Olivia Newton-John’s Catalog of Emotion

And the quiet power of her voice

By Annie Zaleski

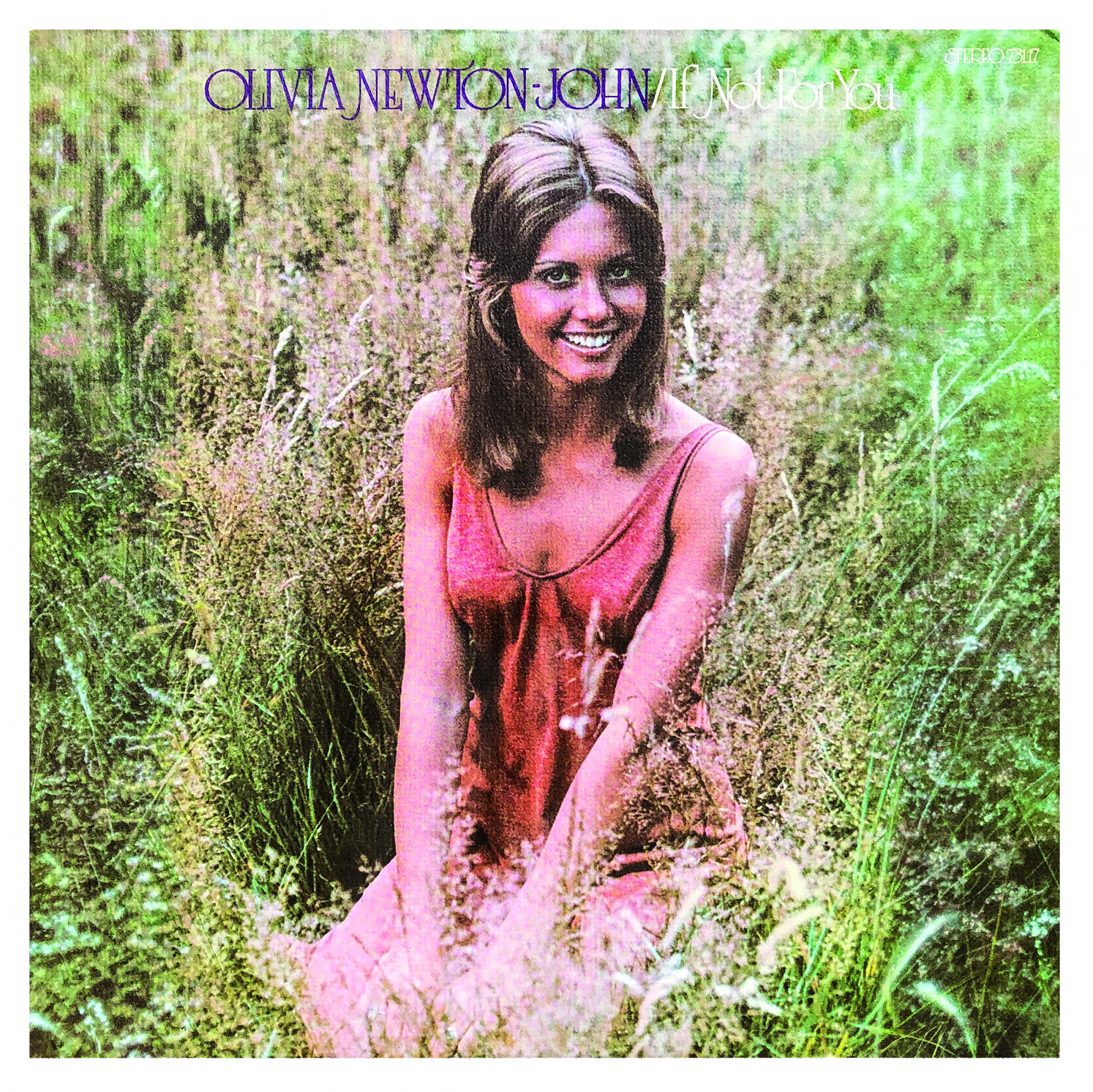

If Not for You released in 1971 by Festival Records. Photo by Carter/Reddy

Olivia Newton-John recorded just three takes of her first U.S. number-one pop hit, “I Honestly Love You.” As detailed in her 2018 autobiography, Don’t Stop Believin’, she used the first try for the final version. “I’m not a power singer but more of an interpretive one,” Newton-John wrote. That certainly became obvious when you compared her to contemporaries like Barbra Streisand or Anne Murray, both of whom belted out hits like they were on a grand stage; instead of nuance, they preferred more direct deliveries. But Newton-John’s self-assessment undersells the fact that her interpretive gifts possess immense power; much like Karen Carpenter—who was also a vocalist who exuded quiet strength as she sang—Newton-John dug deep into and empathized with the emotional core of a song.

