Another Country

By Osayi Endolyn

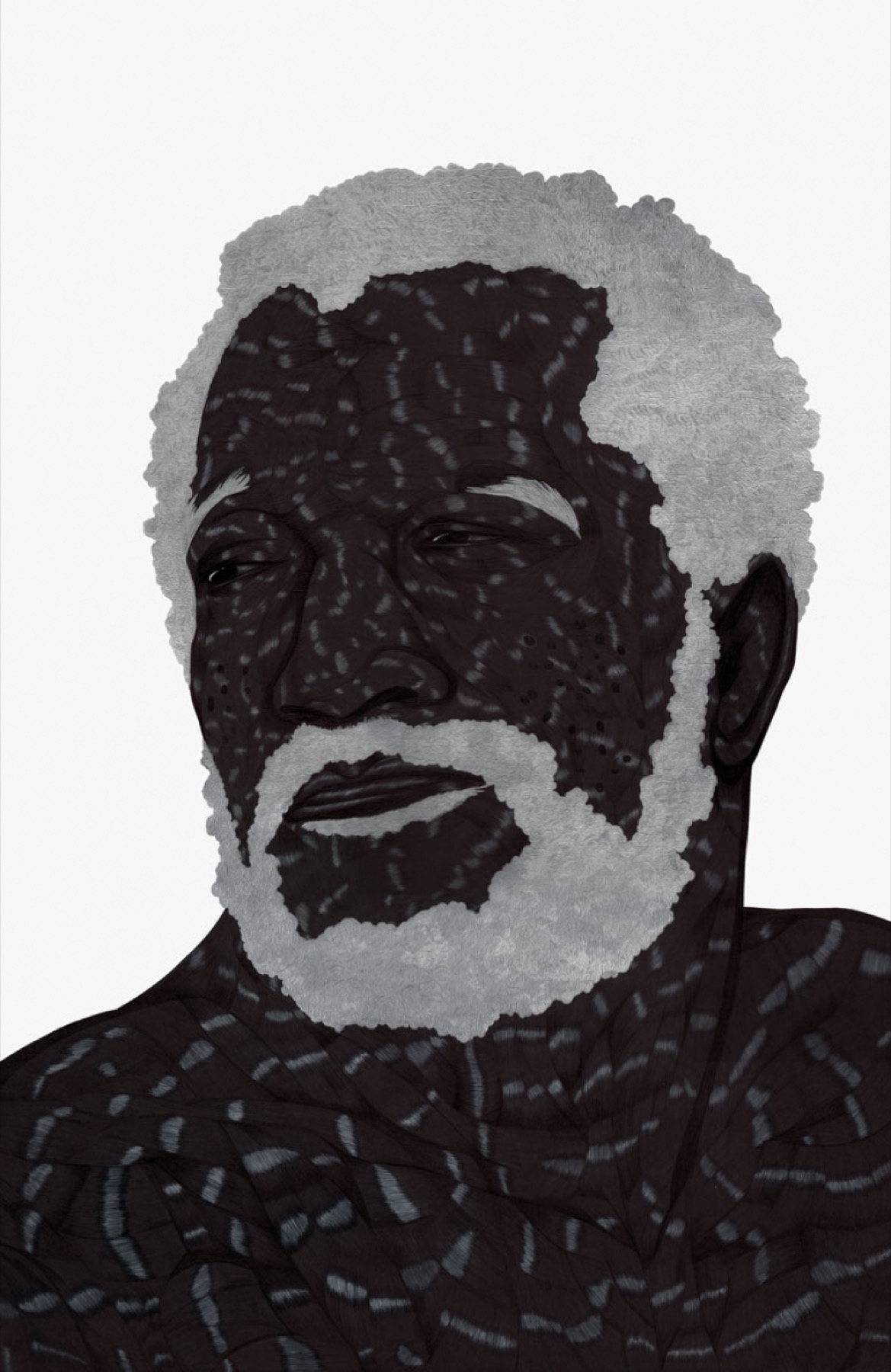

Toyin Ojih Odutola, American (born 1985, Ile-Ife, Nigeria), The Philosopher, 2013–2014, pen ink and marker on board, 30 x 20 inches (sight), 35 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches (framed), signed, titled, and dated on verso. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection: Purchase, Collectors Group Fund. 2015.004. © Toyin Ojih Odutola. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

