Acts of Happiness

By Osayi Endolyn

Geraud Pfeiffer via Pexels

Black liberation—as a term—didn’t exist in my household growing up, but looking back, I realize we talked about it all the time. An expansive range of Black identity and history was accessible to me through my parents’ LPs and cassettes. Distributed throughout the house was a collection of sculptures my Nigerian dad imported from throughout West Africa, and a teeming bookshelf featured authors like Alex Haley and Angela Davis. To know me and the family dynamics from which I come is to understand that while I was not permitted to watch the decades-running animated sitcom The Simpsons, a show that my parents disliked for its regrettable, white-centric presentation of children disrespecting their parents and causing shameful mayhem, they had no issue with me watching In Living Color, a groundbreaking, risqué sketch-comedy that was decisively more explicit, but centered Black culture and experiences, even as it aimed to be universally, and hilariously, offensive. We watched it as a family. I was as interested in the show’s contents as much as I was in seeing when my parents laughed. Over these years, I absorbed that our at-home, Black culture was different from that of my mostly white public school and the media and entertainment they consumed. My friends in Black households didn’t “talk back” to elders the way my white friends did. When my father’s Edo community gathered, children ate the same foods as the adults; there was no such thing as a “kid friendly” menu. While I did endure hair relaxer treatments at times (an essay for another day), standards of beauty were generally intended to accentuate our natural features. I learned that to be Black and feel free was to create a respite from “out there.” A place where white children and their parents didn’t feel entitled to touching my hair, asking me (as opposed to my father) to explain from where my dad came, always interrogating and inquiring instead of presuming another’s baseline was also normal and mainstream, somewhere. It meant cultivating space for joy in the face of near-constant televised injustices, to laugh and embrace one another even as systemically unfair odds raged on.

The story of Juneteenth, a summer holiday tied to the emancipation of slavery in the United States, is an exceptional tale of delayed freedom, and yet the historic moment was not on my radar as an annual celebration until a few years ago. After leaving the East Bay and before we headed down south to the Inland Empire, I spent the impressionable ages of eight to thirteen in Clovis, California, adjacent to Fresno in the central region of the state. My neighborhood and school were a shift from the all-Black environments my parents experienced growing up. My father, Lucky, attended boarding school outside of Benin City, Nigeria, where he was born; my mother, Angela, was born and raised in 1960s South Central Los Angeles in an upper middle-class neighborhood where Etta James lived just down the street.

In their own way, my parents laid powerful foundations for my personal and bi-cultural identities, intending that I could lean on that knowledge as a source of deep pride. Angela, a journalist-turned-media relations expert never missed an opportunity to reframe a biased news headline or put in context the wildly restrictive immigration laws emerging from 1990s state politics. She taught me about the civil rights movement and how a child should be able to drink from any water fountain; she explained in approachable but frank terms how and why Jim Crow worked. Lucky asserted his Edo culture with custom heritage apparel tailored for the family. He hosted parties for Nigerian friends in the area where I heard him speak his native tongue and pidgin, and endless trays of potluck egusi stew, jollof, sweet plantain, crowded the kitchen counter. My father played and quoted so much Bob Marley, I may have been nearing high school before I understood that the legendary musician was, in fact, Jamaican and not Nigerian. It’s from these listening sessions that I learned about figures like Haile Selassie and Marcus Garvey and Pan-African ideas of freedom.

Over the past few years, Juneteenth has gained national recognition while school discussion of America’s history with Blackness is met with restriction. I find myself like many others, in a unique moment of reflection. What does it mean to bring forward a tradition that was not previously mine in practice, but absolutely belongs to me in the cultural realm as a Black American? Everywhere I look, I see delayed or disappeared justice for Black folks in this country. In the face of bewildering inequity from how police enforce laws, to whose homes get appropriately appraised, I know that my ability to experience, freely express, and maintain joy as a Black American is and will always be a political and powerful act. I have incorporated Juneteenth in my life as an adult, and I am moved by the complexity of the holiday as both a victory and an acknowledgment of loss. I love the symbolism of defiant joy, the willingness to cherish family and friends amid delicious food and drink.

