,” Katie replies, pointing to the opposite corner of the room.

I follow the direction of her pudgy finger with my eyes to a thin blond woman holding a stuffed Big Bird on her lap. She looks wan and weathered, her head cocked so far to the left that it seems on the brink of snapping. She is beyond sleep, mouth agape, harsh fluorescent light reflecting off a string of drool inching toward Big Bird’s beak.

“She's real tired,” Katie explains. “Stephen says I make her tired, but that’s not really true. She’s sick. Not like she’s-gonna-die sick, but like when you’re always tired and fall asleep when you don’t want to. That kind of sick.”

I try to make eye contact with the two conscious mothers in the room, hoping they will sense my total lack of maternal instincts, pity me, and rush to scoop Katie up. No such luck. I’d have to move the box of saliva ejectors for the other moms to see us. But I’m so repulsed by that label alone—unable to imagine even speaking those two words in succession without gagging—that I can’t bring myself to handle the box. What if, at the exact moment I pick it up, a tornado crushes us all? My obituary could read “Graduate Student Crushed Beneath Box of Saliva Ejectors.” I can’t risk it.

“Have you ever been sick?” Katie asks.

I want to say I’m sick right now, but I say “yes” instead.

“Are you better?”

“Sure,” I reply. “It was never anything serious: just colds and flus really—”

“Can I see that?” she interrupts, bored by my trivial viruses. She is leaning out from behind the patient towels and pointing at a man across from us.

“See what?”

“The magazine that man is reading. Please ask him for it, Ziba!”

“You ask him.”

“You’re bigger. He’ll listen to you.”

I lean over to get a better look. He isn’t part of Dr. Patel’s staff and doesn’t have a kid in tow, so I’m just as confused as someone else would be looking at me prior to Katie’s arrival. But he is at least fifty, and by Dr. Patel’s own chronic telling, I am his oldest patient. Just then, the man straightens his back against the wall, revealing a UPS logo above his left shirt pocket, and the mystery is solved. He looks affable enough and I’ve never had a bad experience with a UPS courier, so I get up and give in to Katie’s demands. She follows closely behind.

“Excuse me, sir,” I say softly so as not to wake anyone up.

Katie’s mom has set the tone for this afternoon without trying. Apart from Katie and me, the UPS guy, and Dr. Patel (who appears to be doing paperwork), everyone else is either fast asleep or well on their way. Most knees have been released, and despite the sirens, people seem oddly calm.

The other two patients—tweens with the trials of impending adolescence airing brutal previews on their faces, the girl’s caked in glitter and the boy’s coated with cystic acne—are lying on their mothers’ laps. Both moms hold up their own heads with one hand and rest the other on the heads of their respective offspring. The secretary and hygienist sit serenely against the wall behind Dr. Patel, presumably asleep as well, muted shadows.

“Would you mind lending your magazine to my friend Katie here?” I ask.

“Can’t you see that I’m reading it?” he snaps.

“I’m sorry, Katie. The grown man won’t let you see his magazine,” I tell her, just loud enough for him to hear as we head back to our corner and sit down. He then gets up and walks toward us, the magazine (which I can now discern as Time) in hand.

“How old are you?” he asks Katie sternly, squatting down so they are face to face. I immediately stand up. It won’t be hard to throw him off his center of gravity if he tries to touch her, and I am ready to do it. Despite my general aversion to children, this one is growing on me.

“Six and a half. How old are you?” she responds, unperturbed, reminding me of myself at that age. I’d already survived a revolution and was living in a warzone, so it took a lot to scare me back then. I was raised to never let anyone hurt or intimidate me—at least not without a fight. Political turmoil aside, Katie seems to be the product of a similar upbringing.

“I’m older than you, and as a person who has been on this planet for quite—”

“Could I pleeease see your magazine, sir? I’ll give it back,” she interrupts. He looks at me as if I am to blame for this. I feel a little sorry for him, crouched down on the concrete like an oversized gopher, now looking up at me with his beady blue eyes, but I’m not about to take the blame. I have no interest in his periodical.

“Come on,” Katie continues. “Don’t be such a meanie. Didn’t they teach you that you’re supposed to share?”