We were late. The caravan of rickety Toyotas, Fords, and Volkswagens rolled up Enoma Street to my father’s home in Benin City, Nigeria. An uncle in Dublin had described this property as vast and beautiful, worthy of my dad’s “big man” status. I’m not sure what I expected—perhaps paved roads, manicured landscaping, reliable electricity. But Enoma Street turned out to be unpaved and dusty red, littered with tin-roofed shanties and forgotten debris—plastic water bottles, tire remnants. We dipped and swerved past dirt crevices and stopped at Fourteen Enoma Street. The house was indeed the most impressive structure in the viewable vicinity, but it was not a rich man’s home. The wrought-iron gate towered at about eight feet high. Affixed to it, my father’s poster-sized face smiled down on us, the same image from his 1989 doctoral graduation at UC Berkeley that would also grace the laminated funeral programs, commemorative t-shirts, and plastic-wrapped datebooks that could only have been made in China.

The February afternoon air was thick with heat. It was Harmattan season, but the view was clear. Behind us, four pallbearers in matching royal purple dashikis and pants removed the bright white casket adorned with gold-colored grommets from the hearse—my first full view of the box that held my father, dead for more than five months. The men hoisted the container onto their shoulders, marched into the courtyard, and placed Dad on the wobbly desk. Later, I would hear that it was customary for the body to visit its place of burial prior to the church service, but at the time, no one offered us an explanation. We waited silently in the still heat, like our assignment was to sweat.

About twenty minutes later, three musicians arrived: one trumpet player and two drummers—boys who looked fifteen years old. A videographer appeared. The band launched into a loud and brassy tune. Someone opened my father’s casket, and the cameraman zoomed in on his face. I turned away. I’d soon discover that throughout the multiple funereal milestones my father’s Edo culture required, a man with a camera would hover in front of my brother and me, recording our bewilderment, frustration, covert attempts at humor, and grief. Earlier that morning I’d seen my father in the shoddy morgue, alongside other bodies. I now knew how a person could look after below-average embalmment, mediocre refrigeration in a tropical climate, and several months waiting to be buried. I suppose no one looks like themselves upon death. But my father’s body, shriveled and many shades darker, looked like someone else’s.

The casket was then closed, and the group of family members, friends, and onlookers eased back onto the street. The pallbearers carried my father’s casket from the courtyard into the small crowd. “Come, see how we do things in Edo State,” a woman standing nearby said to me.

The ushers danced in unison with impressive, fast-paced footwork, even as my father weighed on their shoulders. The band vamped a series of high-tempo and percussive songs. Goodness, did they dance: family members I didn’t know and well-wishers who were fond of my dad, or at least claimed to be for the sake of his American children. They danced and waved their hands in the air. Naira bills emerged from pocketbooks and purses. The currency, so low in comparison to the U.S. dollar that it meant almost nothing to me, collected at our feet.

I felt a rush of familiarity. For the first time in weeks, something about my father’s death and the ensuing procedures made sense. “Well, damn,” I said aloud and to no one. “It’s a jazz funeral.”

I have been to New Orleans several times, but I have only seen a second line parade once, at Jazz Fest, part of the street performances that take place during the two-weekend affair. A big band glides down the street playing somber music while tourists and locals bring up the rear. Traditionally, the music at a jazz funeral announces the burial ceremony, acknowledges the participants’ grief, and, when the music hits an upward swing, celebrates the life of the deceased. People follow the band in a slow march-dance and wave white handkerchiefs in the air. The event is cathartic to witness and experience, even during the swampy, overcrowded days of the festival. In Benin City on Enoma Street, I was as much a spectator as a participant. I watched my father’s casket undulate in the care of men who hadn’t known him. Middle-aged mamas whom I had never met, but who carried a cultural authority I could never contradict, instructed me on how to stand, when to dance. I almost expected someone to tell me when to look sad.

