Guest Editor's Letter: A Deep Wanting To Know

By Tayler Montague

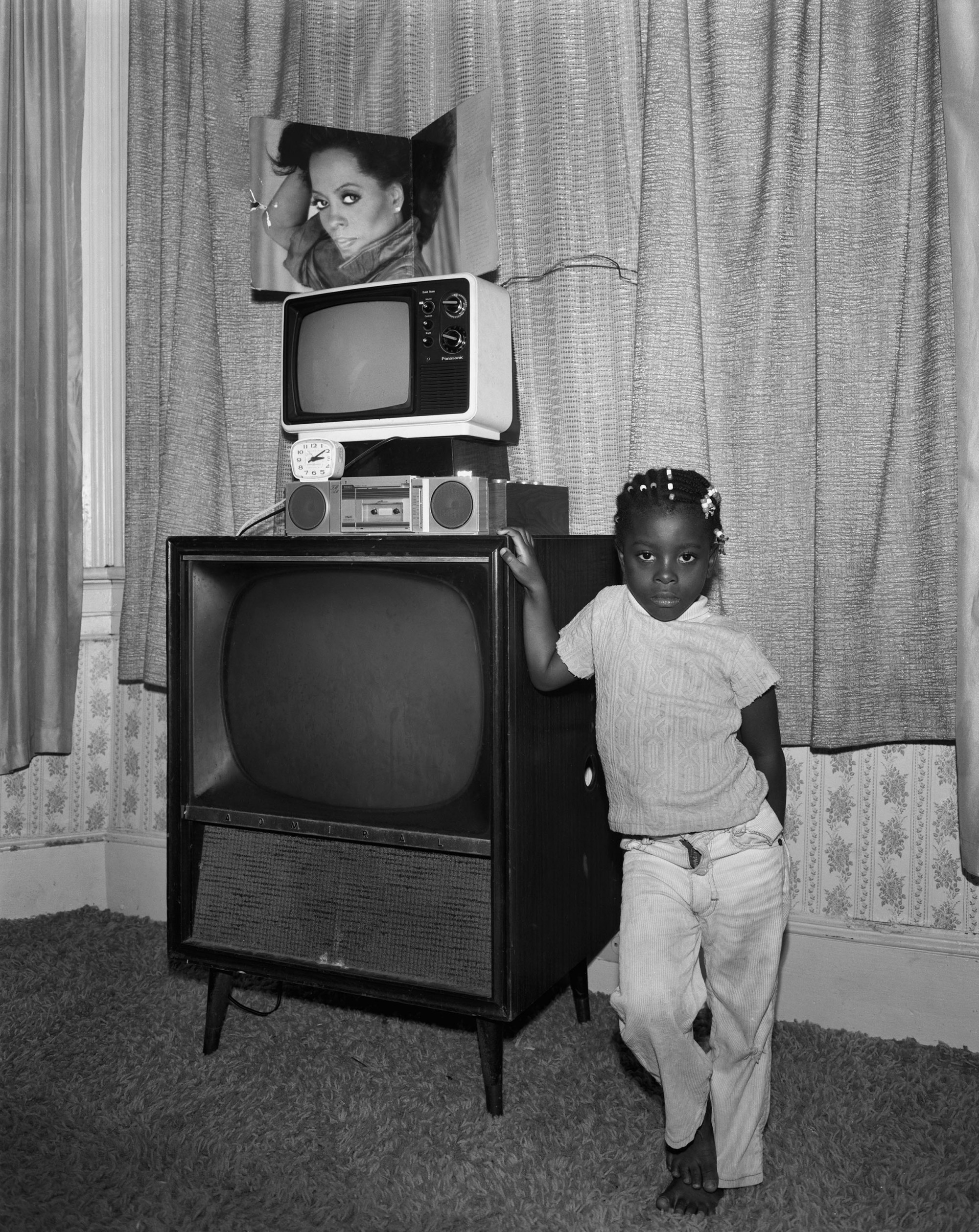

Charleston, South Carolina (1984), a photograph by Baldwin Lee. The third edition of his monograph, Baldwin Lee, was released in August by Hunters Point Press. © The artist. Courtesy the artist and Hunters Point Press

It felt like, cooling water

Just like, cooling water

Cooling water from Grandma’s well.

—The Williams Brothers

By the time we were performing our own rendition of the song, my cousins and I would drop out the “Grandma” for Granna—the name we lovingly used for my great-grandmother, whose house was the venue for our variety show.

