Making Paradise

By Austyn Gaffney

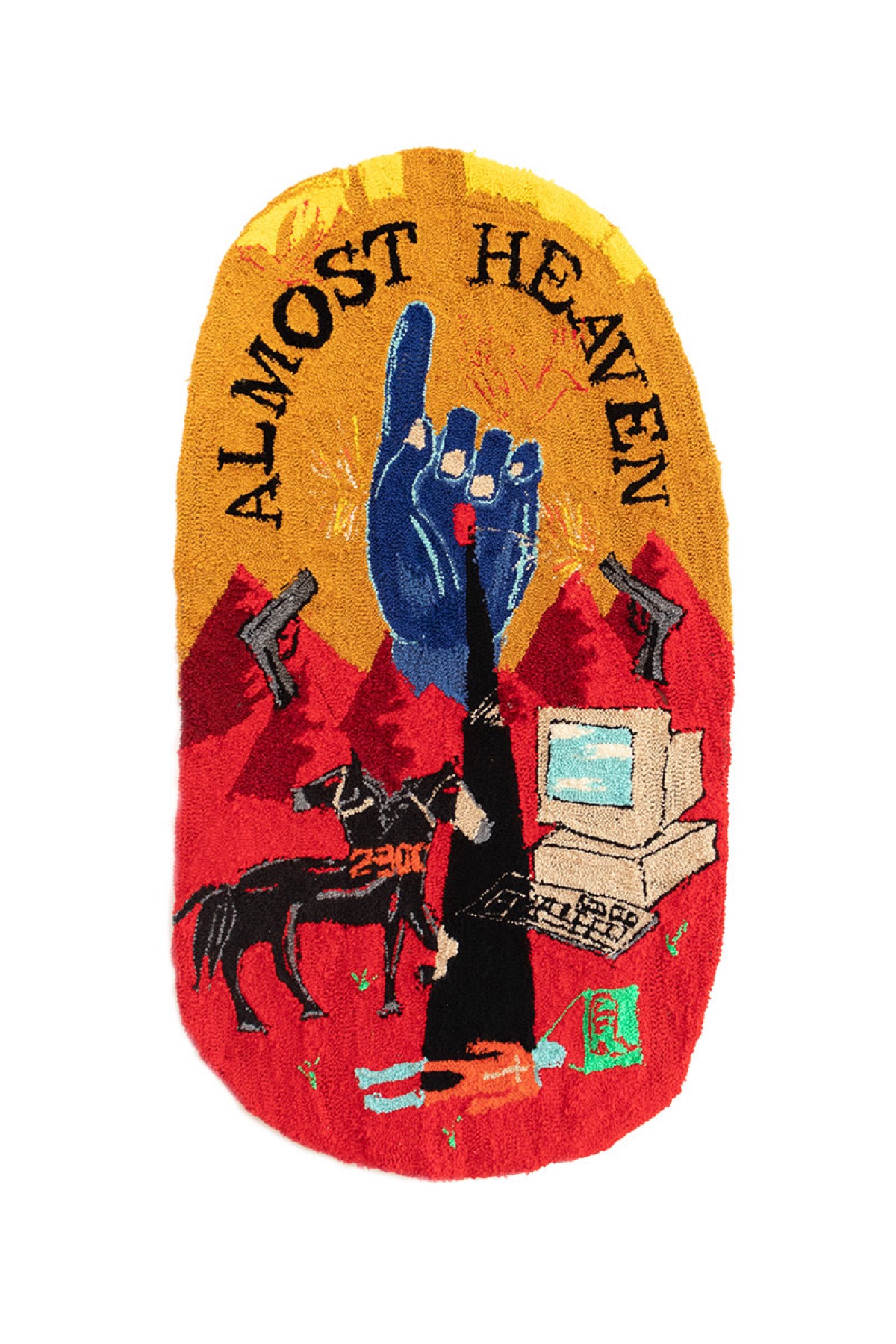

"god's hand," recycled yarn and monks cloth by Molly Z. G. Courtesy Institute 193

For almost four years, Molly Z. G., (who uses they/she pronouns; both are used here), a textile artist and social activist in southwest Virginia, has had a recurring dream that goes like this: They’re in a large room, looking down on their own arms holding themself. There are various iterations of this scene. During one dream, Molly sees a mass of semi-adult Mollys holding a lot of Molly babies under a domed ceiling, “like if I held a convention,” they said. Sometimes she is a non-descript baby. Sometimes it’s toddler-Molly with blond ringlets like Shirley Temple. When pressed, they put forth a theory, like the dream means they talk to themself a lot. (“I have a very strong internal monologue.”)