A kind of connective tissue linked my country’s most African city with an African moment that seemed stunningly American. The pallbearers danced, the band played, the mourners walked and swayed alongside while men and women pressed yet more naira bills on the sweat of our bodies—a symbol of respect and goodwill.

I can make it through this day, I thought. I can make it through this trip. I wondered if my dad had similar thoughts when he visited for his father’s funeral, back in 1989. When he got word of his father’s death, he wailed into the phone of our Bay Area apartment. I was about six years old and, in my cloudy memory, we were home alone. His sobs, “No, no,” over and over again, terrified me. I had never seen my father cry, scream with abandon. He was crouched forward in his seat. I ran to him and placed my hands on his leg. “Daddy?” I asked. But he rose abruptly, phone glued to his ear, and shut himself off in the master bedroom. I know now that part of what he grieved was not being home. I believe he struggled with his choice to build a new life so far away. He’d left Nigeria when he was barely twenty years old. I wondered what it was like for him to return at the impetus of death, his bossy nature amplified by fifteen years in America. I wondered if he was welcomed by his family in Benin City, or if he was confronted by how much he’d changed; how others had changed. Could he navigate the customs with ease or had he misremembered? What had home become, if not another place to prove himself?

“I’m in Athens,” my father said over the phone. He sounded weak but happy to be talking to me. “I’m with my parents. I want you to come meet them.” It was August 2014. My father had not told me he’d be near Atlanta, where I lived then. This was typical. The twelve-hour transatlantic flight from Lagos is hardly a last-minute decision, but he was the kind of man who deemed other people’s planning irrelevant.

“Your parents?” I asked, wondering who he could be referencing. His mother passed in 2010.

“My Christian parents!” he rejoiced. “They helped me come to this country.”

This country. My father had arrived in San Diego, California, in 1974 as a university student. He lived in the state as a permanent resident, married an American, had American children, and only moved back to West Africa in 2009. During that thirty-five-year period, he visited his homeland a handful of times, by my count. Yet the United States was still “this country,” his accent, at times, difficult for me to decipher despite his impeccable, authoritative command of English. His “Christian parents”—I’ll call them the Smiths—were a white American couple who met and befriended my father through their Southern Baptist church in San Diego.

I was reluctant to make the one-hour drive to Athens. Years ago, I had forgiven my father for his often cruel parenting. He ruled by the fist. Spurred on by a culture that sees children as ancillary to elders, and encouraged by an unstable personality that eluded medical diagnosis, my father had become wholly unlikable by the time I was a teenager. The pain of my childhood was in the past, except that he always came to our intermittent meetings with strings attached. I would set boundaries, but he paid no mind. I demurred and we hung up. A day or so later, I received a call from Mrs. Smith.

“Darlin’, your father is unwell,” she said. Her drawl was urgent, but kind. “You should come. Come see him.” Born and raised in California, I had lived in the South long enough to feel bad saying no to an old lady. Especially one who had an indirect but meaningful impact on my very existence. I had been summoned. So, I went.

By that time, Dad had suffered multiple strokes, one major and many minor. He held a postgraduate degree in public health, had taught at Cal State University, Fresno—distinctions not apparent in his role as patient. He ignored doctors’ advice, skipped prescriptions. His medical care was a patchwork of appointments during rare visits to the United States. When I saw him in the Smiths’ living room, he seemed to have shrunk. The left side of his face drooped and his left arm hung at a bent angle, revealing its limited mobility. His eyes appeared jaundiced. I was shocked by his decline.

My boyfriend accompanied me to Athens, and we shifted awkwardly on the sofa while Mrs. Smith fetched snacks. She chastised my father, who was sixty years old, about taking better care of himself. He giggled as they bantered back and forth, no time lost between them. The scene left me with amusement and distaste: here was my AARP-approved dad, fragile yet still surely manipulative, enjoying the maternal care of an elderly woman who ought to have had someone taking care of her. He felt totally at ease, right at home despite never having lived at that address.