My time down South to Granna’s house always began in Cadillacs where I sat wedged between relatives—they were Great Migrators who’d traveled up from Virginia, coming at the tail end of the movement that brought about six million Black people north and west out of the South throughout the twentieth century.

We’d set out on our journey from New York in the quiet of the night, sometimes as early as 2 A.M. to get ahead of traffic. When we’d finally get to the house, we’d divide up into the rooms. I shared a room with my grandmother, Nana, filling the space between the wall and the mahogany bed frame with extra pillows so my little self wouldn’t get trapped. The sounds of crickets lulled me to sleep each night.

The part of Virginia my peoples are from has no beaches, just acres of land for farming and small brick houses. My great-grandfather built the family house by hand; it serves as the meeting place for everyone who comes for any and every occasion. For me: summer, Mother’s Day, Granna’s birthday.

We cousins played baseball, inspected salamanders and “garden” snakes, rode four-wheelers, and read books. Some days we’d even take long walks to commune with nature. In this part of the rural Virginia countryside, you had to create your own fun. The only phones that worked were landlines, and the television reception was intermittent. This led me to cultivate one of the best gifts a child possesses: an imagination.

After tiring myself out from playing, I’d run into the house and sit on the plastic-covered sofa. The sweat on my legs caused me to stick and there I’d relish in quietly observing grown folk’s business. I’ve always been fascinated by the intimacy of Black women’s lives, and there was no better place to develop that fascination than Granna’s house. My aunties were often in the living room gossiping about boyfriends, coworkers, and whoever else was getting on their nerves. Their candor equipped me with an ear for language. And when they’d leave the living room, my cousins and I would come in and set up shop. It was time to plan the variety show.

We’d write plays and choreograph dance routines. I wrote notes, lyrics, and doodles with my glitter gel pen. As an adult, and a professional artist, I now realize it was the beginning of what others call a process. In the seminal Black Women Writers at Work by Claudia Tate, Toni Morrison says: “Writing has to do with the imagination. It’s being willing to open a door or think the unthinkable, no matter how silly it may appear.” This quote crystallizes for me the ways that my gravitation to the arts was inevitable: Who I am now has always been within me, even as I continue to evolve.

Arguments about who should do what and when preceded extensive rehearsals. Eventually our family got tired of the ruckus and encouraged us to show them what we’d been cooking up (not till after dinner, though). Once we’d all eaten, we’d shuffle right over to the living room and move the furniture out the way to make room for the show. For the grand finale, we broke into a Get Lite era–style hand clap, a dance that was everywhere on the uptown streets we came from, while singing Granna her favorite: cooling water from Granna’s well.

As a daughter of the Great Migration, I was always thankful that my Nana and her siblings maintained their relationship with the place from which they came: the American South. It was here that I began the act of disappearing into myself to craft worlds, driven by what I think of as a deep wanting to know. I would close my eyes to imagine the stories I’d begun collecting on the ground. And I was going to great lengths to do so. When I thought no one was looking, I inspected the old wooden trunks in Granna’s room—a forbidden and sacred space—searching for anything that would tell me more. I can draw a direct line between those moments then and the sensibilities that have now allowed me to curate this issue.

Along the migratory paths they followed, South to North then North to South, my elders nurtured and poured into me. They fed the curiosity that would lead me to become a filmmaker, a curator, and, at the foundation of it all, a writer. The time spent in the Escalade on the I-95 coming and going, moments now long behind me, were all part of my education.

Guest-editing the Film issue continues that education. I’m thankful to Oxford American editor Danielle A. Jackson for allowing me to work on this project. The theme of this issue is Southern film, which necessarily includes films of the Global South. One issue can’t hold everything, but I’m deeply grateful for the breadth of stories we’re able to tell. Thank you to the entire OA team and, of course, to the contributors who poured their brilliance into these pieces. It was thrilling to see the thematic through lines that emerged: aspects of the maternal and notions of self-discovery.

I learned a great many things—Kasi Lemmons’s producer invited William Eggleston on set to shoot stills as potential promotion for Eve’s Bayou; Gloria Naylor started her own production company with the intent to produce adaptations of her own work; and Debbie Allen got her start as a director by knowing how best to shoot the dance sequences on Fame. I hope that maybe somewhere in these narratives you’re able to engage your own memories or gain insight into what makes film an art form I return to time and time again.