Dreadful Hollow

Scenes from an unfilmed and unpublished screenplay

By William Faulkner

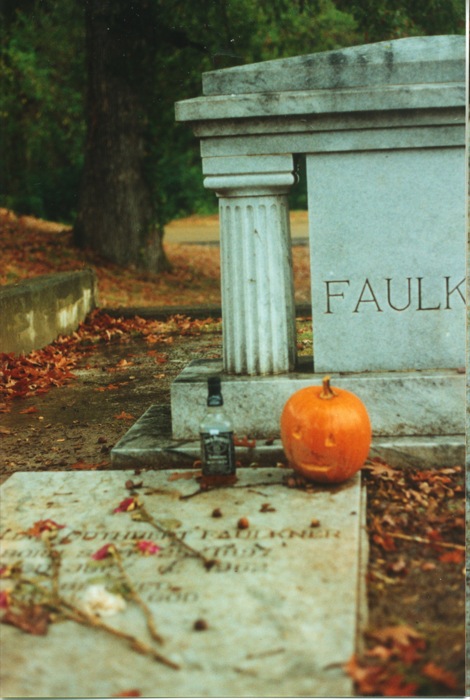

Photo by Gary Bridgman, (c) 2000, courtesy of Melissa Bridgman

“I got mad at him one day and told him I got so sick and tired of the goddamn inbred people he was writing about.”

—The director Howard Hawks recalling a conversation he once had with William Faulkner

Most scholars agree that William Faulkner was unhappy when he was squirreled away writing scripts in Hollywood, as he often was from 1932 to 1954. “They worship death here,” he once said, “They don’t worship money, they worship death.” And: “This is a place that lacks ideas. In Europe they asked me, what did I think? Out here they ask ’Where did you get that hat?’”

It’s probably not that big of a leap to infer that Faulkner’s disparaging attitude toward Hollywood seeped into his screenplay work. Some of the forty-eight scripts that Faulkner wrote were crafty, some of them had their transcendent moments, but most were pedestrian, at least compared with his novels. One screenplay, however, stands out. It is called Dreadful Hollow, and as the scholar Bruce Kawin persuasively argues in his seminal book Faulkner and Film, it is something of a masterpiece. Commissioned in 1945 by Howard Hawks, Dreadful Hollow is noteworthy for another reason: It’s a full-blooded vampire story.

The script was never filmed, but Kawin concludes that “Dreadful Hollow. . .is a brilliant horror film, and reflects an absolute and apparently effortless mastery of the genre. . .[and] could have become one of the period’s greatest and most troubling horror films... Compared to Dreadful Hollow, a film like The Exorcist is both ludicrous and gross.”

The action in Dreadful Hollow centers around a young woman named Jillian Dare who accepts a job as a caretaker at the Grange, a “big, sprawling, grim [house that] is almost a castle.” Meanwhile, young Dr. Clyde steadily begins to realize that he must somehow save Miss Dare from the creepy inhabitants of the Grange.

We could pass along some of what Miss Dare eventually sees in the house—the “dark shape [standing] dimly among the heavy shadows in the corridor” that “swoops” toward her and “seems to have wings, like a tremendous bat, with a pale blur of white for a face”—but that would be getting ahead of ourselves. After all, we are presenting only the first nineteen pages, give or take a few shots, of the 159 pages that make up Dreadful Hollow. We hate to leave you hanging, but... enjoy.

—The Editors

FADE IN

1. INSERT SIGNBOARD TRAIN SOUND OVER

Rotherham Halt London 204 mi (arrow)

Train sound dies away in

LAP DISSOLVE TO

2. EXT. SMALL STATION PLATFORM DAY JILLIAN DARE

—has just gotten off the train. She is about twenty, pretty, in neat inexpensive clothes. She has a bag with her. She faces the Station Master, an oldish man in shirt sleeves and a uniform cap, and two or three yokels. She looks and is shy. She glances about, somewhat at a loss, then speaks with determination to the Station Master.

JILLIAN: I want to go to the Grange, please. Is there a cart of some sort I could hire?

They all stare at her in a curious manner which is a little unusual even for yokels. She notices it.

STATION MASTER: (after a moment) To the Grange?

JILLIAN: Yes. Is there a cart—

OLD YOKEL: A wont let un in, noways.

JILLIAN: What?

OLD YOKEL: T’yellow faced maid wont let’n in t’door, even if Jacob Lee’s let un pass T’gate.

STATION MASTER: Hush, Thomas. (to Jillian) You’m the old lady’s kin, mayhap?

JILLIAN: (shortly) No. Is there a cart or not that will take me and my baggage to the Grange?