Molly is twenty-five and a Leo (“I don’t understand astrology, but it is fun”), on the cusp between Millennial and Gen Z, and, for now, a maker of brightly colored, dystopian rugs that range from sink-sized carpet squares to wearable overcoats. Their art studio is also their bedroom. They live with several roommates in a ranch house at the end of a cul-de-sac in suburban Blacksburg, Virginia. When I visit in early November 2021, Molly lies diagonally across her bed, on top of a thrifted quilt that stitches yellow, rust, and tiny floral blocks together like a late sunset. Molly’s fashion is also pure thrift store, what she describes as her own “Dad” style: oversized plaid shirt, loose black jeans, and chunky shoes. Their short brown hair is tucked behind their ears and their arms are folded across the bedspread, framing an inquisitive, open face.

Molly has lived in Blacksburg, in the heart of Appalachian Virginia, for seven years, staying after graduating from Virginia Tech with a degree in political science. Their room still looks much like a college student’s, complete with a dead pawpaw plant by the window. I sit cross-legged in front of floor-to-ceiling IKEA shelves overflowing with crafts: excess fabric, spools of ribbon, canvas, zippers, stacks of pens and pencils, failed rugging projects, dozens of skeins of yarn, hundreds of bottles of scents and homemade perfumes. She still has her mother’s embroidery machine, shelved between a blue cardboard trove of The Original Poly-fil and a box devoted to sentimental memories.

Then there’s Molly’s rugging frame leaning against the shelf wall, a swaying six-and-a-half-foot square that Molly refers to as her “room hazard.” The frame, along with two smaller copies, is lined in two rows of pink carpet gripper tape to keep the canvas taut. For each new project, Molly sources recycled yarn, yarn from thrift stores, or yarn at deep discounts from couponing at JOANN Fabrics. After drawing a design in Photoshop, Molly will project it onto the canvas, sketch it out, and plan the color scheme. Her tufting guns, the length of her forearm, are obnoxiously heavy and loud. Molly dons noise-canceling headphones before choosing the right gun (cut pile or loop pile), threading it with yarn, and wrapping her left hand around a black plastic handle while placing a finger on the trigger. Her right hand steadies the front of the blue gun by holding a black knob like a rudder. Two prongs surround the tufting gun’s needle, much like a pair of buckteeth, to keep the machine steady against the canvas. Then, under a constant stream of metallic buzzing, Molly will paint with yarn.

From an overflowing box, Molly pulls out a failed example of one rug meant to recreate the many-Molly dreams. Against a stained-glass-window backdrop is a portrait of Mary, mother of Jesus, with a blue face, pink cheeks, and a spiked gold crown. The design is reminiscent of much of their best work: rugs that are bold and irreverent, mixing bright primary colors with rough-hewn shapes, figures, and symbols that achieve a messiness that feels somehow lucid and very real.

But Molly flubbed an attempt to render Mary holding Jesus. Instead, Jesus’s baby-sized form looked like a blue worm emerging from a slit in Mary’s red robe. His wormy body ended up looking like a third arm, which ended up—due to placement and its tubular nature—looking like a penis. As a remedy, Molly covered Jesus’s face with a faded picture printed onto an old tote bag of an adult Jesus wearing black sunglasses like The Dude in The Big Lebowski.

Years before Molly fell in love with their home in southwest Virginia, before they challenged the U.S. legal system in environmental protests, before they denounced their prescribed heterosexuality, Molly was a Catholic. She spent the first half of her life in Catholic school in Pittsburgh, sporting a mix of red, white, and blue polo shirts and khakis and shuffling into church pews three times a week.

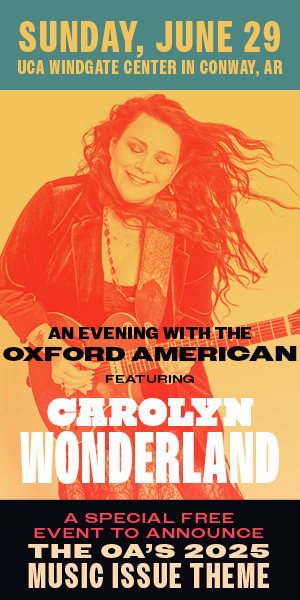

While they no longer practice, Catholic iconography and storytelling—and the humor Molly now associates with organized religion—define much of Molly’s current work. So when Molly was invited to present their art at Institute 193 in their first solo show, displayed for a month following the opening on October 7, 2021, they tried to make rugs with very serious and explicit ideas about theology and Appalachia and labor.

