Willie Mitchell

The Mastermind of Memphis R&B

By John Lewis

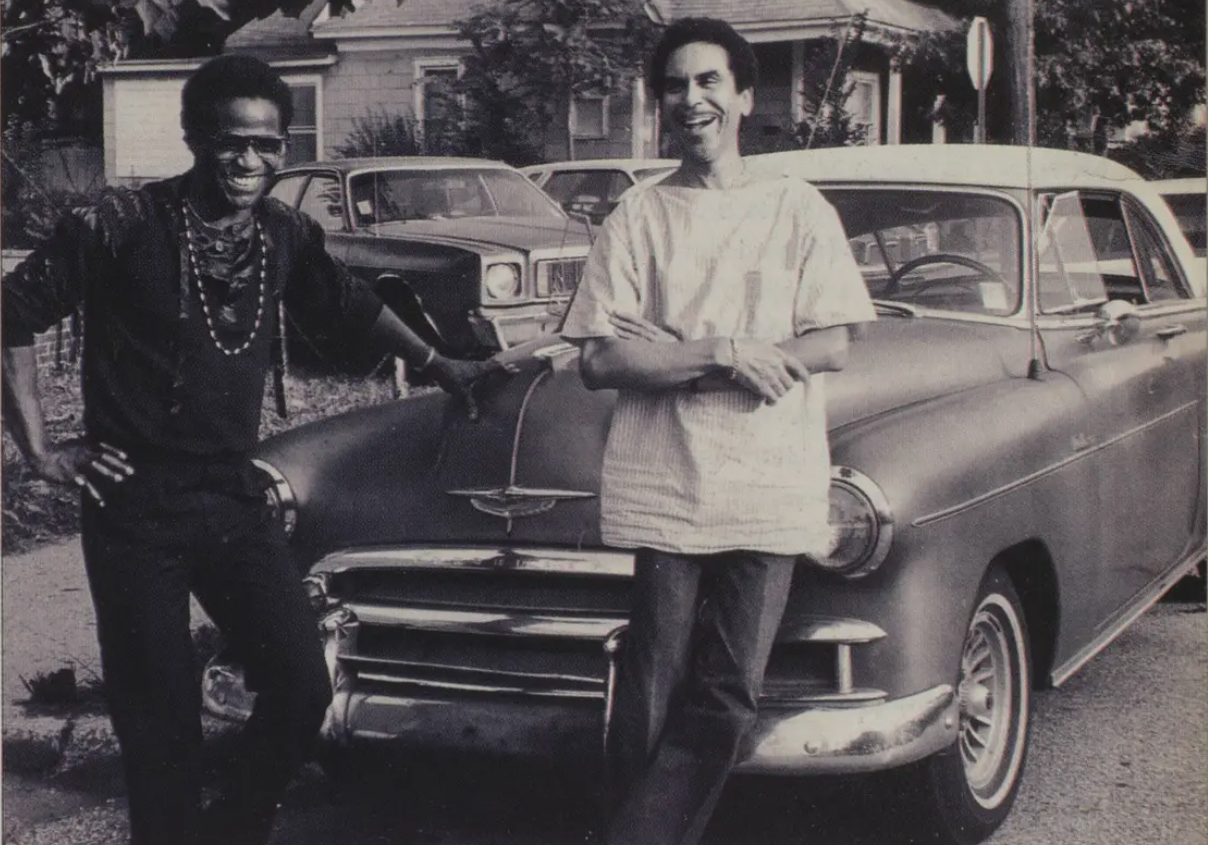

Al Green and “Poppa” Willie Mitchell in front of Hi Studios, 1985, by Patricia Rainer, as featured in the Spring 1997 Issue #16.

Just inside the door at Royal Recording Studio in Memphis, Willie Mitchell sits behind a desk holding an Al Green concert poster a visitor has just presented to him. Studio assistant Floyd Burce, dressed in jeans and a FedEx jacket, and Mitchell’s granddaughter, in a full-length fur coat, sit on vinyl chairs beneath photographs of blond women lounging on mixing consoles. Engineer William Brown, a veteran of the legendary Stax studio (which used to be located around the corner), walks by on his way to the control room. It’s another day at the office for Mitchell, who’s been cutting records at Royal for more than thirty-five years.