Defeated, Gopher drops the magazine onto the floor next to us, rolls his eyes, and heads back to his side of the room. I’m baffled by how quickly she got him to cave. Growing up in Iran and even here, I’d never have spoken to an adult like that. To this day—bound by the endless intersections of Southern and Persian hospitality—I wouldn't dare. But Katie is brave and shameless. She proudly hands me the Time.

“I didn’t want this,” I say.

“But I can’t read so good yet. You have to read for me. Pleeease, Ziba.”

The magazine is several months old, but the world hasn’t changed much. I probably should decline Katie’s request based on the cover alone: a shirtless, hooded, emaciated prisoner, arms tied behind his back—presumably one of the Abu Ghraib detainees—with the words “Special Report” and “IRAQ: HOW DID IT COME TO THIS?” printed above his head. But having no children of my own and zero desire to create any, I suck at discerning what is and isn’t appropriate for them. Both of my sisters have kids, and over the years, I have repeatedly gotten in trouble for exposing them to too much too soon, from Gray’s Anatomy to Public Enemy. Point being, I should know better by now, but I don’t.

“You really want me to read you Time? It’s not like Dr. Seuss. It’s boring and depressing.”

“Do you have Dr. Seuss?” Katie pleads.

“No,” I concede.

“Then Time! Please read it. Pretty please with a cherry and sprinkles on top?”

“Fine. What do you want me to read?”

Katie slides in close beside me and takes the magazine from my hands, flipping to a story with a photo of George W. Bush grinning like a maniac while shaking some general’s hand. On the opposite page is a bloodied soldier lying on the ground next to a tank.

She immediately points to it, nudging my elbow with hers: “This! Tell me what it says.”

So I begin reading, assuming she will quickly realize how tiresome and confusing it all is and make me stop. But she doesn’t. Until—nearly a third of the way through the article—I read the word Fallujah. She grabs my arm and looks up at me with her big emerald eyes.

“Have you been there?”

“Um, no, Katie. It’s super dangerous. You don’t wanna go there.”

“But the name: Fa-lu-ja. It sounds so cool. Like a circus or a cartoon or something. Even if bad stuff happens there, it can’t be all bad.”

“Of course. I’m sure it’s nice normally, but right now it’s a huge mess. There’s a war going on. It’s not safe.”

“I know,” she says, staring at her shoeless foot. “My brother Stephen died there.”

Is she serious? I think to myself. Then: Of course she is serious. She’s six. What the hell were you thinking reading this to her?

All I wanted was a filling, and now here I am stuck in a basement under a tornado, traumatizing a total stranger, a child, for no good reason. Unlike a filling—painful for a few minutes, but ultimately advancing us to victory in the battle against tooth decay—there is zero upside here. It’s far too late to get out of this mess now, and even if it weren’t, there is nowhere to go.

Are you even supposed to tell kids that young when people die? And if so, are you supposed to tell them where and how? It just seems like Katie knows way too much already, but then again, I guess I did too at her age. I always found it strange how the same people who would tell us kids not to fight with one another would then go off to war to kill each other the second they were grown. I close the magazine and lay it on the floor facedown, remembering how tightly Uncle Hamid hugged me the last time I saw him, like his body knew he’d never return from the war even as his words tried to convince me otherwise.

“I’m so sorry that happened to your brother, Katie.” My immaturity and carelessness have no doubt further wounded this innocent girl, and I hate myself for it. But she doesn’t look sad or distraught. She just keeps staring at her unshod foot: her sock, that pale pink that sinks in when you accidentally throw in a red with whites.

“Why? It’s not your fault,” Katie says calmly, sliding a tiny turquoise crucifix back and forth along the silver chain around her neck. “Do you have a brother?”

“No, just a couple sisters.”

“I only had Stephen; now it’s just me and Mom. She’s okay, but since he died, she doesn’t play with me as much—and she sold our trampoline. Do you have a trampoline?”

“No. I’ve actually never been on one.”

“Oh, Ziba, they’re so much fun. You’ve gotta try it,” she gushes.

Katie has somehow managed to jump from her dead brother to trampolines in mere seconds. I’m grateful though, as I’ve now exceeded my max quota for blood and gore for the day; trampolines I can tolerate. But Katie is already bored with them by the time I come to this conclusion.

