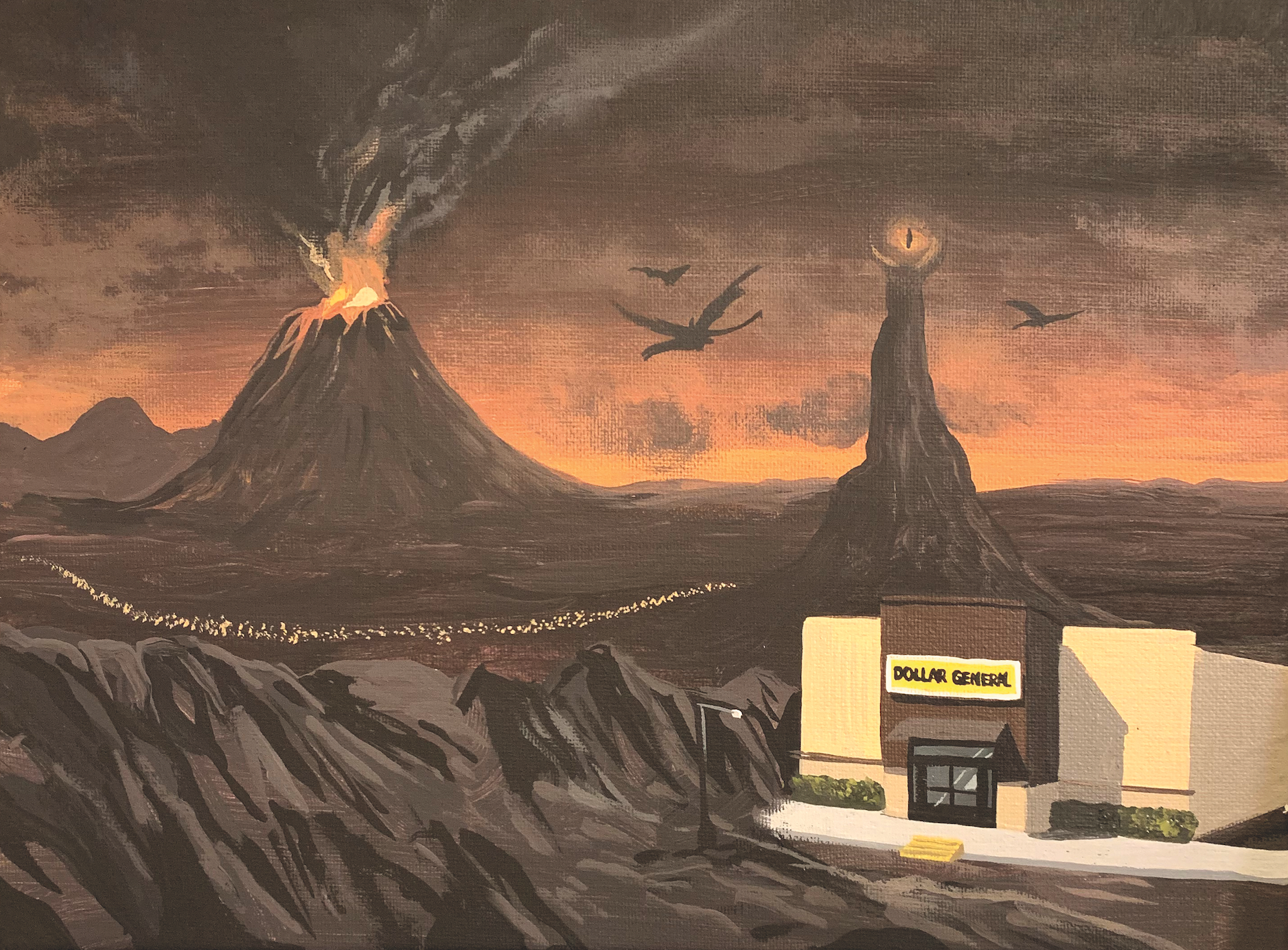

One Does Not Simply Walk Into Dollar General, 2023, a painting by Danial Ryan © The artist, @artofdanialryan