I’ve been living in New York City since the beginning of 2020 and working on a book that reflects on American restaurant and dining culture. I’ve come across the Schomburg Center’s menu collection, a primary resource of historic restaurant and private dining menus spanning more than one hundred years. For the OA, I dove into these celebratory menus as inspiration for a fictional meal I might prepare one day—even outside the container of Juneteenth. I lingered on certain dishes because they sounded delicious, or because I liked the circuitous path of research I was led down by following the menu and its diners’ connections with one another. Each dish, each menu compilation, its own slice of history showing with whom and how Black folks spent their leisure social time and expanding our often-limited notions of what Black folks of days past ate and how those foods were prepared. I like the idea of mimicking small and potent past acts of happiness and delight in my own imaginary modern celebration of Black joy and liberation. So as we say, where the food at?

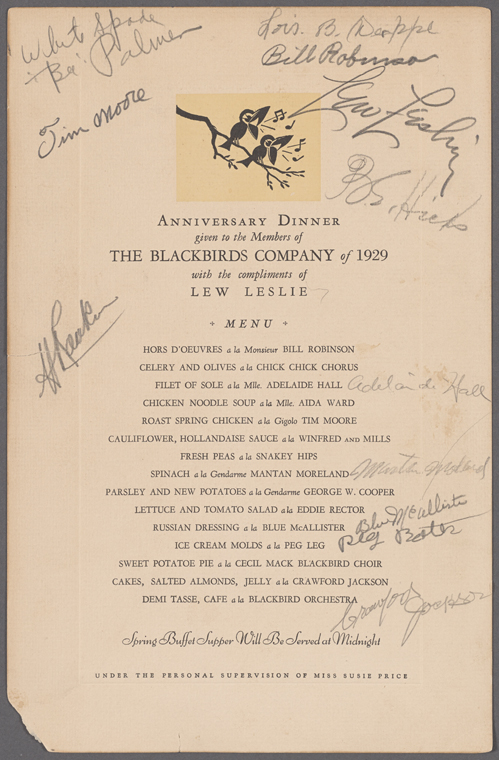

"Anniversary Dinner Given to the Members of the Blackbirds Company," courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library/Digital Collections.

Fresh peas from Black Broadway

In 1928, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson starred on Broadway in Blackbirds of 1928, a musical revue featuring an all-Black cast. After initial subpar reviews, Lew Leslie, a white vaudeville performer-turned Broadway writer and creator of the show, added new sections, including one solo number for Bojangles. In “Doin the New Low Down,” Bojangles sings and dances on a stairway as his main set piece. Bojangles did not receive wide recognition as the iconic performer he was until well into his middle age. His contributions to Blackbirds quickly became a hallmark of the show, with ticket sales tripling in number after his routine was added. The Afro American cited the musical as a “sensation,” and it was considered a highly successful Black production of the era, running for more than five hundred performances. The following year, Leslie hosted an anniversary dinner for the ensemble, attributing each of the fifteen dishes offered to a different cast member. A vague reference to hors d’oeuvres opens the meal, credited as “à la Monsieur Bill Robinson.” Course three, the filet of sole went to the well-known performer Mademoiselle Adelaide Hall, who was contemporary of Lena Horne, Ethel Waters, and Josephine Baker. She is perhaps best known for her singing accompaniment on 1927’s “Creole Love Call” by the great Duke Ellington.

The dinner features a roasted spring chicken, cauliflower in hollandaise, parsley with new potatoes, and closes with cakes, ice cream, and sweet potato pie. My favorite listing is the fresh peas for Snakey Hips, I think because I like the way it sounds: fresh peas à la Snakey Hips, like a directive for having a good time. Earl Snakehips Tucker was renowned for his gliding, writhing moves that were both elegant and sensual. He was a sensation on the Harlem club circuit. Among my less enchanting childhood food memories is eating frozen vegetables, steamed then salted as a default side at dinner. That medley of crimped carrot discs, corn, and nearly mushy peas was enough to turn me off the trifecta for years. Not until I lived in Atlanta as an adult and was introduced to the range of southern seasonal produce, did I understand that peas could have bite and inherent flavor. I like to imagine the peas in Snakehip’s honor taste as vibrant as his name sounds.