Grabbing the magazine in front of us, she stands up, turns around, and then sits back down to face me, lotus style, her back against the patient towels. Without a word, she calmly and deliberately proceeds to tear the Time to shreds. Gopher soon notices from across the room and jets back to us.

“Tell her to stop!” he whisper-yells at me. Tears are now streaming down Katie’s face, but she is silent and still. Not a single sniffle or even a chin quiver. Just a flood of tears.

“I promise I’ll buy you another copy. Just please, give us a minute,” I tell Gopher as I wipe Katie’s cheeks with my thumbs, holding her head in my hands.

“No way, lady! That’s my magazine. It’s not from the waiting room. She said she would give it back. Now look what she’s done to it, what you’re letting her do to it.”

Standing behind Katie, Gopher can’t see her face. I’d like to think that if he could, he would shut up right quick and crawl back into the sad hole whence he came, but I doubt it. He saw me wipe her tears, so he must know something is wrong.

Having obliterated the magazine in her lap, Katie gathers the pieces in her skirt, turns around, and empties the mess onto Gopher’s faded brown work boots. His face turns so red so quickly that it looks as if his blood might actually be boiling. Still, he mercifully says nothing as he wrings his hands and returns to his side of the room.

But this time, through no act of his own, Gopher doesn’t walk back as just another trifling human. Rather, he does so—thanks to Katie—as a monument in motion, scraps of copy scattering across the concrete with his every step, dispersing devastation in all directions, disaster confetti. Were we in Manhattan, Katie could revive and direct this same scene nightly, call it performance art, and charge admission. But being in Macon, I know there will be no repeat performances, so I savor this one.

“I feel better,” Katie says. “I didn’t want to be mean, but it felt good to tear something up. You know?”

“Sure. And look at what you made,” I say as she sits back down beside me and we behold Gopher’s retreat. She has stopped crying and is resting her head on my arm. “You see those snippets of paper flying all over the place? It’s so pretty, like moving art.”

“Art? It’s a mess though. When my mom wakes up, I’ll be in trouble. She’ll make me clean it up for sure.”

“All the best art is a mess that gets the artist into trouble,” I say. “But I have a mom too, so I get it. Why don’t you wait here while I go pick up the pieces?”

But before Katie can answer, the lights go out, and my mind regresses twenty years in an instant. At ten, in Tehran, tornadoes were nowhere on my radar. Back then, when the lights went out, it wasn’t wind we worried about. It was war.

So I do what my parents trained me to do in the event of an aerial bombing: I find a basement—convenient given I’m already in one, albeit twenty years later and across the Atlantic. But trauma leaves no room for daft delineations around time and space. Here, reflex reigns. Just as my pupils take the darkness as a cue to dilate, my psyche takes it as a cue to negotiate. Thus, with neither thought nor effort, I proceed to step two of my childhood civilian military training: desperate devotions.

Filled with a fervor only explosives can evoke, I pray with the passion of a pilgrim crawling to Karbala on Ashura. These aren’t the prayers I used to speed through five times a day like an annoyed auctioneer selling my soul for a few more minutes with a jump rope or a pogo stick.

These are the prayers I extend and enunciate like a dread-filled delinquent knowing this might be her last chance to repent for every prayer she has ever skipped or sped through. My loud, elongated Qur’anic verses fill the basement, waking everyone up but me.

As our eyes slowly adjust to the dark, Dr. Patel and several others, including Katie’s mom, take turns asking me what’s wrong, attempting to comfort me, to coax me back into the present. But none of it registers, so I keep praying.

Unsurprisingly for Macon, there are no other Muslims in this basement. But there is Katie, and as of twenty minutes ago, she knows bismillah. As I stand, bend, kneel, and prostrate, she does the same, holding my hand in hers, our limbs connected like two electrons in a covalent bond. All the while, she keeps repeating the only prayer she knows I know too—simple, selfless, and sacred—over and over again. A tiny, accidental shaykha clearing out decades-old psychic debris, she fills the incandescent emptiness with a single word, spoken in succession and solidarity. Bismillah.

Minutes later, when the lights return and the sirens cease, Katie’s zikr persists, carrying me back to the twenty-first century intact. Ready. Set. Go.