Lady Vols Country

By Jessica Wilkerson

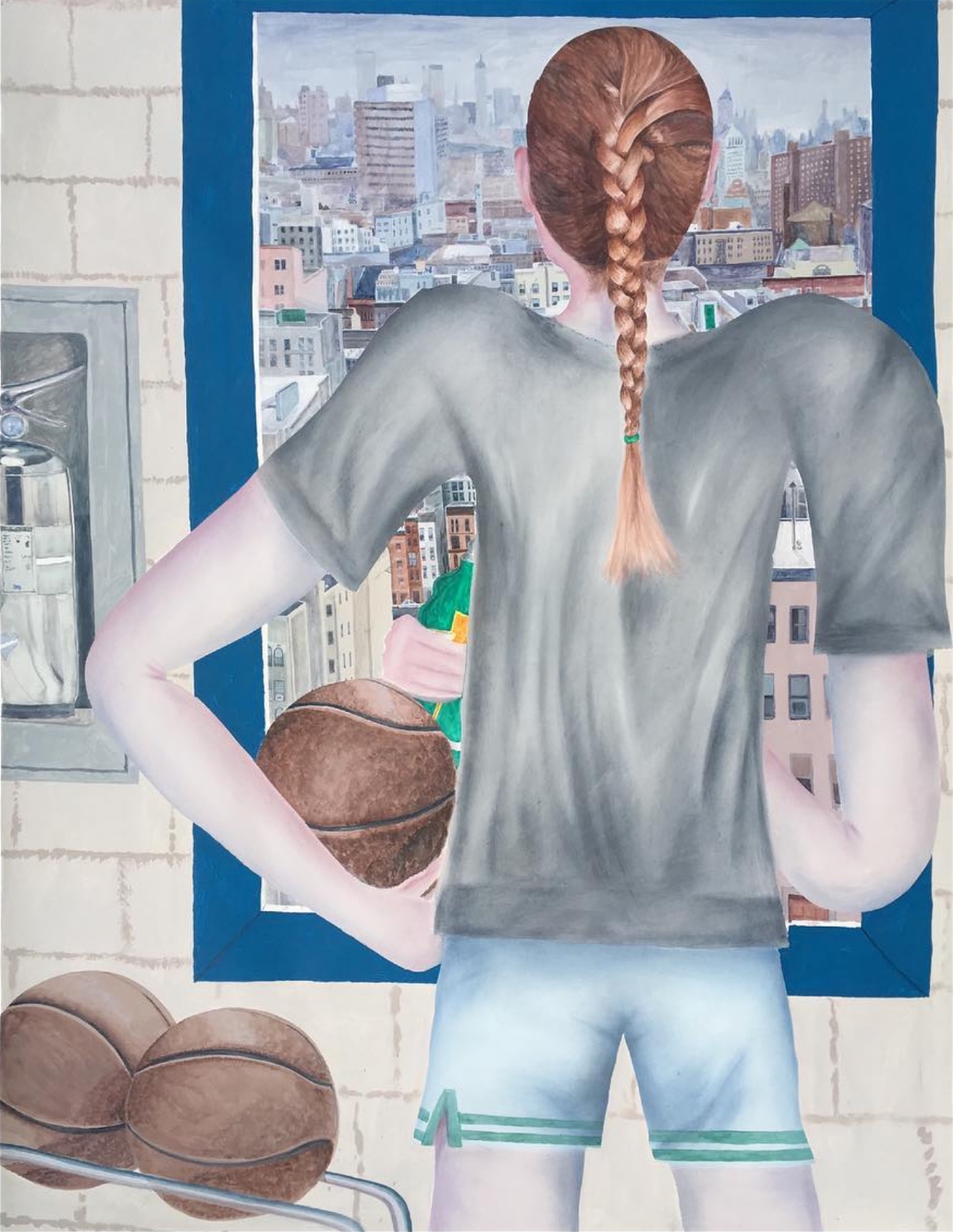

Public Courts, 2019, watercolor on paper by Charlie Roberts. Courtesy the artist and Woaw Gallery

I spent my childhood in the country about fifteen miles north of Knoxville, Tennessee. The center of our little community was Harbison Crossroads, on one corner a gas station and the other the IGA, where one could purchase pickled eggs and handmade clothes for Barbie dolls. Once my friends and I could drive, we went to the closest Walmart and browsed magazines—Cosmopolitan, Allure, Teen. The more sophisticated knew where to find markets off two-lane roads where merchants sold cigarettes and beer to teens. The Internet didn’t arrive until I was about to graduate high school, and when it finally did, it was too slow, and I was too impatient.