Inside the Dollar General Workers’ Fight for Safety and Fair Pay

These Louisianans are organizing to transform the stores their communities rely on

By Katie Jane Fernelius

Last summer, David Williams popped his headphones in and began listening to the multi-hour playlist he specially made for the eight-hour bus ride from New Orleans up to Goodlettsville, Tennessee. The playlist was a mix of hip-hop and r&b: Kendrick Lamar, Keyshia Cole, Usher. The kind of music that made David feel good, like nobody could stop him. It helped him get in the zone—which he needed to be in because he was on his way to disrupt the annual meeting of Dollar General shareholders, the third meeting he would attend in as many years.

At that point, Williams had worked for almost five years as an associate stocker at the Dollar General in his Holly Grove neighborhood of New Orleans. (A one-star Google review of the store reads, “Boxes blocked almost every isle [sic], the store was dirty, and one of the 3 employees was listening to music so loud you can hear the cursing in the lyrics.” But a recent five-star review is more resigned, reading, “I mean, it is what it is. It’s just the Dollar General.”)

When David started there in 2019, he had wanted a steady job close to home, but almost as soon as he started, he found the work exhausting. He’d spend hours unloading the stock into the store: a constant up-and-down-and-up-again of lifting and moving boxes down aisles and onto shelves, which always seemed to have simultaneously too much stuff and not enough.

There are an estimated 20,000 Dollar Generals across the country, making it the most prolific retail chain in the country, dramatically outnumbering Walmarts, CVS pharmacies, and McDonald’s across America. And where there is a Dollar General, there often is little else, which, for certain communities, makes shopping and working there feel less like a choice and more like the only option available.

In the last decade, dollar stores have become a cause célèbre of national media, receiving substantial coverage from outlets as distinct as Bloomberg Businessweek, ProPublica, and Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. This coverage has documented the rapid expansion of dollar stores into the neglected corners of America, primarily small, rural towns and poor, urban neighborhoods—or, as one worker told me, “food deserts” and “the hood”— becoming the modern-day equivalent of a general store for cash-strapped households with few alternatives.

Media narratives of dollar stores can be kaleidoscopic: Seen from one angle, dollar stores are one of the few stores committed to serving otherwise under-served communities. But seen from another angle, dollar stores have become embodiments of the failed utopia of cheap consumer goods that have long buoyed the so-called American Dream, offering worse versions of familiar products—think slightly tinier tubes of toothpaste or scratchier beach towels at fewer square inches— for cheaper prices undergirded by corporate neglect and poor wages, which, in turn, make the stores more susceptible to violent crime.

David often felt on edge at his store, like something bad was about to happen. One particularly warm day, someone walked in wearing a balaclava, which David clocked as unusual for the weather, and started pacing up and down the aisles. David wondered whether the person was about to rob the store, something he knew to be not at all uncommon at dollar stores. But then the intercom came on—“loud as hell,” David said—and the person ran out. David guessed that the noise had spooked them.

Then, the week before Christmas, he woke up to a phone call from his cousin alerting him that the store was on fire. David jumped out of bed, put on his shoes, and walked down the street, where he saw smoke billowing up into the sky. As he neared Earhart Boulevard, he saw flames engulfing his workplace.

Later, David would learn that the layout of the store, labyrinthine from the sheer volume of stock inside, helped keep the fire burning for almost five hours before over five dozen firefighters managed to extinguish the blaze. But that morning, David only had two thoughts. His first thought was: I hope nobody is inside. His second thought was: I need to find another job. For the next six months, he worked at a different Dollar General downtown, until he could transfer back to his Holly Grove store, which by then had been reopened as a DG Market, a slightly more “upscale” version of Dollar General that carries fresh produce—and the company’s answer to the persistent criticism that their stores drive the creation of food deserts (areas without easy access to fresh, affordable groceries).