“Mummy,” he called to her from the den. “Please, may I have some more tea?”

I asked my dad, Why not move back to California? He could be closer to his young sons from his second marriage. He mumbled an off-color comment about his soon-to-be ex-wife and said he enjoyed his work as dean at William V.S. Tubman University in Maryland County, Liberia. He’d been hired to launch their public health program. I said nothing. Maybe my half brothers, boys I’d never met in person, were better off with Dad at a distance. Then, he added, his lips dry and ashen, “Anyway, I don’t want to die in this country.”

That was our last face-to-face visit. Two years and one month later, Labor Day 2016, my father died at his home on Enoma Street, after years of hypertension and heart disease. He was sixty-two.

On my mother’s side—people who did not immigrate, but were descended from those who were stolen—my family talks of the old days in Mississippi and Louisiana, when white landowners, the boss men and women, died. Grief-stricken, white family members would find the senior members of a trusted black family—maybe the black preacher’s family, or folks who worked the land. Somebody who was “representative.” Black folks were called to stand witness at the departed white person’s bedside because, as an elder cousin put it to me recently, “they always thought we were closer to God.” The white families wanted the black people to pray, or sing, to provide comfort en route to whatever waited.

Such stories, told about my great-grandfather and those before him, make this side of my family, children of the Great Migration, chuckle knowingly. From the days of Negro spirituals to today’s r&b runs, black people have been ascribed a universal earthiness that is both salve and sword. The assumption can be comforting to those who embrace a lineage of survivors who created beauty out of incomprehensible trauma. But the assumption can be wounding when others misinterpret the deep, soul-searching echoes of black prayer and black music as mere entertainment. Though I am separated from those ancestors by decades and lifetimes, we share the experience of being called upon for our blackness in rooms full of white people.

That, in part, is why black funerals in America are so meaningful. Black funerals weren’t just farewells to the dead—so often, during my great-grandparents’ time, victims of racial violence sanctioned by mobs or the state. Black funerals could be unapologetically, culturally black, even when families lived under threat of imminent danger. Congregating, a crime for groups of African Americans in many Southern counties, could be tolerated for an afternoon. Funerals, or homegoings, fancied that the deceased had gotten the reprieve he or she rightfully deserved. Their spirit was on its way back home.

Then and now, the day of a black funeral can be a celebratory, though grief-tinged, event, even if during enslavement such praise was shared in secret. People got in death what they couldn’t get in life. For many, that meant a heartfelt hymn, sung in private, away from the glare of overseers. For others, decades later, that meant horse-drawn carriages for domestic workers, or lavish bands for farmers. Black funeral tradition acknowledged that the world might not have treated you right. People were going to enact laws to render you inhuman, erect statues to remind you of that era then sell it as “heritage,” and embed the supposed inferiority of your blackness for generations in everything from land zoning to hair products to music publishing rights. But, black tradition said, your people, dogged as the day is long, survivors of the long, good fight, were going to see you off in style.

So I was not totally surprised, back in October 2016, when my father’s eldest sister, Helen, called from Benin City to inform me that the Edo burial tradition required that my father’s funeral take seven days. Of course, I thought, of course, the black funeral tradition came, in part, from this precursor. Helen said that as the eldest child, I had certain responsibilities to manage, such as the food, the casket, and the cost. I thought about the years my father lashed out at me, my younger brothers, my mother. I thought about the years he was absent following my parents’ divorce, except to remind me whose daughter I was. I remembered his gregarious laugh, his stunning smile, his flawless suits, his bow ties in springtime. I remembered the “food from home” he cooked for us that I still craved. I remembered how he’d spontaneously dance with us and playfully recast songs. A constant favorite was Bob Marley’s “Running Away.” “You can’t run away from yourseeeelf,” he’d sing a cappella, shaking his head with his eyes closed. I remembered how he could be doting in public view, then knock me across the room once guests left, and sometimes beforehand, for unknowable offenses. Seven fucking days. I laughed.