STATION MASTER: Bill Waters’ll be going up some evening, when he delivers the groceries.

JILLIAN: How far is it?

STATION MASTER: Matter o’ two mile, follow your nose up the hill yon.

JILLIAN: (takes up suitcase): Will you see that he brings my box up when he comes?

STATION MASTER: Yes miss.

Jillian walks on. The men look after her.

OLD YOKEL: (spits) Furriners.

STATION MASTER: Jacob Lee’s no furriner

OLD YOKEL: Nah. He’s wuss. He’m a loon. Two furriners and a loon. She’m better get back in t’ next train and go back to Lunnon.

3. EXT. ROAD DAY JILLIAN

—walking, carrying her suitcase. The road mounts a hill; there seems to be nothing but hill here. SOUND OF A CAR coming up behind her. She gets out of the road to let it pass. It is a small car, battered. It comes up, slows when the driver sees her, stops beside her. The driver leans out. He is LAWRENCE CLYDE, a young man who looks like a poet, in careless clothes, whose hair needs trimming. His face is intelligent, yet it has a quick reckless look.

CLYDE: Need any help?

JILLIAN: (primly) I don’t think I’ve asked for any help, thank you.

CLYDE: Nonsense, my dear child. Anybody who comes to Little Rotting-off-the-Map needs help. Be sensible, Miss Muffett, and take advantage of Providence.

JILLIAN: My name’s not Muffet.

CLYDE: My mistake. I meant—?

He pauses, giving her a chance to tell her name. Instead, she turns and walks on, carrying the suitcase. He starts the car and follows, driving along beside her in low gear, still leaning out.

CLYDE: Let’s start over then. My name’s Clyde, L. Clyde, L for Lawrence, M.D. for doctor—a harmless would-be poet who is a medico because even poets must eat and so my father, who was a doctor, sent me to medical school, and temporarily the local medico because the incumbent sawbones and gall dispenser is taking a well-earned and deserved sabbatical—

JILLIAN: (stopping) Won’t you please go on?

CLYDE: I was. You’re the one that’s holding us up. Why won’t you ride? It’s three miles to where you’re going.

JILLIAN: It’s only one mile further to where I’m going.

CLYDE: Impossible. There’s nothing between the Halt and Rotherham Village but a mausoleum inhabited by two foreign witches and one local idiot, called the Grange. No young pretty woman is going there.

JILLIAN: I’m going there.

CLYDE: You’re. . .what? (his manner changes completely, becomes sober, incredulous) You’re going to the Grange?

JILLIAN: Yes. Do I have to have the approval of the local doctor?

CLYDE: No. Of course not. Will you tell me why you’re going there?

JILLIAN: To take a position as companion to Madame Czerner, the owner—-if it’s any of your business.

CLYDE: (soberly) I see. (he opens the car door) Get in. It’s more than a mile, and it’s all uphill.

JILLIAN: (hesitates a moment) Thank you. She gets in. The car goes on.

4. EXT. ROAD DAY. THE CAR

—stops before the gates to the Grange. The gates are shabby, in ill repair, need paint; they have a sinister look almost, like those of a prison.

CLYDE: Here we are. Are you still sure this is where you want to go?

Jillian doesn’t answer. She gets out, then turns to take out the suitcase. It is wedged. She tugs at it, struggles with it, Clyde, watching her, makes no move to help.

JILLIAN: (icily) If you’ll be kind enough to help me get my bag out, you can go on wherever you’re going—if you have any where to go.

CLYDE: Of course.

He gets out of the car, comes around to Jillian’s side.

CLYDE: (shoves her almost rudely aside) Get out of the way.

He drags out the suitcase, holds it out. Jillian takes it but he does not release it yet, so that they are both holding to the bag. Jillian tries to draw it free, but he still holds it.

CLYDE: I live in the village—at Doctor Sedley’s house—if you should ever need any.. .assistance—

JILLIAN: (icily, still trying to free the bag) If I ever do, I trust I can find it in the house where I’m to live. (she succeeds in free ing the bag from him) Thank you for the lift.

CLYDE: Not at all.

She goes through the gates. Clyde looks after her. His face is grave, troubled, thoughtful. When she is gone, he gets back into the car and drives away.

5. EXT. LAWN BEFORE GRANGE JILLIAN

—as she enters the gate. She now stands, looking about. The lawn is clipped, well-kept, in contrast to the unpainted gates and forbidding exterior of the entrance. In b.g. is the house—big, sprawling, grim. It is almost a castle. As she stands, a VOICE SHOUTS OFF.