In some ways, Dollar General could be considered the natural successor to Walmart, despite being over twenty years its senior. Both are companies born of the American South and what scholar Bart Elmore has called “country capitalism,” an approach to business perfected by Coca-Cola, FedEx, and, yes, Walmart. All specialized in servicing rural communities, in part by figuring out how to make their businesses efficient “conduits of capitalism,” streamlining supply chains to quickly move and distribute stock across a wide terrain and into remote areas.

In recent decades, Dollar General, which started in Kentucky and continues to have a strong foothold in the South, similarly imprinted itself on the American landscape by putting stores where there were few other options and offering lower prices than the nearby mom-and-pops. It is this tactic that has led to credible accusations that Dollar General, like Walmart, has played a role in creating food deserts by eating up the thin profit margins of nearby grocery stores. These stores often make their money through center-of-the-store purchases of nonperishable items like cake mix and canned foods, which Dollar General typically offers at a cheaper price. And Dollar General, like Walmart, has benefited from a “lean labor model,” a business school euphemism for employing as few people as operationally necessary, typically at low wages. (In fact, one comprehensive study found that when a Walmart opened in a town, it led to an increase in poverty by contributing to the closure of other local businesses and offering lower wages to fewer people.) According to the Economic Policy Institute, approximately ninety-two percent of Dollar General workers earn under $15 per hour—the worst rate among more than five dozen of the largest retail and food service firms in the country.

Not too long after the fire, a man named Greg Wilson called David. He was an organizer with a local advocacy group called Step Up and had gotten David’s number from a former coworker. He wanted to know whether David might be up for meeting sometime and talking about his job at Dollar General.

David met Greg at a park near his house. Greg struck him as intense, yet, from the start, the conversation felt genuine and unforced.

“And then as we started conversating, details started coming in about what really goes on behind closed doors with these stores and our companies, how they really treat dollar store workers,” David said. “And the more I started to know about all this, the more I wanted to do something about it.”

Greg told David that these dollar store companies had a bad track record in how they treated both their workers and their customers.

Greg told David that these dollar store companies had a bad track record in how they treated both their workers and their customers. That New Orleans and Louisiana were becoming the center of a concerted effort to organize dollar store workers. That someone in Alexandria, Louisiana, had spoken up about the company’s failure to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) for her during the early days of the pandemic and even published an op-ed in the New York Times. And it had worked. The company had caved on its initial denial of her request and finally provided some PPE for its workers. It was possible to win.

So, Greg asked, would David like to join a group of workers who were trying to change things, trying to win?

Yes, David said, he would.

Just months later, David would make his first journey up to Goodlettsville, a small suburb just north of Nashville that is home to the headquarters of Dollar General. On the morning of the meeting, dozens of workers and organizers descended on the City Hall, where the shareholders were scheduled to convene, hoping to gain entry and demand better conditions at the stores. But security turned them away.

The next year, in 2023, they came better prepared. They got the right paperwork in hand to be official proxies, meaning they had a legal claim to sit in on the meeting on behalf of some activist shareholders. David was one of three workers who gave a three-minute speech calling for improved safety practices for employees. On his way over to the meeting, he listened to Rick Ross to prepare, because he wanted to feel like a “boss in my own domain.” He doesn’t remember exactly what he told the room full of assembled shareholders, but he remembers trying to speak quickly and make eye contact with everyone in the room.

“I tried my best to say every little inch of every word,” David said. “And put a little spin on it myself.”

His time ended before he could finish reading his statement. But the workers’ statements seemed to have an impact. That same meeting, the shareholders would go on to pass the workers’ proposal for safety, calling for an independent audit of how the company’s practices contribute to safety concerns.

It felt like a true victory to David.

“As many times as I’ve failed in life, I felt like this was the first time I’ve actually worked as hard as I possibly could to be a part of something big and it came out victorious,” he said.

