Horse Girls

Death, ponies, and the Local Honeys

By Madeline Weinfield

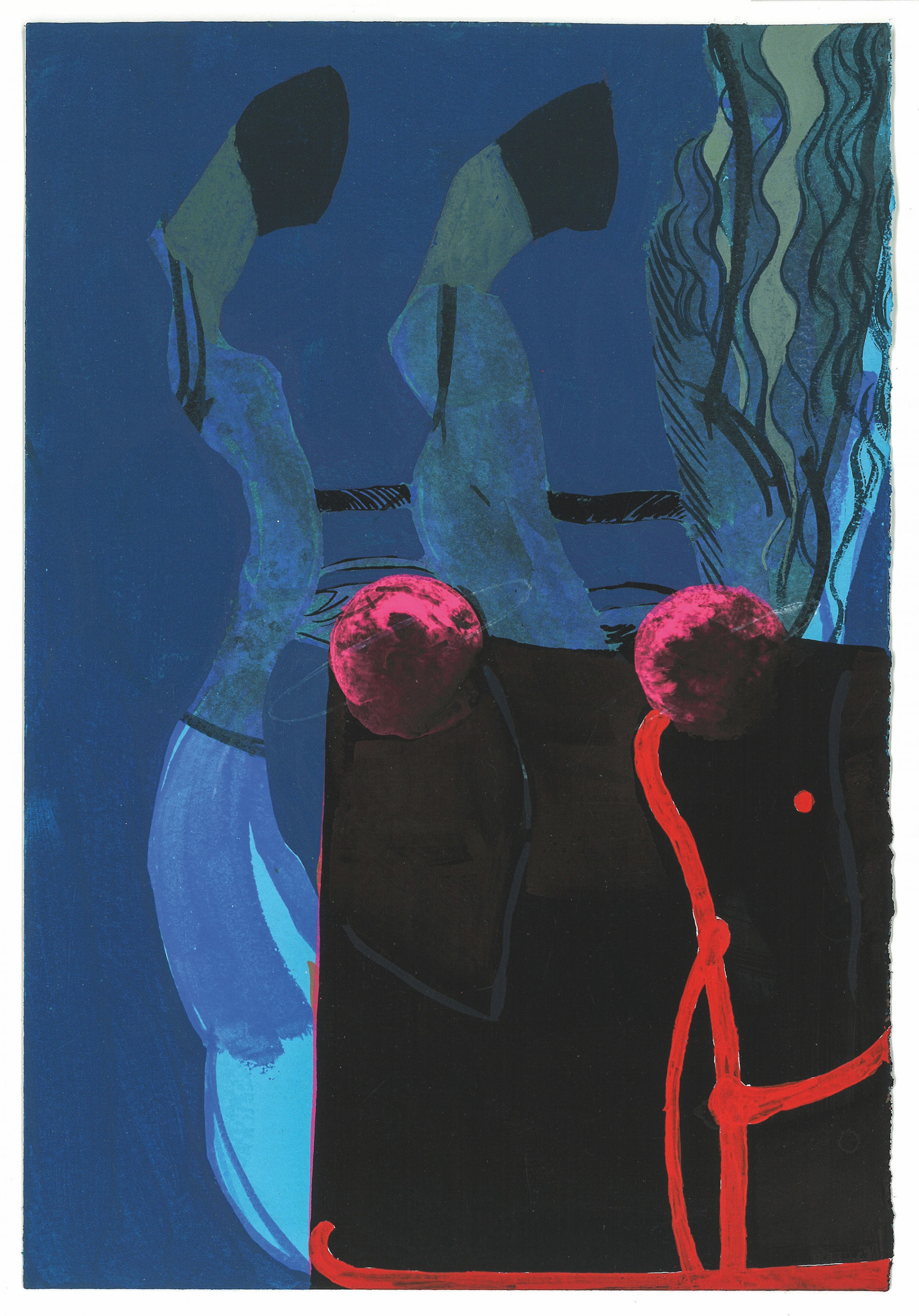

Mistigri, 2021, acrylic gouache on watercolor paper, by Judy Koo. Courtesy the artist

What do you do with something large and dead?

That’s not something I thought much about before hearing “Dead Horses.” The haunting, echoing ballad by the Local Honeys, a Kentucky-based country-folk duo, arrived in my life last summer like a knife; a stab from nowhere. Or maybe, more aptly, like a finger picking at an old wound that had been festering beneath the skin.

