Writing Motherhood in Arkansas and the Missouri Ozarks

Authors Jennifer Case and Bailey Gaylin Moore in conversation

By Jennifer Case

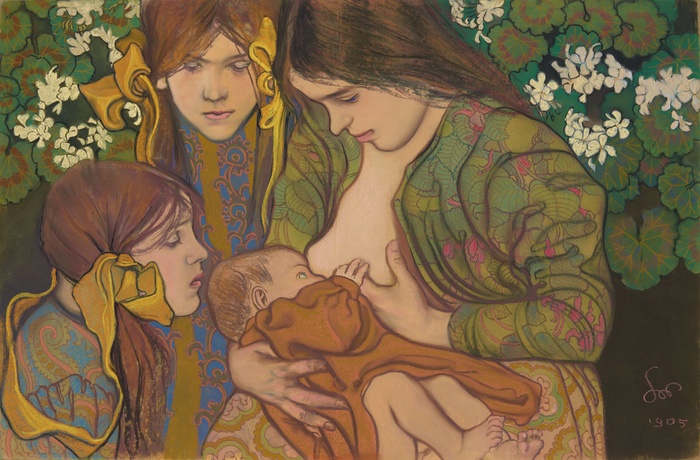

Motherhood, 1905 by Stanisław Wyspiański, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bailey Gaylin Moore and I both started writing about motherhood around the same time—Moore from the Missouri Ozarks, where she’d grown up, and me from central Arkansas, where I’d moved almost a decade ago. Bailey Gaylin Moore’s resulting debut essay collection, Thank You for Staying with Me, was published this month as part of the University of Nebraska Press’s American Lives Series, while my own book, We Are Animals: On the Nature and Politics of Motherhood, was released last fall from Trinity University Press.

Although Moore’s collection of micro-essays explores more than just motherhood—touching on astronomy, mother-daughter relationships, ontology, and the lingering effects of sexual assault—we quickly discovered that our books were working in tandem to expand literature about motherhood in the South. Both books address the emotional and political complexities of unintended pregnancies in conservative regions, as well as the isolation and maternal health barriers many mothers face.

Recently, we corresponded via email about place-based writing, stories about motherhood in Southern literature, and current issues surrounding reproductive healthcare in the South.

Jennie: I was so excited to hear about your book, since you were writing about motherhood and life in the Missouri Ozarks, just a few hours north of where I am in central Arkansas. Having recently published a book of my own about motherhood in Arkansas, I knew I needed to read it. In addition, my grandparents used to live near Joplin and then Springfield, so I have a lot of memories of that region. Can you talk about your book in terms of place-based literature?

Bailey: I love hearing about your connection to this region—it’s always meaningful to talk with someone who knows these landscapes intimately. Thank You for Staying with Me is rooted in Missouri, not just as a backdrop but as something very much alive. Writing about place isn’t just about setting, it’s about tracing how a landscape lingers in the body, how it shapes the way we move through the world. The Ozarks is paradoxical—beautiful yet isolating, carrying deep-rooted traditions while holding the desire to carve out something new. It’s a place that holds you close but also reminds you of what can’t be held at all. I wanted to capture that push and pull, how the land both anchors and unsettles.

Jennie: In “The End of the Rainbow,” you describe the anti-abortion billboards that line southern Missouri highways and your visit to the Pregnancy Care Center, a conservative counter to Planned Parenthood that later used your story to glorify its pro-life efforts. The language of this essay felt so familiar to me. What did you most want your book to convey about the conversations surrounding reproduction in the Ozarks?

Bailey: At seventeen, I didn’t have the language for what I was feeling, but I knew enough to sigh at those billboards, telling me what kind of mother I should be before I even knew who I was. I wanted to show how deeply those messages shape us—not just through policy, but through the quiet ways they make us doubt our own choices. The Pregnancy Care Center promised support but used my story for its own agenda. I wanted to push back against those narratives and complicate the idea of choice in a place where it’s so often reduced to right or wrong.

Jennie: When I was working on We Are Animals, I likewise wanted to complicate the polarized perspectives people tend to have about reproductive justice and motherhood—right vs left, conservative vs progressive—in part because the stories I saw around me, and that I experienced myself, didn’t fit neatly into a single narrative. I saw this throughout your book as well. There’s a deep love for the Missouri Ozarks, as well as a sadness and grief for parts of the culture. In our very divided world, what work do you hope this collection might do?