But last summer, in 2024, when David bused up to Goodlettsville for his third year of shareholder meetings, he wasn’t quite feeling himself. At some point during the eight-hour journey, during his multi-hour playlist of Kendrick tracks and the crooning of Usher, he came down with a stomach bug. That night he holed up in his hotel room in Tennessee, urging himself to get better in time for the planned actions the next day. This year’s demonstration was set to be the workers’ largest move yet.

In the time since their last protest, the board of Dollar General had ousted CEO Jeff Owen and brought back Todd Vasos, who had helmed the company from 2015 to 2022 before retiring. During Owen’s brief tenure, which didn’t even last a year, Dollar General’s stock prices had stagnated while public scrutiny appeared to climb. For the organizing workers, this was an opportunity to press even harder for change, as Vasos was expected to rehabilitate both the reputation and stock price of Dollar General.

The workers had won a safety audit the previous year, but Dollar General had hired a union-busting law firm to conduct the investigation, leading Step Up to call the resulting audit a “sham.” This year, the workers wanted to apply pressure on the newly reinstated CEO and push the company to commit to meaningful action to improve safety and pay across the board.

Sick in his hotel room, David knew this was a crucial moment. “I really became emotional,” he said. “Because, man, I really wanted to do this. I really wanted to be there and make my presence felt. And at that moment I felt like I was letting everybody down.”

The other organizers comforted him, gave him medicine, told him he wasn’t letting anyone down. It made him realize he was loved and cherished, that this fight was bigger than him. And when he woke up the next morning, he no longer felt sick; he just felt ready to confront the Dollar General leadership.

“I said like, ‘Yeah, they in trouble,’” David said. “They should have wished at that moment that I was still sick. Nah, I ain’t about to miss this.”

That day, the group of more than two hundred workers and advocates rallied in Goodlettsville before marching to the Dollar General headquarters, which was on lockdown in anticipation. Inside, where David was present as a proxy, the protesters’ chants could be heard.

At one point during the shareholder meeting, David found himself in a conference room eye to eye with Todd Vasos.

They shook hands.

According to David, Vasos told him that he was remarkable and brave for speaking up at the shareholder meeting last year. But David bristled at Vasos’s compliment; he wasn’t looking for praise, he was looking for changes. Vasos then told David that the company was doing its best to make the stores safer for workers like him. But David was skeptical of Vasos’s polite promises and told him as much.

“With all due respect, it’s more about action than speaking, ’cause actions speak louder than words,” David told him.

At the time, company leadership seemed cautiously amenable to the workers’ demands, providing a statement to a local news station saying that they “value feedback and will continue encouraging our employees to share both positive and constructive feedback in company-provided channels so we can listen and collaboratively address concerns.” (A company spokesperson shared the same statement verbatim with the Oxford American when contacted for comment.)

Months later, as if heeding David’s words, Dollar General would let its actions speak louder than words. It shut down five stores, all in New Orleans East, a large expanse of the Ninth Ward that juts out like a crab’s claw between Lake Pontchartrain and the marshes leading out to the gulf. It’s home to some of the lowest-income neighborhoods in the city. The move was a rare contraction for the retail giant that otherwise appeared to be expanding its footprint nationwide—and a move that David and other local workers read as retaliation against their organizing.

Dollar General contested this. In a statement to the Oxford American, a representative for the company said its decision to close those five stores resulted from an “evaluation of operational effectiveness” and was not related to the organizing done by David and other workers in the city.

Still, David remained skeptical.

“It’s already limited out there in the East, and you taking those jobs and those opportunities away from people?” David said. “I guess it was their way of showing retaliation towards us because we were doing way too much talking.”

“It’s already limited out there in the East, and you taking those jobs and those opportunities away from people?” David said.

Kenya Slaughter. Photograph © Rita Harper

When Kenya Slaughter first applied to work at Dollar General in 2018, she was a new mom living in Alexandria, Louisiana. She needed a quick job, close to home, that didn’t require a college degree.

“Something that was attainable in the moment,” she said.

