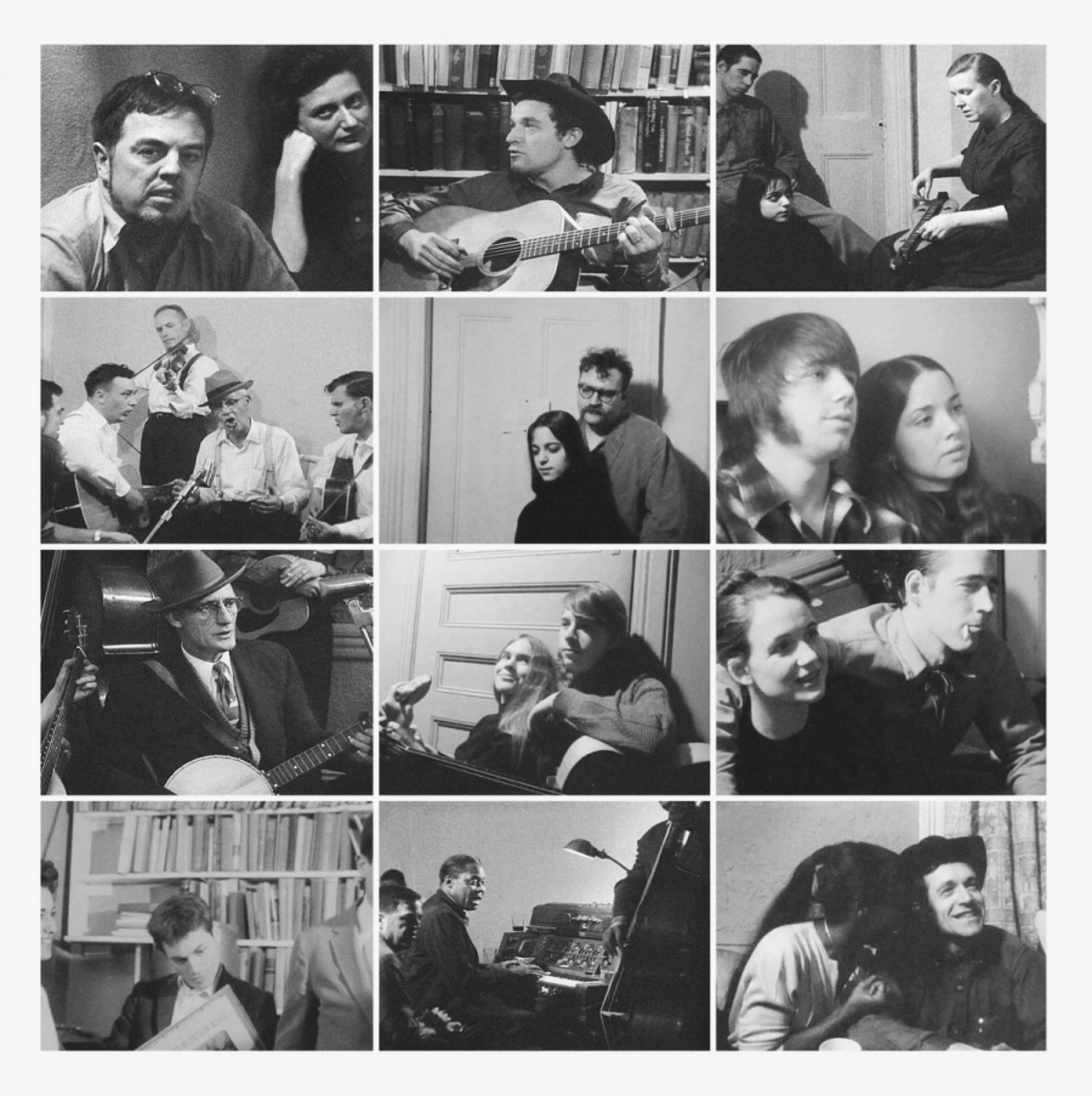

Image stills from the film Ballads, Blues, & Bluegrass (1961; restored and released in 2012). Courtesy of the Alan Lomax Archive

Snacks on Snacks on Snacks

By Amanda Petrusich

Between 1961 and 1965, an organization called Friends of Old Time Music hosted a string of concerts in New York City. This was a period that many consider to be the apogee of the folk music revival, that sweet-faced co-option of rural culture, the scene that birthed Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and a thousand hand-rolled cigarettes. One night, after a show, the writer and folklorist Alan Lomax gamely offered to host an after-party in his bookshelf-lined West Third Street apartment, inviting over a few pals and a cabal of visiting musicians (including the banjoist Roscoe Holcomb, the guitarist Doc Watson, and the singer Clarence Ashley) for “an impromptu song swap.” The ensuing jam is the crux of Ballads, Blues, & Bluegrass, a 35-minute documentary directed by Lomax and recently issued on DVD for the first time by the Alan Lomax Archive.