In practice, that meant Newton-John didn’t hold back during good or bad times, and she wasn’t coy about her feelings. This gave her music a rich emotional range. For anyone going through major life changes, she was an upbeat presence, a friend extending a hand to the bereft via songs that were wistful yet reassuring. Yet Newton-John didn’t shy away from hard truths: When she sang about romantic disappointment, she didn’t sugarcoat the heartbreak, acknowledging in a weary but knowing tone that life could be bittersweet. But when life was going well, Newton-John’s innate, sunny optimism shifted to the forefront and exploded into effervescence.

Such transparency and vulnerability were enormously appealing, and led to commercial success on both the country and pop charts. Newton-John’s mellifluous voice also made her work distinctive. She learned from the best, as she’d grown up listening to expressive soul and r&b stars such as Dionne Warwick, Ray Charles, and Nina Simone on the radio. Folk music taught her how to harmonize. Years of performing live in clubs and on army bases with her friend Pat Carroll, under the moniker Pat & Olivia, made Newton-John comfortable and confident putting her stamp on any kind of material.

Once she embarked on a solo career and made a push for mainstream success, Newton-John became known as a nuanced vocalist who slid comfortably between adult contemporary, Top Forty, and country. Her voice was filled with gratitude on her cover of the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows,” but she balanced complex feelings—hesitancy, loneliness, regret—on “I Honestly Love You.” It’s no wonder she eventually succeeded in acting. As a vocalist, she fully inhabited the characters in her songs: the spurned lover overcoming wounded pride (“You Ain’t Got the Right”), an ambitious girl leaving home and striking out on her own (“Country Girl”), someone resigned to change and looking for a new place to belong (“Home Ain’t Home Anymore”).

This emotional depth came in large part from long-time, trusted collaborator John Farrar’s gifted production and arrangements. (On early albums, co-production also came from Bruce Welch, a member of Australian band The Shadows.) The strings on “Country Girl” possessed cinematic drama, giving her tale of leaving home the grandeur of a Hollywood movie. A wriggling pedal steel on the Bob Morrison composition “The River’s Too Wide” or solemn gospel choir on “Take Me Home Country Roads” gave her songs measured contours. Even if her music was fussed-over, it wasn’t overly fussy.

Despite this lyrical focus on interior lives, Newton-John’s career was often defined by larger-than-life moments. As Grease’s girl-next-door-turns-rebel Sandy, she created the blueprint for countless teen movie leads, dazzling as an open-hearted romantic with enviable poise. In the wake of Grease’s success, Newton-John starred in the disco-era dud Xanadu—itself an over-the-top display of retro pizzazz—but rebounded into pop superstardom. The sinewy 1980 pop number one “Magic” hinted at the kind of pleasures detailed more explicitly in her synth-rock wink “Physical.” The latter song spent an impressive ten weeks atop the U.S. pop charts in late 1981 and into 1982. These movies and songs propelled Newton-John to dizzying levels of fame in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But Newton-John’s wholesome glam is forever fascinating: Her fizzy 1983 hit “Twist of Fate” even received a bump after being included in the season two finale of Netflix’s Stranger Things.

Newton-John’s ubiquity no doubt had much to do with her role in Grease. Yet, while she was embraced in Hollywood, Nashville was another story. Born in England but reared in Australia, Newton-John didn’t have the history with Music City or the relationships that most country artists had.

The dynamics within her vocal performances were often overlooked. Upon the release of her 1971 debut album, If Not For You, critics quickly came to a consensus about Newton-John’s vocal timbre and delivery, frequently using words like “soft” and describing her approach as “wispy breathless, unoffensive.…Janis Joplin’s stylistic antithesis” (Pensacola News Journal). Once she started landing country hits and winning awards, Newton-John was forced to defend her sound and music.

In a 1974 interview with the Louisville Courier-Journal, she had an even-keeled response when questioned about not having a country twang. “I don’t put on an American accent or a Nashville accent. When people sing, they pronounce words in a different way.” Her disinterest in conforming to tradition or one dominant style ended up being a strength—and it proved enormously influential on country music for decades to come.