The Dollar General in her neighborhood seemed to fit the bill. But soon after starting, she found herself in the ninth circle of retail hell.

One time a customer came in and defecated while standing at the register; it dripped down their leg and onto the floor. Another time, a woman ran into the store with a machete and locked herself in the break room. Kenya stood outside the door, trying to talk the woman down, “hoping that she wouldn’t open the door swinging.” Then there was the day that Kenya picked up what she thought was a Honey Buns wrapper; it turned out to be a used condom.

“I was so freaked out, I went and bleached my arms up to my elbows,” Kenya said.

Such disturbing and visceral images are not out of place in accounts of dollar store workers, often alongside phrases like “rat feces” and “obstructed fire exits” that would alarm any employee of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (In July 2024, Dollar General agreed to a $12 million settlement with OSHA, as well as committing to measures to improve safety, after the government watchdog designated the retailer a “severe violator” of federal law.)

But it wasn’t just the gross-out moments that got to Kenya. It was the fact that despite being hired as a cashier, she was expected to take on work that, in a better-staffed workplace, would be done by other people.

“If I’m hired as a cashier, then I should be cashiering,” she said. “I shouldn’t be stocking. I shouldn’t be a janitor. I shouldn’t be security. Yet, I find myself doing all of those things.”

Her frustrations with work came to a head in 2020 when COVID lockdowns shut down most of the country. Kenya was surprised to discover that she, along with front-line nurses, delivery food drivers, poultry factory workers, and bank employees, was part of a newly minted category called “essential workers”—and, therefore, was expected to continue going to work. But, despite the fact that she would be doing customer-facing work during the height of a pandemic involving a highly contagious virus, she felt like Dollar General was not providing her adequate PPE. She wanted more gloves and masks. She wanted plexiglass in front of the register. And she wanted paid sick leave.

By that point, Kenya was no stranger to raising a ruckus. She had become a regular at city council meetings in Alexandria, then got involved in a mayoral campaign. That led her to join a statewide community organizing group called the Power Coalition, which then led her to give testimony at the state capitol on behalf of retail workers in 2019. Kenya spoke in favor of a bill that would let Louisiana parishes establish their own minimum wages, which state preemption laws currently prevent them from doing.

So, in 2020, faced with an employer denying her adequate PPE, Kenya wasn’t shy to speak out. She decided to volunteer her perspective to a journalist at the New York Times.

“I had no idea that that story was actually going to get published and gain all the attention that it did,” she said. “But nevertheless, that landed me the op-ed in the New York Times.” The op-ed went modestly viral and contributed to a wave of reporting on dollar stores across multiple outlets. Kenya soon became one of the go-to sources for the experiences of dollar store workers.

Still, in spite of this coverage—or rather because of it—Kenya found it difficult to organize her coworkers in Alexandria.

“Everyone was basically afraid,” she said. “No one wanted to talk to anyone, especially after I was in the paper. It was like, ‘Oh lord, you’re on TV. You in the newspaper. Uh-uh. I can’t do that.’”

It surprised Kenya because she felt like she was walking proof that the more you spoke up, the less that Dollar General leadership could do to you. After all, she hadn’t been fired. Her hours weren’t even cut back. Nothing bad had happened to her so far.

“If you kind of play the fence and be on the sidelines, that’s when they can try and attack you, but when you’re that visible, they’re going to look bad [if they come after you],” she said.

Still, she understood that asking people to put their necks on the line at their jobs could be a scary proposition.

“It’s their bread and butter,” she said. “Nobody wants to lose the way they pay their bills and care for their children.”

But, I asked her, wasn’t the pay just crumbs anyway?

“Yes,” she retorted. “But those crumbs are helping them get by.

For people looking for a new era of labor power after the pandemic, the new status quo might feel like it came from a dollar store: a cheaper, worse version of itself.

