Toward a Radical Cinematic Horizon

The unrealized works of Toni Cade Bambara and Gloria Naylor

By Randi Gill-Sadler

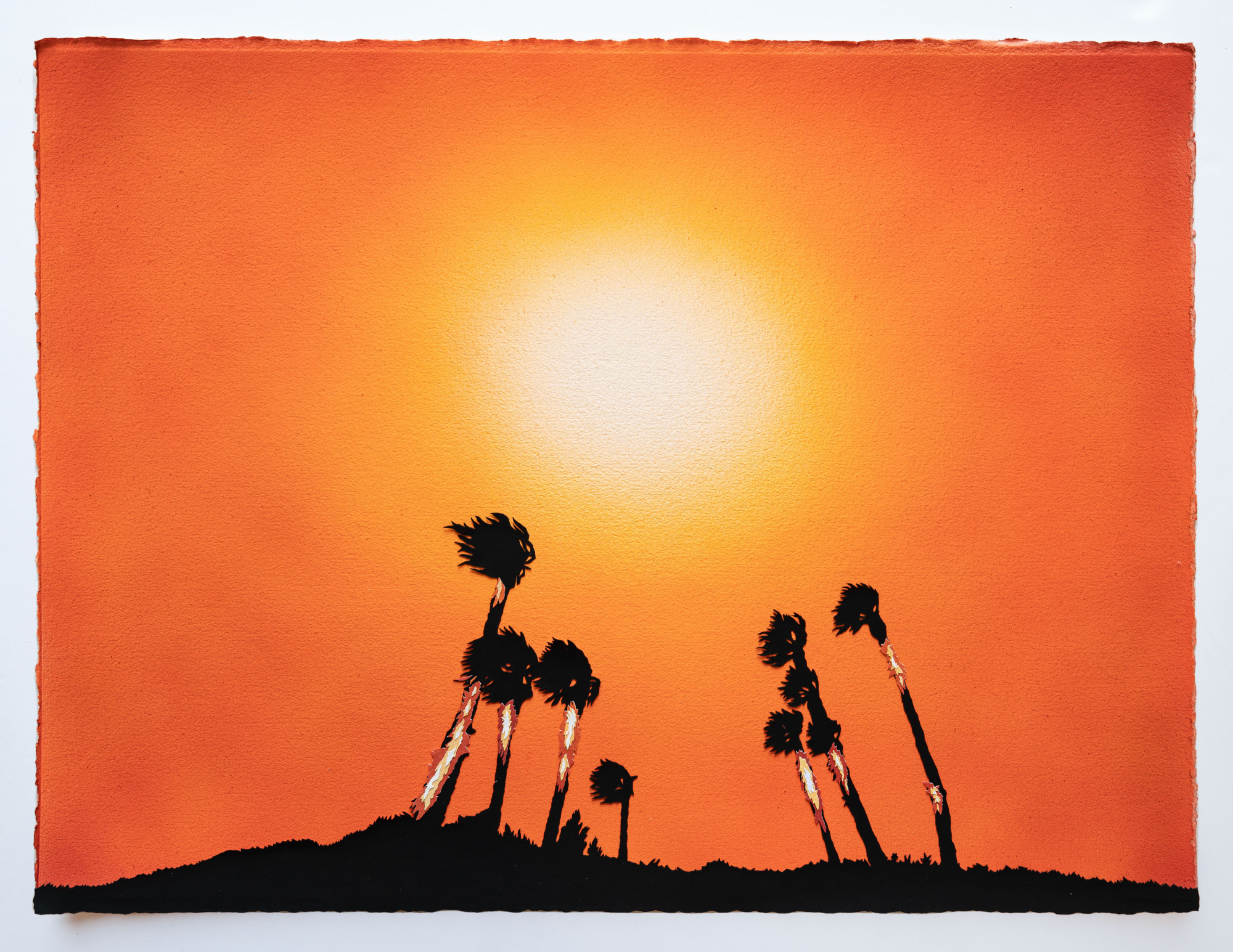

Mutation XLVIII, 2023 ink, gouache, acrylic, and colored paper on paper, by Francesca Gabbiani © The artist. Courtesy Wilding Cran Gallery, Los Angeles

In her 1987 Black-independent-film manifesto “Why Black Cinema?,” Toni Cade Bambara declares that “to be entrapped in other people’s fictions puts us under arrest.” The arrest Bambara highlights is not marked by traditional images of carcerality—police, handcuffs, prison bars—but rather the seemingly benign trappings of glitz, glamour, and celebrity associated with Hollywood, or “Hollyweird” as Bambara would call it. Three years later, Gloria Naylor, motivated by a similar impulse to reject the trap of Hollywood acceptance, started her own multimedia production company, One Way Productions. This was only one year after the television mini-series adaptation of her first novel, The Women of Brewster Place—produced by Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Productions company—premiered in 1989. “I realized that so often we are just the producers of things,” Naylor explains, “and we rarely control our own talents. So now I do.”