VOICE: Hoy!

She turns. A man is running heavily toward her, waving a pair of gardener’s shears. He has a wild shock of hair, is bent and twisted, looks like an idiot in the face. He hobbles up, glaring at her. He is JACOB LEE.

LEE: Go way! Nobbut aint allowed yere!

JILLIAN: Nonsense. I’m expected. Go back to your work.

He stops, baffled. While he blinks at her stupidly, Jillian passes him and goes on toward the house.

6. EXT. FRONT DOOR TO GRANGE JILLIAN

—crosses the terrace and rings the old-fashioned bell. It BOOMS hollowly in the depths of the house—a deep portentous sound in keeping with the grim exterior. Nothing happens. Jillian is about to ring again, when she starts slightly. A face is looking out at her from around a parted curtain in a window—a grim, harsh woman’s face. The curtain falls back, after a moment the door opens with a slow grinding of heavy bolts and the same woman stands in it. She is SARI. She is gaunt, spare, forbidding, in severe black with a maid’s cap and apron. She has a harsh, yellow face. She gives Jillian a swift up-and-down examination but says nothing.

JILLIAN: The Countess Czerher? I’m Jillian Dare, from London. The Countess engaged me—

SARI: (harshly) I engaged you. My lady does not concern herself with such matters, (she opens the door wider, steps aside) Come in.

Jillian enters.

7. INT. HALL. JILLIAN AND SARI

—It has an air of wealth and decayed splendor, with a faint foreign flavor. Jillian, still carrying the suitcase, looks about curiously. Then she hears the heavy bolts grinding again and looks around to see Sari bolting the door again as if the house were a fortress with an enemy just outside. Sari sees Jillian watching her curiously.

SARI: What are locks and bolts for, if not to use? (she moves on) This way.

She crosses to a door, Jillian following. Sari stops at the door, her hand on the knob.

SARI: Leave your bag here.

Jillian sets the suitcase down. Sari opens the door.

8. INT. DRAWING ROOM COUNTESS CZERNER

—as Sari and Jillian enter. The countess sits in a high-backed chair almost like a throne, close to the hearth on which a fire burns even though it is June. There is something strange about her. At first glance, she appears to be an old woman. But something is wrong. She was beautiful once. She looks frail and wrinkled, her face is lined and the hand which she holds out to the fire looks like a claw. Yet her hair is raven black, her eyes and teeth are those of a young woman. Even her voice is young in pitch, with only a slight crack in it. She stares at Jillian.

The room has the same air of wealth and decayed, ill-kept splendor as the hall.

SARI: The young woman from the London agency, madame. Miss Jillian Dare.

COUNTESS: Come here, child. (Jillian approaches. The countess’ fixed brilliant stare does not waver) Nearer. (Jillian comes nearer as the countess extends her hand. Jillian feels a sudden inexplicable reluctance, but she puts her hand into the countess’. The countess caresses it). So you found your way here. You’re not afraid of being buried alive in this lonely place with two old women? (To Sari, still caressing Jillian’s hand) Don’t deny it, Sari. If I’m old, you are too, you know.

SARI: (curiously short) I’ve not denied it, madame.

COUNTESS: (to Jillian) And you’re not afraid, child?

JILLIAN: (wishing to free her hand, she does now know why) No, madame.

COUNTESS: How old are you?

JILLIAN: Nineteen.

COUNTESS: (caressing her hand) Nineteen. With all life before you. Life. Life. How hungry I was for it at your age!

SARI: (suddenly, moving forward) Likely Miss Dare is hungry for more than that after her long trip. She had better see her room. Perhaps she would like to rest before dinner, (to Jillian, firmly) Come, miss.

COUNTESS: (releases Jillian’s hand, but with a lingering reluctance) Of course, (she turns to the fire, seems to dismiss the whole thing. To Sari) Let her come down to dine with me at seven.

SARI: Yes, madame.

Sari and Jillian cross toward the door. As Jillian is about to exit, she looks back. The countess leans toward the fire, her clawlike hands spread to it as if to draw all the heat possible into the body soon to die. She seems to have forgotten them.

SARI: Come, miss.

They exit.

9. INT. HALL SARI AND JILLIAN

—as Jillian picks up the suitcase.

JILLIAN: Why is she cold in the summer? Is she ill?

SARI: Pray your stars that when you reach her age, fire will be enough to warm you, winter and summer both. Give me the bag.

JILLIAN: I can carry it.

SARI: (harsh, peremptory) Give me the bag.

Jillian gives her the bag. They go on toward the stairs.

