A Tale of Two Songs

Love lost, love found

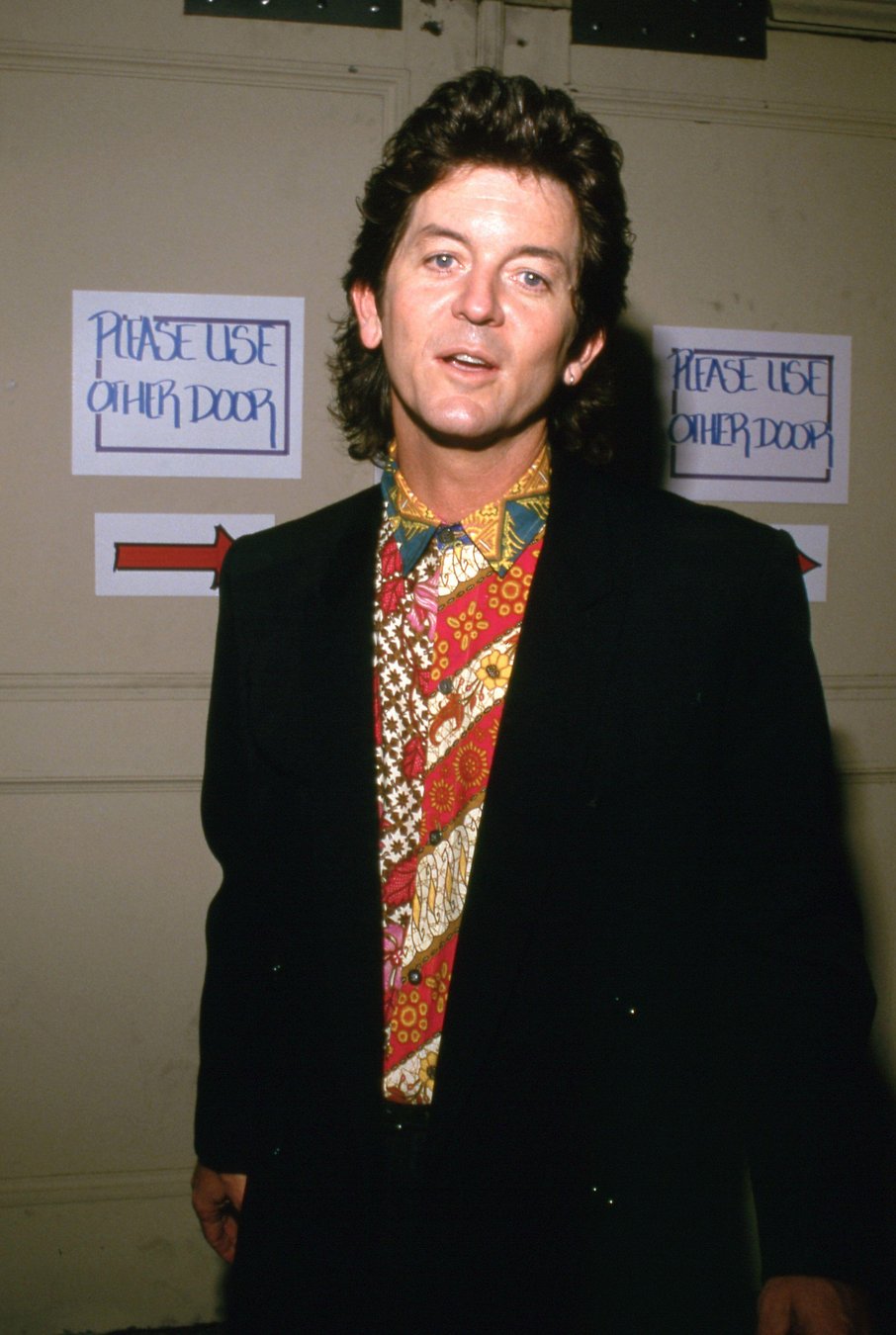

By Rodney Crowell

Photograph © Ralph Dominguez/MediaPunch/Alamy

My wife of twelve years fell instantly in love with the New York–based record producer I’d invited to dinner at a restaurant near our home in Nashville. Or at least, that’s what I see in hindsight. If I was oblivious to the sparks flying across the table that fateful night, it’s because I, too, was beguiled by our guest. Having caught wind of his talent, I’d flown up to New York to enlist his help with an album we were starting work on the next day.