Our dads built, fixed, and sold stuff. Our mothers worked as secretaries, nurses, and dental assistants, in food service, and at department stores. Everybody went to church, mostly Methodist and Southern Baptist, an occasional Presbyterian. The pastors—white men ministering to white congregations—read scripture and told jokes with moral lessons. To get to our house, you turned off the main two-lane road across from one Southern Baptist church and turned right just before you reached another. For a month of every year, the one on the main road decorated its church lawn with dozens of tiny white crosses that represented aborted fetuses. My parents were not particularly devout, but they let us go to youth groups with friends and cousins, virtually the only place to socialize outside of school. During my teen years, the focus of youth pastors was on abstinence and the necessity of saving boys from the sin of sexual desire. Homosexuality and abortion were the two worst sins one could commit. I remember the first time I heard this, during a Bible school I attended with a friend. The youth pastor, red-faced and sweaty, screamed at us, a group of distracted kids sitting quietly on the polished wooden pews and eager to return outside, beyond the gaze of the adults who perceived our bodies as threats.

These were the years of third-wave feminism. But in the country north of Knoxville, Riot Grrrl, zines, and coffeeshops did not exist. Instead, there was full-on cultural backlash that never appeared as backlash so much as a continuation of how things had always been—a man’s world, and we were living in it. Adults around us communicated that feminism of whatever wave was dangerous, was a joke, was ridiculous, with one glaring exception that could never be identified as such: the success of Pat Summitt as head coach of the University of Tennessee’s Lady Volunteers basketball team. For nearly one hundred years, women had been assumed too weak and dumb to play the sport competitively, but the Lady Vols, led by Pat, helped to change that.

By the Nineties, softball and basketball had become rites of passage for girls in our community. At the nearby ballpark or in the old high school gym, my younger sister and cousins—girls with tanned arms, knobby knees, and French-braided hair—practiced skills that would prepare them for high school teams. Some even attended sports camps in Knoxville, begun by Pat in 1977 amid ongoing challenges to the legitimacy of women’s athletics. Many would go on to win regional and state championships. There was nothing special or startling about these scenes of girls’ athletic excellence. They were part of everyday life, the most visible evidence of a changing society that coexisted with messages that constrained girls’ existence.

Sports are not just about sports. They encompass a battleground for determining how gender manifests in the world, how women and girls can use their bodies, and who can access self-determination. For many of us, even those, like me, whose imagined future arena was not in sports, Pat and the teams she led sent low-wave frequencies of possibilities for a different kind of life. I received these messages as a girl in East Tennessee. Feminism was not a word spoken much around me, but I saw an important representation of feminism as a thing a person did (rather than what they were) in Pat’s career.

I attended my first Lady Vols basketball game in the Nineties, when I was a teenager and when the team was on its historic run, winning three national championships in three years. Pat wore a power suit and her hair short, and she was legendary for her stare that contained multitudes. She exuded a version of womanhood I had never seen. On my way to the game, an older male family member had told me to be careful not to get kidnapped, insinuating that lesbians lurked in bathrooms at Lady Vols games. This same family member would just as quickly exclaim that Pat Summitt was the greatest coach of all time. So good, in fact, that the NBA tried to hire her as a coach. So excellent that she was qualified to give men advice.

This was but one example of the paradoxes we lived with in Lady Vols Country—a deep pride in the woman who dominated college basketball, men’s and women’s, alongside anxiety about the meaning of a woman-controlled space. Pat had made a career of navigating these contradictions, but it all started with the simple act of her parents giving their daughter permission to live the life she craved.

When Pat Head was a girl, her family called her Trisha (pronounced TREE-sha), and her friends called her “Bone” because she was long and lanky. Growing up in the 1960s, she was a natural athlete and described herself as a tomboy. She learned to play basketball with her brothers in the hayloft of the barn, where her father had rigged up a backboard and hoop.