Toni Cade Bambara’s and Gloria Naylor’s rejections of the seduction of Hollywood in favor of supporting independent filmmaking mirror several decisions in their literary careers. These choices solidified their genius as writers and reflected their political commitment to imagine Black people’s liberation beyond mere inclusion into the untenable preexisting political structure. Bambara, the self-described cultural worker, used the sonic qualities and rhythms of Black people discussing politics on the Speakers’ Corner in Harlem to animate her first short-story collection, Gorilla, My Love. She also insisted, as editor, that The Black Woman: An Anthology, published in 1970 as one of the first collections of Black feminist writing, be pocket-sized, be affordable, and include the Black women organizers’ and community organizations’ writings and position papers. Rejecting the formal requirement of linearity for novels and the political peer pressure to believe in the inevitability of progress post the civil rights movement, Bambara published The Salt Eaters, her first novel, in 1980 and posed one of the most enduring and iconic questions of African American literature: “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?”

Naylor’s first four novels, published between 1982 and 1988, demonstrated her genius as a literary world-builder. Often polyvocal in narration and non-linear in structure, Naylor’s novels evince a dynamic portrait of Black life that troubles many liberal narratives of Black freedom. In Linden Hills, for example, Naylor uses the structure of Dante’s Inferno to unflinchingly present the titular Black middle-class neighborhood as a hellscape in which the depth of one’s assigned circle of hell coincides with the depth of one’s commitment to bourgeois values. In a different vein, Naylor creates the fictional island of Willow Springs in Mama Day to speculate about an alternative process of Emancipation that results in a rural, Black island community where “America ain’t entered the question at all when it come to [their] land” in the face of the real dispossession of Black people in the Sea Islands.

These literary works have solidified both Bambara’s and Naylor’s places within the period known as the Black women’s Literary Renaissance. Their place in the history of Black independent filmmaking is not as widely known. Their deep commitments to independent Black cinema would lead them both, independently of one another, to work with one of the most important Black independent filmmakers of the twentieth century: Julie Dash. Naylor worked as a production assistant on Daughters of the Dust, while Bambara wrote the preface to Dash’s 1992 book Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African American Woman’s Film. And while their respective literary oeuvres brought them mainstream and critical acclaim, their decision to make films independently resulted in several of their film projects being underfunded, unfinished, and ultimately unmade. The traces of these projects can be found in their archives in the form of funding proposals, screenplay drafts, and film treatments. Bambara’s screenplay and treatment drafts overflowed with handwritten notes in the margin, featuring everything from precise camera angle descriptions to meticulously edited dialogue. Naylor’s screenplays established the centrality of Mississippi to her cinematic storytelling as her archive holds screenplays set in Biloxi, Mississippi, and at Parchman Prison. Reading these drafts and proposals showed me that I could only know a portion of each woman’s brilliance by studying their published literary works. Despite having never been filmed, these nascent projects are integral to our understanding of both Bambara and Naylor as cultural workers and serve as urgently necessary moments in the history of Black women’s critiques of liberalism via cinema.

While she often credited the Speakers’ Corner in Harlem for providing her first lessons in storytelling and politics, Bambara first envisioned herself as a filmmaker while seated in the Apollo Theater watching what she described as “god-awful shorts with petrochemical eye-stinging colors” in between shows as a child. Bambara’s childhood dream of being a filmmaker would begin to take shape in the 1970s when she participated in filmmaking and editing workshops at the Studio Museum in Harlem under Randy Abbott and Ngaio Killingsworth. Although Bambara moved to Atlanta in 1974 to allocate more time to writing, she quickly became part of the Atlanta independent film community. She befriended Richard Hudlin, Cheryl Chisholm, and Louis “Bilaggi” Bailey, founder of the Atlanta Annual Third World Film Festival, and hosted visiting independent filmmakers and film viewings in her home. Even after leaving Atlanta, Bambara would continue to engage independent Black filmmakers critically in her writing.

Photo of Toni Cade Bambara by Carlton Jones for the W.E.B. Du Bois Film Project/Scribe Video Center

Her film programming and writing projects, however, came to an abrupt halt in 1979 during the Atlanta Missing and Murdered Children’s Case. Between 1979 and 1981 at least two dozen Black children and teenagers, and at least six adults, were murdered. Their disappearances and killings terrorized the city, especially Atlanta’s Black neighborhoods. Scores of local, state, and federal law enforcement investigators were assigned to the case. Instead of writing scripts and fictions, Bambara, alongside community members, began writing and circulating a newsletter to keep the community informed on where children had gone missing and where their bodies had been found. This newsletter proved invaluable, as Bambara and many Atlanta residents believed that the police were both negligent in updating the community and complicit in a campaign to spread misinformation about the victims and the state’s investigation. To counter the misinformation campaign, Bambara drafted a proposal to create a ninety-minute documentary on the Atlanta Missing and Murdered Children’s Case in the early 1980s. The proposal draft lists the directors as Bambara and Menelik Shabazz, the Black British independent filmmaker, educator, and founder of Black Filmmaker Magazine. The goal of the documentary was to highlight the discrepancy between reports from the media, the police, and Atlanta government officials and the narrative from community workers, civilian search teams, and independent investigators. Rather than perpetuate the fiction of Atlanta as a site of unfettered Black progress, evidenced in part by its Black mayor and Black police chief, Bambara and Shabazz sought to show a “city under siege.” Furthermore, the documentary would also showcase how Black Atlantans, in the face of governmental neglect, created alternative networks of care, research, and information to protect one another.