Mitchell, the producer of Green’s massive ’70s hit singles, quietly studies the poster, fingers the diamond “W” pendant hanging from a gold chain around his neck, and then tightens the drawstring on his turquoise pants. He exudes wilted elegance. “I got no use for this,” he says, and tosses the poster aside. “I don’t look back. I go forward.”

Mitchell tells Burce to watch the phones and retreats to his office for five minutes before inviting his visitor to follow. Stepping into Mitchell’s office, which is lined with gold records—all Al Green records—is akin, with its orange carpet, drop ceiling, and paneling, to entering some sort of funky time warp, right down to the stereo and turntable. There isn’t a compact disc player in sight. Citations of Achievement from Broadcast Music Inc. and a Billboard Hot 100 Chart for the week ending February 12, 1972 hang on the walls. Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” tops the chart (followed by Don McLean’s “American Pie” [#2], the Carpenters’ “Hurting Each Other” [#6], and the Osmonds’ “Down By the Lazy River” [#7]).

At a desk cluttered with papers and cassettes, Mitchell sits behind a “Poppa Willie Mitchell” nameplate, fidgeting with two packs of More cigarettes and a Barbi Twins lighter. “I don’t believe in all this technology, all these digital machines, and stuff,” he says. “Now, everybody’s goin’ back to analog equipment, but I never made the shift because it took the feelin’ out of the records. Digital puts the top on, destroys the middle, and kills the bottom.

“I been cuttin’ stuff for Chrysalis, Jive, Tommy Boy, Warner Brothers. And everybody wants analog. In the last five months, we’ve done Tom Jones and Boz Scaggs. Bob Dylan’s people have called a couple times, said he might come down and do something with us.”

The artists are no doubt drawn to Royal by Mitchell’s singular production, which is actually more East Coast cool than Memphis blue. Sensual and sophisticated, Mitchell’s work has always been subtler than Stax’s gut-bucket soul and funkier than Motown’s assembly-line pop. Classic tunes by the likes of Green, Ann Peebles, Otis Clay, and Syl Johnson are characterized by Mitchell’s masterful blend of clipped horns, lush strings, and sparse guitar licks all set around silken-smooth, bottom-heavy grooves. For decades, folks have speculated about the source of the warm, resonant throb at the heart of a Willie Mitchell production. Is it the slope of the floor, since Royal is housed in a converted theater? Is it the old equipment? The Memphis humidity? “It’s rigged, man,” says Mitchell, as he fingers his pencil-thin mustache. “It’s souped up like a car.”

When asked how it’s rigged, Mitchell smiles. “I ain’t gonna tell,” he says. “It’s a whole lotta things, and it’s a secret.”

Mitchell is less evasive talking about his musical development, and while many soul men trace their roots directly to the blues, he seems to distance himself from the genre. He neglects mentioning the recent blues projects he’s worked on, such as Preston Shannons Midnight in Memphis and Little Jimmy King’s Soldier of the Blues. “My sound has universal class to it,” he says. “It has a little jazz, rock ’n’ roll, everything in it. It’s what gives my sound another look. It’s not a Muddy Waters, you know, that kind of sound.”

Mitchell credits the Memphis musician Onzie Horn for being the architect of his style. Mitchell was a sixteen-year-old trumpet player when he met Horn, who taught him a method of musical composition developed by Joseph Schillinger, a Russian emigre who counted George Gershwin, Glenn Miller, and Vernon Duke among his students. (In later years, Horn also worked on the Shaft soundtrack with Isaac Hayes.)

Horn took a liking to Mitchell and moved the young musician into his home, a modest house furnished with just a piano and two beds. The teacher and student would play gigs, return home at three o’clock in the morning, and go to the piano, where Horn exposed Mitchell to various chord changes and musical formulas. “I got everything from him,” says Mitchell. “He showed me some formulas, and I’d make my own formulas up. [The Schillinger System] is all about stacking. A chord that had three notes in it, he’d put seven or eight notes in it, but it was still melodic...He turned me on to sounds that were his—he gave them to me, and they became mine.”

In the mid-’50s, Mitchell was gigging regularly at Memphis-area clubs like the Plantation Inn and Danny’s Club. Premier jazz players such as Phineas Newborn, Jr., Charles Lloyd, and George Coleman passed through his band during this period, as did a rhythm section consisting of the bassist Lewis Steinberg and the drummer Al Jackson, Jr., one half of the original Booker T. and the MGs. “I had ’em all,” Mitchell says.