“But [those ideas], they didn’t all translate well, so they all kind of changed over time,” Molly tells me, looking down at Mary, unsure if an audience would find the altered, absurdist version as funny as she did.

Yet that sense of humor is what attracted Phillip March Jones, the founder of Institute 193, a narrow exhibition space in Lexington, Kentucky, documenting contemporary art in the South, to Molly’s work in the first place. (He took notice after Molly posted a rug styled after a bottle of Crystal hot sauce on Instagram in May 2020.) March Jones tells me that he was drawn to their aesthetic, which he describes as “weird and campy and smart.”

The two began talking over ideas for Almost Heaven :^), a mix of out-there textiles, scents, and wearable art set up like a boutique storefront: Plastic mannequins are dressed in rugs fashioned into cropped jackets of big red hearts; four horse-head purses made from yarn and monks cloth hang from a wall (“I want it on the record that I did not know Lexington was so much about horses... I am embarrassed to add to the propaganda.”); stained-glass sanctuary windows replicated in fabric feature horned demons and nuns crying blood and blond girls with knives through their eyes. In a corner of the gallery, Molly installed a vintage pinball machine on thin, teal plastic legs. They soldered in electric misters, like those in oil diffusers, so when the ball bounced between bumpers, the machine could emit different perfumes. A sparkling command below a glued-on cross read: “Enjoy this pinball game or BURN FOREVER.”

Like all kids, Molly thought the world revolved around their home, and until they turned eighteen, home was the Catholic-majority city of Pittsburgh, replete with a statue of Joe Magarac bending steel beams at Kennywood amusement park, a seemingly endless supply of perogies, and their four-year-old brother pulling Fred Rogers into their church’s baptismal pool.(“Everyone in Pittsburgh has a Fred Rogers story.”)

Molly’s parents worked in Pittsburgh steel mills until the factories shuttered. In their early twenties, her parents had moved separately to Roanoke, Virginia, about twenty-five minutes east of Blacksburg, where they met after graduating college. After Roanoke’s own steel mills closed, the young couple returned to Pittsburgh, where Molly was born. Molly’s dad became an electrical engineer for General Electric; their mom stayed home until Molly reached fifth grade, and then became an accountant.

Molly shared one of their earliest rugging projects as a GIF on their Instagram account: a giant cream rug sewn into an overcoat with a blue cross over the back and orange flames rising up the front. The coat dances in front of a looped video of an overflowing tank of bubbling, fiery steel; it looks alive, twirling and waving thin red arms up and down like a revivalist. The rug, called where do we go when we die? pittsburgh?, was inspired by one of Molly’s favorite movie series, the Terminator franchise, which she watched over and over as a kid. She equated the lava that android Arnold Schwarzenegger melted into at the end of the second Terminator to the steel mill where her parents once worked. Molly peacefully dreamt of melting down. As a kid, she imagined that’s what happened when you died: You melted down, you became steel.

But her mom was raised a devout Catholic and quickly set Molly and her older brother on the same course. This set of strict beliefs lasted until Molly was fourteen when, during a church-led summer trip, a flood of teens walked one-by-one up to an altar and broke down crying, claiming God spoke to them. When Molly joined the weeping mass, she cried for a different reason: She couldn’t hear God. Before that summer, an anonymous girl a grade above them in Catholic school had accused their priest of sexual assault. Molly was disillusioned. After Molly was outed by her older brother for her lack of faith at age fifteen, she says her mother stopped talking to her.

“My parents shunned me for like four months. They took the door off my room Freaky Friday–style,” Molly says. Molly went through a militant atheist phase, where they made custom tees with Richard Dawkins quotes. Old friends at Catholic school told Molly she was hell-bound. “The idea of eternity or going to hell forever just became so stressful that it was almost funny,” she says now.

Molly doesn’t think their parents remember the time they took the door off the hinges, or stopped speaking to them, or considered pulling them out of therapy when they were eighteen, the year Molly moved to Virginia for college. “I have all these things I want to have conversations with them about, but after I’m off their health insurance,” Molly says laughing. Molly’s own queer identity is one of those topics, but Molly says it’s hard to find the right language to talk to them about it.