10. INT. BEDROOM SARI

—opens the door, enters, Jillian follows. The room is like the rest of the house—big, too big, with the same untended and unused air. Sari crosses and sets the suitcase down at the foot of the bed.

SARI: It’s probably not as neat as you expected. But one pair of hands can only do so much.

JILLIAN: You mean there are no servants in this huge place? Nobody but you?

SARI: And Jacob Lee, the gardener, who enters the house only when summoned.

JILLIAN: I can help you with the housework. I’m stronger than I look.

SARI: You will attend to your duties. I can attend to mine, as I always have.

JILLIAN: I’m sorry. I didn’t mean—But I hope we can be friends, Mrs.—?

SARI: Sari is my name, and I hope I know my place—which is to give respect where respect is due—and deserved. My room is on the floor below, next to madame’s, if you should need anything.

She moves toward the door.

JILLIAN: Thank you.

She waits for Sari to exit. Instead, Sari stops at the door, looks at Jillian for a long moment.

SARI: Why did you take this position? You don’t look like a paid companion. Do you need money this badly?

JILLIAN: (haughtily) Aren’t you exceeding your place a little?

SARI: (makes a contemptuous gesture) I’m old enough to be your grandmother—in my country. Tell me why you come here.

JILLIAN: I need the money. My mother is a widow. I have an invalid sister who must have expensive treatment. But why should I not come here?

SARI: (stares at Jillian, musing almost, as if she had not even heard) If you only were not so pretty—so young—I never wanted it. I was against it from the first. An old woman I said—an old maid—a widow—

JILLIAN: What do you mean?

SARI: Since when haven’t I been sufficient to take care of you? I said. Since you were a slip of a girl, a mere child, lovely as an angel—the two of us together, our lives wrapped up together through all those years, through the radiant summer, into the blackest night—the blackest—black....

Suddenly she pulls herself together, seems to see at last Jillian’s amazement.

SARI: (in the old harsh tone) What does it matter? I’m still here.

She moves quickly to Jillian, grasps her wrist in a grip so hard that Jillian flinches, trying to free her arm from the iron grip. She cannot break it.

SARI: Remember. If my lady begins to fondle and make a fuss over you, you must let me know at once. AT ONCE, do you hear?

JILLIAN: Yes. Let me go.

SARI: (still gripping Jillian’s wrist) At once. (Jillian tugs at her wrist. Sari recovers, releases her) Nonsense. What am I saying? I shall frighten you away.

JILLIAN: (coldly) You won’t need to. In fact, I doubt that you can. You won’t need to be jealous of me. I shall do my duty; no more.

SARI: (calm and cold again) That is well, miss. We will try to make you contented here. Dinner is at seven.

She exits, shuts the door. Jillian stands for a moment longer, puz zled, surprised, a little annoyed yet troubled too. Then she shrugs, gives the matter up as incomprehensible, sets the suit case on a chair and opens it and begins to unpack.

DISSOLVE TO:

14. INT. DINING-ROOM COUNTESS AND JILLIAN

—at the table, Sari serving them. The room is in keeping with the rest of the house. The service is rich, costly in plate, china. The table is loaded with men’s food, far too much of it for a woman, let alone an invalid—rich rare beef, fowls, etc. Jillian, her food almost untasted on her plate, is watching the Countess in amazement. The countess’ plate is loaded; she is eating voraciously, like a stevedore; her plate is filled with cleaned bones. She is holding a piece of meat in her fingers, daintily enough, tearing at it with those sharp white teeth which look so out of place in her old woman’s face. She sees Jillian staring at her. Jillian looks quickly down. But the countess is not concerned. She smiles at Jillian, wipes her lips and hands daintily before she speaks.

COUNTESS: You’re eating nothing, child. Sari, give her some wine. (Sari moves forward, takes up wine bottle)

JILLIAN: I’m not hungry, thank you. I had tea in the train.

Sari fills Jillian’s glass.

COUNTESS: Drink it. We must keep you well and happy—now that destiny has brought you here—you, out of all the million souls who might have answered my advertisement. Don’t you feel that too?

JILLIAN: Yes, madame.

COUNTESS: It is destiny, Jillian Dare. We cannot escape it. We are all flies in that web. It is foolish even to struggle against it. Sari, give Miss Jillian a peach. I love peaches. There is something magnificent about peaches, when one tears out the red dripping heart. The skins too have a downy blush, like your own. She’s really very pretty, Sari—so young, with such pink cheeks and smooth white flesh—

SARI: (suddenly and harshly) You’ve finished, and Miss Dare isn’t hungry. Why don’t you go to the drawing room so I can clear the table? (she approaches, takes the countess’ arm) Come, madame.