Pat burned to play basketball. When she was in third grade, the school principal invited her to practice with the eighth-grade girls’ team. Through her middle grades, she played a six-on-six half-court game, also known as the “girls’ rules.” Three players from each team stayed on either side, forbidden from playing full court because adults feared it would exhaust or injure them. That meant that defensive players only ever guarded offensive players on the other team and never shot the ball, and offensive players never learned to play defense. Meanwhile, boys played five-on-five, full-court basketball.

In her final memoir Sum It Up, Pat described how, one night at dinner, she complained that the high school in her district lacked her sport. According to Pat’s recollection, it was banned after a player had gotten injured and died, thus confirming everyone’s fears that team sports were too dangerous for girls. Pat’s father replied, “Well. We’ll just move.” As Pat remembered, “It was an extraordinary statement.” Extraordinary, I imagine, because it was permission to use her body and mind the way she desired. The Head family crossed over the county line, where Richard owned a grocery store. They bought a dilapidated, drafty farmhouse in Henrietta, Tennessee, a small town with a main drag. As a freshman, Pat started as the forward for the Cheatham County Central High School team. Her older brothers, all accomplished athletes, had received athletic scholarships to attend college. Since that was not an option for girls, her parents, who Pat described as cash poor, once again strategized to find a way for Pat to go to college and play ball, scraping together the money to pay tuition at the University of Tennessee at Martin.

In 1970, Pat arrived at UT Martin with one suitcase, handmade clothes, and not a clue about how to wear makeup or fix her hair in the popular style of the day—teased in place with hairspray. She was a country mouse. The other women, who she described as wealthy Memphis socialites, spoke elegantly, no “ain’ts” or “reckons” in their vocabulary. The girl who had spent her childhood baling hay, drag racing down dirt roads, and barrel racing horses soon learned how to become a lady. She found a mentor in another student, who recruited her into the Chi Omega sorority—a tried and true training ground in white Southern femininity. Pat began to wear fashionable clothes and makeup and went on dates. Her sorority sisters coached her on cleaning up her syntax and toning down her Tennessee hills accent. She began to change from the tomboy of her childhood into a feminine woman.

This transition was important for a young white woman attempting to play mainstream college sports. Fears abounded that white, sporty women risked becoming masculine if they were physically active. By learning to perform a certain kind of womanhood, Pat created for herself a shield. And that she did is confirmed by how at least one reporter described Pat after a game, to her delight: “Pretty Pat Head.”

Even as she learned how to fit better into middle-class society, she felt most herself on the basketball court. The UT Martin women’s team was still playing half-court basketball when Pat arrived in 1970, but that soon changed. The year 1971 was a watershed moment in women’s college sports, with the formation of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (the women’s version of the NCAA) and the adoption of full-court basketball in women’s collegiate athletic programs—followed by the 1972 passage of Title IX of the Equal Opportunity in Education Act and announcement that women’s basketball would be represented at the 1976 Olympics.

On the court, Pat became UT Martin’s all-time leading scorer, helping her team win a state and regional championship. Off the court, she studied physical education and dreamed of joining the U.S. national team and becoming an Olympian. She got one step closer to that goal when she was invited to participate in the World University Games in the summer of 1973. In a whirlwind tournament in Moscow, Pat encountered the best players in the world and found her appetite for winning on an international stage. She came home with a broken jaw (“elbow to the face”), a silver medal, and newfound confidence: “It occurred to me that the winner’s podium was a pretty good place from which to conduct a women’s movement.”

Women’s sports draw attention to how girls and women move through the world. And while many girls played sports as I was coming of age—the years that people started to talk about the “Title IX generation”—contradictions abounded.

The first time I realized that girls could get pregnant, I was in sixth grade. The girl was older than me, maybe in eighth grade. I heard about her before I saw her, and then there she was in the bathroom. Tall and slender, the slightest of bulges under her oversized, bright yellow sweatshirt, she styled her bangs like waterfalls sweeping across her forehead. The second time, I was a freshman in high school. This time the girl was on the cusp of womanhood, or maybe already there by the fact of pregnancy. She wore a lipstick-red slip dress at the homecoming dance. She looked otherworldly, a cross between Courtney Love and high school cheerleader, and somehow carefree despite the thing pushing out her belly, smooth and taut.

