Photograph courtesy True Groove Records

Future Roots

Tomás Doncker on his twenty-year collaboration with Yusef Komunyakaa

By Larry Kay

Musician Tomás Doncker and poet Yusef Komunyakaa met and began collaborating over twenty years ago. Keenly aware of the common bonds between the roots of country and blues—poverty, the church and gospel, and a telling of truths cloaked by folklore and tales that go back generations—Komunyakaa and Doncker tap into that commonality with reverence and respect. The result is something entirely new and genre-defying: Black Americana. It’s a re-imagining of American roots music that looks to the past and future simultaneously while touching on an array of twentieth-century influences from country to blues to soul.

Doncker details the process behind their unique collaboration and how the records they’ve made together touch on different aspects of the roots music canon:

“COUNTRY IS A FEELING”

When Yusef and I first started working together, he made it very clear where his musical interests lie. He’s one of the great collaborators, but he’ll never say something specific like, “We’re going to do a blues record”; he contributes overall thematic concepts and ideas that help define our starting point. He’s the lyricist and I’m the primary songwriter in this relationship, so the tone and vibe of the lyrics are paramount and the music must serve that. The music we’ve created over the course of our relationship can’t really be easily ascribed to any genre. It’s as much blues as it is country, as much psychedelic as it is folk; it’s a feeling that stems beyond tradition. Listen to Son House’s “Death Letter”—he’s country, no doubt. The sound of his guitar playing supports the pain in that lyric. We have no idea what his process was, but it’s a complete experience when you hear that song. The music and the lyric are one thing: an experience unto itself. Very early on in the course of our conversations, before we’d even made any music together, or even conceived of The Mercy Suite [their first collaborative album], Yusef said, “We need some new blues, blues that doesn’t rhyme with worn-out shoes.” I looked at him and thought, “I like this guy; this is how I think.”

Blues is a feeling in the same way country, at its core, is a feeling. It transcends traditional subject matter, it has to move beyond those old forms for the genre to grow and expand. We set out to create our own blues and arrived at a place we’ve alternately called Black Americana or Future Roots Music. We only came up with those monikers because people kept asking us what we were doing. Our music wasn’t easily defined; it didn’t fit into any traditional conventions. Americana, in my opinion, is a relatively new marketing term. Its obvious immediate attachment is to country music, but one could make a very valid argument that all three truly original American musics—jazz, blues, and country—are all Americana by virtue of their existence. We’re not talking about what’s very often identified as the country music that came out of Nashville after WWII—these are the real roots; country music whose bonds unite the backwoods of West Virginia with the Mississippi Delta, the Louisiana swamps and the Appalachians, which is regional and national at the same time via the same shared experiences.

“WILLIE DIXON, COLE PORTER, AND HANK WILLIAMS ARE BASICALLY THE SAME PEOPLE”

When we started using the term “Black Americana,” the most frequent response was, “Oh that’s so radical!” Really? Anything a black man does is American. Who built this nation? We came up with it as a blatant “fuck you” to anyone who had to have a genre-specific description of what we do. We also call it Future Roots Music, which is both an oxymoron and a metaphor. Where do you go, musically, when you want to create something new that still embraces aspects of the past? You look back with one eye and forward with the other. Yusef was saying he’s tired of hearing the same subject matter over and over, the same blues stories and tropes that have been told for the past fifty years. When we were working on our second album, Big Apple Blues, we spent a lot of time listening to, enjoying, and absorbing the work of the great Willie Dixon. His songs take you on a journey. We were reveling in the power and simplicity of the storytelling; you can see the characters.

Take a song like “Wang Dang Doodle.” You know who these people are; their situations transcend race and geography. These are songs about anyone’s home, community, and neighborhood. They’re universal stories and they celebrate the commonality in human beings and, more often than not, these stories are undermined by the need for genre-specificity in today’s world. We don’t subscribe to that, we just don’t. That’s part of the thing that’s clipping the wings of the music. You can take almost any Willie Dixon song and it would work equally well if it was sung by Hank Williams or the Carter Family; the truths in the lyrics are universal. In The Last Waltz, Levon Helm called Muddy Waters “the king of country music,” and that’s what it’s all about. Take one of those storytelling building blocks: poverty. The notion of poverty being just a rural thing is long gone. It’s an urban thing. It’s a lens through which life’s stresses are experienced. In the same way the landscape through which country and blues have expanded, Yusef and I have expanded our work. From these fundamental starting points in American music we’ve stretched into rock and roll, funk, soul, rhythm & blues, and even songs in the style of the Great American Songbook. We see them all through the same lens; we see them all as coming from that same Willie Dixon place. If you look at it, Willie Dixon, Cole Porter, and Hank Williams are basically the same people: their songs are all equally descriptive, just the genres they write in are different.