Molly first turned to rugging after graduating from Virginia Tech, around the time they ended their relationship with a man they allege sexually assaulted them. As a distraction from their complicated grief, in September of 2018, they drove three hours east to cry in a friend’s Richmond apartment. Every day of their visit, they forced themself to leave the house and walk through the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where they would cry some more, first in the cafe, then wandering between exhibits. Near the end of their stay, Molly saw a rug hanging off a white wall, and thought, Damn, I’d love to make a rug.

They immediately solicited advice from a popular rugger on Instagram. Back home, they built their own frames and learned techniques on YouTube. Eventually, they installed a bedroom doorbell so their roommates wouldn’t startle them by entering unannounced, causing them to impale themself with the rug gun. Over the course of almost three years, Molly has made close to sixty-five rugs. They’ve developed tinnitus in their left ear and carpal tunnel in their left hand.

Most of Molly’s small profits from rugging go back into various social justice movements. Her innate desire to create, paired with her investment in her community, led to the development of an even bigger project during the same era. Molly partnered with friends and other survivors of sexual assault to create Southpaw, a community space founded under the non-profit Future Economy Collective. Molly talks about a trend in which targets of abuse are often forced to flee, rather than the abusers. “But we were very stubborn,” she says, “and we decided to start our own space.” The volunteer-run site—part-cafe, part-library, part-performance venue, part-grassroots-organizing-polestar for Appalachian Virginia—fills the basement of an unassuming brick office building near Virginia Tech. The refuge, especially during the pandemic, became popular with folks who felt like cast-outs in the small-ish town of Blacksburg, largely high schoolers and grad students looking for community. The group has also organized and raised funds for mutual aid efforts like a community fridge and food box drop offs.

Molly guides me among open boxes strewn across Southpaw’s latest venue, a two-thousand-square-foot basement she’s been renovating since August 2021, while balancing a full-time job as a rent relief program manager for Legal Aid. The cobbled-together space sparkles with odds and ends of art largely from Molly’s imagination, which is energetic and immense, a scattershot of deep intent and pure whimsy. Southpaw hosts a seed library with flashcard-sized drawers for peppers and dried papaya pits and a retrofitted vending machine for pocket-sized poems and colorful pencils that say things like proud parent of a child who passed the vibe check and bitcoin. (“I made them because I was really drunk one night, but now I have so many.”) Posters illustrating past United Auto Worker strikes will eventually adorn the walls.

Molly’s work, both her rugs and the kaleidoscope of Southpaw, follows in the same lane as other Southern absurdists and folk artists who reconstruct their vision through whatever media they have on hand, material that is oftentimes found in nature, in scrap-yards, or at discount stores. They make things for spiritual reasons, out of curiosity, to tickle a rib, or to heed the scratching call to see things differently, to pull the sheen of the known world inside out.

Walks to the Paradise Garden, a book on Southern artists published by the gallery that hosted Molly’s exhibition, describes these artists as “directly involved in making paradise for themselves in the front yard, the back garden, the parlor, the sun porch, the basement.” Jonathan Williams, the book’s original curator, concludes that, “Salvation can come, on one level, from being paid attention to and being recognized.”

"all burner phones crushed in parking lots go to heaven," yarn, monks cloth, and velvet by Molly Z. G. Courtesy Institute 193.

Interrogations of place and community feel like the ideological heart of Molly’s weirdest work, which focuses on Appalachian labor struggles and ecological desecration. In a quilt called manifest destiny, faded square photographs are overlaid onto fabric: shots of pale green pipeline, rust-colored dug-up earth, workers outfitted in hardhats, mountain landscapes that are whole and mountain landscapes that have been torn apart. In the center, Jesus is surrounded by a sun-colored quilt star. He’s wearing a fluorescent construction vest. Molly’s understanding of class conflict and late capitalism, threaded through her art and her work with Southpaw, comes to full effect here, where in the lunacy of mainstream Christian history is laid bare. Laborers are promised an ending of wealth and salvation, if they can just work hard enough.