For a man who was constantly late, my father hated to be kept waiting. I could not stop thinking about this, first in Lagos, then in Benin City. Everything was behind schedule. My father’s funeral was originally scheduled for November, the soonest we could travel, given work schedules and the herculean difficulty of acquiring visas from the Nigerian consulate. But in late October, almost two months after my father’s death, Helen called with an update. “The Oba has died,” she said, her words slow and crisp with finality. “There is a moratorium on funerals until January due to the new Oba’s coronation.”

I didn’t know how to respond. I could not understand how the death of one person had enough relevance to cancel every pending burial in the state. We had booked our flights, received our multiple immunizations. Yellow fever alone cost me $200. I was ready for closure, to end the parade of calls and texts from all over the world, so-called family emerging from nooks and crannies to say sentimental things about my dad.

“Can we talk to the Oba?” I asked.

“You are not understanding,” Helen said. She was amused, but wistful. All those years my father spent in the States, he failed to teach us so much. The Oba is a traditional monarch figure dating back thousands of years, all reportedly from the same paternal line. Bini people, the descendants of the old Benin empire, still honor this figure despite Nigeria’s democratic infrastructure. The Oba, like most kings, is seen by followers as an extension of God. He has palatial housing and many wives. In other words: He’s not a guy who takes pleading phone calls. Websites had reported the previous Oba’s death back in April, but the coronation activities were not announced until the fall. Which is how we came to bury my father in February 2017, as part of the three-day ceremony I had negotiated with his family—with my family. Three was manageable. Seven was not. I said I’d split the cost.

This was day one. Day two would be the thanksgiving ceremony with music and dance. Day three would be another church service. But on this day, the first day, I just wanted to bury the man. Our caravan arrived at a church on King’s Square. A minister with Malcolm X–style glasses tapped his watch at Esther, who apologized for our tardiness. The congregation settled and the service proceeded. I had been asked to read an obituary that touched on the facts of his life, which I did without fanfare. A tone-deaf choir sang every verse of “Amazing Grace” at a speed so glacial that the Pope would have fallen asleep. Another minister led a generic sermon about Abraham.

Upon our return to Enoma Street for the interment, casket in tow, the gravediggers were still not done, so we waited. I joked with my brother about the delay, “It’s not like they didn’t have enough time.” For this waiting period, we had chairs, but I learned on that day that chairs for next-of-kin can be traps. We sat while men and women who knew our father, some of whom remembered me as a visiting toddler more than thirty years ago, greeted us. In the months following my father’s death, I had heard how many loved him. He had paid for people’s schooling and contributed to others’ medical bills while his own children took out student loans. He had helped young immigrants adjust to life in the States while his kids passed months without a guiding word. Others let their succinctness speak volumes. “I knew your father,” they’d say. “So sorry for your loss.”

When the grave was ready, my brother, my boyfriend, and I stood adjacent to the hole in the ground. I held my brother’s hand as the minister led a prayer and the attendants lowered my father’s white casket into the burnt-orange dirt. The cameraman walked toward us, then leaned in, framing our downcast faces from mere inches away.

Esther stood behind us, gripping our shoulders. She moaned and cried. “Talk to him,” she heaved. “You can talk to him.” I didn’t want to talk to my father. We’d said everything. The gravediggers pushed the dirt mounds on top of his casket, and I watched as people tried to pull us away. I wanted to see.

My whole life, a current of anger pumped through my father. He seemed angry that he’d left Nigeria, angry that he’d stayed in California, angry that his home wasn’t what he remembered, angry that global forces exploited and destabilized his homeland, angry that in California he was black and not Edo, angry that his kids were more American than African, angry that America had changed him, too. I wanted to see, even as my eyes blurred with quiet, resolved tears. The dirt piled on and I felt the lightness of relief. He was home. No more running.

Thank you, I said to him silently. I know you tried. I’d come a long way without him, in spite of him. But he was my father. And now he was gone.

I watched and watched, until the last white corner of his casket vanished under a damp clump of dirt.