And then pregnancy reached my friend group. She was fifteen and high achieving, earnest, with a round face and flushed cheeks. Our friends played like adult women and threw her a baby shower. She waited until we were all piled into a car, safely out of earshot of adults, to warn us about how easy it was to get pregnant. She filled in the blanks of our abstinence-only educations. She also became another number in the stats that we heard about our high school’s high rate of “teen pregnancy.” When “teen” modifies “pregnancy,” it turns it into something reckless—a stigma and a shame. My first year of college, I took myself to the local health department and endured the judgment of the middle-aged nurse. I left with a small paper bag filled to the brim with packs of birth control pills.

I’ve often wondered how Pat navigated reproductive politics as the coach of a women’s basketball team, all of those eighteen- to twenty-two-year-old women under her watch. But it’s not something she wrote about extensively except to say that she gave her players information (a “sex talk”) so that they could make the best choices for themselves. She also shied away from discussing sexuality, even as gay baiting plagued women’s basketball, and as several of her star players came out in later years.

Throughout her career, Pat carefully avoided associations with “capital-F feminism,” as she called it. She did not identify with activists who had marched in the streets, joined women’s rights organizations, or called for revolution. She accepted as truth the prevailing caricatures of second-wave feminism: man-hating, too brash, and too Northern. Yet she obsessed about how to topple barriers to women’s full inclusion in athletic activities—one might even say women’s ability to fully live in their own bodies.

Even as she later distanced herself from feminist movements, feminist policy and social change formed the very backdrop to her life. As a young woman, she sang along to Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman,” the feminist anthem released in 1972. She cheered on tennis star Billie Jean King during the televised “Battle of the Sexes,” in which King beat former tennis champion and attention-seeking male chauvinist Bobby Riggs. In 1974, at twenty-two years old, Pat started coaching at the University of Tennessee and helped to institute the changes brought about by Title IX. In 1976, she played in the Olympics and served as the USA team co-captain. That same year, she testified on behalf of a Tennessee girl who sought access to full-court basketball. She publicly called for an end to sexism in youth athletics, and she used her platform to threaten Tennessee’s girls’ sports association that she would stop recruiting in the state until they allowed girls to play full-court basketball (they soon caved). Over the next decade, she devoted her career to building an elite women’s basketball program. But she was also adamant that her cause was about more than access to a sport. Basketball, she wrote, is “about life skills, and life stories, it’s about trading in old, narrow definitions of femininity for a more complete one. It’s about exploring all of the possibilities in yourself.”

By the 1990s, Pat walked a line: She supported women’s access to sports, but she also publicly embraced family values politics, separating herself from feminist movements. She spent the entirety of her career in the thick Bible Belt of East Tennessee, navigating white evangelical politics and preaching personal responsibility. But the bodies on the court suggested something else entirely; they suggested choices, access to birth control and abortion, and knowledge about women’s bodies.

During the first meeting of my first women’s history seminar, the professor welcomed and congratulated us before acknowledging all the women whose dreams had died on the shoals of unwanted pregnancy.

My grandmother loved the Lady Vols and rarely missed a game, watching on TV or listening to the dry-witted, unforgiving announcer on the radio. After college, I had moved home and made a ritual of going to her house to watch the game. I made Folgers coffee, poured it into mugs (hers steaming black and mine cut with milk), and brought hers to her where she sat in a forest green recliner. I stretched out on the floor in front of the TV, my partner often joining us. This was 2007 and 2008. We didn’t know it, but these were the final glory years of the Lady Vols under Pat Summitt’s leadership, her final national championships. These were also the last two years of my grandmother’s life.