By the time I first heard the song and its plaintive, delicately harmonized chorus—I never got used to watching horses die—began to wedge itself in my brain, horses hadn’t been alive in my life for nearly twenty years. They belonged to the memory box of my childhood, confined to a young passion that had occupied a dozen years of weekends and a summer of camp. But the memory of them, like a first love, had branded me, and burns sometimes still.

Every line of the poetry Linda Jean Stokley and Montana Hobbs write for their songs is a layered contradiction—moody but not whining, country but not corny, full of death yet sung by voices fully, wholly alive. In the pared-down, bone-scratching songwriting of their self-titled debut album, they deliver songs that are searingly personal, reflecting the realities of farm life on “Dead Horses,” and the pain of the opioid epidemic in “Dying to Make a Living.” In writing these songs, in singing these songs, Linda Jean and Montana are writing and singing for themselves but also seemingly for you, and for me.

My life with horses had certainly been softer than the one the Local Honeys sing of. Certainly, I never watched a mare lying dead underneath a tarp out in the rain, or listened to her foal whinnying from its stall. Yet I keep listening to “Dead Horses,” to Linda Jean and Montana singing of the horses they loved and lost, of burying them in Kentucky farmland, of crying outside their barns. It’s Linda Jean’s voice that leads the melody. It’s soft and round, with a little fringe on the edges, like a fraying cuff on a pair of jeans. Together, with their close harmonies, finger-picked guitar, and clawhammer banjo, the Local Honeys pour out work that flows with sweetness and sting. The no-nonsense tradition of the bluegrass of Appalachia fills the jar, and you can still taste the remnants of the rich Kentucky soil.

This little girl inside me is chomping at the bit. She cannot save them all, a truth hard to admit.

Photo by Lila Callie Simpson of Lila Callie Photography, Clay City, Kentucky. Courtesy the artist

Listening to the insistent refrains of “Dead Horses” throws me out of the saddle and into the memory of the one I couldn’t save. His name was Zippy and he was anything but. I loved him for what I now realize was what I saw in him of myself: an in-between-age, awkward, lanky, black-haired, and thin-limbed as if our legs might crack if we ran too fast. He had once been a racehorse—registered as Maximum Zip—but by the time he found his way to me, eight years old and wild with love, a slow canter was his fastest speed.

One day, years into loving Zippy, I was told he had moved away. “Retired,” they told me, to a nice little farm. It wasn’t until I heard “Dead Horses” that I thought of this long-buried memory. Brought into the spotlight of years lived, I saw it for what it was, what it always had been, the opposite of what I had at the time accepted as the truth. And with the first listen of the song, I was a little girl again, mourning the loss of something large and dead. Of course, there had never been a farm. And there had not been a greener pasture for Maximum Zip.

Suppose we’re all just animals with slightly different hides.

For those not on farms, for those of us listening to “Dead Horses” in the tiny caverns of our rented apartments, the death of horses isn’t something we are bound to encounter. In the urban wilderness of an American city, animal death is a rat flattened on the road, a baby bird fallen from the nest in early spring. These deaths are small and meek, ubiquitous yet ignorable. A squirrel died in the attic of my rowhouse in Washington, D.C. An exterminator told me to leave it, let it decompose naturally over time, wait for the smell to pass, to expect just a small pile of bones. Below the eaves of the attic, I slept peacefully removed from the work of dealing with the squirrel and its death. But, even if I had had to bury the squirrel, I would have needed a small garden shovel, not a neighbor with a Bobcat, like the Local Honeys sing about.

Maybe something so large, so dead, is easier to swallow than the things that die without us knowing. I wonder if it would have somehow been easier to see Zippy, black mane poking out from under a tarp, dead out in the rain. Or maybe we tell ourselves that lie in order to survive.

In “Dead Horses,” Linda Jean sings as if horses dying is more beautiful than it is painful—an inevitability in life, like the leaves changing color in the fall and the snow melting in the spring. Montana backs her up, crooning in agreement. We grow older, they seem to say. Our mothers’ hair turns gray. Our hair turns gray; we are no longer little girls. Our horses die.

But we’re still chomping at the bit. Maybe that’s the truth hardest to admit.