For an instant the countess’ and Sari’s eyes clash. Then the countess first looks away. But she covers smoothly, prepares to rise.

COUNTESS: (to Jillian) You see how Sari dominates me. Don’t let her gain the ascendency over you, my dear. (she rises) Your arm, child.

Jillian rises, approaches. The countess takes her arm, leans on it as they walk toward the door.

15. INT. DRAWING ROOM NIGHT COUNTESS AND JILLIAN

The countess goes to the fire, still leaning on Jillians arm, drawing Jillian along with her.

COUNTESS: Ah! The good fire.

She sits in the throne-like chair, still holding Jillian beside her.

COUNTESS: Draw up the stool yonder and sit beside me. You are still young enough to sit gracefully on a footstool. (Jillian draws up the footstool and sits on it. The countess takes her hand again, caresses it) Your English summers. They are cold to me, even with my blood and background.

JILLIAN: You are.. .Hungarian, madame?

COUNTESS: (Caressing Jillian’s hand) From Transylvania. Ours is a very ancient family, our blood the bluest of the blue—except for one tiny drop. But in that single drop is all the fire and fury of a volcano. It is a single drop of black gypsy blood, so that I have also in my veins a legacy from my Tzigane ancestress—a heritage from my country of black forests and wandering tribes, of mountain peaks and wild gypsy music under the stars, and love, and hate—

16. ANOTHER ANGLE. FAVORING SARI

—as she stands in the door, listening.

COUNTESS: But I am old now. That’s why it is good to have you here—young, warm, pretty, with the hot sweet blood of youth in your veins to share with me—make me young again—

She becomes aware that Sari is there, stops. Sari enters. She and the countess stare at each other; again their eyes clash. Jillian sees Sari’s face, rises quickly, alarmed, bewildered. But Sari’s voice is calm.

SARI: Miss Dare is tired. She should go to bed.

COUNTESS: I thought you had the table to clear.

SARI: It can wait. (To Jillian) Come, miss.

COUNTESS: (To Sari) Aren’t you forgetting your place, my good Sari?

SARI: (takes Jillian’s arm. To the Countess) You should be in bed too. Tomorrow—

COUNTESS: Tomorrow! My tomorrows are already older and more certain than all your yesterdays.

SARI: (unruffled, calm) Go to bed, madame. Tomorrow Jacob Lee and I will have a treat for you. (drawing Jillian away) Come, miss.

Jillian obeys. She is still looking at the countess. The countess has changed completely, even while Jillian watched her. She is again a tired old woman who is really glad her guest is leaving.

COUNTESS: Go to bed, child. You are tired. Sleep well.

JILLIAN: Thank you, madame. Goodnight.

But the countess does not even answer. Her clawlike hands are stretched again to the blaze. Jillian and Sari exit.

17. INT. HALL AT JILLIAN’S DOOR JILLIAN AND SARI

—as Jillian, candlestick in hand, opens her door.

SARI: (holds out a key) Here. (Jillian looks at the key) It’s to your door. Lock it before you go to sleep. (looks her surprise) I daresay you noticed Jacob Lee. One is never quite sure of such people.

JILLIAN: I thought you said he entered the house only when he is sent for.

SARI: Sometimes madame is nervous at night and requires him to sleep in the house. Take it. (Jillian takes the key) And one thing more. I will ask you not to disturb anything you find in your room. Please leave it exactly as you find it. Do you understand?

JILLIAN: I’m not even to make my bed in the morning? I can help you that much—

SARI: I am quite capable of all the work here. Goodnight. (she turns)

JILLIAN: Goodnight.

Sari goes on, exits. Jillian looks after her, puzzled. Then she turns and enters her room.

18. INT. JILLIAN’S ROOM JILLIAN

—enters. The bed has been turned down for the night, her negligee is laid out across it. She approaches the bed, still puzzled at this incomprehensible household where she finds kindness and gentleness one minute and rudeness and even threat the next. Then she shrugs this away, starts to take up the negligee, finds the key still in her hand, returns to the door, is about to insert the key when she stops, looking up.

Editor's Note: Faulkner's screenplay is an adaptation of the vampire novel Dreadful Hollow(1942) by Helen Mary Elizabeth Clamp, a prolific author of genre fiction who sometimes wrote gothic novels under the pseudonym Irina Karlova. In 1944, Howard Hawks paid $2,500 for the film rights to the vampire novel, subsequently comissioning Faulkner to write the screen version. This excerpt of that never-produced work originally appeared in Issue 42 of the Oxford American, which was released in the winter of 2002.