Bambara would ultimately opt to write a novel instead of producing the documentary. That manuscript, initially titled If Blessing Comes, would become the 1999 novel Those Bones Are Not My Child, edited and published by Toni Morrison after Bambara’s death in 1995. Even though Bambara never made the proposed Missing and Murdered Children documentary, her emphasis on community voices to contest the state’s “official version” of events no doubt shaped how she approached the 1986 film The Bombing of Osage Avenue. The film, a collaboration with Louis Massiah, documented the Philadelphia Police Department’s bombing of the MOVE organization’s residence, which killed eleven people, five of them children. Bambara’s documentary visions in both Atlanta and Philadelphia disabuse viewers of the assumption that Black leadership is inherently oppositional to liberal, classist, and anti-Black qualities of traditional leadership.

While the Southern leg of Bambara’s film work concluded in 1985, Naylor’s was just starting. Naylor began visiting Mississippi, Charleston, and the Sea Islands in 1985 to conduct research for her third novel, Mama Day. For Naylor’s mother, Mississippi mostly held memories of forbidden entrance into public libraries and Saturdays of all-day sharecropping to afford to purchase books. Yet in her visits, Naylor found an abundance of wisdom in elder Black women like Eva McKinney, a family friend. McKinney recounted stories of conjuring, herbal healing practices, and Black midwifery to Naylor. Those stories informed Mama Day the novel as well as the Mama Day screenplay and a screenplay for a half-hour TV drama titled M’Dear.

Gloria Naylor, 1992 © AP Photo/Tom Keller

Set in Mississippi, M’Dear is about mothering in an anti-Black world and conjuring as a means of retribution. It centers the relationship between Fannie, the mother of an ailing son, and M’Dear, an elder Black conjure woman. When Fannie rejects the sexual advances of a wealthy local white man, Jason Baker, he denies her access to the hospital and medical care for her son. Out of options, Fannie looks to M’Dear, to both heal her child and to “fix” Jason. Though M’Dear is at first unwilling, explaining it is God’s right exclusively to administer justice, when the child dies, Fannie demands: “And now is he God? We don’t keep breathing if he say so?” M’Dear is confronted with the limits of her conceptualization of justice in an anti-Black world and contemplates whether to take justice into her own hands, literally, in the name of family, even at this risk of her own damnation.

M’Dear rejects the expectations that Black people respond to anti-Blackness with long-suffering, perpetual forgiveness, or non-violence, in order to be viewed as legitimate victims, worthy of redress, in the eyes of the state or God. Indeed, that neither Fannie nor M’Dear even contemplate appealing to the state as a viable solution to Jason’s violence reveals their own understanding of the state’s incapacity for redress. M’Dear, then, offers a metaphysical reorientation to the question of justice from Southern Black women’s lived experiences and spiritual practices. What might Black pursuits of justice look like if they weren’t circumscribed by the need for salvation from the nation or God? Though Naylor received encouraging and supportive feedback from actors Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis on the screenplay in 1985, M’Dear never came to television screens. Naylor continued to develop a screenplay of Mama Day throughout the 1980s, expecting to have the film made by her own One Way Productions company. But in 2000, Naylor closed One Way Productions without having made Mama Day into a film; she died in 2016.

In the years since Bambara’s and Naylor’s passings, the entrapments that they unflinchingly called out and fervently contested have become more seductive and expansive and veiled to many audiences. Streaming services like Netflix and Hulu now feature categories for film and television like “Black Stories.” Viral hashtags and Twitter threads about the perpetual whiteness of film award season circulate annually. These instances appear to be victories or resistance, under the liberal standards of diversity, equity, and inclusion. But Bambara’s and Naylor’s unfinished but still important film projects remind us that Black independent cinema can do much more than lobby for inclusion. In a moment when literary and Hollywood markets are returning to Black women’s cultural production of the 1980s in the form of reissued novels and film remakes, Bambara’s and Naylor’s unfinished film projects, and the totality of their artistic oeuvres, demand a critical pause to consider the meaning of our nostalgia for Black women’s films and literature of the 1980s. Moreover, how has our understanding of Black women’s film and literature been overdetermined by the politics of Hollywood and mainstream literary culture? Rather than accept cultural standards that limit Black liberation to surface attempts of diversity, Bambara’s and Naylor’s unrealized film projects guide us toward more-radical cinematic and political horizons.