In the introduction to My Land is Dying by Harry Caudill, Harvard professor Robert Coles writes that extractive resources like coal are so desperately needed by those with wealth, like factory owners and power companies, that they’re obtained as quickly and efficiently as possible—at the expense of exploited laborers and the surrounding environment. “As for those who worry about land being destroyed, water polluted, wildlife killed,” Coles notes with an ironic tone, “they are willful troublemakers, or cranky social critics, or at best they are romantics, hopelessly unable to appreciate the contemporary needs of an ‘advanced’ nation like ours.”

Molly joined the ranks of these romantics on April 30, 2021, six months before their gallery show. That Friday morning, Molly drove a silver Subaru—owned by her father—to a low-slung bridge crossing Brickyard Road in Giles County, Virginia. Molly had driven her passengers to the bridge to protest the construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, a natural gas pipeline that would span 303 miles of Appalachia. Protestors cited grievances like irreparable damage to land and clean water, the folly of fossil fuel investments in the age of climate change, and the three hundred fifty water quality–related violations that had garnered the pipeline owners over two million dollars in penalties across Virginia and West Virginia.

Immediately after Molly’s car arrived, a man named Thomas Adams, a former hydrologist with the National Weather Service and director of the Skyline Soil and Water Conservation District in Montgomery County, got out of another car. Using a black and orange duct-taped lockbox, he lay beneath a flatbed truck loaded with a few rusting sections of pipeline and locked himself to its undercarriage.

Molly had initially planned to leave after her carpooling duties were over; it was finals week in their online Design and Urban Ecology master’s program at Parsons School of Design. But within three minutes, the situation escalated. Pipeline workers moved to block the road and Molly’s car.

When police arrived, Molly says they cooperated with the officers, who took their information and license plate number. Three hours passed. Molly worried about the final waiting at home to be completed. They had to pee. Eventually, officers started a timer for protestors to skedaddle, slowly counting down. But when a police liaison associated with the protestors asked about freeing Molly’s car, Trooper Hackney of Giles County stopped the countdown, arresting Molly, who held a sign that read “No Prisons No Pipelines.” Molly was put in a police car while officers removed Adams from his lock.

Ten days earlier, a protester from Michigan had spent four hours locked to a construction crane in a neighboring Giles County town; about one month earlier, two tree-sitters had been removed from their perches after two and half years of sustained protest in Montgomery County, where Molly lives. All three were charged with misdemeanors. But Molly was charged with a traffic citation for being improperly stopped on a highway, a misdemeanor for obstruction, and two felonies: one for unauthorized use of a vehicle and a second for kidnapping the driver of the truck Adams bound himself to (“abduct by force/intimidation”). According to the Roanoke Times, state police “later learned that a woman had stopped the truck as it was headed down Brickyard Road, which allowed Thomas to attach himself to the rig.” But Molly denies this, claiming she never spoke to the truck driver she was accused of kidnapping, and that no one ever asked her to move her car. For these charges, Molly faced up to twenty years in prison.

Molly heard her charges at the Giles County Police Station. When Molly and Adams were moved to the New River Regional Jail in a van (“There’s no seat belts so you’re fucking loose; you’re rolling around like a water bottle.”), Molly turned to Adams and said, “I need you to use your powers as a real adult to tell my parents I’m not a bad person.” At the time, Molly was just twenty-four.

After only a few days in a cell, where other detainees filtered in and out, Molly felt she was beginning to lose her memory. She decided to archive her hours in precise detail, asking for a pen and carefully smuggling away toilet paper that she then separated into one-ply squares to retrace her incarceration. When connected, these sheets created a vertical timeline that Molly called “Access + Event Map.” On the first sheet, they drew a picture of an intake room where Molly’s log claims they spent eight hours, much like the bare rooms shown on cop shows—an elongated, one-way mirror covered the wall across from where Molly sat. Three plastic chairs surrounded a metal table that squeaked when they touched it. “Doors on both sides can only open at guards request,” Molly wrote on the toilet paper. “Sound of them opening is like a car crash.”

The “Access + Event Map” included events that Molly deemed important or memorable: There is a space for “#3 bailed out” and “request for pads denied.” According to the timeline, Molly arrived in jail on Friday at approximately 4:00 p.m. EST. By Monday they still hadn’t showered or been given a change of clothes. They started to smell like a wet Band-Aid. They talked to their lawyer “FOR THE FIRST TIME,” they wrote, the following Wednesday around 2:00 p.m., noting, “We have two minutes to speak.”