As a musical document, the film is unimpeachable, and as a cultural one, it’s rife with prizes: Watch Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, a lit cigarette jammed between the strings and a tuning peg of his guitar, seduce a shiny-haired girl in a tartan skirt, rewarding her unyielding attention with a few impish grins (you can practically feel her stomach flip; she is a beating heart in a cashmere sweater). Or, better, witness the bassist and songwriter Willie Dixon nonchalantly define the blues: “The blues ain’t nothin’ but a feeling, when you got a good girl on your mind . . . Music has a way of relaxing your mind against this feeling,” he offers, leaning against Lomax’s organ, drinking from a squat glass of red wine.

Lomax, for his part, circles the room, keeping the camera pointed in pertinent directions. Lomax would have made a goofy reporter and he can be endearingly awkward, as when he corners poor old Roscoe Holcomb, who’s just finished singing, and demands “Where does it hurt you?” Holcomb, a patriarch of Kentucky’s high lonesome sound (and, it turns out, eternally well-mannered), points to his lower throat. Lomax leans forward, a little too close, white-knuckling a microphone stand, and asks him if he’s ever had to cough (“Ever do that?”). I’m also fond of the opening, in which Lomax yanks open his apartment door and a procession of giddy folkies (many with banjos or guitars already slung around their necks, folded copies of the Daily Worker inking the insides of their jacket pockets, lined up like toddlers at a playground slide) trot inside. In the next shot, Lomax, slouching against the doorjamb, wisps of smoke from some unseen source curling around his face, announces “Young people have gone mad over ballads and blues,” and “We’re having a party, so come on in!”

Lomax is a divisive character (there are complicated arguments to be made about cultural imperialism and nationalist pedagogy) but anyone with a pair of functional ears would be hard-pressed to feel anything but grateful for his work. He is singularly responsible for many of the thousands of hours of interviews and field recordings held by the Library of Congress, and he worked tirelessly to collect and preserve strains of vernacular music that might not have endured otherwise. Lomax’s efforts in that vein were preceded, of course, by his father’s, and they inspired the labors of people like Harry Smith, whose Anthology of American Folk Music, released in 1952, became a kind of sacred text for revivalists from Woody Guthrie to Jerry Garcia. What Lomax and his peers accomplished is of historical and archival import, but what is in some ways more compelling is what it inspired and continues to inspire, what people who suddenly have access to Mississippi Fred McDowell’s propulsive grooves, or to polyphonic vocal music from the Mbuti pygmies of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), might do with that information. Folk, as a tradition, is predicated on the open exchange of ideas. Sometimes the results are transcendent; sometimes they are hilarious. The apex (or nadir, depending on your yardstick) of Ballads, Blues, & Bluegrass is the New York folksinger Peter LaFarge’s hammed-up rendition of his own “Ballad of Ira Hayes,” delivered with so much folksy affect even Lomax might have shot him a look. In another place or time, the exchange might result in a British pop singer referencing Jamaican rocksteady, or a Russian rock band incorporating African rhythms. In this way, folk becomes a functional tradition, the seed that sprouts a forest.

Ethnomusicologists have continued to do necessary and significant research, both in the field and beyond, but it’s difficult to muster up a modern analogue for Lomax. No other single figure is as invested in the American musical canon, or as influential. In part that’s the result of a global shift towards self-mythologizing: we all maniacally catalogue and broadcast our lives now, ensuring our legacies to both transcendent and humiliating ends. Who needs Lomax when we have YouTube?