There was a brief moment in the long unfurling of the pandemic when it seemed like the half-century tide of active animosity against labor power, which had seen American workers face one deadening loss after another, might have finally turned. Countries began locking down in response to the threat of the novel coronavirus. The American government, likely fearing an instant and crippling recession, began giving its citizens money and dramatically expanding the social safety net. As a consequence of these policies, poverty fell to its lowest rate in over five decades. There was a surge in both efforts to unionize and public support for unions.

But then came the backlash. Executives bemoaned the fact that, according to them, no one wanted to work anymore. There was even a name for it, the Great Resignation, as if millions of workers had been raptured out of the economy. Turns out, many just went on to better-paying jobs. As the economy (slowly, allegedly) recovered, and as the pandemic entered the rearview mirror of public consciousness, many of the most popular and successful pandemic-era supports ground to a halt. The strong labor market dipped. And the once-hailed victories of social policy curdled into the memory of a brief reprieve—a temporary salve, at best—instead of the foundation of lasting change.

Dollar stores are among a pantheon of American companies—from Walmart to Amazon to Uber—that have become recurrent metonyms for the changing American economy. For people looking for a new era of labor power after the pandemic, the new status quo might feel like it came from a dollar store: a cheaper, worse version of itself. A specter is haunting Dollar General—the specter of a union. A Dollar General spokesperson told the Oxford American in an email, “We firmly believe our employees are best served through open, direct communication with the Company and do not believe that interjecting a third-party into this relationship is in our employees’ best interests.” In recent years, the company has come under fire from the National Labor Relations Board for retaliating against a union campaign in Connecticut.

However, not in one interview for this story did I hear one worker actually discuss unionization.

“We wanted to empower workers at a faster pace,” Greg Wilson, the organizer who first contacted David, told me. Greg is no stranger to unions. He spent decades organizing the hospitality sector in New Orleans, his résumé a litany of hotels. He knew how time- and resource-intensive a union campaign could be, especially in stores known for high turnover. So, he figured, what if the workers instead just acted like they already were in a union?

It was a bold strategy, especially in regard to Dollar General, where workers often feel like they have few, if any, other options for employment. It was also a bold strategy in the South, where unions have historically been suppressed and face greater hostility from state governments.

“They [Dollar General] come into the community and they make promises and it’s not kept. And what it does is it pulls down morale, like ‘This is the best that we can have,’ or we grow dependent on thinking that this is all that they have to offer, all that we can get in this community—which isn’t the truth,” Greg said.

In 2017, an analyst told Bloomberg Businessweek that “essentially what the dollar stores are betting on in a large way is that we are going to have a permanent underclass in America.” Dollar General’s business model relies on both its customers and workers being disadvantaged; the company has long benefited from a model of Southern economic development that depreciates labor power, and therefore wages, across the region.

So, how do you turn the tide? Do you uproot the Dollar Generals because their economic model is fundamentally flawed? Or, recognizing their ubiquity, do you try to push them to change?

“I think there’s a stigma that we want to shut them down, and that’s not the case at all,” Kenya, the Dollar General worker from Alexandria, said. “We want them to do right by their employees, do right by these communities, do right by our people. Because these stores are in neighborhoods where there are people that look like me. And I want them to have a fair chance.”

Kenya described her ideal Dollar General as being well-staffed, clean, and secure, with fresh food. Basically, a miniature Kroger or Albertsons, she said, with good pay. She knows it’s possible. She actually left her Dollar General job in Alexandria to work full-time as an organizer on the campaign. Right now, the strategy is to press on Dollar General from all sides: shareholder meetings, OSHA, even the National Labor Review Board—or whatever semblance of these still exist under the Trump administration.

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t an appetite for exercising direct labor power. One young, recently organized dollar store worker told me that “it would be so fun if we just stopped working and yelled at the managers,” but then quickly acknowledged that a strike was not on the table at the moment.

“This is where organizing gets hard,” Greg said. “Because we have to ask: what’s it going to take for us to get what we rightfully deserve?”

This story appears in the Summer 2025 print edition as “Too Much and Not Enough.” Order the Y’all Street Issue here.