In the same spot where I had spent many an evening perched in front of the TV, my grandmother would soon be lying in a hospital bed, dying, a constant vigil of caregivers, visitors, and hospice nurses surrounding her. On one of our last evenings together, I sat beside her to say goodbye before I moved to a neighboring state for graduate school. She knew that it was potentially a final conversation. She took my hand and asked gently if my partner and I planned to have children. I did not expect the question. I also did not believe she was dying, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

A few years before, her body had begun a slow paralysis, first in her thumb, and then her hand and arm, her body wilting like a cut flower. She fell more frequently. And over time, her eyes stopped tracking like they should. Unable to read voraciously as she always had, she slid into a deep depression. The doctors had few answers other than noting that, intellectually, she was as sharp as ever. This was no solace to her. She feared being trapped in her own limp body, a formerly vigorous body. Her life was a sum of verbs: She milked cows, gardened, canned, sewed, weeded, walked, and supported four children, a household, and a husband who died too young. In the months before she died, she disclosed how she had always wanted to go to college, but that nobody could pay for it. I heard whispers of how she had often been an unhappy mother. Only at the end of her life, it seems, did she get to make a decision about her body, one granted too few people. After numerous harrowing visits to the ER and several long hospital stays, she had finally gotten her wish: to stay home during the next medical crisis, and to begin the process of dying on her own terms.

When she asked me the question about children, I stumbled over my words. This was not a prompt that people asked in the part of the country where I’m from. Children are assumed, especially of people young and married. Women get pregnant; women raise children.

I told my grandmother in halting words that I didn’t know if that—children, motherhood, sacrifice—was what I wanted. She squeezed my hand and whispered hoarsely, “You know you don’t have to.” In that moment, my grandmother broke an enforced silence around women’s bodies and the choices we can or cannot make and the implications of those choices for our lives. The next morning, I left for school, a choice she never had the chance to make. I left with the question and its underlying assumption that mothering was the only way to be a woman. Unlike her, I could live another way. I left with the imprint of her hand in mine, her words in my ears, saying out loud what I did not know I needed to hear. My grandmother, perhaps more than any other person, wished for me to set out to do what I wished with my own life, body, and mind.

I have analyzed the historical significance of Pat Summitt’s career since I became a scholar of women’s history. I know now, in ways that I didn’t perceive as a kid, that her politics were often conservative despite the paths she forged for women in sports. By the Nineties she had adopted a politics of individual achievement, espousing what she called “The Definite Dozen,” an unfortunately corny name for a set of rules for success. If only one worked hard enough and lived with discipline, they could achieve their wildest dreams, Pat promised. She downplayed the resilient churn of sexism and racism in American society and embraced individual success. The paradox, however, is that she built her own career on hard-won feminist policies, on women-led social movements, and on majority Black teams, whose women would continue to face society’s highest hurdles after graduation.

I wasn’t cognizant of Pat’s strand of individualist politics when I watched games, however. Instead, I saw a woman who was intent on winning, who was fearless and brash in her directives. I saw women in huddles, working together, the best at what they did, and ready to disprove every man who mocked women as incapable.

Pat embraced the basic yet revolutionary idea that women should be able to pursue the life that they desire, something that, historically, women have not been able to do. Pat Summitt had lived through two worlds: the one where society told women you can’t, and the one, fragile as it is amid growing attacks on reproductive justice and transgender rights, where it’s more possible for women to choose their fate.

I recently read Pat’s final memoir, Sum It Up—written after she was diagnosed with early-onset dementia, Alzheimer’s type, at a tragically young age. It’s an honest book that cuts through the public tightrope performance that she had walked as a high-profile coach in college sports. She writes candidly about her own struggles—being wracked with grief after multiple miscarriages; the stress of a failed marriage; the arthritis that plagued her joints and caused her much suffering; the slipping memory and gut-wrenching diagnosis. Amid all of that, she found joy and inspiration in working with athletes, supporting them and advising them in their own private struggles.

In one passage, Pat describes how she spiraled into darkness after receiving the diagnosis. In the ensuing months, a doctor advised her to retire immediately and remove herself from the limelight before she embarrassed herself and threatened her legacy. She balked. She went public with her diagnosis, with a mission to raise awareness and challenge the stigma associated with disability related to Alzheimer’s. She created a foundation to raise money for research. She remained as head coach for one final season, backed by a supportive coaching staff and players, and led the Lady Vols to one more SEC tournament championship. I see how she conducted herself in her last years as her final feminist act: Told to step aside when she was no longer at her shiny best—when her public presence would remind us all that at some point our bodies and minds fail us—she chose instead to put on display the power of women determining their destinies.