On Thursday morning, Molly was moved from a COVID-19 quarantine cell to a cell block where they could finally talk to new people. When Molly told them they were arrested for kidnapping a truck driver, their cell mates laughed. They can look younger than their years, and after almost a week in jail, they say they looked even smaller, “like a little wimp.”

O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the 2000 Coen brothers film, was playing on a television screen in their cell block. Inspired by Homer’s Odyssey, the Odysseus figure in the film is escaped convict Everett (George Clooney), who seeks to reunite with his seven daughters and his wife, newly remarried during his incarceration. The Coen brothers replace ancient Greece with Depression-era Mississippi and Greek gods with stereotyped Southerners (evangelical preachers, Bible salesmen, Ku Klux Klan members, populist politicians, blues musicians). Throughout the movie, Everett and his two companions are chased by a sheriff meant to represent the devil. Everett often answers the relentlessness of trouble with humor.

Molly had never seen the movie. Closed captioning was too small to read and they didn’t have the earpiece needed to hear it. So another person in their cell stood next to them through the entire film, reading out the subtitles and singing all the songs.

Later that night, after seven days spent in jail, Molly would make their fifteen-thousand-dollar bond through donations.

Almost ten months later, the experience has left Molly paranoid. They have an intense desire, now, to always be recording. They bought a dash cam for their car. While they were once supportive of prison abolition work, they now feel the need in a visceral way.

“It revealed how easy it was for police to create such a dumbfounded narrative, and how it was so easy to remove that you’re human. It can happen in seconds,” Molly says. “It gave me some tiny semblance of how it must feel for people who aren’t white to exist. Even experiencing a single week in jail, which is nothing compared to so many people on earth, was really life-changing.”

Then, after a few minutes of tears, Molly pokes fun at themself in a very endearing way, making us both laugh. It reminds me of Everett.

Molly, still out on bail, had to be cleared by a judge to leave Montgomery County for their gallery opening at Institute 193. Two months later, on December 14, 2021, Molly walked into the Giles County Courthouse at 8:00 a.m. By 8:30 a.m., the time court opened for the day, two rows were filled with Molly’s supporters. After an hour of hearing other people’s traffic citations and a couple of criminal charges, the judge called up Molly’s case. Her lawyer described her plea deal with the state—one hundred fifty hours of community service, a year of probation, a ban from any Mountain Valley Pipeline property, a bar from contacting pipeline workers, and a suspension of a one-year jail sentence.

The Giles County General District Court says there’s no transcript for what semi-retired judge M. Frederick King stated in the case, since recorders aren’t available for traffic and criminal citations. But Molly remembers standing for less than five minutes while King gave a homily on capitalism and its critics. “It was bonkers,” Molly recalled on the phone in early January. “Like some dark rendition of a Parks and Rec episode.”

“His entire speech wasn’t about kidnapping,” they continued. “It was about, ‘This is a product that [the pipeline] is making, and people want to buy it, so why are you getting in the way of people buying these products?’ He said he read a news article about Mountain Valley [Pipeline] going bankrupt and he was like, ‘It’s because of people like you.’”

The plea deal Molly’s lawyer struck means her charges were never cleared. They are still on Molly’s record, and Molly says there’s no statute of limitations for her felonies, which could be brought against her for the rest of her life. “It’s created this weird weight over me,” Molly says. They worry the charges will shadow every conversation with future employers. They wonder if they should leave Blacksburg. “I know that’s what the prosecutors kind of want,” Molly told me over the phone in January 2022, the afternoon before meeting with her probation officer. “They don’t want people like me, who care about the health of the community, in this region. But I have spent so long fighting to be here.”

Still, Molly maintains a very clear vision for their future. They think about it all the time: They want a house next to other houses filled with people who they share a community with, with whom they could maybe raise a child (“I attribute that to watching a lot of Gilmore Girls.”), and they want to have land and grow heritage apples and have a bunch of pawpaw trees and have a space where people can go to rest.

"my voyeur" yarn, monks cloth, and velvet by Molly Z. G. Courtesy Institute 193

Just before I visited Molly, I drove to Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, one of the first communistic utopias in the U.S. The sect, founded by British trouble-maker Mother Ann Lee, who traveled with her followers to New York in 1774, honors shared labor, devoted spiritual practice, a craftsman’s eye for aesthetic beauty, and communal ownership of property. At Pleasant Hill, these practices created enough wealth to adopt more members (the Shakers were celibate) and aid less fortunate neighbors. Their radical creed—the belief in creating heaven on Earth as a means of salvation—reminds me of Molly’s work. The creation of an earthly paradise, free of exploitive labor and the capitalistic worship of techno-progress, is an act of faith.