Around that time, Mitchell also began producing records for the Home of the Blues record label. He cut records for the 5 Royales, Roy Brown, and Bobby “Blue” Bland, without much commercial success, and eventually accepted an offer from Hi Records to record as a solo artist. That was in 1961, at a time when Hi was known predominantly for novelty instrumentals such as Bill Black’s “Smokie Part 2.” Over the next fifteen years, Mitchell would become vice president of the label and transform it into a slick, soul powerhouse.

Mitchell says much of Hi’s success was the result of a pair of chance encounters. “One day, I saw this boy playin’ git-tar on Poplar [Avenue] in Germantown,” he recalls. “I’d stopped to get some gas, and he was sittin’ there strokin’ his git-tar. He was about fifteen and didn’t have no shoes on...The notes that was cornin’ out his git-tar had some feelin’ in them. I said, ‘Son, who taught you how to play?’ and he said, ‘My daddy taught me how to play.’ I said, ‘What’s your name?’ and he said, ‘Mabon Hodges.’ I said, ‘You want to learn to play the git-tar?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘I’m gonna carry you home with me.’ ”

“Poppa” did just that. In fact, he legally adopted the young guitarist, who was known as “Teenie,” and groomed him for his band. “I’d go home every night after I got off and teach him three or four chords,” Mitchell recalls. “I taught him to write songs, and I put him in the band when he could play well enough. Then, I put his brother Leroy—tremendous bass player, tremendous—in the band. Then, I put his other brother Charles [a keyboard player] in the band.” With drummer Howard Grimes, the Hodges brothers would make up Mitchell’s renowned house band, the Hi Rhythm Section.

A few years later, Mitchell was playing a club date in Midland, Texas, when a fellow asked if he could sing a few songs to earn bus fare home to Grand Rapids, Michigan. The bandleader agreed, liked what he heard, and, after the show, offered to make the singer a star. “How long will it take?” the singer asked, and when Mitchell said, “Eighteen months,” he replied, “I don’t have that long to wait.” He said he needed $1,500 to pay off some debts, so Mitchell drove the singer to Memphis and gave him the money. No questions asked. And Albert Greene boarded a bus for Michigan and promised to return.

Three months later, Greene came back to Memphis. In short, Mitchell got him an apartment, convinced him to drop the “e” from his last name, and teamed him with the Hi Rhythm Section at Royal. “At first, he sang real hard, like Otis Redding, or Sam & Dave,” recalls Mitchell. “I’d say, ‘Man, you got to sing softer. You can’t scream. You got to float.’ ”

Mitchell’s instincts were on target, and Green’s ethereal falsetto contrasted perfectly with the production’s bottom end. Mitchell’s approach ensured that Green’s vocal pyrotechnics wouldn’t be obscured by intrusive instrumentation, and the pair proved to be a perfect match.

First, they recorded a version of the Beatles’ “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” and Mitchell claims it sold about four hundred copies. “Then, we started gettin’ serious,” he says. “We were cuttin’ ‘I Can’t Get Next To You,’ the Temptations’ song, and I said, ‘Man, let’s do it funky,’ so we done it funky. The thing sold 750,000 [copies], and that was the beginning. The ballgame was on.” Mitchell and Green followed it up with a remarkable string of hits that included “Tired Of Being Alone,” “Let’s Stay Together,” “I’m Still In Love With You,” “You Ought To Be With Me,” “Call Me (Come Back Home),” and “Here I Am (Come and Take Me).” The hits continued into the mid-’70s, when Green entered the ministry and split with Mitchell.

Having achieved such staggering commercial success, Mitchell could have been a hot- shot producer in New York or L.A. Instead, he chose to remain in Memphis, in the same decaying building on South Lauderdale, in the same blighted neighborhood. Floyd Burce reappears, saying it’s supper time and he’ll be ordering food from Ellen’s, the soul food restaurant around the corner. “This is a ghetto,” Mitchell says, “and I love it down here.”

Hearing this, Burce offers an explanation. “If Pop took it uptown, with all the skyscrapers, he’d lose that feel,” he says. “He got to keep that feel.”

“It’s a street thing,” adds Mitchell.

Burce reads aloud Ellen’s menu for the day—meatloaf, hog maws, barbeque beef shoulder, neckbone, fried catfish, fried pork-chops, cabbage, green beans, fried corn, spaghetti, fried and boiled okra, and candied yams. “Any of that sound good?” he asks.

“It all sounds good,” Mitchell says, grinning widely. “It all sounds good.”