I am reminded (and not for the first time) of “Hot Cheetos & Takis,” a song written and performed by a group of Minneapolis grade-school kids and uploaded last summer to YouTube, where it eventually collected over five million views (Hot Cheetos and Takis, for those unfamiliar with the dusty shelves of urban bodegas, are two aggressively red snack foods coveted by youth). The track is kind of a jam. There are raunchy, Waka Flocka-style beats, enough synthesized strings to provide ample gravitas, and Dame Jones, the group’s presumed leader, explaining what it’s like to be young and hungry in America: “Got like three or four dollars and a couple-odd cents/’Bout to cop me some Hot Cheetos and a Lemonade Brisk.” Be warned, this kid is coming straight for your girlfriend: “Then I walked up to yo’ girl, and she askin’ me to share,” he announces in an early verse. Fault—yours—is clearly implied. Respect is also due to the physically smallest member of the crew, a child of seven or nine who wears a basketball jersey with the number five on it and appears all-too-briefly to wave his little arms around and holler a few frantic, unintelligible demands, like a cross between Mystikal and Animal from the Muppets.

This sort of untempered expression is, I think, precisely what Lomax was after. It indicates the most fruitful kind of cross-contamination (these kids are clearly well-versed in Southern rap, from Juicy J to 2 Chainz) and is uncompromised in the way that only noncommercial (or pre-commercial) music can be. It also came to us pre-preserved, instantly available for all of eternity.

Cultural exchanges like “Hot Cheetos & Takis” unfold online now, rather than in a Greenwich Village apartment or on a porch in Louisiana; the risks are low, but the pathways are more complicated. On the south side of Chicago, drill music, an angry subgenre of hip-hop marked by rudimentary beats and unabashedly violent lyrics, got its street legs on YouTube, where its most beloved progenitor, Chief Keef, routinely clocks in up to 20 million views per video. Drill would not exist, or at least not in the same way, without the Internet. It is repetitive, rough-hewn, unmediated, and visual. Homemade videos (often featuring heavily tattooed, shirtless minors huffing ungodly amounts of weed, stomping around a living room, and periodically brandishing firearms) have supplanted the self-released mixtape as the genre’s preferred delivery system. The videos themselves are approximations, near-parodies of clips released by N.W.A. and the Wu-Tang Clan in the early 1990s, but the songs are infused with a terrifying nihilism that feels all too contemporary. It is a folk music being documented in real time, and it has already become a source material: even before its practitioners started signing to major labels, Chief Keef’s “I Don’t Like” was adopted and remixed by Kanye West.

The Lomax-founded Association for Cultural Equity, which controls his archive, remains in the source material game even now, a decade after his death. Ballads, Blues, & Bluegrass is an official commercial release, but the organization’s YouTube channel, maintained by its young, percipient curator, Nathan Salsburg, proffers a vibrant, sometimes staggering array of footage for aspiring visionaries to mine. Salsburg, like Lomax, has an enviable ear and a populist heart. He understands how (and why) Lomax would have considered YouTube a tool. On one particularly time-leaching morning, I watched nine sequential videos of Othar Turner’s Rising Star Fife & Drum Band marching around Turner’s farm in Gravel Springs, Mississippi, and followed it with a 14-minute performance by the Southern Appalachian Cloggers, shot by Lomax at the Georgia Mountain Fair in 1983. I wish I could say I synthesized these videos into something useful, but mostly I just stared dumbly at my laptop, mouth agape.

Much about Ballads, Blues, & Bluegrass—the idea that music requires an externally appointed keeper, that new and old customs might be exchanged eye-to-eye—seems quaint, and it’s easy to feel nostalgic about a documentary rendered so innocently. Musical revivals are less delineated now; our membranes are too permeable, the past too handy. As the critic Simon Reynolds wrote in his book Retromania, “Each year is better than the last one for music from yesteryear.” Even without an intermediary like Lomax, Soulja Boy’s “Stacks on Stacks on Stacks,” an Auto-Tuned paean to sudden wealth, became a refrain of “snacks on snacks on snacks” for the kids of “Hot Cheetos & Takis.”

Obviously, the machinery is in place for a generation of self-documenting American artists to build their own mythologies and to borrow freely and anonymously from ancient and emerging traditions. And yet: seeing Lomax flit about his apartment, or catching the Tennessee fiddler Fred Price giving the camera side-eye, or watching Mike Seeger of the New Lost City Ramblers shush the room, or hearing Willie Dixon and Memphis Slim lock into some intense, iniquitous rhythm, it’s hard not to feel like something vital, something extramusical, is being communicated here. Flesh on flesh on flesh.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.