Bailey: My biggest hope is that readers—whatever their beliefs—see themselves in the text and feel less alone than when they started.

Jennie: Can you speak a little more about aloneness for low-income mothers in rural regions? A recent report on the maternal health crisis in Arkansas highlighted this demographic, and I noticed how well you captured the experience in “Gal-vanized.”

Bailey: I wanted to highlight the complexities of rural motherhood and the overlooked struggles tied to poverty. These challenges aren’t just medical—they’re systemic, worsened by dwindling resources. “Gal-vinized” takes place after the overturn of Roe, when Missouri was the first state to ban abortion. Sixteen years had passed since I’d even considered abortion. The political landscape was more purple then, with social services that made surviving manageable. Since then, Missouri has slashed Medicaid, WIC, and food stamps. These stories reflect systemic failures. Like you wrote in We Are Animals, motherhood is layered with isolation. It’s crucial to share these stories to better understand the intersections of poverty, geography, and health—and to advocate for change.

Jennie: When we are thinking about the literature of the Ozarks—and by women—who did you look to as models?

Bailey: Every time I think about Ozarks literature, I also think about Daniel Woodrell and the Netflix series, Ozark. My home is often portrayed through caricatures—meth-addled towns, hillbilly stereotypes, Southern Baptist extravaganzas. I felt compelled to write this book to create a fuller picture of its landscape and people, for the women who were quiet heroes, like my seventh-grade English teacher, who always offered hope, even when I visited her after school my junior year and she asked if I was pregnant within minutes. Or Roberta and Judy, neighbors who walked with my mom during her divorce, holding her hand. Janice and Jolene from church, who giggled with my mom in the choir and still sat with me after the pastor made me write an apology letter to the congregation for my pregnancy. My mother, who taught me to be unapologetically female in a male-dominated world. Ozarks literature often leaves me feeling outside of something unfamiliar.

Motherhood by Anna Pasternak, 2005, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jennie: There are some distinct differences between our experiences. You were a single, teen mother who had grown up in the Ozarks, while I had transplanted to Arkansas and was middle class and married. Yet I kept noticing parallels between our books. We both experienced an unintended pregnancy and felt, as you write in one essay, that we “didn’t possess the autonomy to make a choice.” Both of our books also touch on the 2016 election, the last days of Roe, and more. I could feel a very familiar tension beneath the surfaces of many of these essays, and it reminded me of my own struggle in We Are Animals to capture the emotional complexity of an unintended pregnancy alongside the deep love for one’s child. Writer to writer, what was most challenging for you when crafting these tensions?

Bailey: It’s striking how different experiences can still echo each other. One of my biggest challenges was holding space for contradiction—capturing the complexity of an unintended pregnancy without reducing it to either regret or gratitude. Culturally, we don’t make much room for those layered emotions, especially around motherhood. We expect neat narratives. But the truth is messier. I wanted to write into that mess, to show how agency and constraint, joy and resentment can coexist. Finding the right balance—the right moments to let the tension remain unresolved—was the hardest part. But it was also the most necessary.

Jennie: I agree completely. So much of We Are Animals was me writing into that mess as well. Trying to bring the complexities and contradictions of motherhood to light without resolving the tensions, because sometimes the tensions simply can’t be resolved.

Bailey: Yes, and turning to We Are Animals, there actually were moments when I had to pause and pace myself, overwhelmed by your raw honesty about the uncertainties of motherhood. I saw myself reflected in the speaker in “On Contemplating a Second Child,” where you explore the deep ambivalence many feel about expanding their families. How does that ambivalence surface in We Are Animals? And do you think our culture adequately acknowledges this uncertainty?

Jennie: So many women I know have felt ambivalent at points as mothers (or while contemplating motherhood)—and they have also often felt ashamed of their ambivalence. Myself included. One of my main goals in We Are Animals was to make space for those complicated emotions, letting them become part of the literature of motherhood. I didn’t feel I had space for those emotions when I was experiencing them, and I certainly didn’t see them reflected in contemporary nonfiction about motherhood. I wanted to change that.

Bailey: Piggybacking off the theme of our more uncomfortable truths, were there any parts of the book that you struggled to write, either emotionally or structurally? How did you work through those challenges?

Jennie: The hardest essay to write was “To Hatch Intimacy from Despair,” which explores prenatal depression. The essay required revisiting some particularly difficult memories. As a writer, I wanted to honor the intensity of those experiences, but I knew such intensity could also overwhelm readers (and myself). As a result, I drafted that essay slowly, giving myself space between writing sessions to let the emotions settle, and time to gain perspective on the essay’s pacing and structure.