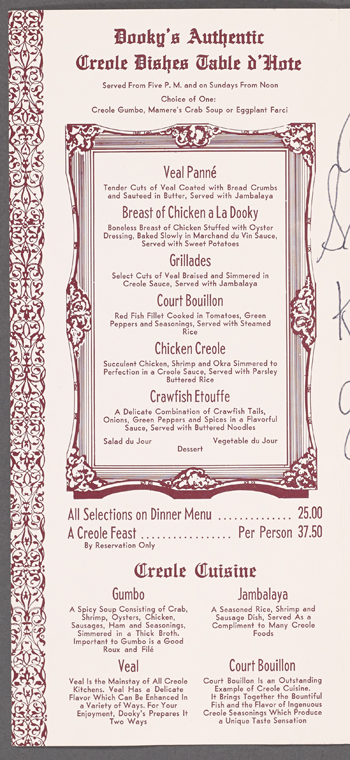

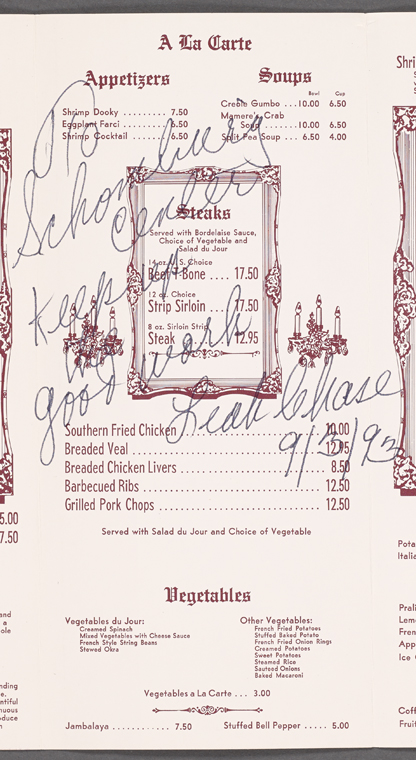

Chef Leah Chase’s jambalaya

I’ve been visiting New Orleans regularly since 2004 and the city gets harder for me to leave each time, thanks to ever deepening friendships, an ease to the daily routine that’s rare to experience elsewhere in the United States, and my love for the Black folks whose culinary and musical contributions make the city so soulful, sensory-rich, and dynamic.

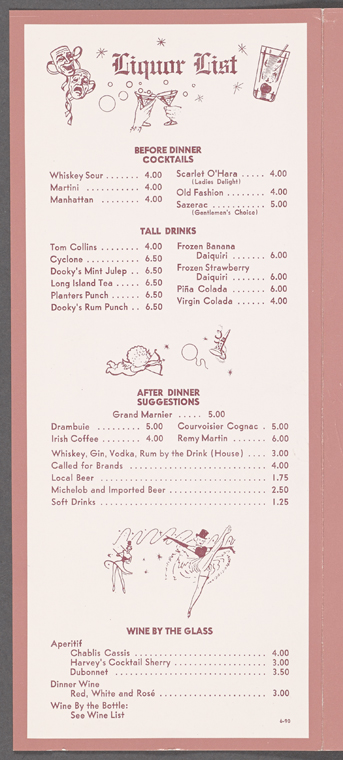

Dooky Chase’s restaurant in Tremé continues to serave its community as it did since the 1940s, as ownership has shifted to the children and grandchildren of Leah and Dooky Chase. A 1993 menu is a master class in Creole cooking, presenting flavorful, comforting dishes like crawfish etouffee, redfish poached in a court bouillon sauce, breaded veal, stuffed lobster, and gumbo (of course). Praline pudding and lemon meringue pie for dessert, mint juleps, rum punch, and frozen banana daiquiris on the drinks menu.