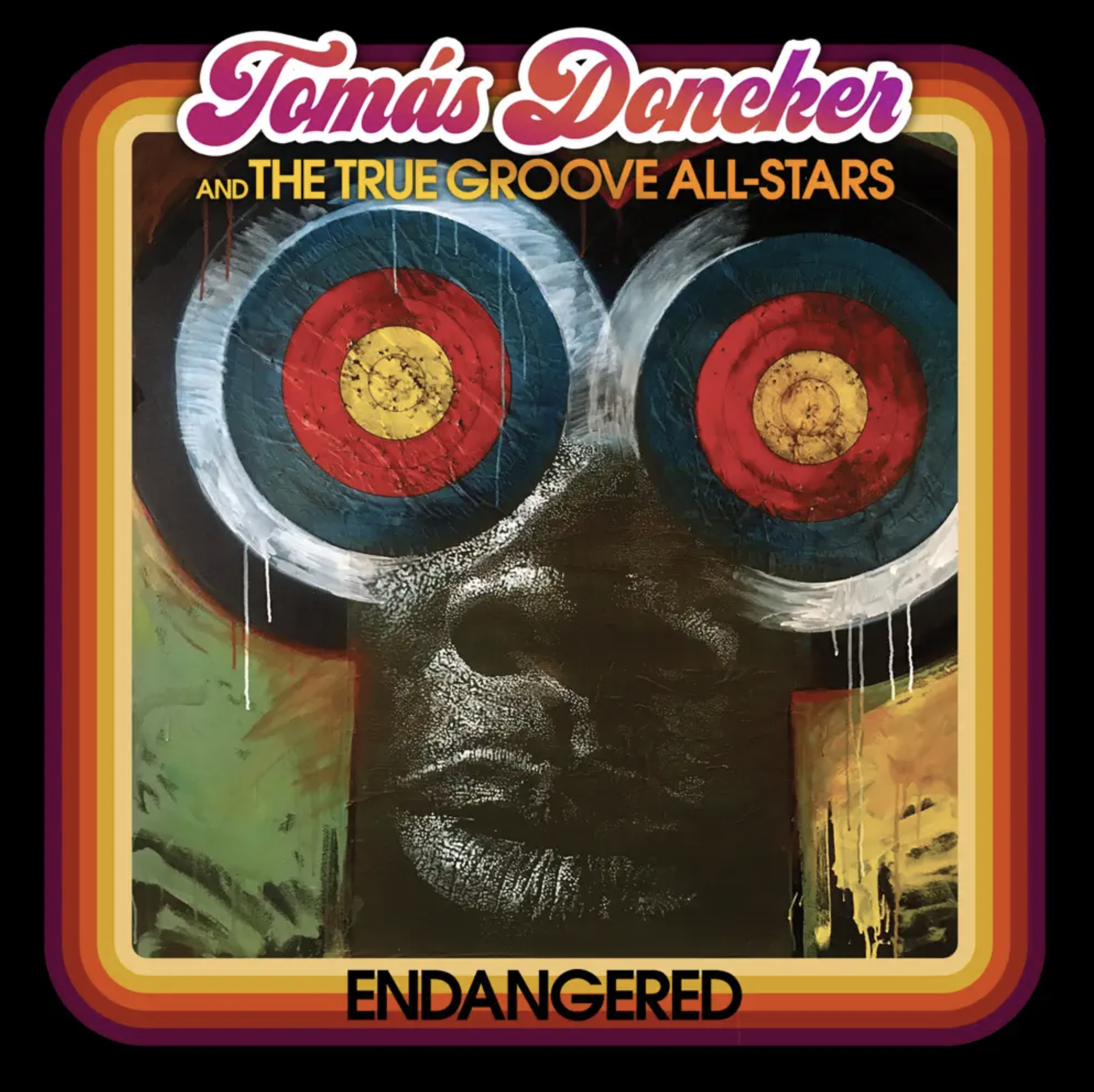

Endangered released in 2022 by True Groove Records. Courtesy True Groove Records

“ALL THE ROOTS GET TANGLED UP”

Yusef and I have also written songs that deal specifically with his experiences as a soldier in Vietnam. It has been my honor and privilege to lend my voice to the telling of these stories from his youth. I’ve never served in the armed forces, nor would I assume to fully understand that experience, but there have been many times I’ve felt the anxiety, anger, fear, and confusion that comes with walking in those shoes. From the moment we recorded “Whenever I Close My Eyes” [for The Mercy Suite], the journey of my life was forever changed. It was a very conscious choice during the creation of the song for us to tell a story that’s not so much about one man’s relationship with a woman, but to the ass-whupping one man can receive from the whole idea of being in love. Other songs from The Mercy Suite that tap into those universal truths are “Shook Down” and “Ride the Wind.” The determined, uplifting, gospel-country-blues stride of “Ride the Wind” was deliberately designed to celebrate the internal strength and resilience one finds through faith—any form of faith.

Big Apple Blues is connected in many ways to The Mercy Suite. The album had a decidedly electric, Chicago blues vibe, but at the same time it ventures into psychedelia and even the traditions of the Great American Songbook, so, again, all the roots get tangled up, but still make musical sense. And the same could be said about our third album, The Black Magnolia Project. If you really listen you’ll hear elements of a classic two-step interlaced with psychedelic alt-country and gospel blues.

“NEW CHAPTERS THAT READ LIKE OLD TEXTS”

Our new multimedia album, Endangered, picks up almost exactly where The Black Magnolia Project left off, four years ago. We expanded our collaborative sphere by bringing in visual artist Floyd Tunson and using his work for inspiration. It’s the most futuristic of our records, constructed as a travelogue through contemporary black music styles. The ever-present influence of the blues looms large, but it touches on everything from hip-hop to afrobeat to hill country blues to southern-fried soul to Negro spirituals. It’s the distilling point of The Mercy Suite and Big Apple Blues. It was a collaborative, face-to-face project, where the artists and their respective disciplines converged. We mine the common ground which all of this music came from a hundred years ago (or more!) and try to write new chapters that read like old texts.