Bailey: Missouri and Arkansas both rank among the worst states for women’s health, yet the conversation is often overlooked. What I appreciated most about our two collections is how we both felt compelled to write about this topic despite having completely different experiences of motherhood. Given how often maternal health is sidelined in public discourse, what role do you think literature plays in bringing these issues to light?

Jennie: When I first started writing about motherhood, I came across a quote by Sarah Menkedick in the Los Angeles Times, where she discussed her initial tendency to “apologize” for writing about motherhood. “Patriarchal culture,” she observed, “has reduced motherhood to an exercise no serious artist would tackle as a subject.” I took it as a challenge and vowed to write seriously and artistically about maternal health. In doing so, I—like you—wanted to validate other women’s experiences and show that women’s reactions (and fears, frustrations, anxieties) were in fact normal, and just as worthy as any other writing subject. More broadly: I do believe literature can have an impact on society and, in this case, on how we approach maternal health. Books can shine a light on where we are failing people, and they can bolster individuals and communities who eventually will work to create change. I don’t know what is going to happen in either of our states over the next few years, but I do know literature can help correct incomplete narratives. I hope both of our books do that work.

Bailey: There’s a deep ontological thread throughout your essays of mothers lacking autonomy—moments when the speaker says, “This is not who I am,” or no longer recognizes her own body in the mirror. At the same time, the book opens with a meditation on maternal power: “You are power, though you do not always know it. You are sparks and mirror neurons and a life force throbbing to reach the future.” Can you talk more about this tension between female empowerment and the societal demands of parenting? On the surface, these ideas seem to clash, but together they reveal a more nuanced theme—the dissonance of motherhood.

Jennie: To me, the entire book is a meditation on control. When is it empowering to give up control, and let our bodies be what they are? And when is it better to retain control, and to resist the forces trying to wrest control from us? The differences between those two aren’t always clear, especially when it comes to motherhood and childbirth. I wanted to parse through those differences in the hopes of finding discernment.

Bailey: In “Birth Work in the Bible Belt,” you describe the subtle yet powerful ways medical professionals exert control over pregnant patients. Your essay captures how fear, power dynamics, and cultural expectations shape the birthing experience, particularly in the South. That tension—between trusting the system and recognizing its failures—felt deeply familiar to me. What did you most want this piece to reveal about the realities of giving birth in a region where religious and political beliefs so often dictate reproductive care?

Jennie: I wanted to show just how ubiquitous that political and religious messaging is in the South. Even my non-religious hospital had religious material in the waiting room, and both my OBGYN and doula practiced through overtly Christian lenses. For those of us who question religious impositions on reproductive care, this was unsettling. Nonetheless, there’s a lot of advocacy taking place in the South, including by women who may not call themselves feminists. I wanted to honor that advocacy, as well as that messiness.

Book covers courtesy of Trinity University Press and University of Nebraska Press

Bailey: Throughout We Are Animals, you evoke a deep sense of geographical loneliness that often accompanies motherhood in less urban landscapes. In regions like Arkansas, where isolation can intensify the challenges of parenting, how do you see geographical loneliness shaping the maternal experience, and what do you hope your narrative reveals about finding connection amidst that isolation?

Jennie: My own geographical loneliness as a mother initially stemmed from my career. I moved often enough, especially early in my career, that I simply didn’t have the support system I needed in place. And yet, rural communities around the US are losing maternal support. So many women in rural regions have to travel hours to prenatal appointments, let alone a hospital equipped for childbirth. I luckily had access to prenatal care where I lived, but I touch on both types of loneliness in the book. Much of We Are Animals engages evolutionary biology, discussing how, in our human past, mothers were never expected to raise young in such isolating environments. I’m passionate about this. So many mothers struggle with isolation—and sometimes judge themselves for it—when the truth is: we were never supposed to “mother” this way.

Bailey: If you could travel back in time, what’s the most important thing you’d want to tell a newly pregnant Jennifer Case?

Jennie: What a great final question! I’d tell her to stop blaming herself. That the tensions she was feeling were societal issues, not individual. And you? What would you tell your younger self?

Bailey: I’ve been thinking about this question a lot lately with the book coming out. I’d let her know that she won’t always feel so alone, so unequipped to navigate the world. In revisiting these past selves, I’ve learned that they possessed an edge and bravery that I sometimes neglect, that they can teach me just as much as I can teach them.