Mrs. Chase’s looping cursive scrawl across the center of the menu looks just like my grandmother Ruth’s, who was born one year later and just over one hundred miles east in Laurel, Mississippi. Grandma Ruth used to tell me how in school, teachers would restrict her from using her left hand to write, forcing her to become right-handed in matters of penmanship only. It’s impossible for me to not think of my grandmother when remembering Mrs. Chase, who I’d met on multiple occasions and with whom I had the opportunity to enjoy an uninterrupted, leisurely interview about her life and career as chef and proprietor of her family’s iconic restaurant while writing The Rise, the cookbook celebrating Black foodways that I wrote with Marcus Samuelsson. Mrs. Chase was a pioneer whose groundbreaking activism and talents won the admiration of presidents, entertainers, and pointedly, countless everyday diners. My grandmother was a pioneer in her career becoming the first Black woman on California’s parole board, then becoming the first woman and Black person to lead the state’s corrections department. They shared similar turns of phrase and were both kind women who were capable at issuing directives. I remember Mrs. Chase’s hands. They were working hands, and by that time, somewhat arthritic, and larger than one might expect for such a petite woman. “I point more now,” she once said laughing, of being in her mid-nineties in Dooky’s humming kitchen.

I love her jambalaya, which like gumbo, has countless interpretations. For me, Mrs. Chase’s is definitive and reflects the classic flavors of NOLA: a not too dry, not too soupy steaming hot pot of rice, smoked and hot sausages, shrimp, spices, and aromatics.

B. Smith decadence

I never had the chance to dine at B. Smith’s eponymous restaurant on E. 46th Street in Manhattan’s theater district, nor did I come up watching her weekly syndicated lifestyle show, “B. Smith with Style,” which began airing in the late '90s. But it was impossible to not encounter some aspect of Smith’s repertoire, vast as it was: during her eclectic career she wrote three cookbooks, published a magazine, had houseware and furniture collaborations, and three restaurants.

Born Barbara Elaine Smith in 1949, she parlayed a run with the traveling show Ebony Fashion Fair into a trailblazing modeling career, during which time she shortened her name. In 1976, she became only the second Black woman to feature on the cover of Mademoiselle. In the 1980s, she worked as a restaurant host and manager at America, a restaurant by Union Square Park. That relationship helped her establish B. Smith in 1986, followed by two locations in Washington, D.C.’s Union Station, and Sag Harbor. The Manhattan restaurant closed after 28 years, amid Smith’s ongoing struggles with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. She died in 2020 at 70 years old.

Smith was the epitome of elegance, breezily gliding in front of the camera with grace. She’d seamlessly offer advice for entertaining, ways to “jazz up” home décor, and demo recipes with stars like Mary Wilson from the Supremes, but always with a tenderness and relatability. Smith’s style was defined by beauty, color, vitality, and a warmth that seemed to exude from the screen and her restaurants were no less welcoming. They were celebrated as places to gather in distinguished circles, particularly among Black New Yorkers. Dishes from an archived restaurant menu sound inviting and familiar: grilled duck breast with endives and raspberry vinaigrette, pan-fried crab cake in a chile mayo, or a ginger-citrus swordfish with soy couscous.

I’m drawn to her dessert menu featuring coconut tuiles with white chocolate ice cream and macadamia nuts, a triple chocolate tarte in a fresh fruit coulis and crème anglaise, and perhaps what I’d be likely to order and prepare myself, the roasted pineapple doused in a coconut rum sauce and tropical fruit sorbet. Black joy may indeed be a political act but that doesn’t mean it’s itself the point. I love that Smith showed up in her work as herself, allowing the way she lived to define what she gave the world, rather than the other way around. Her accomplishments are among the most poignant sequels to the history marker of Juneteenth, where a Black woman’s freedom to express herself and celebrate life on her terms shimmers with brilliance, contributes to her community and beyond, and inspires generations. Perhaps Smith’s is only one example of a certain type of hard-won victory, but it is a bright and shining one I’m grateful to know of.

This series was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.