After Newton-John’s death in August 2022, I couldn’t help but think that the glossy moments and characters unfairly overshadowed her country stardom. Before she was perky, leather-clad Sandy or a spandex-wearing video star, she was a genteel and meticulous steward of folk-pop. Unlike much easy listening from the Seventies, which faded into vanilla sonic wallpaper, her albums sounded warm, intimate, and compelling. Being a Nashville outsider served Newton-John well, as it gave her space to define her voice on her own terms. She recorded versions of songs by John Denver, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, and Bread, as well as originals penned by close collaborators like John Farrar and John Rostill. She made unexpected choices, too, covering the Hollies’ “The Air That I Breathe” and the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.” Newton-John didn’t feel beholden to musical tradition; she saw possibilities, not limitations, within country music. During the first era of her career, this steered her toward material with more depth than people might realize.

“IF NOT FOR YOU”

On paper, the romantic lyrics of Bob Dylan’s 1970 ramshackle country-rock tune “If Not For You” are about as vulnerable as Dylan ever got: “Without your love I’d be nowhere at all / I’d be lost if not for you.” He knows the song is meant to make up for an indiscretion; this charm offensive even rhymes at points (“sad and blue” and “if not for you”). A whiff of apology seeps through Dylan’s gruff voice. George Harrison’s folk-driven approach to the song, as heard on his 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass, strips away Dylan’s bashful subtext. With a smoky voice, Harrison affixes his heart to his sleeve, declaring fidelity and fealty. The doubt coursing through the original version falls away. If Dylan is trying to convince his beloved to care once more, Harrison knows his relationship is secure, and expresses gratitude and affection for his significant other.

A year later, Newton-John covered the song on her debut. It spent three weeks at number one on Billboard’s easy listening chart and was a Top Forty pop hit. Through a modern lens, the country and Americana flourishes are obvious; her take is more easy-going, less brash.

Newton-John wasn’t overly enamored with the song, at least at first. “I didn’t think it was my type of song at all, and I had a little bit of trouble being convincing in putting it over,” she is quoted as saying in the 2008 biography, Olivia. “But everyone else was so enthusiastic that I came around to liking it eventually.” It wasn’t a question of taste, as Newton-John grew up harmonizing with Dylan’s music and channeled his nuanced vocal delivery.

Listen closely, and Newton-John’s interpretation of “If Not For You” might not be a straightforward love song. She picks up on the desperation weaving through Dylan’s version; in a later verse, her voice soars upward sharply on the lyric, “My sky would fall,” rendering the line in a grief-stricken vibrato. Elsewhere, her vocal delivery trembles with nostalgia and ripples with melancholy; it’s easy to interpret the song like she’s imagining this perfection, rather than living it. Newton-John is tending to the happy memory like one would a flourishing garden, nurturing it so it sustains during darker times.

“LET ME BE THERE”

Newton-John came into her own as a country artist in 1974, which is when “Let Me Be There” became her first top ten U.S. country and pop hit. In March, the song also earned her a Grammy Award for Best Female Country Vocal Performance. This win foreshadowed bigger honors. Later in the year, she won Promising Female Vocalist of the Year from the Academy of Country Music Awards (ACM) and Female Vocalist of the Year from the Country Music Association (CMA). In a taped acceptance speech for the latter honor, Newton-John went out of her way to praise Music City. “It’s a long way from London to Nashville, but I’d like to take this opportunity to say a big hello to all the friends I made on my last visit there,” she said. “And I hope to see you all soon when I fulfill an ambition of mine to record an album in your hometown.”

The olive branch didn’t help. Despite this benign greeting, Newton-John’s win angered Nashville traditionalists. On November 12, 1974, a group of fifty country A-listers gathered at George Jones and Tammy Wynette’s house. The occasion was to convene a new organization called Association of Country Entertainers (ACE), whose goal was preserving the status quo—capital-A, authentic country music.

The language used by ACE participants was suspicious, blaming what seemed like a musical strawman for perceived usurping. “Our gripe, if we have one, is that these people want to come in and take our music away,” musician Bill Anderson told the Associated Press, adding that he meant artists “not willing to stand up and say, ‘I am a country artist.’” Billy Walker was more explicit, blaming outsiders who infiltrated Nashville. “These people came in and prostituted our business and watered down our music. This was done by big money on the East and West Coast.” At a press conference about the organization, Newton-John was singled out specifically for being considered a country interloper; namely that she was one of the artists refusing to label herself as a country artist.