Lee once told her disciples: “We are the people who turn the world upside down.”

On my last morning in Blacksburg, Molly and I meet at one of their favorite places—Heritage Community Park in the Appalachian foothills surrounding town. They immediately start rattling off new stories: first, about their backyard neighbor (“He owns these giant rabbits the size of small dogs and they’re all named after Yankees baseball players!”), then their affinity for autumn olives (“We can eat the red berries!”).

We look out over the Blue Ridge Mountains lined with dips for rivers and dotted with hay bales, all dry green and crimson and wheaty, and Molly, who grew up in the “Paris of Appalachia,” tells me they didn’t really understand their ties to Appalachian culture until they moved here. Molly tells me they decided to learn about the landscape and its history through an unusual avenue: by studying its scent.

For example, when Molly drives along I-81 North, they know they’re forty-five minutes from their house when the rotten egg odor of hydrogen sulfide from the natural gas company seeps into their car. And when they pass the Radford Army Ammunition Plant and the tinge of plastic-y burning (“almost as if someone has set a grocery bag on fire”) hits their vents, they know they’re nine minutes from their doorstep. Smells can become spectral maps, Molly explains, overlaying cities and communities and cul-de-sacs. In an essay called “Invisible Holler,” Molly writes, “The scents of southwest virginia and appalachia as a whole fold history into the present, telling stories of industries come and gone, of shifts in use of space, of interpretations of time.”

That essay is part of a zine called Value Criterion that Molly made for Almost Heaven :^), perhaps my favorite piece from the exhibition. In twenty pages, Molly subverts the elitism of the scent world by turning it into an underdog story: scent as the most underrated of our five senses. Their descriptions make tangible all kinds of smells, like perfumes, deodorants, cigarettes, towns, nostalgia, Molly’s own body.

According to Molly, a perfume by Byredo called Mojave Ghost smells like: “atmospheric greenhouse, flowers for a first date with a cyborg, clothesline of metal sheeting, if the princess diaries’ genovia was real and ina futuristic state”; a Wood Tip Black & Mild Jazz cigarette, when unlit, smells like “a fruity yankee candle. A cabbage patch doll’s cigarette-inspired chapstick flavor from Dollar General”; Spring Grove, Minnesota, which Molly visited a few years ago, smells like “White heart watermelon, tiny beads of blood forming, the smell of renovation and fresh interior paint, Saint Bernard drool, stalks cooked in a hot car for 4 hours, the idea of running naked through a cornfield.”

I practice writing down my own smells: burnt bark for coffee, cold rose for when I press my hand against my eye, cedar and balsam and fir for the candle labeled just that, and they all feel slapstick, basic, unlearned. If art is an attentive practice, Molly applies this perhaps most thoroughly to the translucent world of smells that trail every aspect of their life. Smells, like rugs and pinball machines and toilet paper timelines, become another subject for memory-making and for sense-making of the world. “Growing up very religious, you have this almost mystical view of the world,” they tell me. “You have more of a sense that the world works in mysterious ways.”

Molly’s art is a freeze-frame of these mysteries, of a person in the first quarter of their life reckoning with all they’ve inherited: here’s land theft, there’s exploited labor, here’s sexism and fear and abuse, there’s our obsession with consumerism, and here’s the fires creating a soup of planetary destruction called the climate crisis. They’re creating a better physical world we can live in right now if we could just recognize the absurdity of the one we already inhabit. The work of building that here—of strong community ties, anti-capitalist cafes, mutual aid networks—continues a tradition of organizing long carried out across the South. Molly’s art embodies what Institute 193 director Ryan Filchak calls the region’s “golden rule,” a Southern invocation toward “caring for our neighbors and the land” as “the best chance for survival, and ultimately, salvation.”

When we return to the parking lot, Molly is again trying to explain her art and the compulsion to create it. As she speaks, Molly’s arms are waving around like the arms in the GIF of the Terminator-inspired overcoat, and behind her is the Subaru from the protest and acres of rolling hills still some what intact. I nod vigorously and smell something in the air. I try to pay attention long enough to name it, something like dried leaves and pond water and the very specific clear cold of a late fall morning. If only I could find away to thread it all together.