I remember not appreciating at first the integrity exhibited by my soon-to-be-ex-spouse as she alerted me that her feelings for my new friend and collaborator were strong enough to end our marriage. Although I sensed something akin to divine consciousness imposing its will on all of our lives, and the future still seemed filled with promise, I preferred to take the news personally. And, as time went on, even the crisis in confidence I indulged for longer than was useful turned out to be a gift from on high.

In the days leading up to our amicable divorce, mostly in service of a bruised ego, I came up with a romp-in-the-sack ode to some yet-to-be-named knockout, shamelessly titled “Lovin’ All Night.” Thinking I’d likely stolen the melody from Chuck Berry, I forged ahead, scribbling on the back of an envelope a lust-riddled homage to bedroom hijinks. I knew the song wasn’t in a league with “Lay Down Sally” or “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” but the time had come to assemble another album. And who better than my ex-wife’s new boyfriend to help transform a mediocre tune into a decent record? I wasn’t surprised when the record company brass chose the song for release as a single, but I was dumbfounded when they approved a six-figure budget for the promotional video.

Having been hired to produce grand results with the corporate bigwigs’ money, my friend Joanne Gardner sat at the kitchen table outlining a concept in which she and I would fly out to Los Angeles and work with an eccentric director whose visual flair we both admired. “Great idea,” I said truthfully. “But we can’t do that. We have to shoot this video in Nashville. And you have to direct it. Think how much fun it will be to tell the folks at Sony we’re cutting the budget in half. They won’t know what to do with themselves. Besides, there’s someone I’m going to meet who will be important to me.”

The principal actor I’d picked out of a stack of black-and-white eight-by-tens was three hours late for the first day of filming. Ever the professional problem solver, Joanne located a professional model and actor who could be on set in twenty minutes. The cameras had been in place for close to two hours when Joanne introduced me to the video’s new love interest. Suddenly, the idea that she planned to film me kissing this stunningly beautiful woman on the lips made me painfully shy.

Me: “I’ve never kissed anybody in front of a camera. Have you?”

She: “Yes.”

Me: “Is it okay if I try to make it look real?”

She: “Yes.”

One kiss and I was staggering drunk on her for the next year and a half. That is, until a blinding fear of commitment crept into my psyche.

I’d decided to end the relationship when a parcel arrived in the mail from the legendary lyricist Will Jennings. A package from the man so revered in songwriting circles for his work with blockbuster film composers and rock stars was a welcome sight. In contrast to the dynamic that made him one of Hollywood’s leading wordsmiths, our collaborative efforts involved me conjuring lyrics to fit his melodies. Scrawled across the top of the cassette he’d sent were the words remember me. Inside was arguably the most compelling piece of music he’d ever composed.

In the beginning, I didn’t see the emerging song for what it was: a painful denial of a kind woman’s love. I more or less pictured “Please Remember Me” as a relatively considerate way to break up with my fabulous girlfriend. It wasn’t until I finally got around to playing the song for her that the truth hit home: I was a coward.

“That’s a good song,” she said quietly when I finished. “But I don’t buy it. You and I belong together. Go on and do whatever it is you think you’re supposed to do. You’re a smart man. You’ll figure it out.”

Of course, I went on and did what I thought I was supposed to do—mope around the house for a couple weeks, book a studio and some musicians, and try to make a demo of the very song that had made me so damned miserable. And then, midway through the session, she walked through the door looking like the first day of the rest of my life. The musicians stopped playing instantly. The bass player, a close friend who was aware of the situation, turned to me and mouthed, “Last chance, pal.” Someone called out “smoke break” and we were left alone in the studio.

She: “For my peace of mind, I needed to say goodbye in person.”

Me: “You look great.”

She: “I don’t feel great.”

Me: “How about I cook dinner for you tomorrow night?”

She: “Are you sure that’s what you want?”

Me: “I’ve never been so sure of anything in my life.”

The next day I called the saxophone player, Jim Horn, whose culinary skills are nearly as famous among musicians as his flute solo on “California Dreamin’.” His recipe for baked salmon with orange wedges and red onions sealed the deal forever.

(To date, Claudia and I have been together for thirty-plus years. Rosanne Cash and John Leventhal, even longer. “Lovin’ All Night” made the top ten on the country music charts. Tim McGraw’s version of “Please Remember Me” was the number-one country song in the nation for five consecutive weeks. It also reached the top ten on the pop music hit parade.)