Newton-John gamely told the Associated Press in 1974 that she didn’t “think it was too much planned that I’d become a country singer” and that her producer encouraged her to go in that direction. That didn’t necessarily help her cause, although in the end she had high-profile defenders in country music circles, like Dolly Parton and Loretta Lynn. (In a 2016 social media post, Newton-John praised Lynn for her 1970s support.)

Newton-John wasn’t hiding her influences and, more importantly, she didn’t back down or change her approach due to the exclusion or criticism, carving out her own way within the genre. Her 1973 LP Let Me Be There, which included songs from her previous albums, topped the Billboard country charts. Newton-John belted out versions of “Angel of the Morning” and “Me and Bobby McGee” with the confidence of a rock band leader; dipped into gospel for “Banks of the Ohio” and “Take Me Home Country Roads”; and turned in a gorgeous version of Gordon Lightfoot’s heartbreak anthem “If You Could Read My Mind” full of sighing vocals and weeping strings.

The LP’s title track was a turning point in her confidence. Written by John Rostill, the song is structured as a plea from one person to another. The narrator shows willingness to be a support system to a special someone (“Let me be there in your morning / Let me be there in your night”) and to fix whatever’s wrong. “Let Me Be There” increases in musical intensity, building on a foundation of wiry pedal steel and acoustic guitar by piling on darting strings and vocal layers.

British musician Mike Sammes contributed deep harmonies in the background that add weight to and echo certain lines (“Make it right,” “Oh, let me be there”). By the final verse, a dramatic key change lifts the song, turning it almost into a cathartic church hymn with Newton-John singing near the top of her soprano range. It’s clear she is all-in on the relationship; however, it’s unclear whether the other person is. “Let Me Be There” is a leap of faith, a prayer tossed out into the world from one believer to another.

“HOPELESSLY DEVOTED TO YOU”

For country artists looking to switch to pop music, a gradual evolution tends to be more successful. By jettisoning familiar sounds all at once, musicians run the risk of alienating existing audiences or sounding insincere. Shania Twain made this move masterfully in the Nineties, recording two versions of Come On Over to appeal to country and pop audiences and then assimilating both genres seamlessly on 2002’s Up!. In the following decade, Taylor Swift also followed this blueprint as she transitioned from country stardom to stadium pop, releasing different mixes of her 2012 single “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” on the equally eclectic Red. Like Newton-John, both received pushback, but were proven correct in their approach.

Newton-John helped develop this crossover-success playbook, although she had a distinct advantage because she was used to sliding between pop and country. But prior to the release of Grease in 1978, her country fortunes had faded. She hadn’t had a top ten country chart hit since she released her 1976 version of the Bee Gees’ “Come On Over” and began inching toward mainstream rock and pop sounds. Her first solo album post-Grease stardom, 1978’s Totally Hot, featured a twangy ballad, “Dancin’ ’Round and ’Round,” but the rest of the LP was fiery disco and rock.

John Farrar was by her side throughout. She navigated evolving trends so well because of Farrar’s production, which eschewed then-contemporary techniques that might have made the music sound dated, instead developing arrangements and material suited for Newton-John’s voice and style. And for Newton-John’s solo showcase in Grease, Farrar wrote and curated “Hopelessly Devoted to You,” a song that applied a Fifties pop sheen to her early country work. The single was a top twenty hit on the U.S. country charts, reached number three on the pop charts, and was also nominated for an Oscar.

“Hopelessly Devoted to You” suits a Hollywood film: Brassy and polished, it incorporates waltzing pedal steel, anguished strings, and an imperceptible groove driven by soft, clicking rhythms. Lyrically, there’s no room for ambiguity; “Hopelessly Devoted to You” is firmly wallowing in heartbreak. Newton-John sounds subdued on the first verse, almost as if she’d just had a good cry, as she softly sings, “I’m not the first to know / There’s just no getting over you.” Then her voice intensifies as she declares her distress: “I’m out of my head / Hopelessly devoted to you.” These extremes settle into sorrow over the rest of the song, and when she repeats her lament (“Now there’s nowhere to hide / Since you pushed my love aside”) the resignation stings. “Hopelessly Devoted to You” is a country weeper in the grand tradition of lonely teardrop songs masquerading as a manicured pop confection. It was a perfect way to close the book on the country chapter of her career.